Part I of III in a series on Slavs and Tatars‘ Friendship of Nations: Polish Shi’ite Showbiz– a multiplatform exhibition, lecture-performance, and publication looking at the unlikely shared story of Poland and Iran. The exhibition opens at REDCAT gallery at the Roy and Edna Disney Theater/Cal Arts in Los Angeles on February 9th and runs through March 24th, 2013 before moving to Vancouver’s Presentation House from April 13th to May 26th, 2013. For more from Slavs and Tatars, check out Part II.

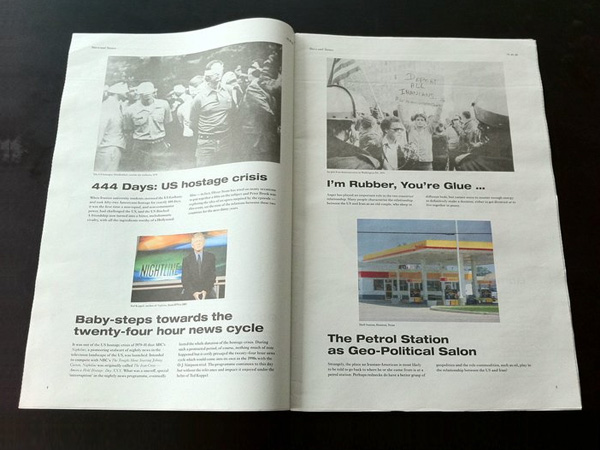

The eponymous book– with commissioned essays by the likes of Shiva Balaghi and Michael Kennedy, an interview between Adam Michnik and Ramin Jahanbegloo, and an archive by Slavs and Tatars, amongst others– will be co-published by London-based Book Works and the Sharjah Art Foundation in late February and launched at Art Dubai in mid-March.

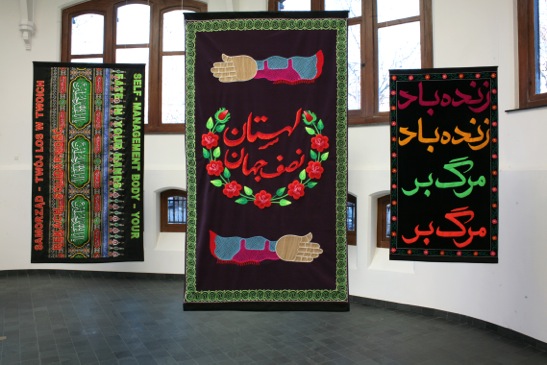

“Again, a Time Machine,” Eastside Projects, Birmingham.

Our interest in the improbable affinities of Poland and Iran began rather innocently, if cryptically, some four years ago. In a missive from Berlin, the periodical 032c asked us to think about two key dates—1979 and 1989—in anticipation of the planned celebrations marking the twentieth anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall. Given our severe case of bibliophilia–not to mention humble beginnings as a book-club (Oprah meets Attila the Hun if you will)–we took the two calendar years as book-ends to the two major geopolitical narratives of the 20th and 21st centuries: namely, Communism and political Islam.

Photo courtesy of Yana Foque / Kiosk, Ghent.

While the former Warsaw Pact countries—from East Germany to the Czech Republic, Hungary to Poland—had belatedly ripped a page from Reagan’s playbook, each trying to take credit for the downfall of Communism in Europe’s own backyard, the fireworks marking the thirtieth anniversary of the Iranian revolution were more muddied. Like a homeopathic supplement, the Islamic Republic of Iran’s impending crisis of direction was released in 2009 with a considerable delay, after a startling revolution, a near decade-long war of attrition with Iraq, a period of relative thaw followed by this belated, divisive and demagogic attempt to reinvigorate the original promises of the revolution.

As we researched these two modern moments—the 1979 Iranian Revolution and Poland’s Solidarność—the contested 2009 presidential elections in Iran swept out from under the proverbial Persian rug the limits of political Islam, just as the rest of the Arab world prepared to rise up and begin test-driving their own version.

After months of popular protest that led to a government crackdown, many in the reform movement, in particular the Green Movement, began to look to Eastern Europe–and in particular Poland–during the 1980’s as a successful precedent for nonviolent civil disobedience. Polish authors and thinkers hitherto unavailable in Persian–like Czesław Miłosz, Zygmunt Bauman, Łeszek Kołakowski– were being translated with a particular urgency unique to those determined in Iran to find a historical precedent in these slippery stakes of self-determination.

To paraphrase Zhou Enlai, who when asked by Nixon about the French Revolution replied, “It’s too soon to say.” The same could be said about delivering a definitive judgment on the 1979 Iranian Revolution. Our decision to focus primarily on the case study of Poland in 1989 though seems less polemical. Poland’s non-confrontational, slow burn of a strike movement Solidarność maintained momentum throughout the 1980s without the blood-letting witnessed in 1956 Budapest in or 1968 Prague. Whether it’s the political stagnation that slinks forward today in Iran or the baby steps being made by civil society across certain countries of the Arab spring, the Polish mix of methodical, behind-the-scenes non-violent disobedience, the instrumentalization of faith as a progressive force, and a deft if delicate use of compromise remains as relevant today as at any point in the past half century.

Our book-ends face outwards, though, back-to-back like contrarian curmudgeons. Pushing not against an existing series of volumes or a particular body of knowledge but rather pointing towards an empty shelf, hinting at a collection of tomes still to be written. For while 1989 spelled the end of the Cold War and Communism’s ostensible challenge to Western liberal democracy, 1979 marked the beginning of the next—perhaps successor—historical narrative in the shape of political Islam.

The approximation of these two narratives, though perhaps at first glance counter-intuitive, is not only a fixation of Slavs and Tatars. In fact, the list of scholars trying to bridge these two ideologies is a storied one. Through the figure of Abu Dharr, the first Islamic socialist and companion of the Prophet, Ali Shariati’s deft mix of Marxism and Shi’a Islam provided intellectual force in the early days of the Iranian Revolution#; Norman O. Brown, the University of California, Santa Cruz Professor, scholar of Blake and Joyce, considered Islam and Marxism…“two kinds of social criticism alive in the world today. Two still-revolutionary forces. Two tired old revolutionary horses”; French professor of political science Olivier Roy draws a convincing correspondence between the increasing attraction today of political Islam on one hand and on the other the collapse of traditional left-wing ideologies and labor movements in the last two decades.

In a historiographic version of Whac-a-Mole, our comparative look at the Iranian Revolution and Solidarność revealed several unexpected episodes of common heritage and cultural affinities. These include the exodus of 200,000 Polish refugees from Siberia and Kazakhstan to Iran during World War II as told in Khosrow Sinai’s touching documentary The Lost Requiem or the curious case of 16-17th century Sarmatism, when the Polish nobility believed itself to be descendants of a long-lost Iranic tribe from the Black Sea.

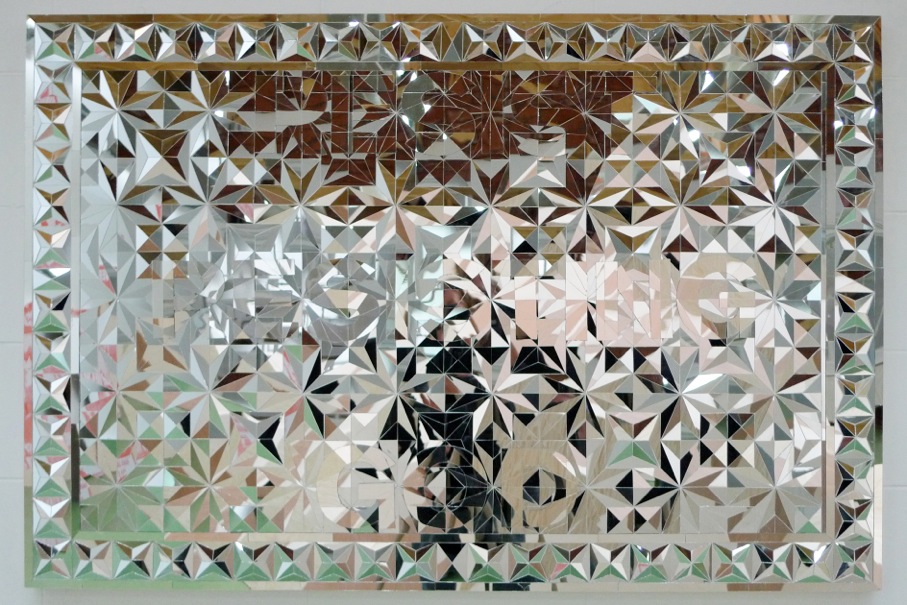

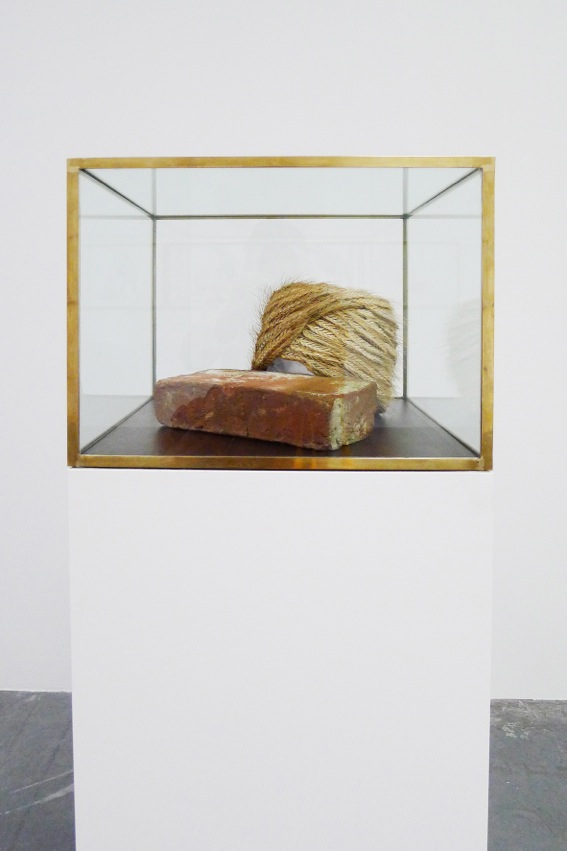

In addition to describing these episodes, we prescribe some too, in different iterations of the Friendship of Nations: Polish Shi’ite Showbiz cycle of work: from a balloon (Monobrow Manifesto) to a pamphlet, mirror-mosaics (Resist Resisting God) or performative-lecture (79.89.09). Seeking to rescue the old Soviet notion of дружба народов (literally “friendship between peoples or fraternity of peoples”) from its former, cynical self, we turned to the craft traditions common to both Poland and Iran–including reverse glass painting and textile banners used in Catholic processions and Shi’a Muharram ceremonies, respectively–to share the best practices of one country’s slow and steady experiences of resistance and religion with another.

An almost mirthful generosity occupied the courtyard of the heritage house at the 10th Sharjah Biennial where Friendship of Nations: Polish Shi’ite Showbiz was first exhibited. From the very early days of installation, local Baluchis, Afghans, and Iraqis would stop by, sit down, converse with us or amongst themselves, and seek shade from the scorching sun, courtesy of while sipping orange blossom-infused tea and eating dried mulberries. Adjacent to the only Shi’ite mosque in Sharjah, Friendship of Nations acted as the cheerful younger brother to its more indulgent, if edified, blue tiled elder sibling across the road.

By articulating a space of political discourse shaped first and foremost by the codes of hospitality, in Sharjah, Friendship of Nations became a de-facto rest-stop, a meeting point, all the more acute in a biennial taking place under sweltering temperatures nearing 30ºC. But heat is often more than mere meteorology: both the immediate and greater context within which the exhibition took place point to the urgent need to rethink the very delivery, if not posture and conception of critique itself. Friendship of Nations, due to its location, was sandwiched between the censored contribution that sparked the controversial dismissal of the Foundation’s director on one end and the only Shi’a mosque in Sharjah on the other.

The biennial opened, after all, on the same day that the UAE and Saudi Arabia, two Sunni countries, sent troops into neighboring Bahrain, an island kingdom with a majority Shi’ite population. That a project addressing self-determination and the translation of civil disobedience from Eastern Europe to the Middle East, amidst the early days of the Arab Spring, within this curated context, did not cause controversy is a testament to the oft-overlooked seduction of generosity which asks us to commemorate as much as condemn, to critique with a smile as wide as the analysis itself, and to joy through mourning.

–

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Slavs and Tatars is a faction of polemics and intimacies devoted to an area east of the former Berlin Wall and west of the Great Wall of China known as Eurasia. The collective’s work spans several media, disciplines, and a broad spectrum of cultural registers (high and low) focusing on an oft-forgotten sphere of influence between Slavs, Caucasians and Central Asians. Slavs and Tatars has published Kidnapping Mountains (Book Works, 2009), Love Me, Love Me Not: Changed Names (onestar press, 2010) ), Not Moscow Not Mecca (Revolver/Secession, 2012), Khhhhhhh (Mousse/Moravia Gallery, 2012) as well as their translation of the legendary Azeri satire Molla Nasreddin: the magazine that would’ve, could’ve, should’ve (JRP-Ringier, 2011). Their work has been exhibited at the Frieze Sculpture Park, the 10th Sharjah, 8th Mercosul, 3rd Thessaloniki, and 9th Gwangju Biennials.

After devoting the past 5 years primarily to two cycles of work, namely, a celebration of complexity in the Caucasus (Kidnapping Mountains, Molla Nasreddin, Hymns of No Resistance) and the unlikely heritage between Poland and Iran (Friendship of Nations: Polish Shi’ite Showbiz, 79.89.09), Slavs and Tatars have begun work on their third cycle, The Faculty of Substitution, on mystical protest and the revolutionary role of the sacred and syncretic, for group exhibitions at the GfZK, Leipzig and the New Museum Triennial as well as recent solo engagements at Secession, Vienna (Not Moscow Not Mecca), MoMA, NY (Beyonsense), and Moravia Gallery, Brno (Khhhhhhh). Their 2013 engagements include, among others, a solo exhibition at Künstlerhaus Stuttgart and group exhibitions at the Centre Pompidou and Kunsthalle Wien.

5 comments

Reblogged this on RD Revilo.