This article is by a guest contributor, Sina Zekavat. Sina has lived in three paradoxical and yet similar cities: Tehran, London and New York. His research interests and inspiration lie somewhere between architecture without architects, critical geography, informal urbanism and the right to the city movements. All photographs were taken by the author unless otherwise stated.

It is impossible to walk around Yerevan today and not notice the melancholic presence of one building typology across this rapidly changing urban landscape: The Soviet social housing block. Far from being a clean break from the past, the Soviet housing legacy remains highly present and influential in the daily experience of Yerevan. These grey and often crumbling buildings constitute the largest share of housing in Armenia. Unlike some countries with longer capitalist heritages where social housing has become marginalized as a place for the poor, in Yerevan and in many other post-socialist Eurasian cities like Baku, Tbilisi and Tashkent, these housing blocks still provide the most common and accessible living conditions for average citizens.

Through careful observation of Yerevan’s Soviet housing legacy as well as Yerevan’s current transformations this article aims to explore the slow decay of socialism as a complex and multilayered process that symbolizes not simply the death of a particular utopia or ideology but also the emergence of new, and often conflicting, notions of belonging and nationhood.

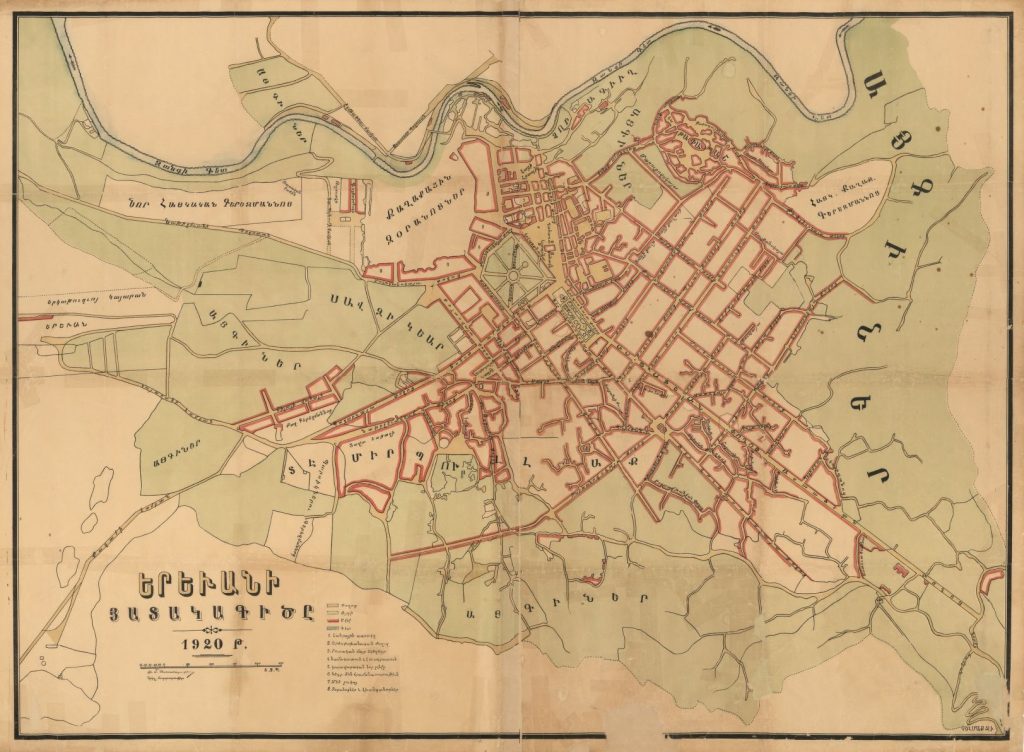

Yerevan is the capital and the largest city of Armenia. With a population of 1.117 million, it contains approximately 34% of the total population and 54% of the urban population of Armenia. The city’s origin dates back to the 8th century BC when settlements started to grow along the banks of Hrazdan River at the northeast of the Ararat plain. Years of political transformation, domination, invasion and war between Arab, Persian, Ottoman and Russian rulers have left little physical trace of the early history of this city. Each empire shaped Yerevan to satisfy its own ideological identity. Yet, the year 1920 marked an important chapter of Yerevan’s ongoing urban history– when the city became the capital of the Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic, one of the fifteen republics of the Soviet Union.

Soviet Urbanization

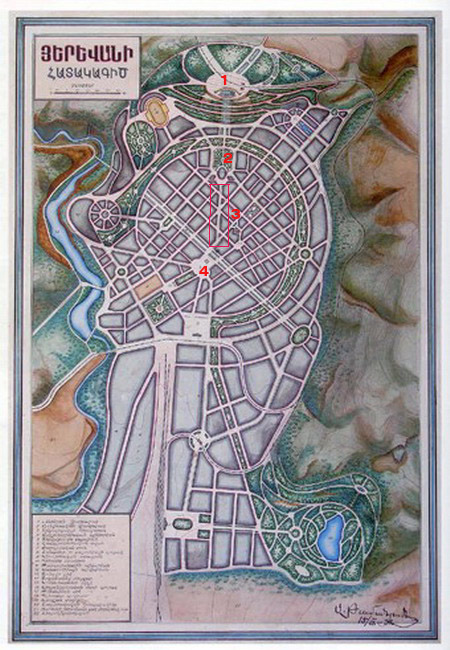

The first general plan of Yerevan under Soviet rule was approved in 1924 and was developed by the Russian-born Armenian architect Alexander Tamanian. Inspired by the Garden City trends of its time, the radial plan was designed to accommodate a population of 150,000 and was overlaid on the existing city structure. Most parts of the existing urban fabric were incorporated into the new plan. But not all. Due to the Soviets’ early internationalist ideological approach to religion and history, many buildings didn’t survive this major transformation and consequently hundreds of houses and historic buildings including churches, mosques, baths, bazaars, caravanserais as well as the old Erivan fortress were demolished. Similar to other socialist cities, an ideal combination of economic and labor efficiency, social justice in terms of access to urban goods and services, and a high quality of communal life for the urban populations were typical visions for urban Yerevan.

Rapid industrialization catalyzed the mass migration of people from rural areas to Yerevan. State-owned housing grew rapidly, and urbanization became an important tool for the socialist government to engineer and organize the flowing population into a unified workforce.

After the death of Joseph Stalin in 1953 — and from the early 1960’s until the collapse of the Soviet state in 1991 — urbanization continued on a faster pace and was based on modified ideologies. Rationalism, functionalism and mass production were set to replace “wasteful” ornament and monumental plannings of the Stalin era. Architects were ordered to focus on simple and reproducible design, low cost and increased construction speed. Concrete prefabrication and modular systems of construction are notable outcomes of such changes.

Khrushchev’s relative ease of social and cultural limitations allowed some level of openness for the revival of Armenian nationalism and the strategic reframing of diaspora as the integral part of Armenian national identity. The 1960’s repatriation of Armenians as well as the increasing rural-urban migrations resulted in an increasing shortage of dwellings in Armenia and more notably in Yerevan. Despite Khrushchev’s mass housing campaign, the shortage of dwellings continued until the 80’s and reached its peak in 1988 after the mass displacements caused by the Nagorno-Karabakh ethnic conflict with Azerbaijan, followed by the devastating earthquake of 1988.

Place-Making through Spatial Appropriation

An important and yet overlooked aspect of Armenian urban history is the domestication of state-owned spaces, resulting from direct acts of place-making and the appropriation of physical space.

Throughout decades of addition, expansion and ad hoc interior remodeling, many Armenians transformed their state-owned prefabricated houses into distinct domestic spaces. This was a spontaneous response to the spatial shortcomings of such spaces in accommodating rural and patrilocal lifestyles. The Soviet state’s consistent promotion and enforcement of the nuclear family as an ideal form of social organization was one of the main guidelines for architectural design. In fact, through carefully designed architecture, the Soviet state planned to dismantle the multigenerational and patrilocal ties that Armenian families had greatly developed and relied on prior to their migration from rural areas. This means that for the urban planners and architects in Moscow, modular design was not merely a means for faster construction but also a tool for creating a homogeneous urban society of smaller family units.

Many family ties were broken but not all Armenian families played their prescribed role as passive inhabitants of these spaces. By enclosing exterior balconies and removing inner partition walls, families would add extra floor area to their houses and would create alternative spatial arrangements. The enclosed balconies would usually become bedrooms for children or young married couples. There are accounts that interior spaces changed almost with every birth, death and marriage in order to adjust to the changing family structures. Most sleeping spaces had no permanent function or layout since they were converted into shared spaces by day.

While many Western and Soviet sources have argued that extended family traditions had been diminished under Soviet policies, the continuity of such spatial transformations shows that ideologies of traditional kinship have played an active and central role in Yerevan’s transformation until today. In fact, patterns of intense interdependence among relatives and neighbors resulted in less definable boundaries between kinship and neighborship.

Becoming a Global City: Inventing Hierarchy

With the collapse of the Soviet Union, Yerevan became the capital of the independent Republic of Armenia in 1991. Since gaining independence, the capital city has been subjected to a complex process of postcolonial nation-building while simultaneously adopting globalized urbanization trends. Implementation of social, economic and spatial hierarchies has become the necessary first step for introducing the city to global markets. Spaces of new Armenianness are carved out of the existing socialist urban fabric. Similar to many other gentrifying cities, demolition and displacement are becoming more and more a common practice. New multinational construction projects are presented and justified as acts of nation-building while the low income majority is expected by the emerging elite to make sacrifices for the benefit of the nation as a whole.

The construction of Northern Avenue is one of the recent examples of this conflicting process. The project was envisioned by city architect Tamanian in mid 1900s as an axis connecting the Mother Armenia statue (former Stalin statue), the opera house and the Republic square (former Lenin square) (Refer to Map 2). But the plan was only implemented in early 2000 when city officials saw the transformative potential of the project. Standing in the project’s way, hundreds of low-income houses were bought and demolished. Plots of land were consolidated into larger lots and eventually auctioned to private Russian-Armenian developers in order to make way for a new luxury residential-commercial mix use territory.

Right image: Same view in 2013 after the opening of Northern Avenue. Image credit: Hayk Bianjyan

While the officials present the project as a “new image” for the city offering hundreds of houses and commercial spaces, the displaced residents continue to storm governmental offices arguing that what the government had paid them is not enough for purchasing a new house with the same amenities in any part of the city.

It is during these processes of globalization that the old center-periphery orders are replaced by more complex forms of socio-spatial hierarchies. In other words, the old, decrepit, anti-modern center is being remade to be the “tradition-based national” yet global and cosmopolitan heart of the city, while Soviet apartment blocks, previously the harbingers of modernity, are now relegated not only to the geographic but also the mental periphery. For the displaced residents, street vendors, and owners of small shops, the periphery is now a new everyday socio-spatial reality that was arguably unimaginable in the Soviet days.

It is important to mention that the idealized diasporic visions of Yerevan as a home city also play a critical role in the emergence of such development projects. For example, every year the Los Angeles based not-for-profit organization, Hayastan All Armenian Fund, solicits millions of dollars of diaspora donation for developments inside Armenia. In a video from the organization’s 2013 telethon, Northern Avenue buildings represent a new Armenia while groups of Armenian youth run between these buildings expressing with joy their hope and optimism.

Dialogue with the past?

The mass-produced housings of the Soviet era resemble not only a unique chapter of Armenia’s urban history but also the collective memories and cultural aesthetics of a recent past that are struggling to be recognized and to be integrated into the country’s overall transformation.

Harch Bayadyan, Armenian cultural critic and professor of Media and Cultural Studies in Yerevan State University, has written extensively on the complexities of postcolonial and national transition in the context of Armenian aesthetics and collective identity. Calling for “the need for dialogue with the Soviet past” Bayadyan has been critical of the new government’s social and economic plans from education to urbanization as having no resemblance and connection to Armenia’s historical experiences.

From Soviet housing blocks to upmarket mixed-use developments of the new Armenian government, state formulated narratives of modernity, globality, citizenship and nationhood continue finding ever changing forms in Yerevan’s built environment. With the increasing fetishization of “development equals progress” mentality, what is unfolding today is the flattening of cultural imaginations as well as the possible futures of Yerevan as a richly diverse and complex metropolis of multiple histories that could house all Armenians regardless of their social and economic status.

References:

Altering States: Ethnographies of Transition in Eastern Europe and the Former Soviet Union (2000). Edited by Daphne Berdahl, Matti Bunzl, Martha Lampland. University of Michigan Press

Urban Spaces After Socialism: Ethnographies of Public Places in Eurasian Cities (2011). Edited by Tsypylma Darieva, Wolfgang Kaschuba, and Melanie Krebs. Frankfurt/ Main Campus.

10 comments

This article is absolutely wonderful! Fascinating and necessary read, I wish more people would pay greater attention to the social, cultural and economic implications of the shifting architectural landscape in this city. It’s perhaps the most obvious indicator of the city’s confused relationship with modernity.