This article is the third installment in a three-part series on oil, nostalgia, and the southwestern Iranian city of Abadan.The first part in the series can be found here and the second part can be found here.

The series is authored by Rasmus Christian Elling, an assistant professor at the University of Copenhagen where he teaches the sociology and modern history of Iran as well as urban theory. He has recently published a book on minorities, ethnicity and nationalism in Iran after Khomeini, and is now working on the history of Abadan. This series was originally published in Danish.

You can support Elling’s Internet campaign to fund future research and publications on Abadan here.

Part Three

I want to cry

in mourning the death of the harbor

My devastated harbor

burial of fluttering flowers

Oh Abadan, how it disappeared

under blood and fire and smoke

My devastated harbor

there used to be life in you

— ‘Abadan’, poem by Ardalan Sarfaraz.

As comforting as it may feel, nostalgia is contentious: any remembrance of the past rests on selective amnesia.

In a country where the state persistently asserts itself as the manifestation of the people’s will through revolution, longing for the pre-revolution past can be seen as a protest. Indeed, local accounts of Abadan can be at odds with official history in the Islamic Republic. But they are also often in conflict with each other.

These conflicting views on the past grow out of common soil. They are rooted in the contradictory experience of modernity that oil brought to Abadan. That experience includes war.

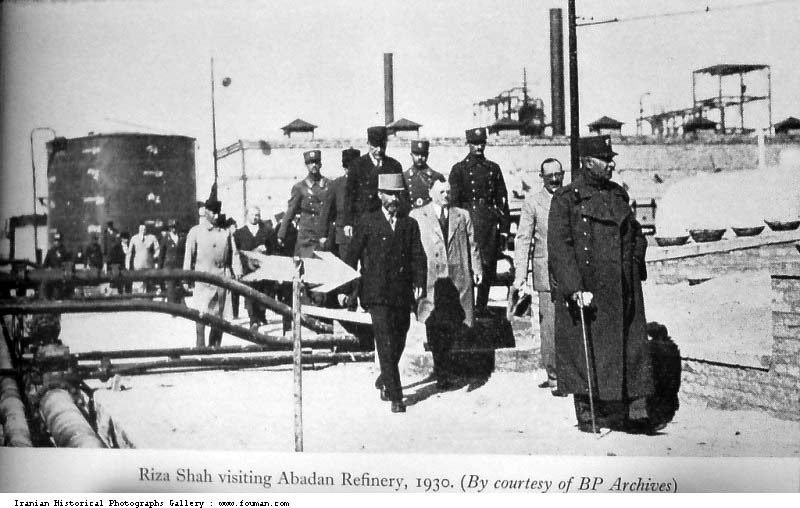

In 1913, the British navy — under Winston Churchill, also a Company lobbyist — shifted from coal to oil, which propelled Britain towards victory in World War I. As Abadan became a vital asset for the Empire, the Company acted as a military entity, controlling and coercing labor through policing and intelligence, and in times of unrest, employing local tribes or threatening with British intervention.

Yet Abadan’s oil workers quickly learned to pressure the Company by paralyzing that crucial part of the production cycle, the refinery. The 1929 oil refinery strike inspired a budding nationalist movement against foreign dominance across Iran. The demand for nationalization was publicly expressed for the first time. Oil had thus given birth to a new form of political agency, to class awareness and to anti-imperialist sentiments that would impact profoundly on Iran’s history.

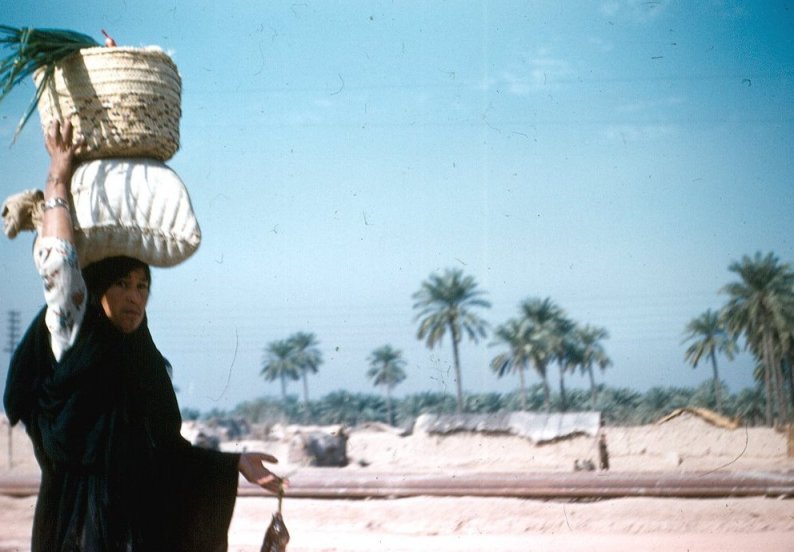

Faced with a growing labor movement in Abadan and a bolder Shah in Tehran, the Company had to make concessions. But higher wages, increased social mobility and more welfare was not enough to mask the basic unfairness of the Company earning huge profits from Iranian resources without even paying taxes to Iran. Terms such as junior and senior employee were mere euphemisms for the structural discrimination that shaped the work, community and daily life of oil workers.

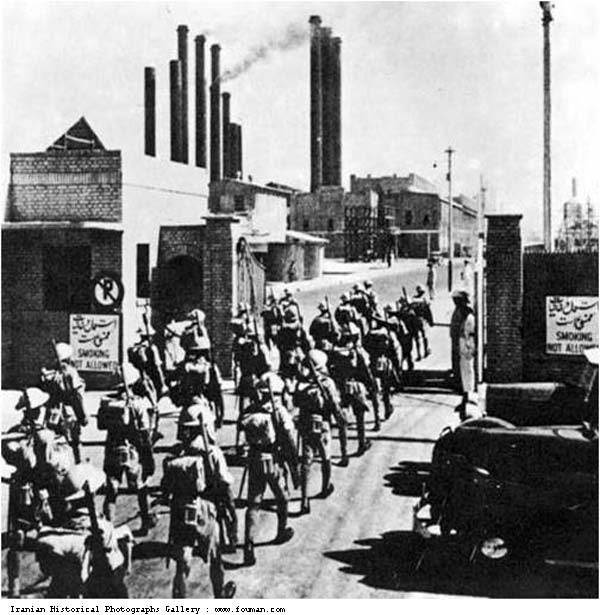

On the pretext of the Second World War, amidst hunger, chaos and British occupation of southern Iran, the Company managed to strengthen its hold on Abadan. But already in 1946, the labor movement rose again during a major strike. With the support of thousands of disgruntled workers, the Communist Tudeh Party took control over Abadan and the refinery. The British played disgruntled Arab tribes off against the strikers, and then forced the Iranian police to crack down on Communists.

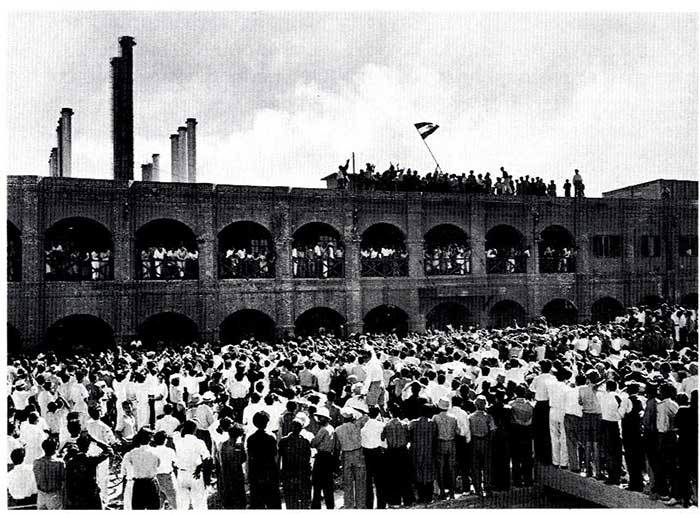

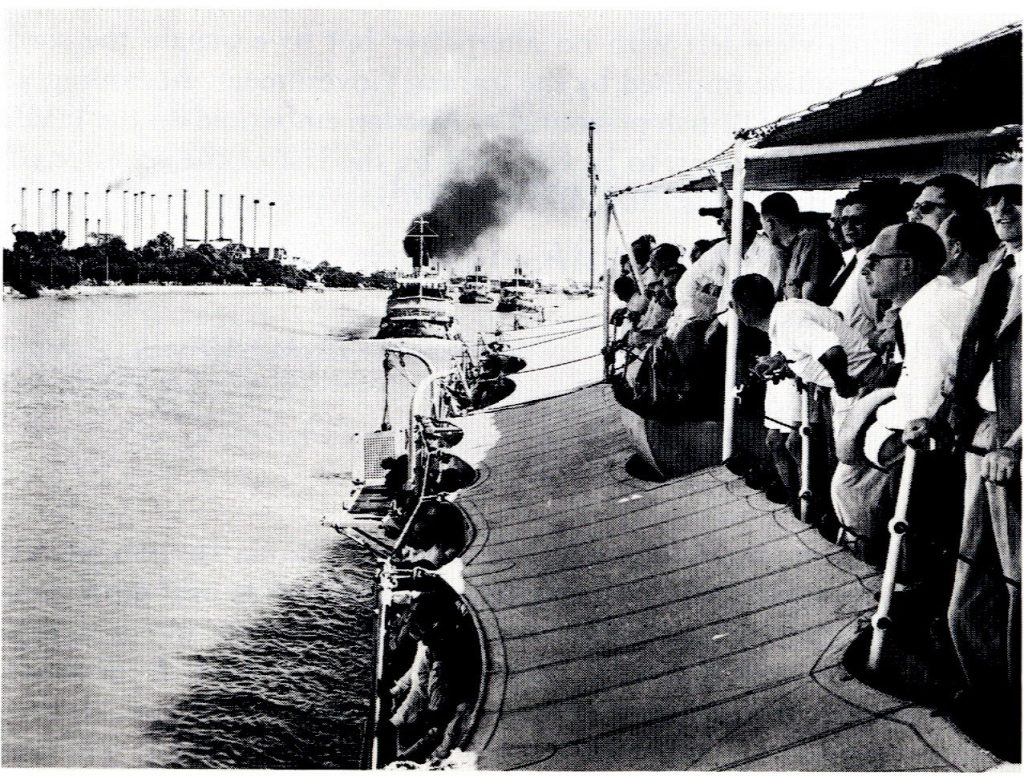

And yet, it was too late. In 1951, the democratic Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddeq, riding a wave of anti-imperialist sentiment, finally nationalized Iran’s oil. During the dramatic ‘Abadan Crisis,’ British employees were evacuated while oil workers hoisted the Iranian flag on the refinery.

Oil was now a symbol of independence and popular will. But in just two years, Mosaddeq was overthrown in a CIA-organized coup, which paved the way for an emboldened, more autocratic Shah.

While Iran now owned its oil, the country became dependent on US support. Rising oil revenues were spent to finance the Shah’s overambitious plans and megalomania.

”The Abadan Crisis” as portrayed on British television, 1951.

A turning point was an event in Abadan: on 19th August 1978, unknown perpetrators set fire to the fully packed Cinema Rex. At least 500 died in this, one of the biggest acts of terrorism before 9/11.

In the months after the fire, the movement against the Shah was radicalized, culminating in the revolution and the establishment of the Islamic Republic. The last foreigners left Abadan and the revolutionary state purged Iran of Western cultural imperialism and moral decadence.

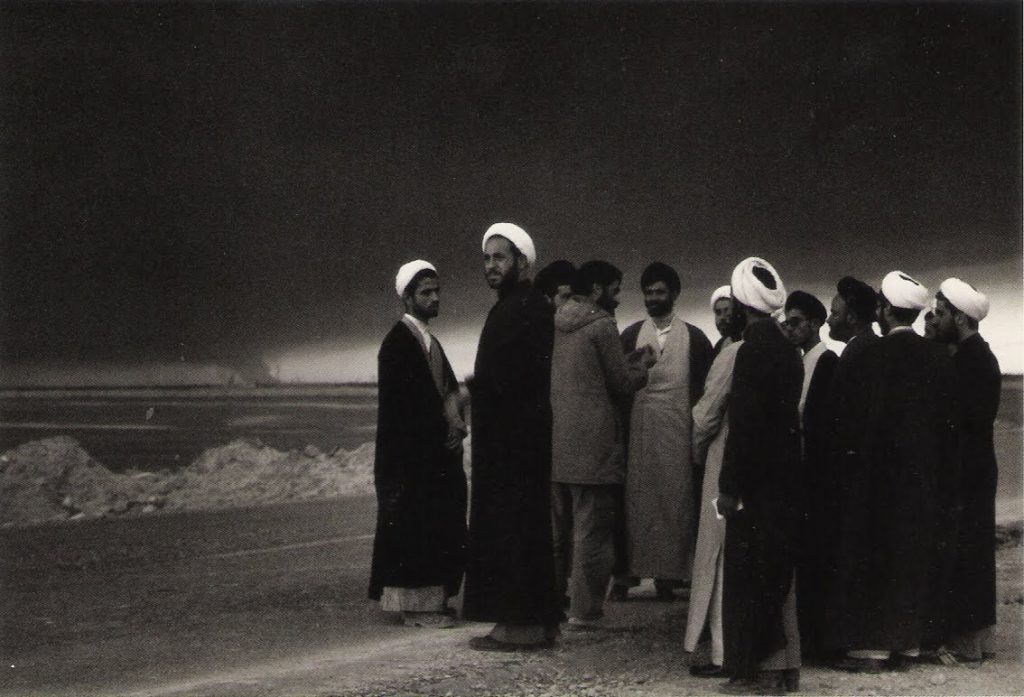

Just as Khomeini had consolidated his power, Iran was attacked in 1980: the Iraqi invasion was partly prompted by Saddam Hussein’s ambition of annexing Iran’s oil-rich region around Abadan. In some of the worst battles of the eight-year war, locals and volunteer soldiers gave the Iraqi invaders stiff resistance.

Just as Khomeini had consolidated his power, Iran was attacked in 1980: the Iraqi invasion was partly prompted by Saddam Hussein’s ambition of annexing Iran’s oil-rich region around Abadan. In some of the worst battles of the eight-year war, locals and volunteer soldiers gave the Iraqi invaders stiff resistance.

Abadan’s neighboring city of Khorramshahr was the scene of a brutal siege and, in 1982, a liberation considered epic in Iran today. Thousands died during the battles for Khorramshahr and Abadan, among them some of Iran’s most celebrated martyrs. Abadan was bombed and besieged for 18 months, and almost all inhabitants were evacuated and displaced.

Excerpt from the Iranian documentary ”Abadan, Oppressed City” on wartime Abadan.

Near the end of 1980s, Abadan was gradually resettled, although many never returned. In 1989, the refinery resumed operations, but only in 1997 could it reach its pre-war output. By that time, its place in the Iranian energy grid had been taken over by newer installations elsewhere. Attempts to revive the local economy have only been partly successful. The plans for a major free trade zone around Abadan and Khorramshahr appears in shambles, and Abadan is plagued by a host of socioeconomic problems.

As a juggernaut of modernity, oil heralded rapid development, profound change and a prospect of emancipation. It inspired movements, brought them to their knees and saw them rise again. Through oil, Iranians imagined a new era, liberated from imperialism and as masters in their own house. But ousting the British only gave way to the tyranny of the Shah, and freedom from the Shah was followed by the horror of war.

Although oil made many futures seem attainable, it never gave Abadan peace. Those living in Abadan today are still suffering from the consequences of war.

Oil, water and corroded promises

A key Abadani grievance is that the city has lost its vibrant, healthy and productive environment.

Almost a third of Abadan population subsists on financial support from the government, and Khuzestan officially has 27% unemployment. The local youth, I am told repeatedly during my visits to Abadan, is marked by disillusion, and some have slipped into drug abuse.

“The young don’t do sports anymore. We used to have the best sportsmen in the country, but now the riff-raff hangs around in the streets all night doing drugs,” I was told by an elderly Abadani gentleman working in a local bank. There are no statistics available, but an official tells me that Abadan is suffering from a “drug epidemic.”

The social environment seems to suffer in tandem with the physical environment.

In all of Khuzestan Province, water is of an alarmingly bad quality, particularly so around Abadan. The region is deeply affected by air pollution from metal, sugarcane and petrochemical industries. The provincial capital Ahwaz, 130 km. north of Abadan, has the dubious honor of being the most polluted of all cities in the world. Khuzestanis suffer from illnesses caused by the pollution, and drought, salinization, erosion, acid rain and mismanagement have destroyed much agriculture and nature. As rivers have been dammed and marshes drained in Iran, Iraq and Turkey, the region has become a huge dustbowl. Abadan is regularly smothered in sandstorms.

Popular notions of wellbeing and prosperity in Abadan are tied directly to water, and access to water, the quality of water and the symbolic power of water in a desert community are also key themes in the nostalgic books. The books often contain odes to the rivers that flow around Abadan, or pay homage to the drinking water systems, water purification plants and swimming pools constructed by the Company.

Not all of the books praise the charitable work of the Company, though.

The retired school teacher and now Karaj-based writer Ali Farrokhmehr has written eight books about his life in Abadan. In his Âbâdân: Khâk-e khubân, yâd-e yârân(‘Abadan: Soil of the Good, Memory of Friends’), we are told how in the late 1940s, the Company dug a canal from the Bahmanshir River into one of the new quarters, supplying water to gardens and a large public swimming pool. Farrokhmehr remembers playing in the pool as a child. But he also distances himself from the spectacle, which was in fact a PR strategy to cover up inequality:

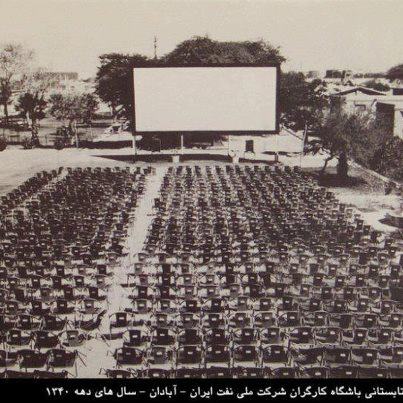

“All the Company neighborhoods had clean drinking water, electricity and asphalted streets but the rest of the city was barred from the bare necessities of life! Abadan was inextricably tied together with contradictions. Next to the biggest refinery in the world, misery thrived. A lump of ice was something you could only dream of! In the shade of the refinery, the only recreation for Lors, Kurds, Arabs, Baluchis and Persians was a pool and the Bahmanshir Cinema under open sky! The sum of all these contradictions made Abadan a city on the brink of explosion!”

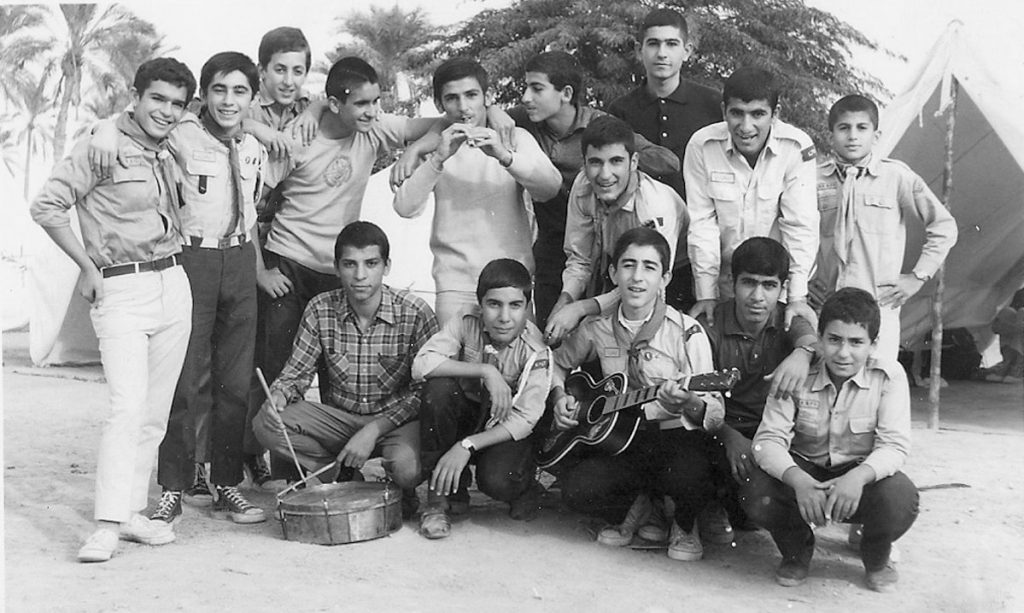

Farrokhmehr grew up in the shantytown, and has no rosy picture to paint of Abadan under the British or under the Shah. The aspect of Abadan’s past that he deems memorable is a culture, which may have taken shape in the spaces created by the Company, but was unmistakably Iranian, patriotic and religious: the Iranians who as booksellers, teachers, poets, sportsmen and engineers created Abadan.

Farrokhmehr’s Abadan is a city of the oppressed, devout, revolutionary and the martyrs: the stage for an epic struggle against the Western powers that sought to hamper Iran’s industrial and spiritual development. When Iranians succeeded in wrestling oil out of foreign hands, the imperialists took revenge by destroying the country with the help of their henchman, Saddam Hussein.

Farrokhmehr’s Abadan is a city of the oppressed, devout, revolutionary and the martyrs: the stage for an epic struggle against the Western powers that sought to hamper Iran’s industrial and spiritual development. When Iranians succeeded in wrestling oil out of foreign hands, the imperialists took revenge by destroying the country with the help of their henchman, Saddam Hussein.

Farrokhmehr denies that his longing glorifies the past:

“Why, with all these disappointments and all this pain do hearts still wheel and circle over the past? In every corner of Iran, the ageing and elderly bring the days of yore to life with a sigh. A sigh, not of resentment for the present, but because days are passing fleetingly, and life is short … Yes, it was indeed oil that turned ‘Abbâdân [the old Arabic name of the city] into Âbâdân [the present name, which connotes ‘progress’ and ‘blossoming’]. Yes, it was indeed the establishment of the refinery that made Abadan a city! The oil, the refinery, ArvandRud River, Bahmanshir River, the money, the harbor, the export and the import — they turned the island into a thriving port. In time, slowly, like a turtle. But with all those riches, it could also have blossomed more than it did!”

Farrokhmehr, then, is not nostalgic for the splendor of the past, but rather for the missed futures of the past: the city did not become what oil could have made it become.

In another book, Âbâdân, kuche-ye mehrabâni (‘Abadan, Street of Love’), his subtle critique of the post-revolution state surfaces:

“The long war, life as displaced and in exile, promises and assurances, neither war nor peace; and slowly, Abadan lost its value and dignity, and the population turned disillusioned and their hearts grew cold. The artificial lake and the swimming pool were forgotten. The water pipes in the ground corroded. The gardens faded and Tank One and Tank Two [neighborhoods in Abadan] became worse than shantytowns! … This is not just the story of water and drought. It is the story of a city being phased out.”

Part of Farrokhmehr’s story, then, is the frustration with unfulfilled promises of post-war reconstruction and the indifference of those in power. This echoes those in Iran’s lower classes who had hoped that the revolution would bring social justice and progress for all. It also echoes a frustration felt across Khuzestan, where infrastructure and homes are still marked by a war that ended 27 years ago.

But it is not just a story about frustration with the state.

Abadani nostalgia exposes the paradox of the modern: the disillusion of life in a city that is surrounded by rivers but does not even have clean drinking water; the disappointment of living so close to a resource that promised to transform life, and then, after liberation, the experience of being crushed by the war machine of covetous foreign powers.

As a symbol of injustice and unfulfilled promises, oil is present throughout the story of a city phased out.

Last scene: the amnesia of liberation

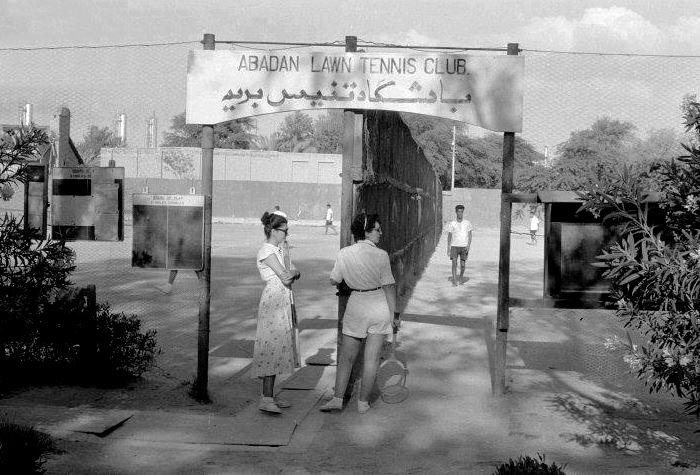

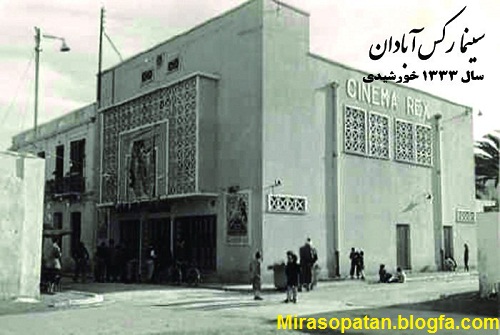

Cinemas stand out in the geography of memory sketched in the nostalgic books. They symbolize the windows to the world that oil opened up in Abadan.

Cinema has its own story that began in 1912 when the first portable projector was imported to entertain British employees exclusively. Soon, the Company realized the many benefits of films and opened cinemas, open air or in disused warehouses, and eventually new, grand cinema complexes. Here, the Company would screen propaganda news from England along with commercials for the Company or for products available in Company stores.

The Company even produced a film about Abadan, Persian Story. It was meant to convince an European audience of the magical power of oil, of the charity of the Company and of Abadan as a prime example of modern progress in even the most backward setting.

Excerpt from Persian Story.

From the 1930s, privately owned cinemas were also established, including some of the biggest and technically most advanced in the Middle East. They showed Western movies, and in the nostalgic books, Abadanis remember watching Tarzan, Hopalong Cassidy and East of Eden. Sometimes, they screened Indian Bollywood dramas or romantic movies from Egypt. Thanks to Abadan’s relative independence from Tehran’s censorship, Iranian films with social and political messages could be shown uncut. But gangster flicks and sordid comedies were always popular.

The cinemas drew people from all over the region to Abadan: Arab tribesmen came riding or sailing in just to watch Abdel Halim Hafez, the Dark-Skinned Nightingale from Cairo sing of his broken heart, or to watch Charlton Heston race for his life in Ben Hur.

A trip to the cinema could be a family picnic or a chance to steal a kiss. Cinemagoers would sing, cry and shout, and if the screening was interrupted by power cuts, riots could erupt. Abadan was obsessed with films. The many cinemas inspired some of Iran’s best directors, including Nasser Taghva’i and Nader Amiri. Cinemas were a physical landmark: one of the most popular postcards from old Abadan shows the magnificent Taj Cinema, built with imported redbrick.

But the remembrance of Abadan of the Cinemas also carries within it a need to forget: for many Abadanis, the last scene in the story of Abadan’s glory took place in the cinema.

That fateful, sweltering hot night of August 19, 1978, when more than 500 Abadanis perished in a blaze, the film Gavazn-hâ (‘The Deer’) had drawn a sold-out show to Cinema Rex. Today, it still appears significant that it was exactly this film that was showing.

Gavazn-hâ, a modern classic by Mas’ud Kimiai, tells the story of Qodrat, a bank robber on the run who takes refuge with his childhood friend, the junkie Seyyed, and his girlfriend who works in Tehran’s sleazy cabarets. With the help of Qodrat, Seyyed manages to quit his addiction, defend the honor of his girlfriend and resist his rivals. With its ruthless depiction of the downside of modernity, the film only barely slipped through censorship. It was received as a critique of Iranian society under the Shah.

It is also with this understanding that the Islamic Republic makes sense out of the fire: that the Shah wanted to scare people away from the simmering rebellion, to punish those watching critical movies, or to throw the blame on Islamic radicals when in fact it was the Shah’s own people who were behind. Another interpretation is that Islamists started the fire: blaming the Shah while targeting a cinema, which for some represented the epitome of sin, moral decay and Western decadence.

No matter what, the nostalgia for Abadan of the Cinemas is contrasted by the painful experience of modernity that went up into flames in the oil city: first in the Cinema Rex fire, and then, two years later, in the Iran-Iraq War. The final act in the combustible story of Abadan’s glory starts with a fire and ends with a war.

As opposed to the official narrative that treats the patriotic fight against Iraq as the starting point of a new golden era in Iran’s history, Abadan’s nostalgic books end with the war. This is obviously connected to the evacuation: memories and memoirs end with a tragic afterword of displacement, life in refugee camps, moving to other cities or leaving Iran altogether.

The war reset Abadan’s historic clock. It is as if those who are still in Abadan and writing about the city’s past are living in the fading setting of what used to be a glorious film that did not end as promised. Oil went from being a source of progress to the cause of enmity, destruction and dislocation; and now, the backdrop for stillness and inertia.

And yet oil continues to feed nostalgia, criticism and self-criticism, identity and pride.

When there is a power cut

“Our refinery used to be the biggest in the world, and it is still big. And yet we have power cuts! It simply doesn’t add up,” an interviewee tells me. And as a visitor, one does wonder how a city based on a refinery is not able to provide all citizens with a stable source of electricity.

Oil is a contradictory experience to those who live in its spaces of extraction and refinement. The possibilities of modernity were manifested physically right in the middle of what would quickly become a sprawling city: in its spectacular, giant metallic embodiment, the refinery heralded prosperity and welfare, progress and happiness. And yet, these promises remained unfulfilled as Abadan was ravaged and forgotten.

Oil constitutes the dichotomies through which Abadani nostalgia reenacts history: its presence created order and discipline, its absence made society descend into chaos and disregard; oil endowed Abadan with prestige before it became a footnote in history; oil brought about cosmopolitanism, which has now been replaced by provincialism; oil gave healthcare, drinking water and agriculture, but also environmental degradation; oil generated electricity to lit up the streets of the world, but today cannot even secure Abadan itself; the magic power of oil fuelled imagination in spaces like the cinema, until those spaces burnt down, were bombed to pieces or simply closed and disappeared.

This discontinuity and suspension in time breaks with the teleological perception of modernity as the result of modernization following a clear and inevitable trajectory. The nostalgia hails the magic power of oil just as it is painfully aware of its tendency to destroy.

Abadanis have many reasons to reminisce about the past: to glorify it or to criticize it or to lament the ruptures that broke the city’s thrust into the future; or to forget about the ruptures and dream away to different futures that could have been.

Nostalgia cannot be reduced to a critique of the Islamic Republic, conservatism and economic recession, although these are important points to some. What unites nostalgia are the expectations to and experiences with modernity that oil engendered.

When a power-cut hits Abadan, the only thing that fills the darkness with light are the flames of the refinery. This makes it clear to everyone how contradictory and ultimately ephemeral modernity is.

…

This essay is part of a reworked version of:

Elling, Rasmus Christian. 2014. ‘Oliebyen midt i en jazztid: Nostalgi, magi og det moderne i Abadan’, Tidsskriftet Kulturstudier, 2/24: http://tidsskriftetkulturstudier.dk/kulturstudier/wp-content/uploads/webfil_rasmus-24-47_kulturstudier_2014-02.pdf

SOURCES:

Farrokhmehr, Ali. 2001. Âbâdân: Kuche-hâ-yemehrabâni, Tehran: Nashr-e Abed.

Farrokhmehr, Ali. 2011. Âbâdân: Khâk-e khubân, yâd-e yârân, Tehran:Najaba.

Valizadeh, Iraj. 2010. Anglo vabangolodarâbâdân, Tehran: SimiaHonar.

SUGGESTED READING:

On industrial urbanism

Alissa, Reem. 2013. “The Oil Town of Ahmadi since 1946: From Colonial Town to Nostalgic City”. Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 2013: 33, pp. 41-58.

Dinius, Oliver J. &Vergara, Angela 2011. Company Towns in the Americas: Landscape, Power and Working-Class Communities, University of Georgia Press.

Ferguson, James 1999: Expectations of Modernity: Myths and Meanings of Urban Life on the Zambian Copperbelt, University of California Press.

Fuccaro, Nelida 2013: “Shaping the Urban Life of Oil in Bahrain: Consumerism, Leisure, and Public Communication in Manama and in the Oil Camps, 1932-1960s”, Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 2013: 33, pp. 59-74.

On Abadan and its history

Bayat, Kaveh 2007: “With or Without Workers in Reza Shah’s Iran: Abadan, May 1929” inTourajAtabaki (Ed.): The State and the Subaltern: Modernization, Society and the State in Turkey and Iran, I.B. Tauris.

Crinson, Mark 1997: “Abadan: Planning and Architecture under the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company”,Planning Perspectives 1997:12, pp. 341-59.

Cronin, Stephanie 2010: “Popular Politics, the New State and the Birth of the Iranian Working Class: the 1929 Abadan Oil Refinery Strike”,Middle Eastern Studies 2010: 46, pp. 699-732.

Ehsani, Kaveh 2003: “Social Engineering and the Contradictions of Modernization in Khuzestan’s Company Towns: A Look at Abadan and Masjed-Soleyman”,International Review of Social History 2003: 48, s. 361-399.

Ehsani, Kaveh 2014: The Social History of Labor in the Iranian Oil Industry, the Built Environment and the Making of the Industrial Working Class (1908-1941), doctoral dissertation, Leiden University.

Elling, Rasmus Christian 2015: “On Lines and Fences: Labour, Community and Violence in an Oil City” in Ulrike Freitag, Nelida Fuccaro et al (Eds.): Urban Violence in the Middle East: Changing Cityscapes in the Transition from Empire to Nation State, Berghahn Books (forthcoming, March 2015).

Elling, Rasmus Christian 2015: “War of Clubs: Struggle for Space and the 1946 Oil Strike in Abadan” inNelida Fuccaro (Ed.): Violence and the City in the Modern Middle East, Stanford University Press (forthcoming, ultimo 2015).

Pirzad, Zoya 2013: Things We Left Unsaid,translated by F. D. Lewis, Oneworld Publications.

On nostalgia

Boym, Svetlana 2007: “Nostalgia and Its Discontents”,Hedgehog Review 2007: 9, pp. 7-18.

Davis, Fred 1979: Yearning for Yesterday: A Sociology of Nostalgia, Free Press.

Gross, David 2000: Lost Time: On Remembering and Forgetting in Late Modern Culture, University of Massachusetts Press.

On oil

Coronil, Fernando 1997: The Magical State: Nature, Money, and Modernity in Venezuela, Chicago University Press.

Damluji, Mona 2013: “The Oil City in Focus: The Cinematic Spaces of Abadan in the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company’s Persian Story”, Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 2013: 33, pp. 75-88.

Davis, Eric &Gavrielides, Nicolas 1991: Statecraft in the Middle East: Oil, Historical Memory and Popular Culture, University Press of Florida.

Limbert, Mandana 2010: In the Time of Oil: Piety, Memory, and Social Life in an Omani Town, Stanford University Press.

Mitchell, Timothy 2011: Carbon Democracy: Political Power in the Age of Oil, Verso.

Salas, Miguel Tinker 2009: The Enduring Legacy: Oil, Culture and Society in Venezuela, Duke University Press.

Vitalis, Robert 2007: America’s Kingdom: Mythmaking and the Saudi Oil Frontier, Stanford University Press.

Watts, Michael 2001: “Petro-Violence: Community, Extraction and the Political Ecology of a Mythic Commodity” in Nancy Lee Peluso& Michael Watts (Eds.): Violent Environments, Cornell University Press, pp. 189-212.

8 comments

The image referenced as Cinema Rex in the ’50s is incorrect.

As a followup to my previous comment: The pictured 1954 image of the cinema is Cinema Rex in La Goulette (French pronunciation: [la ɡulɛt]), known in Arabic as Halq al-Wadi (حلق الوادي About this soundḤalq el-Wād), is a municipality and the port of Tunis, Tunisia. I looked it up and it still stands in a much less glamorous condition today.

Hello, do you have a reference for the tennis club photo? It looks a lot like mother in the picture, but I am not sure about it and it was a very long time ago. Any information welcome,

Best wishes, Amanda