A guest post by Jonathan Paul Katz, a civil servant in New York City. He writes at Flavors of Diaspora, and has previously written at the Jewish Daily Forward, New Voices Magazine, Roads and Kingdoms, and Africa is a Country. He studied at the University of Chicago and the University of Oxford, where he witnessed many abuses of beautiful farsh. This article is in no way connected to his employment.

The year is 1970, and you, a white visitor from abroad, have been invited to an upper-class white home in Johannesburg, perhaps in the tony suburb of Sandton. Apartheid – “apartness,” a state-sanctioned racial segregation implemented by South Africa’s white minority government – is at its zenith, and wealthier White South Africans lead a lifestyle similar to their peers in the United States or the United Kingdom, albeit with domestic workers and the benefit of a race-nationalist political system even more rigged in their favor. The luxurious daily life of the sprawling houses of South Africa’s white élite have already been profiled in Life Magazine and glossy British publications as both comfortable and connected with the rest of the white and Western world – as they sought to remain fashionable and “up to date” with the North Atlantic.

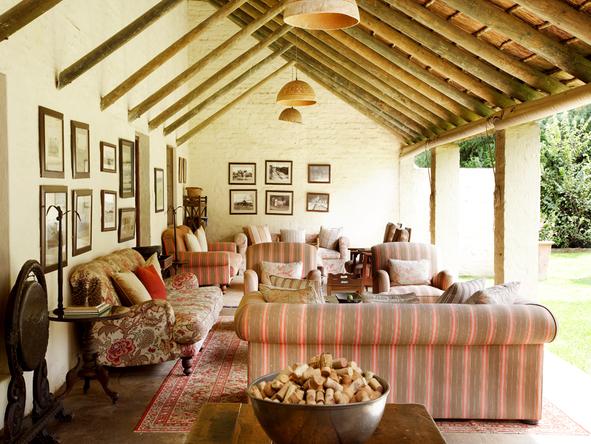

You enter, and you are greeted by your hosts, who direct you to the living room – or, as some South Africans would say, the “lounge.” You enter the room, perhaps holding a drink brought by a black maid given an English name, because your white hosts found her isiXhosa or isiNdebele name “too difficult.” You take stock of your surroundings: the chintz sofas, the billowing drapes, the 1950s-chic vases. There are doilies on the table and pictures on the wall; perhaps there is a print of a European painting. Nothing in the room is not Western. Except one thing: on the floor, you may notice something quite incongruous: the “Persian carpet,” or, for those who speak Persian, a farsh.

How did a farsh get here? To an upper-class white living room in South Africa, otherwise brimming with all the European kitsch anyone could ask for? The answer is not only a reflection of how South Africa and Iran alike were intertwined in a 20th-century world of global capitalism, colonialism, and commerce, but also how ideas of European “good taste,” propriety, and luxury have always relied on the products of colonized and semi-colonized regions. It is a story of appropriation and trade, and it is a story of a product’s transformation and role in the construction of whiteness in South Africa.

Let us begin in Iran itself. The farsh and other carpets and rugs have been produced and traded through the region since ancient times. By the Safavid period (1501-1732), rugs of various forms, including the flat-woven farsh so commonly called a “Persian carpet,” were spread throughout the Persian and Ottoman Empires, from Istanbul all the way to Tashkent. Already, similar Anatolian rugs were popular among wealthier families. But increased trade with the Ottoman Empire in the 19th century brought Europe in increasing contact with the farsh and other regional carpet types, which were sent from Iran via Istanbul to Europe. The carpets became wildly popular among the industrialized European upper-classes in the 19th century, who valued both their beauty and propriety – important in an age that cherished all things cozy and avoided all things messy.

Colonialism also plays a role. Anglo-Indians encountered the Persian weaving tradition in the Raj. Carpets were traded from Iran to India, and the British Empire had quasi-colonial ventures in modern day Iran itself. Both situations led to more carpets being brought “back” to the United Kingdom for wealthier members of the public. In an age where Orientalism and a taste for all things “exotic” was de rigueur, a “Persian carpet” – or, farsh, which comprised most of them – became another hot trend. Thus by the early 20th century, the “Persian carpet” was a key accessory in the performance of being upper-class or middle-class in the United Kingdom. Writers at the time – EM Forster and Henry James among them– appointed their bourgeois protagonists’ homes with many a farsh.

At this time, white, English-speaking people in South Africa looked to the colonial motherland for cues in all things taste. To be too “native” in one’s taste, and to not adhere to Victorian or Edwardian ideas of cleanliness or propriety, was to be a “failure.” In a general scheme of racial politics, it was a failure of whiteness, but I would like to note that it was also considered a failure of both class and South African identity as well. For the former, being upper-class was closely tied to how “civilized” (read: English) you were. Lower-class whites, racially benefiting from whiteness but not from class in pre-1948 South Africa, sought all things European: dress, clothes, culinary habits, even names. For the latter, a national South African identity for whites, by whites was being constructed and promoted in mass media through the lens of another colonial settler society – in Afrikaans and English alike. Afrikaner nationalism would later famously borrow this concept, but in South Africa for a very long time, the ultimate in being white was being as “white” as possible in one’s taste. A bush warrior on the outside, but a metropolitan living room at home.

“Persian carpets” were among these commodities. The farsh probably reached South Africa in the late 19th century, and were certainly purchased by some of those who “struck it rich” during the 1890s gold rush. At the same time, the architecture and interior décor of upper-class Europe were both imported to South Africa by the largely white mining barons – and these determined an élite aesthetic that held significant power in South Africa through at least the beginning of apartheid in 1948. Meanwhile, the increased carpet production mentioned earlier in this piece allowed more farshs to be sold outside Iran, largely in the Western-controlled economic arrangement into which Iran was locked. On the other side, a small slice of that production was accessible by White South Africa. By the 1960’s, the Persian carpet was a welcome part of a proper, English-speaking, white middle-class home. In fact, there was a certain elegance attached to it.

But South Africa changed. The end of apartheid in 1994 also heralded a new standard of taste for wealthy White South Africans: the high European style that had held sway, in various iterations, for a century was no longer hegemonic among White people. (In fact, it was never universal.) These items were seen as stuffy and indicative of a certain backwardness – a desire to retain the “old South Africa.” In the years prior to democratization, the international sanctions regime placed on South Africa had also moderated the tastes and expenses of an élite now hard-pressed to acquire imported goods. Items like the farsh were both prohibitively expensive, and seen later as outdated. Even an imitation would have been considered in bad taste – it was, to put it politely, “dated” in an era when the old ways of South African Whiteness were – at least in public – seen as increasingly unacceptable. And so the “Persian carpet” was relegated with tea parties and modular kitchens to the pile of discarded élite whiteness.

What was in vogue now among the white élite? African patterns such as Ndebele color schemes and celebrations of an essentialist (and Orientalized) “Africa” came into vogue. A new appreciation for indigenous culture? Perhaps. But in a South Africa that continues to be vastly unequal economically across races, is this an attempt by the white élite to perform cosmopolitanism without living it out? Possibly – alongside a good deal of cultural appropriation without appreciation too. Or, as bell hooks noted, “Within commodity culture, ethnicity becomes spice, seasoning that can liven up the dull dish that is mainstream white culture.” “Persian carpets” and Ndebele patterns alike serve this purpose.

It is a fascinating accident of history that “Persian carpets” became a part, albeit a small one, of South African whiteness. On the one hand, one could simply call this history another example of cultural appropriation. Yet the example of how an Iranian product became a luxury good that connoted a specifically Western and white high-class status says far more about the way in which goods become commodities, commodities are traded, and how items thus become highly prized symbols of wealth and culture.

In the South African context, it is a crystal-clear example of how “cosmopolitanism” and the “exotic” both served whiteness and helped construct it – even if the farsh was less common than Cape Dutch or Neo-Baroque architecture. Let us not forget, however, that White South African trends and tastes were always and still are tied to white tastes elsewhere. What does this South African example tell us about how “Persian carpets” are perceived in larger markets, such as the United Kingdom? Where else do we see Iranian products folded into White aesthetics? In a time when the lifting of sanctions has renewed European and North American interest in Iranian luxury products, perhaps the conversation is not yet over. Perhaps, indeed, carpets shall be in vogue again.