Part II of a guest post written by Afsheen Sharifzadeh, a student at Tufts University focusing on Iran and the Caucasus. This article is part of a series on Armenian-Iranians. Check out Part I, “The Bridge to New Julfa: A Historical Look at the Armenian-Iranian Community of Isfahan” here, as well as “Towards an Armenian-Iranian Modern: Tehran Church Architecture and Post-Revolutionary Soccer Culture” here.

The Safavids left an appreciable Caucasian imprint on Iranian society by interweaving Armenian, Georgian, and Circassian elements into the socio-political fiber of the empire. Promising young Caucasian men were trained to become politically-influential ghulâms, or royal pages, and Shahs, governors, and commanders alike were born of Caucasian mothers. In fact, the sepâh-sâlâr (Commander-in-Chief) of the Persian armies in Afghanistan and appointed Governor of Kandahar in the early 18th century was none other than the former King Giorgi XI of Georgia, under the Persian allonym “Gorgīn Khan”.

But Shah Abbas I had a unique vision for a certain group of Armenians, and among his greatest achievements was his creation of a semi-autonomous Armenian merchant oligarchy in his new capital, Isfahan. In this exclusive, custom-built suburb called New Julfa, the Armenians were permitted if not outwardly encouraged to preserve their distinct cultural, linguistic and religious identity, while melding harmoniously with the sovereign Persian socio-political infrastructure. Indeed, the Armenian merchant community of New Julfa became the crown jewel of the Safavid economy in the 17th century.

Few people realize that some common words in English are vestiges of the Iranian silk imports to Europe. For example, the word “seersucker” comes from the Persian shīr-u-shakar, which means “cream and sugar” and denotes a thread color. The more familiar “pajamas” are from the word pâ-jâmah, the contemporary word denoting trousers in Persian. Many other terms relating to textiles and clothing came from Persian into European languages as a result of New Julfan trade interactions.

The merchants of New Julfa were among the wealthiest merchants in the Old World by the end of the 17th century. Contemporary French traveler Jean Chardin wrote that, in 1673– just two generations after the Julfan Armenians were exiled from the Caucasus to Iran– Agha Piri, the head of the Armenian Community of Isfahan and one of its richest merchants, owned a fortune greater than 2,000,000 livres tournois (the equivalent of 1,500 kg of gold). Contrast with the textile merchants Beauvais and Amiens (the wealthiest merchants in France in the same period), the wealth of these two inventoried at their deaths amounted to 60,000 and 163,000 livres tournois respectively—a figure then considered astronomical. Yet these two figures combined amounted to barely a tenth of Agha Piri’s fortune.

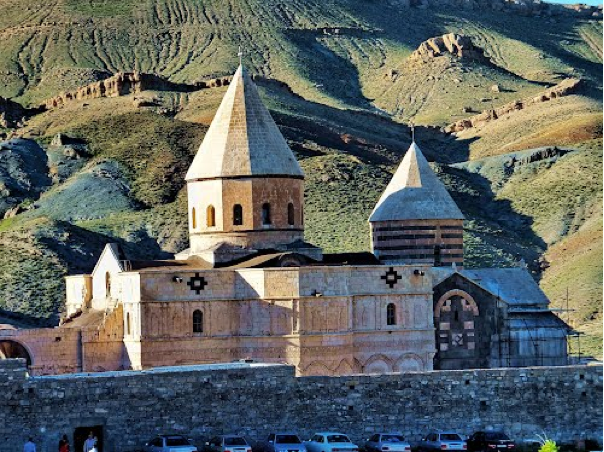

The Safavids were determined to please the New Julfans while simultaneously transforming their exclusive suburb into a strategic center of religious and mercantile activity for Armenians around the world. Indeed this royally-backed centrism effort is reflected in the official Armenian title for the provost of the suburb, Hayots T’ak’avor (“King of Armenians”). Shah Abbas I even issued a farmân in 1615 to dismantle the holiest church to the Armenian Orthodoxy, the Echmiadzin Church in the Caucasus, and have the stones transported to New Julfa and reassembled to form a new mother church for the Armenian people according to the architectural taste of the Armenian clergy in Isfahan. The New Julfan merchant council however staunchly opposed this act, and eventually settled for the removal of just a few foundation stones for the construction of the superficially mosque-like Vank Cathedral (Sourp Amenaprgich Vank). The Catholicos of Echmiadzin approved the creation of a new “Diocese of New Julfa” in Isfahan, which became known as the “Diocese of Persia and India” (Parska-Hndkastani T’em) headed by the “Archbishop of New Julfa”, and had jurisdiction over all Armenian communities in Persia, India, and Java.

It is only logical that the relationship between the New Julfans and the Safavid royal family was incredibly warm and politically-loaded, for these merchants were the wealthiest lot in the realm behind the Shah himself. A notably prosperous and powerful early provost of the suburb, Khoja Nazar of the Shafraz family, is even called “Shah Nazar” in Persian mercantile documents–a faculty that was unthinkable for any of his Muslim contemporaries.

The Shah allowed the New Julfans to wear their distinctive Armenian garbs and headgear, and ruled unconditionally in their favor in disputes with Muslims. At the request of the New Julfans, the Shah issued a farmân forbidding European evangelists such as Franciscans, Capuchins, Jesuits, and Carmelites from proselytizing in New Julfa. Most notably, he stopped the schemes of a certain Portuguese Augustinian monk in Isfahan named Diego who sought to align New Julfa with the Roman Catholic Church and bring the Armenians into communion with the Papacy.

Prominent New Julfan families even made a regular tradition of inviting the Shah to their mansions to celebrate Christmas festivities and “Epiphany”, wherein children born up to two months before Christmas were baptized in the Zâyandeh Rûd in the Shah’s presence. Tavernier gives a splendid account of Christmas meals, wherein the Shah’s gold tableware would be transported from the palace to the host’s house along with food from the royal kitchen. After the meal, the Armenians would offer magnificent gifts including large amounts of silver, gold, and valuable gifts of European origin to the Shah in gold basins. But this was nothing much compared to the principle gift that went to the Shah’s mother on Christmas Day.

The Armenians of New Julfa served as brokers on behalf of Persia in both commercial and political contexts due to their common faith with Christian Europe and their familiarity with the languages and the traditions of the peoples of both East and the West. The provost (kalântar) of New Julfa was chosen to hold official receptions of foreign embassies to Isfahan on the Allahverdi Khan bridge (later renamed Si-o-Se Pol), and the Armenians acted as a welcoming committee often introducing foreign visitors to the court. Hovhannes Vardapet, a native of New Julfa, introduced the first printing press into Persia from Italy, and the first book printed in Iran was the Armenian Saghmos (Psalms) in 1638. It was also the Armenians of New Julfa who reportedly supplied the Shah with 200 modern European firearms—the first of their kind in Iran—during the fall of Isfahan to the invading Ghilzai Afghans in 1722.

The Armenian vernacular of Isfahan developed a highly distinct character from other Eastern varieties of the language marked by sound shifts under influence from Persian, retention of Armenian lexical and phonemic archaisms (most notably the alveolar pronunciation of “Ր” as <ɹ> that is highly distinctive of modern-day Isfahani Armenians), and the vast number of Persian loanwords, phrases, and calques (i.e. coll.P tamūm shod o raft → JA verchatsav gnats) that made their way into everyday speech. Among these lexical borrowings was “akhtibar” (from Persian<Arabic e’tebâr, although Armenian pativ and Persian nâmûs also appear in New Julfan documents) to denote the concept of “trust/reputation/credibility”, which served as an honor ranking system that distinguished merchants from their peers and dictated their livelihoods in commercial affairs. Like other mercantile communities, the New Julfans relied on an ethos of trust through kinship ties and marriage in order to carry out business transactions, and thus this system of social trust played a critical role in guaranteeing collective and individual benefits within the network. The New Julfans even created their own calendar, the Azaria Calendar, which began with the year 1615 as year One on the day of the Persian New Year, March 21st, and was used for all New Julfan commercial documents and merchant accounts throughout the world.

But just a few generations after the foundation of this semi-autonomous Armenian merchant republic, the ethno-religious climate began to darken in Isfahan. A court intrigue-turned-deadly resulted in the murder of the Grand Vizier Saru Taqi on account of embezzlement from the Queen Mother, Anna Khanum (the mother of the still juvenile Shah Abbas II), herself a Circassian convert. The result was the appointment of a religiously intolerant Grand Vizier named Khalifeh Sultan whose sporadic policies of persecution and forced-conversions targeting Christians, Jews, and Zoroastrians all but killed these religious minorities and nullified many of the social and economic privileges granted specifically to the merchants of New Julfa by previous Shahs.

In the aftermath of this upheaval in 1671, the majority of the wealthiest merchants permanently left Iran to seek hospice in India, the Ottoman Empire, Poland, Russia, and Italy—where they had strong commercial ties and even owned property. The “kingly” Shafraz family emigrated to Russia, while the Shahrimanian family was granted freedom of customs at Ancona and immediate citizenship in Rome, and were even ennobled as “Counts of the Holy Roman Empire” under titles such as “Conte Marcar” and “Conte Stefano”. The gated, exclusive suburb of New Julfa first transformed into an Armenian quarter and then into something of a Christian ghetto interspersed with Muslim and Zoroastrian families by the end of the 19th century, but Armenians continued to live there under loyalty to the Shah.

Petros di Sargis Gilanentz, a member of one of the twenty prominent Armenian families ruling the civic affairs of the suburb with strong ties to Russia and Venice, reports that during the Afghan invasion of 1722 the invaders forced the New Julfans to supply tens of thousands of satin coats to their army, and they later abducted 62 Armenian girls. After this most grievous blow coupled with the new coercive taxation policies of Nader Shah Afshar in 1747, a few hundred remaining families fled Iran, never to return, and while a number of Armenian merchant families continued to live there, the unique cultural heritage and economic significance of the suburb slowly vanished. Inspired by the wealth of New Julfa, Nader Shah nostalgically attempted to create an Armenian suburb in his new capital Mashhad called Nor Nakhchevan (“New Nakhchivan”), but alas his efforts were in vain.

While most of the finest mansions of New Julfa have been pillaged or destroyed since the 17th century beginning with the Afghan invasion in 1722, we can still marvel at the remains of the Sukas House and the House of Khoja Petros in the modern district of New Julfa in Isfahan that combine elements of Persian, Armenian, and Western European architecture and mosaic. Thirteen of the twenty-four churches of New Julfa still remain standing today, most notably Vank Cathedral in the center of the suburb.

And of course four centuries later, Christmas among the Armenians of Iran is a far more humble but nonetheless delightful celebration. While the story of New Julfa is a gem in the history of Iran and Iranian Armenians, which also includes periods of persecution and forced conversion and migration, it’s a pleasant reminder–a reminder of the diversity and multi-faceted nature of the Iranian identity, the struggles it has toiled with and painstakingly overcome, and the enduring hope of its constituents to rebuild their nation stone by stone on the same platform of universalism and dignity upon which it so elegantly once stood.

–

Sources

“Julfa Safavid Period” — Vazken S. Ghougassian

The History of the Revolutions of Persia — Tadeusz Jan Krusinski

“Georgia viii. Georgian communities in Persia” — Pierre Oberling

7 comments

Reblogged this on Notes of a Spurkahye.

Awesome…:O i really proud of u bro