This article was originally published on Jadaliyya.com and was part of Visuals in 1500, a Jadaliyya Culture series on aesthetics. For more images of marriage contracts, visit Women’s World in Qajar Iran, a website and digital archive of everyday items from the Qajar period.

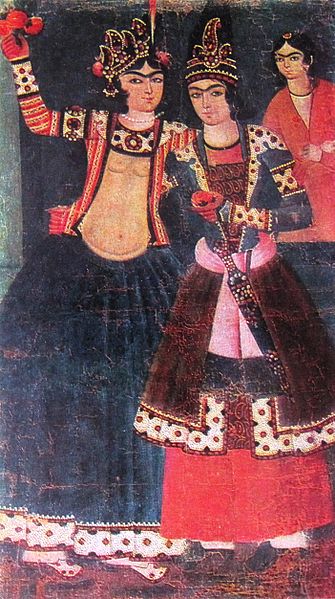

During Iran’s Qajar period (l785-1925), when wedding memories were ephemeral—specialized photographers or videographers were not available quite yet—artifacts like the marriage contract became the material substance through which sacred unions were validated and remembered. These inherently practical documents were stunning works of art as well, with which families could express social status, engage in trends, and, in some cases, masquerade their identities.

As the major “souvenir” from Iranian weddings, the marriage contract served as a tool for newlyweds and their families to declare their class and confessional associations in written form. The marriage contract, then, not only reflected how families were seen in society, but rather, demonstrated how they wanted to be perceived. By taking the dower, the language, and the ornamentation of the contract into consideration, one can see how a document as simple as a marriage contract encompassed complex discussions of identity in its aesthetic beauty.

Marriage contracts were presented at the ‘aqd, or wedding ceremony, where the couple was legally married. All contracts were dated, signed, and stamped with an official insignia to verify their legitimacy.

Generally, most marriage contracts adhered to a similar formula, beginning with Qur’anic verses and prayers in the beginning and ending with the dower (gifts given from the groom to the bride). Although they were only mentioned in the last section of contracts, dowers were arguably the most important element of the document. Essentially, the dower legitimized the marriage and safeguarded the bride in case of a divorce. Dowers promised to the bride included a variety of items, most commonly including money or gold.

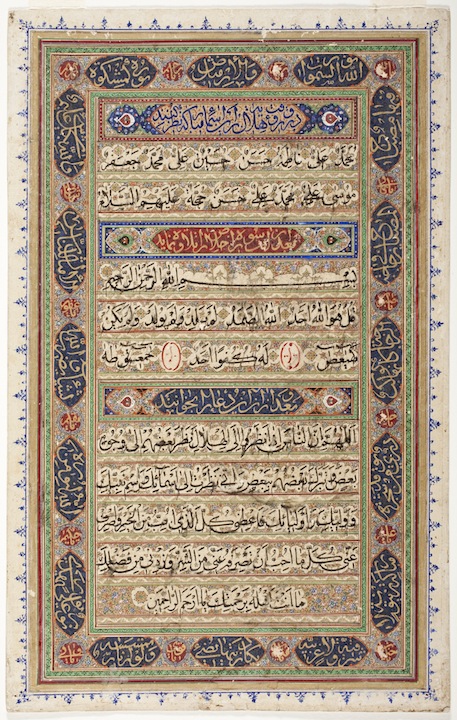

Although the contract’s core purpose served to validate the marriage of the two individuals through the promise of a dower, the actual document was a multi-function piece that was often beautifully constructed in order to honor the bride and groom with additional prayers to increase blessings on them and their marriage. Longer contracts belonging to Muslims included various Prophetic sayings at the beginning, in an effort to acknowledge righteous examples of character and morality. The longer and more elaborate the contract, the more prayers included, ensuring a healthy union.

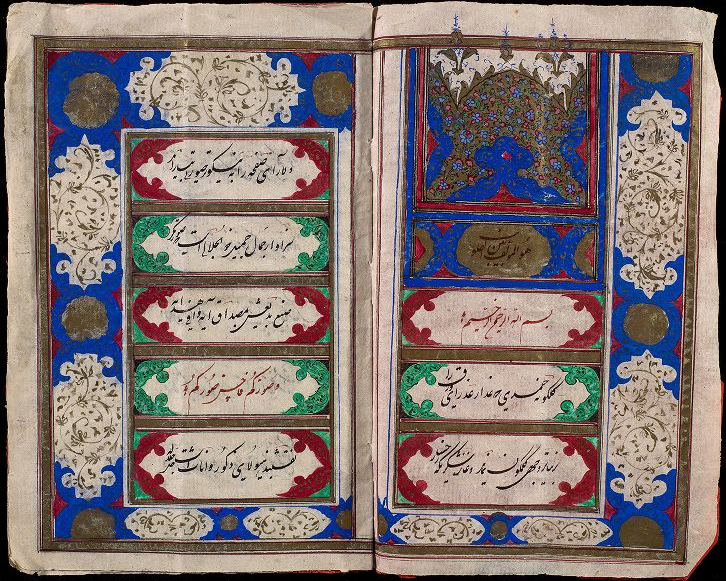

Contracts were often decorated in vibrant colors and written in elegant calligraphy in both Arabic and Persian. While Persian was the predominant literary language and mother tongue, Arabic was and continues to be widely respected in Iran as a language of formal communication and is favored for ceremonial purposes.

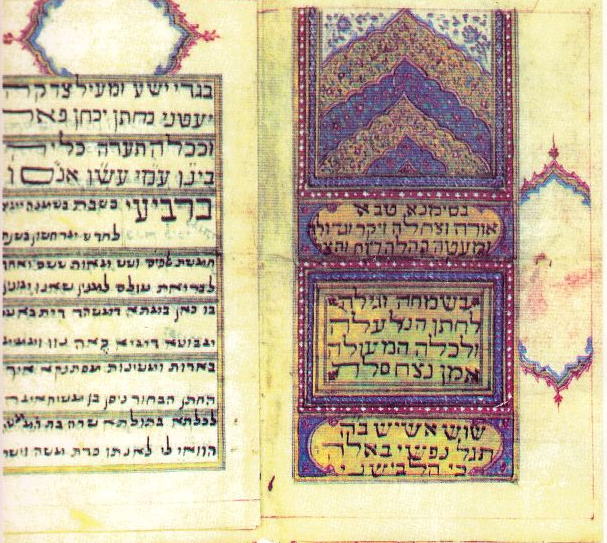

The practice of opening with the Qur’an was not limited to Muslim families. Surprisingly, there are several examples of Jewish marriage contracts with either the incorporation of both Arabic, Hebrew, and Aramaic as the holy languages of the contract, or the sole use of Qur’anic lines in addition to the Persian text. The use of one language over another amongst certain groups reflected the position of a community. Thus, the use of Hebrew, Aramaic, Arabic, and Persian on one document could suggest that a community was well integrated; however, it could also suggest the opposite.

A few examples of these marriage contracts from Jewish Iranian families in Mashhad in the late nineteenth century, reflect the lengths to which the Jewish community maintained a Muslim-coded external identity for the sake of their safety after the 1839 Allahdad incident. “Allahdad” refers to a riot that resulted in the killing of over thirty Iranian Jews and the kidnapping of some younger girls in the Mashhadi community, after which many Jews decided to mask their identities and continue living in Mashhad under the guise of being Muslim. The pogrom pushed Mashhadi Jews to hide their identity behind imitations of a Muslim lifestyle. The crypto-Jews, known in Hebrew as the Anusim, were specific to the Mashhadi community—other Iranian Jewish communities were able to practice their religion openly.

These marriage documents, although belonging to these families, mimicked Muslim marriage documents in both presentation and content. The documents were titled with the phrase “in the name of God, most Merciful, most Kind,” and the verse “He is the one who brings hearts together,” phrases taken from the Qur’an and presented in the documents in their original Arabic. The first line of such documents was also formulaic, praising God for the union in a ceremonial form of Arabic. The careful degree to which Jews copied the Muslim contracts demonstrates the conscious effort made towards assimilating to a public Muslim identity; only some names, such as “Ya’qub” (Arabic for Jacob) hint towards a possible Jewish background in the marriage contract.

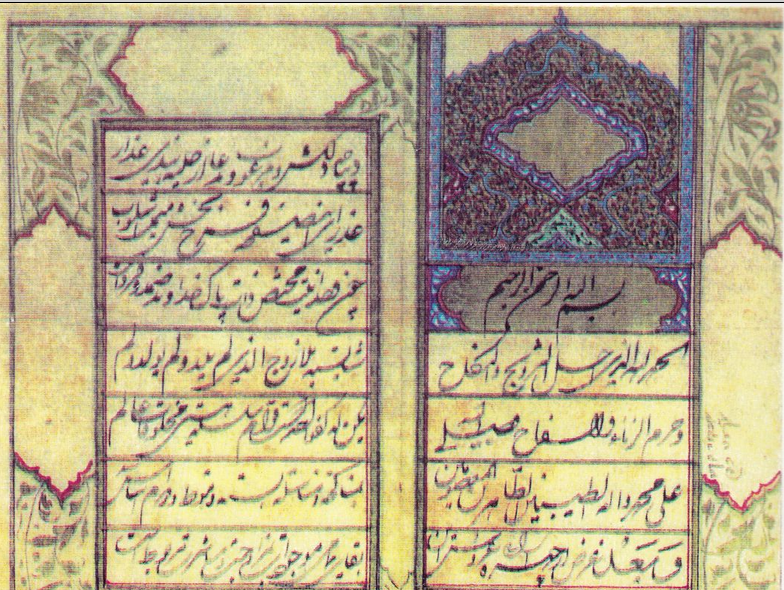

Despite pressures to conform to an outwardly Muslim appearance, some families managed to preserve their identity in written form as well. Some marriage contracts embraced a hybrid expression of Muslim and Jewish practices. This one, for example, has two identical pages: one in Hebrew and Aramaic, and the other in Arabic and Persian. The combining of these languages and collapsing of identities in marriage documents similarly encapsulates the critical social and political pressures on the Mashhadi Jewish community. It is possible that the family had two contracts made, one for display, and one for themselves to reflect their Jewish identity.

In their historical importance, these marriage documents also indicate a world beyond the nineteenth-century Iranian context during which they were written, pointing towards a history of continuity and change. The singular pressures on Mashhadi Jews to conform during this time had a long, lasting impact; later, when they emigrated from Iran, they upheld their distinct identity, many marrying from within their tight-knit communities, while keeping to themselves among larger Jewish populations. Today, separate Mashhadi Jewish circles are maintained in Israel and New York.

The precarious socio-political climate of Mashhad, however, was not representative of the broader Jewish Iranian experience in nineteenth-century Iran. The Mashhadi Jewish marriage contracts were unique essentially because their situation was unique. Elsewhere in Iran, Iranian Jews were able to practice their religion freely, which meant their marriage contracts resembled traditional ketubahs and were bereft of any Arabic. Despite whatever instances of discrimination Jews encountered in day-to-day contact with other Iranians, creating a Hebrew and Aramaic language document indicated the ability of Iranian Jews to maintain a public identity in Qajar Iran.

While language and religion highlight significant social issues within the contracts, the art of the contracts are a common thread across religions in certain social strata. The uniformity of the contracts highlights the preferred aesthetics of nineteenth-century Iranians, regardless of their religious affiliations. Elites of every religious community managed to produce beautifully gilded contracts, which look quite similar when the different languages are overlooked.

Red, blue, and gold paint adorned many of these contracts and framed the text in bright flowery designs. If the contract was more than a page long, as became customary in the later half of the nineteenth century, the first page of the contract was the most ornate. The actual text began halfway down the first page, leaving room for decorative artwork called a sar lowh, mimicking the borders around classic manuscripts of poetry or miniature paintings.

Many contracts had flowers, diamonds, and other shapes painted symmetrically around the body of the text in watercolor, representing the balance their families hope for in their symbolic union. The decorative elements, especially the floral and geometric frames, reflected traditional Muslim and Jewish preferences for avoiding graven images in religious documents.

Not all contracts, however, were drafted with such pomp, and some contracts remained simply executed, with black ink nastaliq calligraphy on white sheets of paper. Despite their modest presentation, these contracts were still written and stamped by a scribe. Even without the colorful and intricate designs, the calligraphy allowed for the contract to be conceived of as an aesthetically pleasing piece of art.

The art of a marriage contract, therefore, was not a necessity, but rather, a privilege enjoyed by the upper class. The similarity between tastes, however, demonstrates the evolution of style as disseminated throughout the population. Despite the rigid religious associations that isolated some communities from each other, there is a uniformity that pervades the contracts, indicating a greater sense of belonging to Iranian society that is often overlooked.

By taking the contract in its entirety into consideration through the projection of identity, status, and artistic value in textual form, the intersections between class, image, and visual culture in Qajar society emerge as definite patterns present in the marriage process.

1 comment