This is the second article in a three part series exploring rap in Pakistan. It profiles two Pakistani rappers, a Sindhi and a Punjabi, rhyming to preserve language and reinvigorate ethnic traditions. The first essay of the series, tracing the development of contemporary Pakistani rap productions, is available here.

* * *

Thatta is a historic city in south-eastern Sindh renown for its ancient necropolis, which is among the largest in the world. Once a Sindhi cultural capital, it is now among the smaller cities of a Pakistan bifurcated into the mega-metropolises of Lahore, Karachi, Islamabad and Peshawar, and everything else. Shahzad Meer, or Rapper Meer Janweri, grew up in Thatta. His parents are from Dadu, a comparably sized Sindhi city about 300 kilometers north of Thatta. His grandfather moved from Dadu to Thattha. Shahzad’s Sindhi is accented with the twangs of Dadu the crispness of Thattai Sindhi. “Northern Sindhi,” he describes it.

He responds excitedly when I ask him why he raps in Sindhi.

“I was hoping you would ask me that! When you arrive in Thatta, the ricksawallah (rickshaw driver) has an Urdu song playing, maybe a Punjabi song, maybe even an English song, but never a Sindhi song. What has happened to the rich musical tradition of Sindhi?”

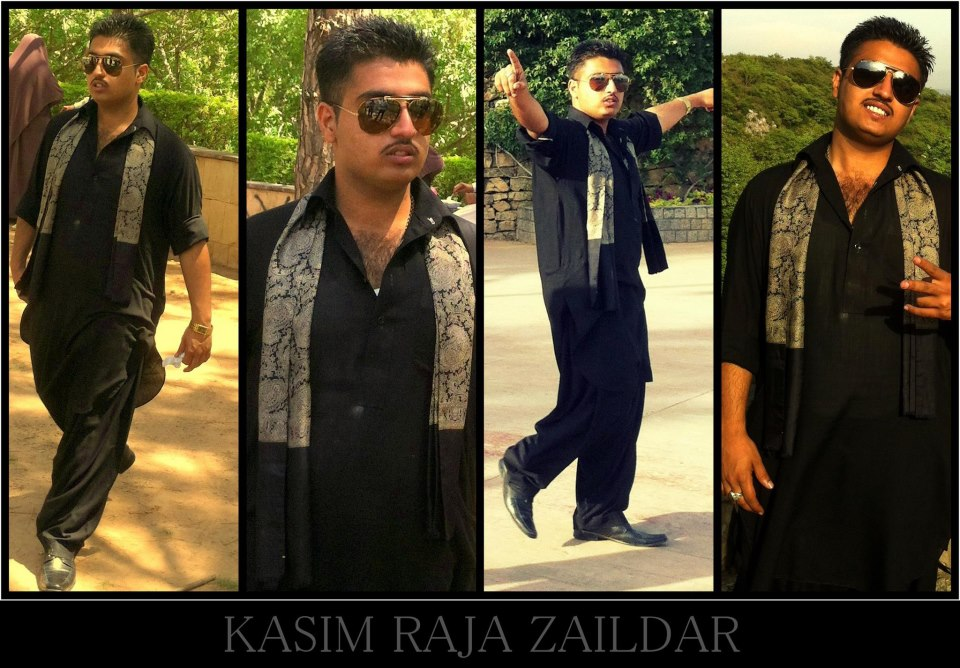

Language and culture are also center-stage in a chat with Kasim Raja, a rapper from Jhelum in Punjab. Kasim’s rhymes pointedly eschew Urdu, associated with urbanity and ushered by the strongarm modernism of the state. He raps in Punjabi, Jhelum’s language of centuries of vintage.

“People don’t know their heritage,” Kasim says. “Punjabis who live in large cities such as Lahore don’t know what village they’re from. A Punjabi without a village has no value. People who forget their history can never prosper.”

* * *

The arrival in Pakistan of the productions of San Francisco-based Punjabi rapper Bohemia invigorated the country’s rap movement. The rhymes had been languishing shackled to English; Bohemia introduced them to the fiery and familiar vernacular of Punjabi. The contours of Bohemia’s popularity — and the linguistic indigenization of Pakistani rap that his music sparked — were deeply dictated by the history of language politics in the country.

Language and identity have had a torrid history in Pakistan stretching back to the formation of the nation, when Urdu was prioritized as a marker of national identity. Identified as the language of the Muslims, Urdu quickly found itself the beneficiary of the literary and intellectual largess of right-wing nationalists, who were eager to consolidate a narrative for the new ‘Muslim’ country. Other languages found themselves unwelcome in this story. The mother tongue of less than a tenth of the country, Urdu was crafted as the language of the people and was aggressively foisted on the linguistically diverse new country.

Resistance from partisans of Pakistan’s other languages was strident. For Shahzad’s province of Sindh, Sindhi linguistic nationalism emerged as a force with the creation of the country. Tensions between Urdu speaking Muhajirs (post-partition migrants from India) and the indigenous Sindhi-speaking population became increasingly hostile with the amalgamation of West Pakistan into a single administrative entity in 1951. The erasure of Sindh as a province under this “One Unit” scheme closed the space for Sindhi to be recognized and implemented by the state as a provincial language. Like other Pakistani languages, Sindhi was subordinated to Urdu, which became the Unit’s official language. This perhaps became the foundational quarrel between Sindhi and Urdu partisans.

Subsequent tensions bubbled into some of the most violent riots in Pakistani history. In 1972, after the loss of East Pakistan, and under ethnically Sindhi Prime Minister Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, the Sindh Legislative Assembly began to consider instituting Sindhi, alongside Urdu, as a required subject from grade 4 to grade 12 in all schools.

So ferocious was the Muhajir reaction that a July 1972 editorial in the Urdu daily Jang was headlined, “Urdu ka jinaza hai, zara dhum se nikle” (“it is Urdu’s funeral; let’s see it out with bombast”). The riots that followed were among the worst in the country’s history.

In 1983, under the dictatorship of Zia-ul Haq, whose emphasis on Islam as a national unifier privileged Urdu as a salient means to achieve this unity, Sindhi-language nationalists rioted against Urdu-language public signage in rural parts of the province. Sindhi nationalism was not confined to the rural areas, and in 1988, nationalists opened fire in Hyderabad, killing mainly Muhajirs.

Rapper Meer Janweri – Shahzad – is quick to assert he is no advocate of violence, and takes pains in his track Piyar Jo Siphai to advocate ethnic harmony, However, his rueful reflections on the absence of Sindhi from the ricksawallah’s playlist follow a trajectory of Sindhi language rejuvenation against the Urdu-ization of Pakistan by the state.

* * *

“I look at myself, and ask, am I Sindhi? Yes, and Sindhi is my language.

Then why am I listening to Bohemia?”

* * *

One day in 2006, a few years before Bohemia’s music became popular in Pakistan, Shahzad tuned into the radio and heard a Bohemia track. Previously unfamiliar with rap, and immediately struck by the heavy bass that is the hallmark of many Bohemia songs, Shahzad called the radio station to ask who was playing.

Quickly, Bohemia became a foundational artistic inspiration for Shahzad. Shahzad soon had Bohemia’s tracks on repeat even though he didn’t fully understand the rapper’s Punjabi. Shahzad says that it was in fact through Bohemia that he has learned a majority of his Punjabi. “Aur aap toh jante hain idhar Punjabi aur Sindhi ke taullqat idhar kaise hain” – “You are aware what Punjabi and Sindhi relations here are like,” he adds pointedly referencing tensions between the two ethnicities.

Listening to rap inspired a deep passion in Shahzad, one that needed urgent expression. In 2009, he produced his first track, a remix of a Bohemia song. Although Shahzad had no lyrics on the track, he had been penning Sindhi poems since early in his school days, publishing them in his school’s magazines. These poems soon found a place in his subsequent tracks, and transformed into the rhymes of Shahzad’s first Sindhi rap tracks.

But these rhymes weren’t just in Sindhi.

Shahzad is sensitive to the porous boundaries of languages, and to the osmosis of Urdu words into Sindhi vocabulary. His rhymes retreat into a carefully cultivated “pure” Sindhi. “Pakki sindhi – jaise kehte hain juttaan wali Punjabi,” he says – hardcore Sindhi, like Jutt Punjabi – referring to a Punjabi popularly perceived as relatively free of Urdu influences.

Shahzad’s rap attempts a resurrection not only of a distinct Sindhi language, but also a Sindhi culture. His songs aren’t just in Sindhi, he also sees them as a continuation of the long Sindhi tradition of Sufi poems. While other Pakistani rappers, prominently BillyX, rap about topics deeply taboo in Pakistani society – sex and intoxicants – Shahzad seeks to reinvigorate a more traditional subject matter. But why through rap? Why resuscitate a tradition through a medium that is foreign to it? He likens it to wearing western dress when going to school; the medium does not compromise the message.

* * *

“What language do you most like to speak?” “Sindhi,” says the Sindhi. “Pashto,” says the Pakhtoon. “Balochi,” says the Baloch. “Urdu,” says the Punjabi.

Description of the dialogue between the characters of Ahmed Farhani’s play, “Skit # 5” from Punjabi Zaban Nahi Maray Gi (The Punjabi Language Will Never Die). Published circa 1980.

* * *

Like Shahzad, Punjabi rapper Kasim Raja aims to rejuvenate a linguistic and cultural identity through his rap. But, unlike Sindhi, Punjabi ethnic identity has arguably held a less marginal space in Pakistan. Punjabis are seen as the hegemonic ethnicity in Pakistan, and taunts of ‘Punjabistan’ are not infrequent.

Although Punjab enjoys a privileged position in Pakistan, Farani’s 1980s play introduces an important dimension. While the other ethnicities in the play identify their own language as their favorite tongue, the Punjabi says their favorite language is Urdu. Certainly, urban elite Punjabis have frequently been implicated in promoting Urdu over their own language, and the theme of having sold one’s history makes frequent recurrence in Punjabi revivalism.

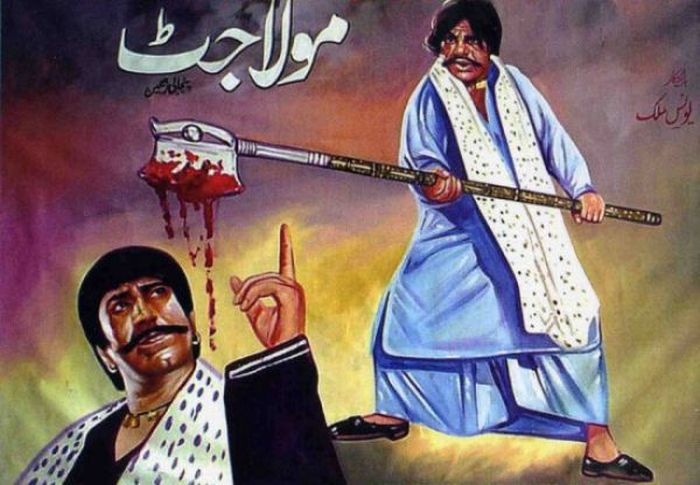

The Punjabiyat movement, which had been dormant for several decades, gained new vigor in the early 1980s. The introduction and meteoric box-office rise of gore-violence films featuring the character of Maula Jat, a recognizably archetypical rural Punjabi as a protagonist gave Punjabiyat expression in popular culture. Maula Jat was hyper-masculine, of recognizably rural and “authentically Punjabi” sensibilities, and a stark divergence from the suave, urbane Urdu-speaking protagonists who had dominated the silver screen in the preceding decades. Immediately identifiably cultural artifacts of rural Punjab were mobilized: barrak, the practice of verbal dueling, and the gandasa, the traditional axe of Punjabi sugarcane harvesters featured prominently in Maula Jat’s arsenal.

Concurrent with this vitalization of rural Punjabi masculinity in popular culture was an invigoration of Punjabiyat in literary high-culture. Led by Urdu- and English-literate Punjabi elites, Punjabi language literature was intrepidly politically charged, and sought to recall in Punjabi minds historic Punjabi heroes forgotten by the state’s national narrative. Historical folk figure Raja Puran of Sialkot, Sikh anti-colonial icon Bhagat Singh, and Dulla Bhatti who resisted Mughal Emperor Akbar’s annexation attempts were prominently mobilized for a historically vigorous Punjabi identity. The reclamation of a lost selfhood became a central concern of this literature, and Urdu was stridently denounced as a cannibalizing language that had devoured Punjabi identity. This was an unacceptable departure from the neatly deconflicted official history, where all subcontinental Muslims lived in harmony. Not surprisingly, several of these publications were banned.

Kasim Raja’s rhymes resonate strongly with these themes. “I could have started rapping in Urdu, but I am not just rapping. I am rapping because the Punjabi village life appeals to me, and I want to promote the Punjabi language, and the lost Punjabi culture.”

The location of authentic Punjabiyat in the village and in historical heroes is prominently evident in Kasim’s tracks. It is no accident that his first production, Puran, is an homage to his ancestral village. “I want to highlight my village,” he says, and the desire is obvious. Other tracks such as Number 1 Pind offer such details of Puran’s history as who founded the village (Raja Pahar), and when its first official school was established (1905). Similarly, the lyrics of an upcoming track feature the Punjabi nationalist heroes of Bhagat Singh and Dhulla Bhatti.

This rediscovery of the Punjabi ethnic self in Muslim as well as non-Muslim historical figures is consonant with the greater Punjabiyat movement, which affords an inclusive identity that welcomes Indian and diasporic Punjabis. “My father used to tell me of a time when Sikhs used to live next to us as neighbors. Punjab used to be one,” says Kasim Raja, “we have one blood, we look the same, and we get up to the same antics.” He looks to his Indian counterparts as examples of Punjabis who successfully and appropriately assert their ethnicity. “Look at the Indian musicians; they work their Punjabi culture into their songs.”

A photograph promoted by Kasim Raja’s official Facebook page

This pan-Punjabiyat affords an avenue to diasporic Punjabis to influence movements back in their regions of origin. In Pakistan, diasporic Punjabis find space in Punjabi identity in ways that parallel the reception of NRIs (Non-Resident Indians) in neighboring India. The financial remittances resultant from mass Punjabi emigration are a frequent source of pride in the community. Kasim raps:

“Munde gaye saday UK, USA / Mehnat naal kamay kinne kinne paisay / Holi holi inna ne note gar vaije / Hon vade vade ghar vekho kaise kaise.”

“Our boys went to UK, USA / With hard work they stacked money / Steadily they sent notes (money) home / Now look at all these magnificent houses”

But this close linkage with the diaspora is also a source of concern for the official national narrative. As Indian rapper Yo Yo Honey Singh and Pakistani-Dutch rapper Imran Khan combine diasporic and indigenous experiences in musical productions that are consumed in both Pakistan and India, they create a Punjabi identity that renders the divisions of 1947 increasingly faded. Though examples of this are prolific, lyrics from Toronto-based Punjabi rapper Humble The Poet capture the sentiment well. Protesting the frequent identification in Canada of Punjabis with Indians, he asserts the ethnicity’s spread across the two countries. “We 100 million strong and the ‘P’ in Pakistan… Sweet chocolate skin, I’m not Indian / Four knuckles to your eye if you call me that again.”

The resonance with Kasim, who considers fraternity with all diasporic Punjabis, is obvious, and unsettles the nationalist narratives of both India and Pakistan that emphasize irreconcilable difference between Indian and Pakistani Punjabis.

As Kasim’s raps and comments turn increasingly distant from official history, I ask him about the Pakistani-Punjabi relationship. “Has Pakistan treated Punjab well? How has Punjab treated Pakistan?”

I sense him avoiding this politically charged query. “Pakistani borders are patrolled by Punjabis. But we do not assert our identity like Indian Punjabis do.” His hedged response is expected. It is typical of Punjabi cultural revivalists who, understandably, do not want to incur the wrath of the state.

* * *

“Just like cricket, we have made rap our own.” – Xpolymer Dar of the Islamabad-based rap crew, Rap Engineers.

* * *

Although rap has been deeply indigenized and Pakistani rappers learn from each other, they also frequently look abroad for artistic fabric. The rhymes of diasporic South Asians particularly find ears and emulation among Pakistani rappers.

As nations with significant South Asian immigrant populations, American and British governments are not unaware of the influence of the musical productions from their territories. They patronize rap in Pakistan, using it as an opportunity to promote positive views of their countries. They provide Pakistani artists performance venues, and introduce them to South Asian and Muslim hip-hop artists from their countries in hopes of presenting a welcoming face of their governments.

However, many Pakistani rappers hold political views that are deeply rooted in nationalist conversations that are suspicious of such Western overtures. The final article in this series explores the personal, artistic and political negotiations of Pakistani rappers who avail these furnishings.

This article is deeply indebted to Alyssa Ayres’ book, Speaking Like a State, for its discussion of language politics in Pakistan.

2 comments