The following article is written by Laura Fish, a PhD student in Middle Eastern Languages and Cultures and Persian instructor at the University of Texas at Austin. Her dissertation research focuses on the preservation of midcentury Iranian popular films at the time of their production and initial exhibition and their contemporary informal distribution through digital video-sharing platforms.

“Rethinking Iranian Cinema: Aesthetics and Counternarratives” is a film series co-curated by Ajam Media Collective and Cine-Eye, sponsored by the Hagop Kevorkian Center, NYU Iranian Studies Initiative, and the Grey Art Gallery. The first screening takes place on February 19th at 5:30pm at the Cantor Film Center. The article below contains minor spoilers.

Beginning on February 19 and continuing through the spring, Ajam Media Collective and Cine-Eye magazine are collaborating to present the film series “Rethinking Iranian Cinema: Aesthetics and Counternarratives.” With their experimental and art cinema poetics, the films themselves may not challenge typical film festival fare. But as a collection they highlight and quash international audiences’ trained expectations of Iranian films at international film festivals as well as which Iranian films should compose an Iranian film festival in particular.

Beginning on February 19 and continuing through the spring, Ajam Media Collective and Cine-Eye magazine are collaborating to present the film series “Rethinking Iranian Cinema: Aesthetics and Counternarratives.” With their experimental and art cinema poetics, the films themselves may not challenge typical film festival fare. But as a collection they highlight and quash international audiences’ trained expectations of Iranian films at international film festivals as well as which Iranian films should compose an Iranian film festival in particular.

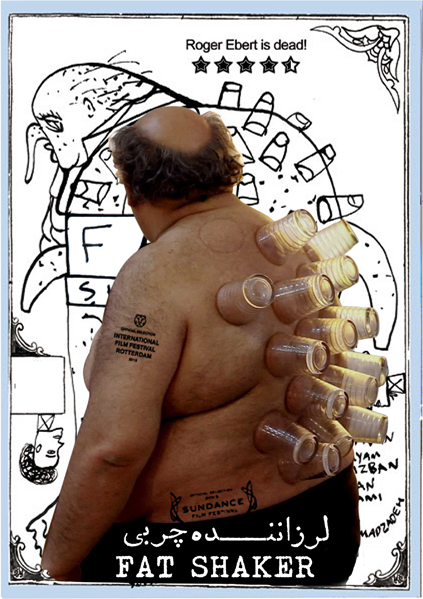

As international investment in and recognition of films labeled “Iranian” has grown within the past three decades, international audiences’ imaginings of what counts as both “Iranian” and “cinema” has shaped our expectations of what we will see at film festivals. However, from viewing three out of the eight films on the schedule, Fat Shaker (2013), Needle (2013), and Slaughterhouse (2015), the “Rethinking Iranian Cinema” series reconsiders how other international film festival selections have privileged the definition of Iranian cinema as an auteur-dominated tradition that produces particular snapshots of Iran and its people without due attention to the methods of storytelling Iranians can create.

For those who do not study the nooks and crannies of all that Iran’s cinematic history has to offer (and even for some who do study it), experiencing Iranian cinema often comes down to name-dropping those Iranian filmmakers with whom international film scenes and festivals are familiar. No other Iranian filmmaker has become more recognizable to international audiences than Abbas Kiarostami, with his flare for sunglasses and teasing apart narrative structures to question the distinction between truth and fiction. The names of Jafar Panahi (The White Balloon, 1995), Majid Majidi (Children of Heaven, 1997), the Makhmalbaf family (Marriage of the Blessed, 1989 & The Apple, 1998), and more recently Asghar Farhadi (A Separation, 2011) spin around festival circuits, correlating “Iranian cinema” with the theory of auteur cinema. This theory has been an analytic tool of industrial cinema studies, particularly from the 1980s, and singles out the work of the filmmaker. By attributing certain formal style and narrative techniques to a filmmaker, cinema can be broken down into author-driven corpuses, rather than focusing on the other collaborators in the filmmaking process, the roles of audiences in interpreting films, or the underlying socio-political and historical contexts that influence a film’s production and consumption.

Audiences understand Iranian cinema as marked by key filmmakers who leave a signature on their film productions through camera style, editing techniques, distinctive narrative structures, social realist critique, and financing measures. As Azadeh Farahmand has noted, domestic financial restrictions have enhanced Iranian filmmakers’ reliance on international festivals, compelling them to appease the expectations of international festivals in order to acquire funding[1] – an issue filmmakers from multiple national backgrounds have been facing, particularly Palestinian filmmakers. Often, external funding requires filmmakers to include the language of the aiding country, or thematically to include images of veiled women and children. The themes, aesthetics, and even languages expected of Iranian art films result in film styles that vary vastly from the commercial genre-driven films that only play in Iranian theaters. Prior to the Islamic Revolution, these popular domestically focused films were romantic melodramas, crime thrillers, and tales of patriotism, while during the Iran-Iraq War, war films dominated, and now comedies and even horror films have found their way to Iranian audiences. But these films have seen little of foreign film festivals.

While more Iranian filmmakers have sought out international attention through festivals, international audiences attending festivals have formed associations or expectations from festival offerings. Regarding which films a festival selects, documentary film scholar Bill Nichols argues that “[i]ndividual films gain value both for their regional distinctiveness and for their universal appeal.”[2] Viewing a film, a festival-goer becomes a “tourist” who encounters difference. Festival viewers expect to engage with difference, and Iranian films “usher us into a world of wind, sand, and dust, of veiled women and stoic men, of unusual temps and foreign rhythms.” From Nichols’s perspective, the festival-goer seeks the exotic but requires an understandable or relatable narrative, otherwise they will feel alienated by too much difference. There is an expectation that the viewer will see and experience “Iran” through what they can see in the film. Narratives revolving around children and gender relations, along with pictures of Iran’s landscape in Tehran or in villages, have found praise amongst international audiences.

In Mohamed Shirvani’s Fat Shaker, the constant close-up shots anchor themselves to the three central characters of the twisted, semi-surrealist plot. While the film moves from street scenes to an apartment and coastal area, it refuses to scrutinize any of these locales in depth. The viewer has no idea where the apartment is or even what space the apartment contains. Instead, the interactions between the stumbling fat, older man, the deaf young man who may or may not be his son, and the mysterious woman whom the man claims to be the boy’s mother, make room for an examination of abusive relationships and social outcasts of a society to which the viewer does not have visual access to understand. The characters appear stuck within the illegally-rented apartment or on the marsh boardwalk as the camera remains in close-up and medium-close-up shots. The obese man, struggling for every breath, seems stuck between reality and fiction, at times knowing who the woman is and at other times confused at her presence and brazen refusal to submit to his bullying. As the large man drinks more alcohol, cigarette packs float, shots proceed without rhyme or reason to subsequent scenes, the camera’s shakiness seems to reveal the alcoholic man’s drunken perspective and disconnect with reality.

Fat Shaker and Slaughterhouse both work to expand viewers’ notions of the boundaries of Iranian film, and Slaughterhouse does so in particular by engaging a community that does not communicate with one another in Persian, but “Rethinking Iranian Cinema”’s addition of Anahita Ghazvinizadeh’s Needle suggests that audiences should consider whether a film needs to address Iran at all. The story of an approaching divorce plays out through the daughter Lilly’s patient attempts to have her ears pierced. Unlike Hamid Naficy’s definition of (Iranian) émigré cinema in “Making Films with an Accent: Iranian Émigré Cinema” (2002), Ghazvinizadeh’s short does not attest to any political concern nor any traumatic relationship with a perceived homeland.[3] Taken on its own, Needle might not be viewed as an Iranian film. By juxtaposing the film with other films by and about Iranians, “Rethinking Iranian Cinema” questions whether authorship still matters in determining a film’s context. The white American girl, who escapes from her parents’ self-centered arguments by playing with a piece of indestructible blue gum, might not speak to any audience as an Iranian tale, or even a universal tale of adolescence. But do the Iranian and Iranian-heritage voices who contributed to the film’s production allow it to fall within the realm of an Iranian project?

In Slaughterhouse, the viewer does not know what drives the young men so willingly sell heroin, nor what the fate of the youngest of them is after he over-doses on the drug. Parents are either absent from the frame, and only heard, or seen as failures, connected directly or tangentially to drug abuse. Needle also reveals the failings of adult characters, both in Lilly’s parents lack of concern for her and in the ear-piercer’s inability to properly pierce Lilly’s ear. The viewer never gets the full picture on her parents’ discord, as the story fixates on Lilly’s perspective overhearing her parents and experiencing their and others’ inattention to her voice.

Although posing vastly differing narratives, what these films draw out stylistically in unison is an attention to visceral experience. Sound plays a key role in all three films as an examination of the quotidian, even when the story itself depicts anything but the ordinary (abuse and attempted suicide, selling drugs and overdosing, and divorce). All three films appear to use improvisational dialogue that emphasizes natural speech. Lilly’s mother pauses in Needle, the boys trip over their words and burst into laughter in Slaughterhouse, and the man mumbles while his son struggles to produce speech in Fat Shaker. Sound effects further emphasize the everyday. The large man in Fat Shaker huffs and puffs with each movement as glass cups used for cupping therapy pop off his back and smash on the floor. The sounds literally voice his struggles and highlight his ill health as his condition and hold on reality disintegrate with each passing scene. The boys’ loud splashing and laughter in the river in Slaughterhouse positions their youth within the forefront of the viewer’s mind as the story grows darker and more tragic. Similarly, Lilly’s mother’s constant phone conversations undergird Lilly’s consciousness, acknowledging children’s cognizance of parental strife from which they cannot escape but to which they must become silenced witnesses.

At the heart of “Rethinking Iranian Cinema”’s selections is an opening for interpretation of what an audience can consider as belonging to the Iranian cinematic milieu through the injection of younger or alternative voices to cinema. Mohamed Shirvani is a seasoned filmmaker who has participated in numerous film festivals and has filmed nine shorts. Fat Shaker marks only his second feature, but its broken narrative and filming style reflect his background in documentary and video art. Behzad Azadi and Anahita Ghazvinizadeh are relative newcomers, both in their twenties, who have received previous critical acclaim for the films that “Rethinking Iranian Cinema” is showcasing. The festival series’ inclusion of young Iranian filmmakers with more established ones privileges neither generation of filmmakers and instead spotlights the multiplicity of stories that Iranian filmmakers can create.

The cinematic stories that “Rethinking Iranian Cinema” includes in its film lineup, like Fat Shaker, Slaughterhouse, and Needle, blast “Iranian cinema” out of the confines of a national cinema that must define “Iranian” through spatially- and linguistically-recognizable means. Instead, the filmmakers whose films have been selected dislocate international audiences’ expectations of Iranianness by attending to stories of often-ignored groups and resisting the cinematic representation of a discernible place. Taken individually, none of these films might be considered Iranian, but as “Rethinking Iranian Cinema” gathers these films together, it persuades its audience to consider the role international film festivals play in shaping opinions regarding what counts as any nation’s “cinema.”

Footnotes

[1] Azadeh Farahmand, “Perspectives on Recent (International Acclaim for) Iranian Cinema,” in New Iranian Cinema: Politics, Representation, and Identity ed. Richard Tapper (London: I.B. Tauris, 2002): 86-87.

[2] Bill Nichols, “Discovering Form, Inferring Meaning: New Cinemas and the Film Festival Circuit,” Film Quarterly 47, no. 3 (1994): 17.

[3] Hamid Naficy, “Making Films with an Accent: Iranian Émigré Cinema” Framework: The Journal of Cinema and Media 43, no. 2 (2002): 16-17.

1 comment