The following is a guest post by Mahdi Ganjavi. Ganjavi is a Ph.D. student at the department of Leadership, Higher and Adult Education in University of Toronto. His essays, reviews, and translations, have appeared in the International Journal of Lifelong Education, Encyclopedia Iranica, BBC Persian, the Bullet, and Radio-Zamaneh.

Awakening from a “Nightmare”

“History is a nightmare from which I am trying to awake,” wrote James Joyce in Ulysses. The US-sponsored Coup of 1953 is such an event: a “nightmare” in Iranian contemporary history. It is widely depicted as a rupture in the modern history of Iran. It is also a Pandora’s box filled with contested narratives. The proliferation of narratives on the coup in recent years clearly shows that it is time for Iranians to awake from “this nightmare,” especially as the Nuclear Deal signals a new phase in Iran-US relations. The following discusses in what sense and to what ends Shahrzad, the most popular Iranian television series of the last year, has contributed to this “awakening.”

The Coup of 1953, planned and sponsored by the CIA, was initiated as the result of United States’ increasing fear of Iran’s possible turn toward communism. It resulted in the toppling of the democratically elected Prime Minister, Dr. Mohammad Mosaddeq. Mosaddeq was the leader of the National Front, an alliance of politicians who shared anti-imperialist sentiments toward Britain and insisted on the nationalization of the oil industry. The National Front advocated limited judicial reforms, and the necessity of confining the authority of Shah to the limits of the Constitution of 1905. It also sought to address the increasing demands of peasants for land redistribution by means of limited tax reforms, forcing landowners to give twenty percent of their surplus to the government, who would then spend it for the good of the village. The nationalization of the oil industry led to an embargo by Britain, which in turn pushed Mosaddeq’s government to completely cut diplomatic and economic relations with the British.

The continuation of the oil crisis and its consequent economic depression, along with the increasing class consciousness of the working class and the peasantry (especially in the northwest of Iran) intensified the class struggle between the traditional ruling class (including Shah, landowners and the clerics), the bourgeoisie, and the proletariat/peasantry. This was a potentially dangerous development for the United States, as it feared that this domestic empowerment of the proletariat/peasantry would result in a foreign tilt toward the Soviet alliance. The intensification of the class struggle also provided the opportunity for the CIA and MI6 to sponsor and plan a coup against Mosaddeq–internally assisted or at least morally supported by the Iran’s ruling class. The post-Coup regime internally framed and systematically eulogized this Coup as the Revolution of the masses in favor of the Shah. Hired mobs played a crucial role in the streets of Tehran on the day of the Coup, creating chaos and attacking several newspapers offices. In Shahrzad, it is the accidental killing of a member of the mob that changes the life of the protagonists.

Moving Forward by Reimagining the Past

In a historical narrative, what is revealed is as important as what is boldly omitted. Shahrzad, a historical series directed by Hassan Fathi set in 1950s Iran, can be seen through this lens. Written by Hassan Fathi and Naghmeh Samini, the first season of this series had 28 episodes and was released from 14 October 2015 to 9 May 2016. The second season is currently being shot, to be released next year. This series, distributed in Iran through a domestic distribution network, is the most expensive production of its kind. The domestic distribution network uses a network of supermarkets and book shops to sell its CD/DVDs. Like any other formal cultural production in Iran, the TV series that are produced for and released through this distribution network are meticulously monitored by governmental censorship organs. It is widely claimed, however, that censorship is less stringent for the domestic distribution network. Shahrzad was so successful that according to the BBC Persian program Pargar, it has become an engine of cultural industry: generating sales of jewelry and commodities inspired by its story and characters. On the exoteric level, Shahrzad narrates a love story between two characters named Shahrzad and Farhad and how it is affected by the Coup of 1953.

Farhad, whose name alludes to the romantic figure of medieval Persian love literature, is a journalist. His father owns a carpet shop in the bazaar. His beloved, Shahrzad, is pursuing her dream of becoming a doctor. Shahrzad’s father has a restaurant in the city. Economically speaking, both Shahrzad and Farhad’s fathers are completely subordinate to a character called Buzurg Aqa, a Godfather-figure who is a big landowner. On the day of the Coup, Farhad accidentally kills a member of the mob that attacks his office. Consequently, Farhad is arrested and condemned to death by the post-Coup government. Although he is granted a pardon, Buzurg Aqa – who is secretly the commander of the mob – forces Shahrzad to marry his son-in-law Qubad. This is the only possible way for Shahrzad to secure the safety of Farhad, and it is also desirable for Buzurg Aqa, as his daughter is unable to bear a child and he seeks an heir to his wealth. As both Farhad and Shahrzad’s fathers are economically and socially subordinate to Buzurg Aqa, they too push Farhad and Shahrzad to separate from each other.

But if one were to look deeper into the historical context of this story, one would discover some bold omissions. According to Shahrzad‘s narrative, the political players in post-Coup Iran were divided into three categories: 1) the sympathizers of Mosaddeq (who was toppled down by the Coup), exemplified by both Shahrzad and especially Farhad; 2) the oppressive ruling class (the Shah, landlords, etc.); and 3) the communist Tudeh Party. These three are pictured in the series as ‘the Good,’ ‘the Bad’ and ‘the Ugly’ respectively. They dominate the narrative’s presentation of historical truth, as they conspicuously omit not only the role of the working class – which is almost always omitted or only depicted if and to the extent that it is under the leadership of the clerics – but also both the religious forces and US imperialist forces are completely eliminated. Not only are there no clerics in the series, but no hero in the movie exhibits any explicit religious convictions either. Most significantly, perhaps, there are no American agents or civilians in the movie. Even though the Coup is attributed to the secret agencies of the United States, its protagonists are heavily depicted as national: the Shah, his court and landowners. So much is clear. But why?

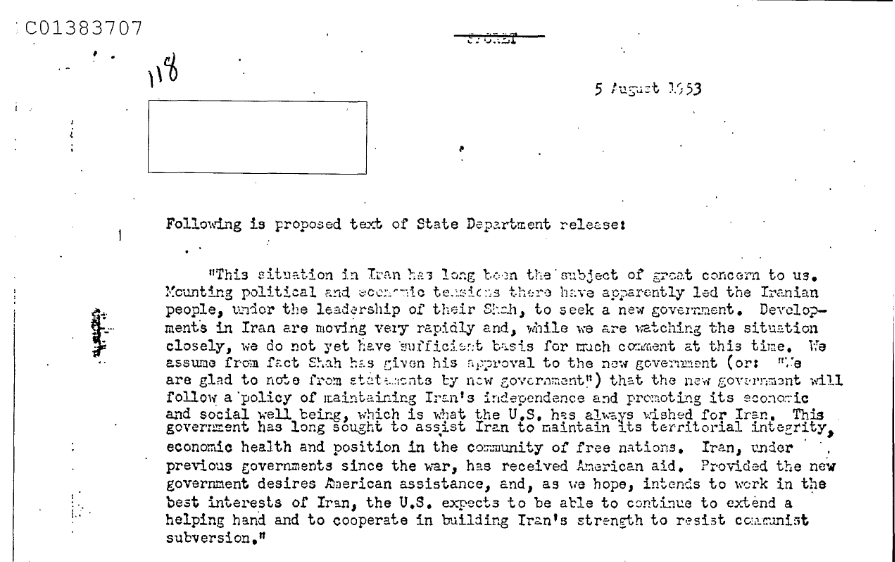

Let us start with the erasure of U.S. forces. The role of U.S. in the Coup is widely known, and the CIA has recently declassified records confirming it. In 2009, President Obama, in a brief account of Iran-U.S. tensions in the past decades, said at Cairo University: “In the middle of the Cold War, the United States played a role in the overthrow of a democratically elected Iranian government. Since the Islamic Revolution, Iran has played a role in acts of hostage-taking and violence against U.S. troops and civilians.” Describing it a “well-known history,” this speech of President Obama was one among a series of reconciliatory gestures for “moving forward.” The election of Rouhani in 2013 was a sign that this shift–the possibility to move forward–did not have only advocates in United States, but also in Iran.

This process of moving forward requires a more concrete knowledge of the social and political history that resulted in the Coup, but almost all previous post-revolution dramas and narratives have stressed the decisive role of imperialist forces, even to the extent of neglecting or downplaying domestic agency altogether. All of them have narrated this Coup in such an ahistorical setting that in the absence of any concrete social and economic relations, it is the imperialist forces that have the final say.

Historically speaking, Shahrzad ought to be contextualized in such political and historical developments, both internally and internationally, and should be read as a response to these calls. In this sense, it is an effort to “move forward” through fading out the role of the US in the post-Coup economic and social relations. The desire to forge stronger ties with the US in the post-nuclear deal Iran is perhaps an explanation for why US nationals are mainly absent as the antagonists of Shahrzad’s narrative. But this fading out is not accompanied by a more concrete narration of the social and economic relations and the class struggle before and after the Revolution. Instead it is accompanied with a second more provoking elimination: there is no religious front in this historical account.

More than glorifying Mosaddeq (the leader of the National Front), Shahrzad is purging Ayatollah Kashani (the spiritual leader of Fada’iyan Islam) in its historical account. Ayatollah Kashani was the most powerful political cleric of his time, who shared anti-imperialist sentiments with Mosaddeq and became the head of the parliament for a period of time during Mosaddeq’s government. However as history unfolded, the alliance of the National Front and Kashaani became a fragile one, as Kashaani withdrew his support of Mosaddeq during the Coup, and–as several historians suggest–most probably even assisted the Coup. Buzurg Aqa’s authority over the mobs in the series functions as a depiction of Kashani in disguise.

As for the omission of clerics from the narrative, one should consider the ideological historiography of the Islamic Republic. Although the official historiography of Islamic Republic has changed during time to cover some issues and put aside others, it still has been very insistent and consistent when it comes to certain subjects. From the standpoint of official historiography, no official cultural product of Iran can glorify the nationalist forces (historically exemplified in Mosaddeq and the National Front) while and if the alternative of the religious front is available. Put differently, the Good in a historical account can only be the religious front; other groups shall be overshadowed by it. This is clearly the case when it comes to the revolution of 1979, or when it comes to depicting the student movement of 1970s. This historiography even goes back to rearticulate the religious sentiments of medieval Persia as quests for creating an ideal society which centuries later was established by Ayatollah Khomeini. For just one example of such ideological rearticulation of the past, I can point to Jalal Al-Din, a series which narrates the first few years of the life of famous medieval poet Rumi. In this series, the father of Rumi advocates exactly a system of governance that can be seen today in the Islamic Republic.

The Past is Never Dead

Unlike these previous TV series, Shahrzad glorifies nationalist forces. Not only are followers or sympathizers of the National Front its protagonists, but the erasure of all the Leftist sympathizers who were killed after the Coup effectively renders Hossein Fatemi (the foreign minister of Mosaddeq’s government) as the only “martyr” of the coup. In this sense, the historiography of this series can be seen as an Islamic bourgeois historiography in its clash of interests with the revolutionary historiography of the Islamic Republic. Both of these historiographies are still part of the official historiography of Islamic Republic, but they appeal to a certain range of audiences. At different times, different aspects are emphasized or highlighted in cultural productions depending on specific political/economic demands. For instance, the Islamic bourgeois historiography is more able to attract a young and urban middle class as sometimes it blurs the religious messages and instead emphasizes a nationalist discourse; a discourse which in turn would willingly be incorporated by several conservative circles with deep roots in the military forces.

This series, as an example of Islamic bourgeois historiography, clearly reveals the ways in which the historiography of the Islamic bourgeoisie is different from and similar to the dominant “revolutionary” historiography. Both dismiss Leftist groups as subordinates to the Soviet Union, thereby fully negating not only their, but also any contribution by the working class to the cause of the nationalization of the oil industry; both share hatred toward the Shah and his court. Yet, while the dominant “revolutionary” ideology is afraid of nationalistic views (exemplified in the National Front) and finds them beneficial only seasonally, such as during an economic crisis, the bourgeois class finds them beneficial for economics in all seasons.

Faulkner’s famous quote, “the past is never dead. It is not even past,” applies very much to the Coup and its contested narratives. Shahrzad is another example which shows that present political and economic aspirations, desires, and interests are constantly changing what had happened in the past. It shows that not only the present or future, but also the past is a site of constant political struggle. Therefore, any effort to “move forward” redefines the past, only to confine it in a new temporary beneficial frame.

2 comments