The following is a guest post by Arafat A. Razzaque, a PhD candidate in History & Middle Eastern Studies at Harvard University. He specializes in medieval Islamic social and cultural history, and has a secondary interest in the Thousand and One Nights, stories from which he first read in Bengali translation.

This article is the first of a two-part series about Aladdin. Part two, entitled “Who wrote Aladdin? The Forgotten Syrian Storyteller,” can be found here.

***

The recent clamor around Disney’s forthcoming remake of Aladdin (1992) was a vivid reminder that an entire generation of people today grew up enchanted by the film. Rumors about the studio’s alleged difficulty finding an actor to play Aladdin sparked renewed criticism of Hollywood’s diversity problem. The comedian Hari Kondabolu responded on Twitter: “Lots of brown kids got called Aladdin growing up. Now you…don’t want to cast one of us?”

Others pointed to India’s vast pool of actors who can sing and dance, being part of the world’s largest film industry producing between 1,500 to 2,000 movies per year in nearly two dozen languages. Of course, Aladdin and the larger collection of stories known as the Thousand and One Nights (Arabic: Alf layla wa layla) are ingrained in South Asian pop-culture.

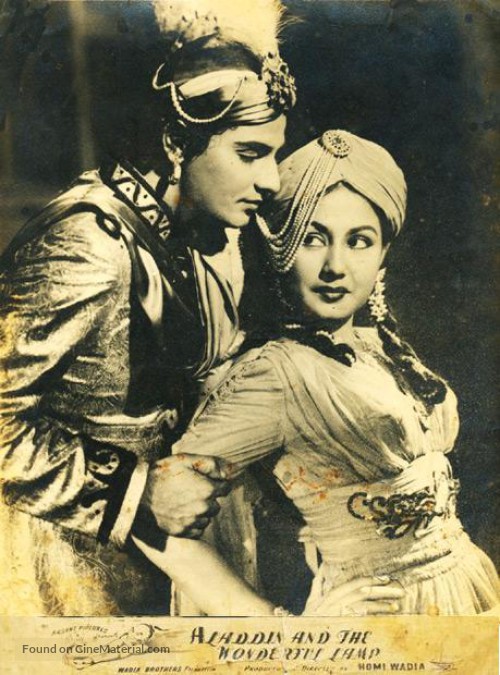

Numerous film adaptations of the Nights have been made in India since at least 1905, including the two early Aladdin movies of the silent era by B.P. Mishra (1927) and J.J. Madan (1931). Like Madan, another Parsi filmmaker Homi Wadia directed the 1950s superhits Aladdin (1952) and Ali Baba (1954).

Responding to the news about Disney’s Aladdin, many on social media began circulating photos of their favored Bollywood celebrities. However, others protested that it would be wrong to cast an Indian actor for a Middle Eastern role. This generated further confusion, as those who have read the original story pointed out that it actually takes place in China.

Some were still not dissuaded, even citing the movie’s opening song “Arabian Nights” as proof of its setting. Disney’s official casting announcement failed to abate the controversy, and some remain unhappy that Princess Jasmine will be played not by an Arab but a British actress of part-Indian heritage.

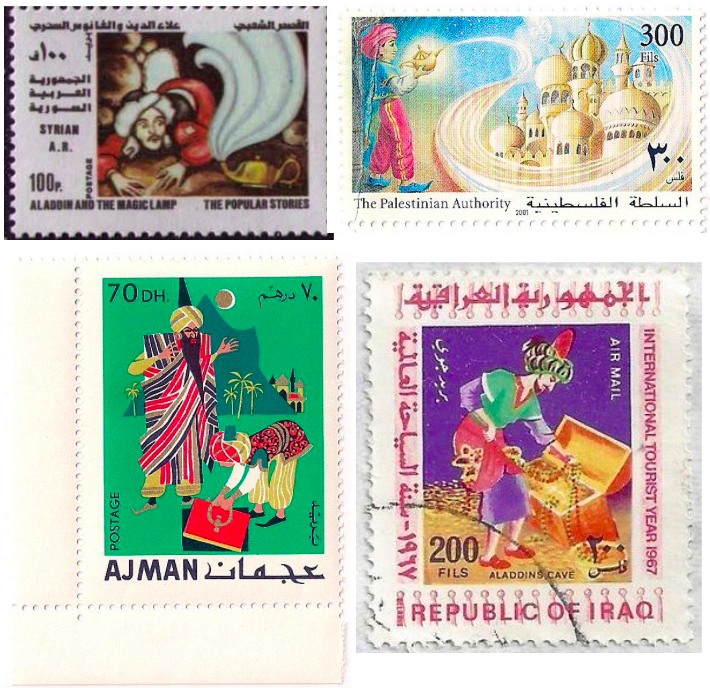

These debates are nothing new to the 1001 Nights, regarded as one of the most popular literary phenomena in the modern world. Scholars have long used these stories to critically analyze concepts like authenticity and cultural appropriation. Their insights are hardly limited to specialist circles, as several voices on the internet recently pointed out that Aladdin was not part of the original Arabic before the eighteenth-century French “translation” by Antoine Galland. The implication is that the story is a Western Orientalist creation, a mashup of stereotype and fantasy set in “one of the kingdoms” of China visited by an “African magician.”

But the issue is far more complicated. Galland himself actually learned the story from a Maronite Syrian from Aleppo named Ḥannā Diyāb. From the text of Aladdin as published by Galland in 1712, we cannot easily tell how much of it was the Frenchman’s own invention. The backstory behind this well-known story is truly a convoluted saga that confounds our notion of origins.

As far as China

The Chinese setting of Aladdin seems to surprise many today. But even this in itself is quite plausible in the 1001 Nights imaginary, and we need only look at the very opening of the frame tale of Shahrazad and Shahriyar: “Long ago, during the time of the Sassanid dynasty, in the peninsula of India and China were two kings who were brothers.” While his younger brother rules in Samarqand, Shahriyar is said to be king of India and China. Thus, although she has a Persian name and many of the stories she tells are set in Cairo and Baghdad, Shahrazad herself is situated not in the Middle East but farther east, somewhere in or around India.

The Far East is similarly linked together with South Asia in the remarkable tenth-century Arabic travelogue, Accounts of China and India by Abū Zayd al-Sīrāfī. Islam and China were never entirely separate worlds, whether due to earlier Muslim contacts with the distant Tang empire, or because of the powerful Mongol legacy that united Persia and China in the late-medieval period.

Today, ten of the 56 recognized ethnic groups in the People’s Republic of China are predominantly Muslim, inhabiting mostly the western provinces. Many readers have therefore interpreted Aladdin as referring to the Turkestan region of Central Asia, what used to be known in Europe as Great Tartary.

But in early Arabic usage, China was often just a symbol for a faraway land, as in the famous saying attributed to the Prophet: “Seek knowledge even as far as China.” It is in this sense of an abstract, exotic place that China tends to appear in the Nights. The Hunchback’s Tale, for example, is also set in China and features a tailor and his wife, just like Aladdin’s parents.

The geographic setting of Aladdin drives the plot only insofar as the evil magician takes away the princess and Aladdin’s palace to Africa. When Aladdin comes to rescue her and the princess is trying to entrap the sorcerer with a potion, there is even an odd conversation on the merits of Chinese versus African wine. Interestingly, Arabic versions of Aladdin denote the sorcerer as a “maghribi” or North African, which sometimes led to pedantic commentary by Victorian translators like the poet John Payne, famous for his translations of Hafiz.

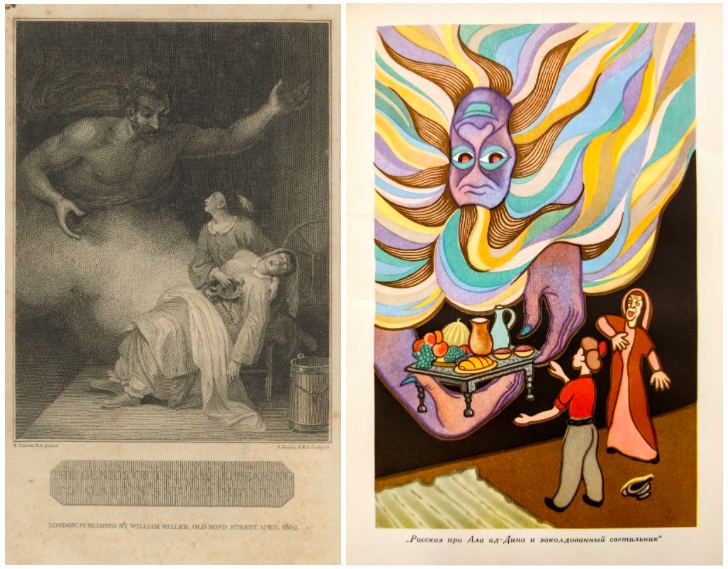

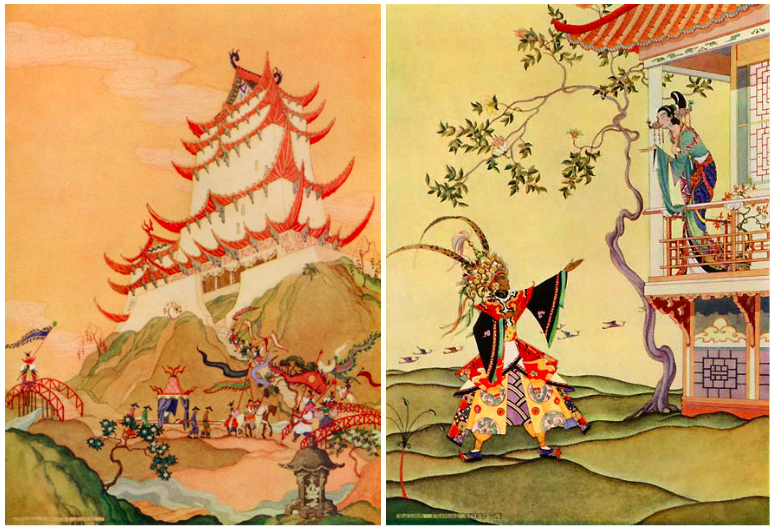

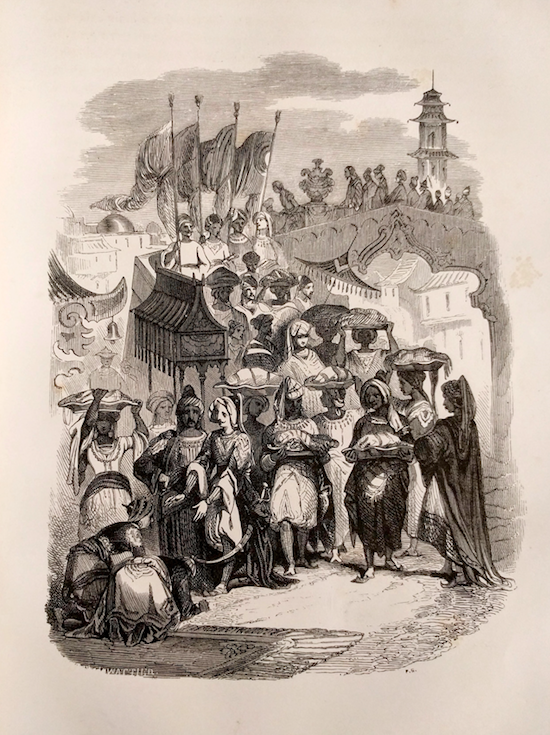

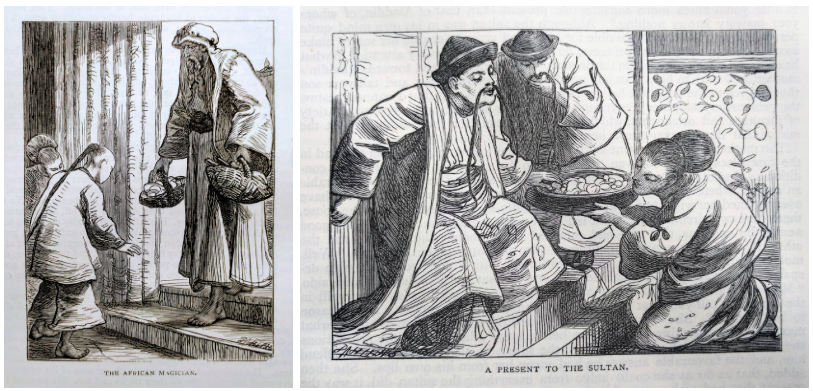

If the textual Aladdin was of unspecified ethnicity living in an abstract Far East, he nevertheless acquired a distinct Chinese typology in European visual representations. In a desire for “authentic” rendering, book illustrations from the Victorian period typically portrayed Aladdin with the Manchurian hairstyle of the Qing era, with a shaved forehead and a long queue.

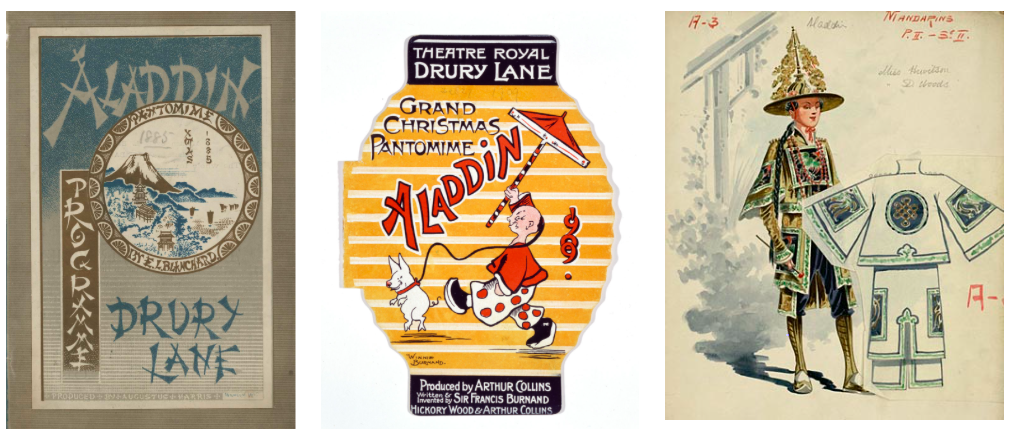

Global trade and the craze for Chinoiserie in early modern Europe also turned the story’s setting into a mirror for contemporary projections. In his pioneering dramatic adaptation of Aladdin first staged at Covent Garden in 1788, the Irish playwright John O’Keefe included a sarcastic song urging the English to give up imported china and “buy local” instead.

Aladdin has had a long life on the British stage, adapted into countless versions of the burlesque musical comedies known as pantomime (“panto”) and still produced today. The story was often set in Peking, and other details acquired concrete if hybrid form in the stock characters typical of pantos. Based on his father Mustafa, Aladdin’s unnamed mother became “Ching Mustapha” in an 1813 production.

Morphing through numerous figures over the decades, since 1861 she became the iconic dame “Widow Twankey,” a laundress in drag whose name refers to a brand of Chinese tea originating in Tunxi. The nineteenth century, after all, was exactly the period when tea-drinking became integral to British culture.

While they often dealt in problematic stereotypes, pantos were self-conscious jumbles. An anonymous 1879 play script for Sinbad the Sailor declares in the byline: “Written, re-written, adapted, translated, fabricated, invented, arranged and composed.”

Playwrights seemingly had free rein even as they relied on conventions. Aladdin had become so established as Chinese in British theatre, that it influenced other creations like Chu Chin Chow (1916), a record-breaking success based on the story of Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves.

From Baghdad to Agrabah

But looking back from the Disney film, the Chinese Aladdin of the pantos is almost unrecognizable. This is partly due to a distinct Hollywood tradition, where Arabian Nights material goes back to its earliest days. Even more than the original story or the many preceding Aladdin films, the most direct inspiration for Disney was The Thief of Baghdad (1940), Alexander Korda’s Oscar-winning British remake of the 1924 silent of the same name. Disney’s animation is basically a remake of Korda’s technicolor classic, transforming Aladdin into a clever kleptomaniac and reinventing the characters of Abu and Jaffar. Apparently, Disney’s Aladdin was also meant to be set in Baghdad. But as the US was bombing Iraq during the First Gulf War just when the film was in production, Disney changed the setting to a fictional city to avoid awkward associations with the Baghdad of Saddam Hussein.

Regardless, Disney’s retelling of the story effectively links Aladdin to the Middle East, although the original setting is implicitly acknowledged when his flying carpet adventure with Jasmine culminates at a festival in China. That Disney’s “Arabian” fantasy and its revival of some old Hollywood caricatures coincided with a major American military intervention in the region was a charged irony not lost to media critics. In response to Arab-American activists including the late Jack Shaheen, who just passed away last month, Disney was compelled to change a few of the lyrics in Aladdin after the film’s release.

Interestingly, while many viewers have now embraced Aladdin and Jasmine as “Arab” characters, Disney was hardly attempting any semblance of geographic coherence. The royal palace seems to resemble the Taj Mahal in Agra, India. Background scenes are also said to have been based on Persian miniatures and Victorian-era Orientalist illustrations, as well as photos of Isfahan taken by the film’s layout supervisor Rasoul Azadani, an Iranian animator at Disney and namesake of Razoul, Agrabah’s captain of the guards.

Beyond the West

Whatever its sources, Disney’s visual codes have widespread influence. This can be seen in recent children’s cartoons in Korean and Vietnamese, which combine elements of the original Aladdin with characters from the Disney version. A similarly hybrid flash animation is seen in a Bengali version from Wings Animation Studio in India, which makes fairy-tale cartoons available online in 19 different international languages as well as a dozen Indian languages. An unusually faithful adaptation of the story appears in a flash animation series in English and Chinese produced by Little Fox, a language education company based in Korea. But this Aladdin is set in an unnamed “faraway land.” Shahrazad narrates the story from what looks like the Umayyad Mosque of Damascus, while identifying herself as “the wife of the king of Persia.”

Despite its corporate-driven multi-billion dollar culture industry, Disney cannot entirely dominate the global representation of fairy tales. A major alternative visual tradition exists in Japanese manga, which often draws on folk tales both Asian and European. The popular anime series from from 1976–79, Manga Sekai Mukashi Banashi (Manga Fairy Tales of the World), was dubbed by a Kuwaiti studio as Ḥikāyat ʿĀlamīya or “International Tales.” The Arabic broadcast made the the Aladdin cartoon its first episode, describing it as “a tale from Arab tradition” (al-turāth al-ʿarabi). The setting remains unstated, but it is a visually Islamicate world while the sorcerer is represented as a dark figure in Arab costume.

A dramatized but faithful telling of Aladdin appears in another Japanese animation from Toei, part of the 1994 series Anime sekai no dôwa (broadcast throughout Europe, including in Polish and Greek). It was dubbed into Arabic by a Syrian company specializing on Japanese anime and aired on Spacetoon, a Middle Eastern competitor to Cartoon Network.

Live-action versions of Aladdin reflect similarly diverse adaptations. A recent Swahili film, Aladini na Taa ya Ajabu, appears to be set in a contemporary village in Tanzania, but prominently depicts Aladdin’s father as a tailor. Between 2007–2009, the Indian channel Zee TV aired a serial called Aladdin, which ran for 183 episodes. Similar to popular adaptations of ancient Indian epics like the Ramayana, Zee TV’s Aladdin adopts a largely South Asian idiom, such as Rajput or Mughal costumes. But the story is set in the fictional “Zarniabad” and reflects the influence of Disney in the names given to the princess Jasmine and the Jadukar (“magician”) Jafar. The show’s Indian casting did not prevent its appeal in the Middle East, where it has been broadcast in a dubbed Arabic version.

The tradition of portraying Aladdin as Chinese is still alive if barely, and was last seen in the lavish two-part miniseries Arabian Nights (2000), a joint British/American production. Creative but also faithful to the text, this version reverts to a Victorian obsession with authentic representation. The magician speaks with a strong West African accent, and the setting is overtly Chinese: in fact, the cave with the lamp is now guarded by an underground terracotta army! The royal court and the princess, here called Zobeide, are depicted in the sumptuous colors of the Qing Dynasty. But the film is a real surprise for viewers now accustomed only to an assumed Middle Eastern story, as in one online comment: “since when was Aladdin ever Chinese? LOL.”

The Stakes of Authenticity

The nineteenth-century British Orientalist Richard Burton famously derided all previous translators of the Nights for creating “a bastard Europeo-Oriental, pseudo-Eastern world of Western marionettes garbed in the gear which Asiatic are (or were) supposed to wear.” He clearly had a point, and this description seems oddly fitting of the evolution of Aladdin over the past two centuries. (Prof. Michael Cooperson makes this argument in his 1994 paper on “The Monstrous Births of Aladdin”).

But what motivated Burton was an interest in finding the true essence of the East, to be distilled from arcane Arabic and Sanskrit texts. This was no different in spirit from Victorian artists trying to make Aladdin look as “Chinese” as possible.

In other words, the racial logic of representation was itself also a function of Orientalism. In response to Western discourses of the Other today, resorting to ethnic nationalism or essentialist assumptions about cultural identity would be to miss the moral of this story altogether. For one thing, it would be a dismissal of the non-Western world’s own rich traditions of cosmopolitanism, as exemplified by the real and imaginative threads connecting the Middle East and East Asia in the 1001 Nights.

11 comments

Ever since the announcement by Disney of a new live-action adaptation, I’ve been investigating the story’s origins as much as possible.

I’ve became ncreasingly frustrated that in all my reading I’ve seen a lot of criticism of how world media has mishandled adaptation. I’ve not seen any positive advice and guidance about how to do better, to be respectful and attentive, if there’s discomfort with the concept of “authenticity.”

I’ve also been reading about Plato’s Atlantis and The Lord of the Rings and the inspiration they took from real-world history and places to inspire credibility in their audiences, especially by the use of an unnecessary degree of detail in describing these creations of imagination.

So, if I had the talent to craft an cinematic adaptation, I’d include details about the setting in an exotic, spectacular ideal city in “China”, from the the Arab/Persian perspectives on the liminal zone of Central Asia, especially Samarkand and Bukhara in Transoxiana. Imaginary doesn’t mean unrooted in real-life. I would recommend it as part of the mix.

That, of course, just one aspect of the process, but one I’ve focused on.

But my point is, don’t just discuss what you don’t like about the metamorphosis from folktale to dramatization, state either in general or with exactitude what you want to see instead.

This is a pretty comprehensive essay – however the omission of Richard Williams’ ‘The Thief and the Cobbler’ is unforgivable, but perhaps can be excused to a degree as it was never completed and released – but is available on the file sharing networks and perhaps other sources as a ‘recoiled’ cut.