The following is a guest post by Khodadad Rezakhani, a historian of Late Antique Iran and Central Asia at Princeton University.

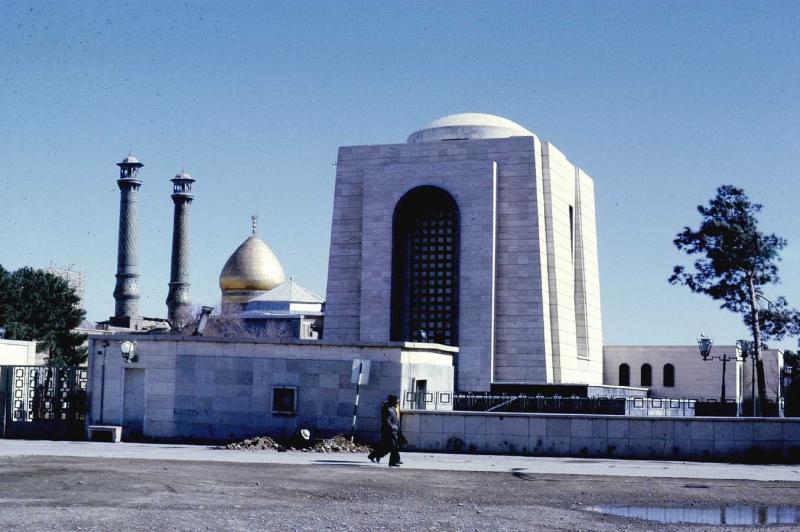

Iranian cyberspace is currently abuzz with the news of the discovery of the mummy of Reza Shah (1925-1941) the penultimate king of Iran and the father of Mohammad Reza Shah who was deposed in the 1979 Revolution. The body was discovered during a project expanding the premises of Shah Abdol Azeem, a popular religious site south of Tehran. The project was taking place in the former Mausoleum of Reza Shah, where his mummified body was reburied after his death in exile in Johannesburg in 1944.

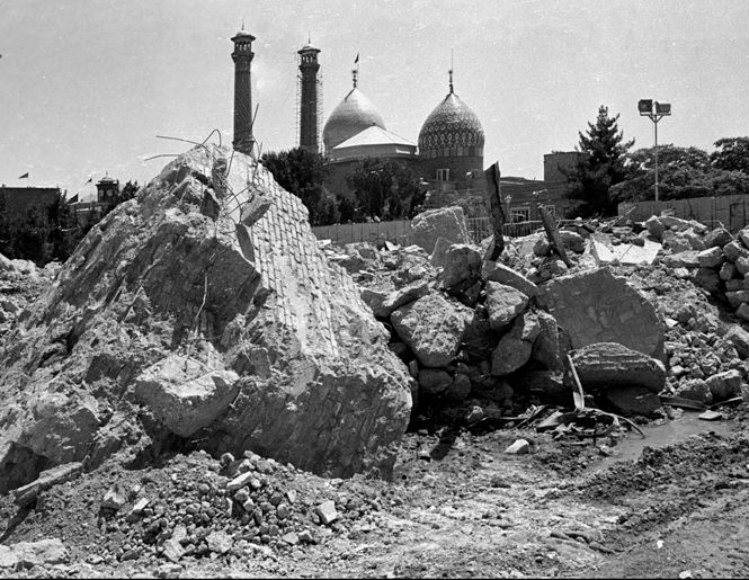

Part of the reason why this story has gotten so much attention is because it involves Sadeq Khalkhali, the firebrand judge of the early Revolutionary Courts who was widely known as the “hanging judge” because he so often ordered the execution of those tried in his courts. In 1979, he led the destruction of Reza Shah’s mausoleum and tried to dig out his body as well. He demolished the building, but was unable to find the body. Khalkhali said that his failure was probably because Mohammad Reza Shah, before leaving the country in January 1979, had exhumed his father’s body and taken it with himself – though this is strenuously denied by the late Shah’s family. Despite the lack of official confirmation so far, the mummy seems to be the body of the dead Reza Shah – and this has resurrected the Khalkhali story as well. The judge who sentenced Amir-Abbas Hoveyda, the powerful Pahlavi prime minister, to death and reportedly fired the shots himself, seems to have been proven a liar.

The discovery of the mummy has trigged a wave of attention and speculation that all point to one fact: Reza Shah is a divisive figure. For giddy nationalists and those longing for the “prestige” of the Pahlavi-era Iran, he is the father of Iranian modernization, the man who ordered the building of modern roads, trains, cities, and changed even the dress code – he banned traditional Iranian clothes and replaced them with a strictly European dress code that removed the equivalent of the Indian kurta or Arabic dishdasha.

For the 1979 Revolutionaries, he is the evil founder of Iranian Westernization and the destroyer of traditionalism and religious society, the man who pulled hijab from the heads of women (through a law banning the veil in the 1930s) and forced Iranians to lose their namoos (sense of honour, propriety and social norms). For many intellectuals, he is the person who caused a break, a cesura, in Iranian history by importing Western industrialization and its related mores and brutally suppressed any voice of dissent. Another view is that Reza Shah, through his complete dismissal of what was considered the “tradition”, and his authoritarian importation of Western modernity, also destroyed a well established sense of communal-national identity, replacing it with an ill-conceived and incomplete, ancient-oriented nation-state.

But the memory of many of these feelings are becoming pale, mostly as a reaction to the current political realities. For many Iranians today the emphasis on modern Iran’s ancient Persian identity that Reza Shah promoted is by now second nature – for better or worse. Reza Shah’s act of forcefully removing the hijab from the heads of the women of his time, put in the context of the unforgiving policies of the Islamic Republic forcing the hijab on the descendants of the same women, is now seen as a progressive act by some (comparable, for example, to Peter the Great cutting the beards of his boyar nobles).

In a land obsessed with engineers and engineering, Reza Shah’s authoritarian industrialization is now viewed by some as the only sensible way of progressing Iran’s economy. Even more, with the growing dissatisfaction with the current government of Iran, the Pahlavis and their founder Reza Shah are now enjoying a new-found support and nostalgia. The Pahlavi dynasty’s use of an ancient-oriented program to create a modern identity has found much support as an antithesis to the Islamic Republic and “Islamism” in the current climate of Islamophobia that has become prevalent in many societies.

Carparks and Rubble

But what does all this have to do with the bodies of dead kings? Much like finding the body of British monarch Richard III in a carpark in 2012, one expects that the discovery of the mummy of a king in the rubble of his mausoleum would be a matter of historical curiosity. But in a society filled to the brim with political opinion and feeling very much part of history, the body of the Father of Modern Iran is not just a body. Reza Shah is seen by many as a modern-day saviour, much like the chosen ancestor himself, the Pahlavi designated “founder” of the 2500 year old Empire of Iran, Cyrus the Great. Like Cyrus, he carries the epithet of Kabeer or Bozorg, “the Great” – in the title “Reza Shah Kabeer”. In the minds of some of his supporters, the comparison goes even further, like Israeli-Iranian commentator Meir Javedanfar who even credited him with saving Iran’s Jews – much like Cyrus the Great. He is seen as the unifier of the country who gave rights to the minorities, perceived to be without any rights before.

But despite all the praise, the surprising fact – after ignoring all the noise – is that there has been no clear official reaction to this event yet. The discovery has prompted people to praise Reza Shah and recount his contributions – but this is already a mainstay of Iranian national debate.

Some recount the Khalkhali story and are happy that the executioner-judge has received another blow, even after his death (and from another dead man). A few are using the occasion to again point out the age-old adage of how bad the Qajar Dynasty (1796-1925) was and how Reza Shah saved Iran from their incompetent grip. This is yet another seemingly unchanging narrative, itself a Pahlavi one, which is repeated whether a mummified body is present or not. But no one yet knows how to react to the news itself and what it means.

We have just seen a picture, an unidentified selfie, and no clear statements from any authorities. The authorities themselves probably don’t know what they are doing or how they react, as the discovery seems to have been made by the semi-autonomous organization that runs the shrine of Shah Abdol Azeem, and not by any governmental agency. In Iran’s current political climate (the December 2017 protests, the anti-Hijab demonstrations, the sudden drop in the currency value, the Syria war, and most importantly the JCPOA and its fate and the “War Cabinet” of Donald Trump), the mummified body of a dead king is hotter than a hot potato, and no one really wants to hold that potato for too long. The head of Tehran’s cultural heritage agency has declared that the body, to whomever it might belong, is a cultural asset.

A few other people have denied there really is even a body. No one has yet explained the pictures or the whereabouts of the body at present. On social media, some speculate that the government’ may plan to destroy the body and hope that this does not happen. As things progress, it is becoming evident that the body is real, and someone needs to do something with it. Putting it in a museum like Jeremy Bentham – the English philosopher who is mummified and on display in the main hall of University College London (UCL) in London – would be against everything that the Islamic Republic stands for, as it has done all it can to wipe away all memories of the Pahlavi era.

Burying it is the likely scenario, but where do you bury such figure? In his mausoleum? Would you rebuild the mausoleum after 40 years and re-sanctify the site, like Richard III’s carpark? Or would one just bury him in Behesht-e Zahra (Tehran’s main cemetery) like the rest of the dead? What would one write on his gravestone? Reza Shah the Great? Unlikely, and a dangerous move, risking the reaction of the hardcore conservatives and their cronies. Simply, Reza Pahlavi, with no mention of who he was? That will get many people going and probably would give the best excuse to the monarchists and their recently reinvigorated claims to solidify support. Reza Shah, in his death, is more a symbol of how Iranians would like to see their past, recent or ancient, than any other ruler of the country.

Mummies across Tehran

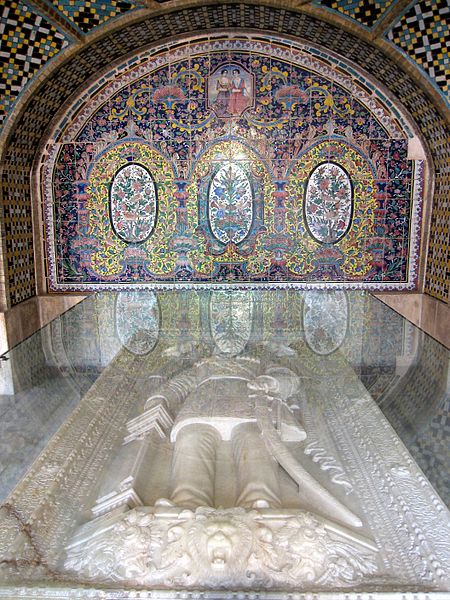

It is important to consider how the bodies of the dead and the ceremonies associated with them in Iran in general are relevant in this case, both in a historical and contemporary sense. A very similar case to that of Reza Shah is the body of Nassereddin Shah Qajar (1848-1896) who is buried in the same shrine of Shah Abdol Azeem. Assassinated in 1896 while visiting the grave of his beloved consort Jayran, Nassereddin Shah was buried close to the location of his assassination and next to his wife. The grave was adorned with a magnificent stone and was quite prominently displayed to the pilgrims of Shah Abdol Azeem. However, the Revolutionaries of 1979, similar to the group who destroyed Reza Shah’s mausoleum, also broke the gravestone of Nassereddin Shah and his wife (the remains are kept in the Golestan Palace museum in Tehran) and the graves themselves were covered, with a drainage hole now built on the site of the graves (no one really knows if there were any bodies or bones recovered). This is, as explained by the local custodian, a way of showing that “we [the religious custodians] don’t care about kings and princes.”

At the same time, the site of Shah Abdol Azeem itself is the mausoleum of an early Islamic saint, protecting his remains and acting as one of the most important pilgrimage sites in Tehran. In fact, Tehran alone boasts of more than 100 imamzadehs (mausoleums of descendants of Shi’a imams) and other holy pilgrimage sites (including Sar-e Ghabr-e Agha, the mausoleum of Nassereddin Shah’s son-in-law and Tehran’s prayer leader in the late 19th century!).

Aside from historical figures, the burial of the martyrs of the Iran-Iraq War, whether during the war or since forms an important form of state-sponsored public ceremony. Great processions from large mosques toward the special Martyr’s Bloc of the large graveyard of Behesht-e Zahra, often with much media coverage, are a reminder of the war period and form part of the government’s ideology of struggle against the powers who would wish to destroy the Revolution and its values. On the other hand, the bodies of those considered unacceptable for the values of the revolution and the Islamic Republic, including executed political opponents, are often buried without any ceremony and during the night by the security forces, only letting the families know of their whereabouts after the burial has already taken place.

The manner in which the body of a dead king is treated, particularly after it was sought in vain by the early Revolutionaries, is of much importance. Whatever those responsible do – whether they bury it secretly like the political opponents, or allow for a normal funeral like the bodies of the war martyrs, or even allow a larger ceremony (very unlikely) – their actions will be closely observed, and perhaps deemed wrong in any case. In a society where death and the bodies of the dead form such an important means of public engagement, the position of someone charged with burying a mummified dead king is not enviable.

1 comment

Wow! What an incredible article! I wish I had something more eloquent to add (lol) but I just think this article is super well written. The way the author links the Shah’s mummy with the ambitions of the Pahlavis to reshape Iran’s national identity is really striking, especially when juxtaposed with the imamzadeh across the city. A great read!