The following piece was written by Mariana Irby, a PhD student in Anthropology at the University of Pennsylvania. Her research focuses on nationalism, gender, and post-socialism in Tajikistan and Tajik migrant communities in Russia.

Since 2015, the government of Tajikistan has enacted various pieces of legislation that discourage or outright prohibit hijabs, burqas, and other types of so-called “Islamic” or “foreign” dress. Such restrictions target women across spheres of work and in the general public, and even form the basis of a 367-page government-issued guidebook on “recommended outfits.” In addition, they specifically encourage women to wear Tajik national dress or libosi milli, sentiments echoed by President Emomali Rahmon in a state address.

Though often loosely enforced, these laws have proved discursively salient, reigniting century-long debates and anxieties regarding the parameters of feminine modernity. From the bazaar to the kitchen courtyard, rehashed insecurities resurface about the ideal Tajik woman and exactly how much fabric she should wear on her head.

Outside observers have characterized these measures as merely new iterations of long-standing government crackdowns on Islamic expression that exist in Tajikistan and other former Soviet republics, where threat of Islamic radicalism, real or imagined, has proved a very useful justification for these new states’ authoritarian measures at suppressing political opposition. Measures to restrict “Muslim” sounding names, age limits for entering mosques, and crackdowns on beards also form part of these trends in Tajikistan, where 98% of the population identifies as Muslim either as a religious or cultural marker.

But for all the media attention on what is “Islamic” or “anti-Islamic” about the policing of women’s sartorial practices, observers have devoted far less attention to the promotion of the “national.” How does one embody the interests of the “nation” through modes of dress?

Tajikistan’s history of independent nation statehood embarked following the collapse of the USSR in 1991. The abrupt transition from state socialism to market capitalism thrust Tajikistan head-on into neoliberal “global” modernity. Since the beginning of the 21st century, extremely high rates of outbound labor migration have characterized Tajik post-socialist existence. Therefore, one must locate the drive to conceptualize and enforce a national dress within these parameters.

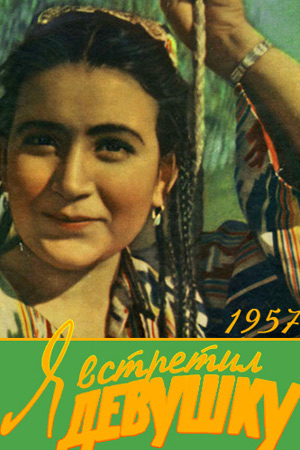

Often eye-catching and highly personalized, self-consciously “national” clothing or libosi milli adorn the bodies of a majority of Tajik women across age, social class, and ethno-geographical groupings in Tajikistan. These garments, broadly defined, feature a tunic (kurta) and a loose pair of pants (shalvor). A kerchief tied at the nape of the neck (rumol) is also often worn. Typically, women buy fabrics at local bazaars and employ a Tajik seamstress or duzanda to sew these materials into this customized yet “traditional” fashion.

But many elements of these “traditional” garments are new, such as the fabrics and sequins imported from neighboring China from which they are often made as well as the circumstances under which women wear them.

Late Imperial Russian and Soviet notions about national identity and representative material culture have largely shaped understandings of Tajik national dress. The promotion of a distinct, recognizable form of dress for each republic was one way that the Soviet Union navigated the competing demands of both allotting space for national self-determination and promoting Russification as an avenue for modernity and interethnic harmony.

Today, though libosi milli tends to exhibit certain prints and features thought to be timelessly Tajik, the national character has as much to do with the symbolic forms of engagement and context than substance. Leopard-print or bedazzled pink fabrics also figure into notions of contemporary libosi milli, as long as these garments are of the correct cut and style.

What is especially interesting in the contemporary period is the spatially-divided gender bifurcation that characterizes Tajikistan today and the fact that there seems to be more pressure on Tajik women today to dress in a distinctly, self-consciously “national” way than during Soviet times, when a more ethnically diverse population and a different context of statehood and aspirations for modernity existed.

Lola, a student in Dushanbe who preferred self-described “Western” or “European” styles, pointed to generational inconsistencies in the valorization of libosi milli. “I guess I sometimes do get disapproving remarks from older relatives, like “that dress would look so much better over a pair of shalvor.” But then I’ll sometimes just respond to them by saying “ama-jon [auntie], you wore bell-bottoms in the USSR…”

While Tajik women in the late 20th century, particularly in urban areas, often embraced universalist Soviet ideas about the uniting potential of modernity, today a distinctly local feminine modernity has become part of the overriding national discourse.

In the last three decades following independence, Tajikistan has become heavily dependent on foreign remittances, primarily from the Russian Federation. While the Soviet system provided guaranteed local employment, today approximately half of Tajikistan’s working-age male population must travel abroad in search of low-wage, often seasonal labor in sectors such as construction.

Navigating an environment of increasingly securitized regulation, Tajik migrant workers must often tone down their ethnic markers to mitigate risks of deportation or harassment. In her ethnographic work on Kyrgyz migrant workers in Moscow, Madeleine Reeves (2015) draws attention to the strivings towards “invisibility” that have been cultivated under the conditions of legal precarity and xenophobia. “Like others whom I interviewed in [southern Kyrgyzstan] and Moscow, Bakhtiyar-aka stressed the subtle habits of bodily comportment and dress that he undertook – high-collared coats, Russian highbrow newspapers tucked under the arm, a briefcase for the metro, and sensible shoes – to avoid being identified from a distance as a non-Russian. Others did so as well.” (Reeves 2015: 127)

Thus, the task of reviving, embodying, and performing Tajik national identity falls largely on women – albeit through the channels of a primarily male government. Encouraging – or outright forcing – women to dress in a certain way reflects attempts to foster an unmistakably Tajik, unified public in a precarious environment where many cannot participate or be present, namely migrant workers laboring abroad. The question of national unity is also particularly vexed given Tajikistan’s history with a five-year civil war that ended in 1997.

The government-sanctioned aversion to the “Islamic” (often coded as “foreign”) and the promotion of a “local” are rooted in the insecurities of neoliberal existence in Tajikistan. These anxieties are reflected not only in official discourses but in everyday people’s lives, where transnational kinship structures, major economic difficulties, and the instability of uncertain legal status among Tajik migrant communities in Russia, have contributed to an urge to firmly delineate one’s nationally imagined traditional ideal.

Today, the importance of women in Tajik national dress and the connection between this aesthetic and discourses of unity, stability, and “true” or “correct” national being and family life are visible throughout the country: from popular film and television series, to the Tajik pop queens crooning away in the latest music videos, to anti-domestic abuse billboards around Dushanbe. Legislation concerning women’s attire that began in 2015 coincided with the government of Tajikistan’s self-proclaimed “year of the family.”

Female bodies become a locus of national symbolic value within this context. As one young Tajik woman interviewed for Radio Free Europe commented, “It’s actually harmful for a country not to have its own national dress, because [national dress] helps identify a nation to the world.”

Understanding Tajikistan’s dress code legislation as an attempt to quell “radical” Islam obscures many parts of a much bigger picture. These laws and the public discourse that they both influence and draw from are more than measures to ensure secularity and curb political opposition.

In Tajikistan, independent nation statehood and national revival have taken place amidst the realities of one of the most outbound-labor dependant economies in the world, where overall living standards have deteriorated drastically since the dissolution of the USSR. For Tajikistan, the adoption of “democracy” has brought little in the way of economic prosperity and freedom from an oppressive state. Rather, the state has retreated from the provision of welfare and employment. Precarious, often seasonal labor opportunities and deportability in Russia have rendered most opportunities revocable at best, adding to a collective affect of instability that has proliferated since the Soviet collapse in 1991.

Under the set of circumstances where much of the former proletariat labors away, dislocated from previous ways of life, the bodies of women who remain in Tajikistan serve as one of the primary sites of grounding, anchoring emblems of nationally imagined tradition.

The projection of a distinct, “traditional” way of being is of increasing importance under the forces of neoliberalism as a means of mediating the economic system’s propensity to dislocate and disrupt.

“Tajikistan just not a very well-known brand (u nas brend neznamenity),” sighed Jamshed, a 22-year-old native of Dushanbe. “Especially with so many of us outside of our homeland (vatani mo), it’s therefore really important to promote our image, our brand, our traditions…”

2 comments

Fascinating! Can anyone comment about the role of regionalism in defining standards and preferences of national dress for women? I saw atlas or pink with rhinestones far more often than the embroidered dresses of the south, and Pamiri dress seemed to be popular but also signify a national character of its own. There’s obviously politics involved here, but that’s exactly why I’m wondering. Class, too, actually. It seems rich women didn’t bear the burden of defining national identity in quite the same way as others, but I say that anecdotally. Would love to read any analysis that exists!