The following is a guest post by Gelare Khoshgozaran, an interdisciplinary artist and writer working across film and video installation, performance and writing. She is the co-founding editor of contemptorary.org.

I’d always maintained that the date palm was the weathervane for human affairs. The fortune of the two were inextricably linked. What befell humans was a reflection of the tree’s condition, and war didn’t differentiate between the heads of men and the crowns of the tree: it decapitated them both.

—The Baghdad Eucharist, Sinan Antoon

Life under an embargo can make banal errands, such as mailing a package home, a time consuming feat of bureaucracy if not an impossible task. Last year when I tried to send a small gift to my family in Iran, I was told at the post office it was impossible to send a package to an “embargoed country.” I insisted, and the officer was able to locate a drop-down option on her computer screen, checked a box and finally received my package. The shipment returned at my door in Los Angeles a week later “due to export control regulations” with an obnoxious Return to Sender sign slapped onto a letter addressed to me. I followed the instructions in the letter, browsing the website of the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) for hours. After multiple email correspondences and reading through pages of instructional PDFs I was able to cite one line from an email correspondence as proof that my activity was covered by OFAC’s regulatory authorization: the shipment contained ‘a gift between individuals’ with a value of under $100. I printed the documents, included them in the package and resent it to Iran. A few weeks later it finally met its destination; the state of the facial creams it contained though, questionable.

The movement of objects and the mobility of people over man made borders are entangled in a web of control which makes the relationship between the two more complicated than they may seem at first glance. The same colonial logic that enforces international laws and sanctions to restrict the mobility of people and objects from oil rich countries in the Global South precipitates the extraction of resources from underground. The same land that gives Black Gold also grows native plants, which have provided food for its inhabitants. As water resources grow scarce, and living conditions become harder due to environmental degradation, state oppression, violence or a crumbling economy that more than anything affects the most vulnerable in a targeted country, the need for migration is met with violent oppression, criminalization, and closed borders. Oil can cross borders; refugees cannot.

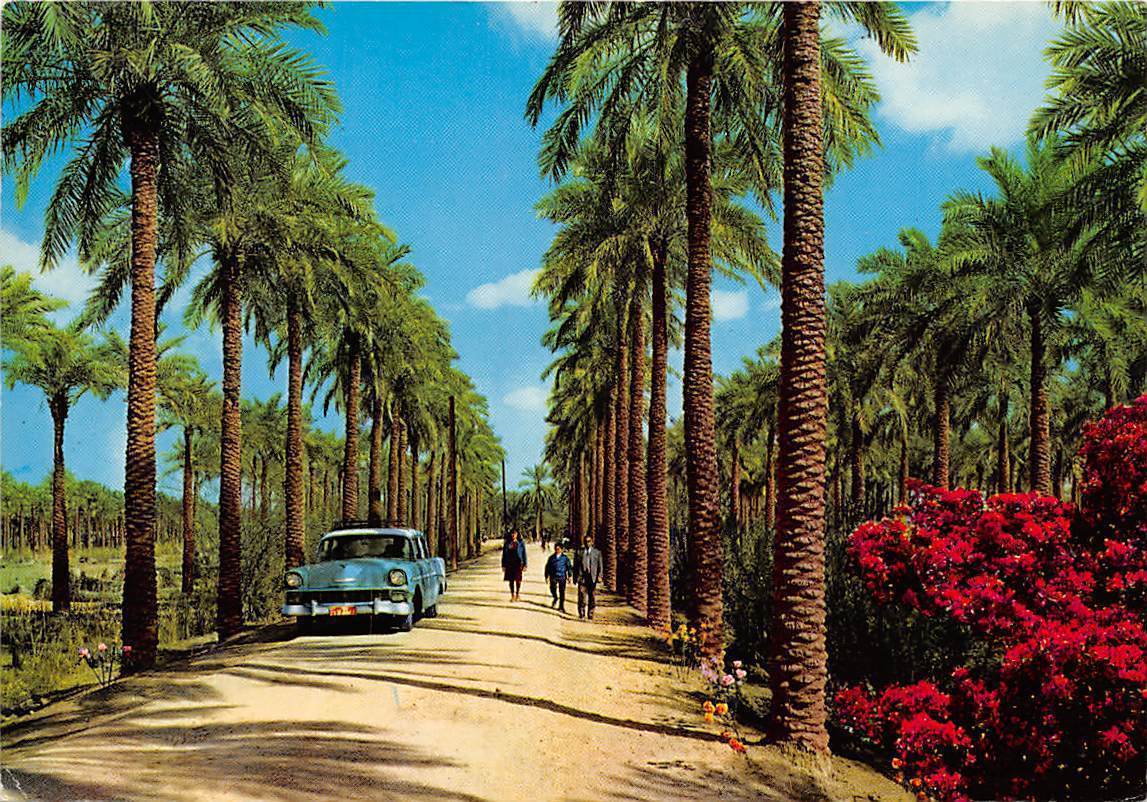

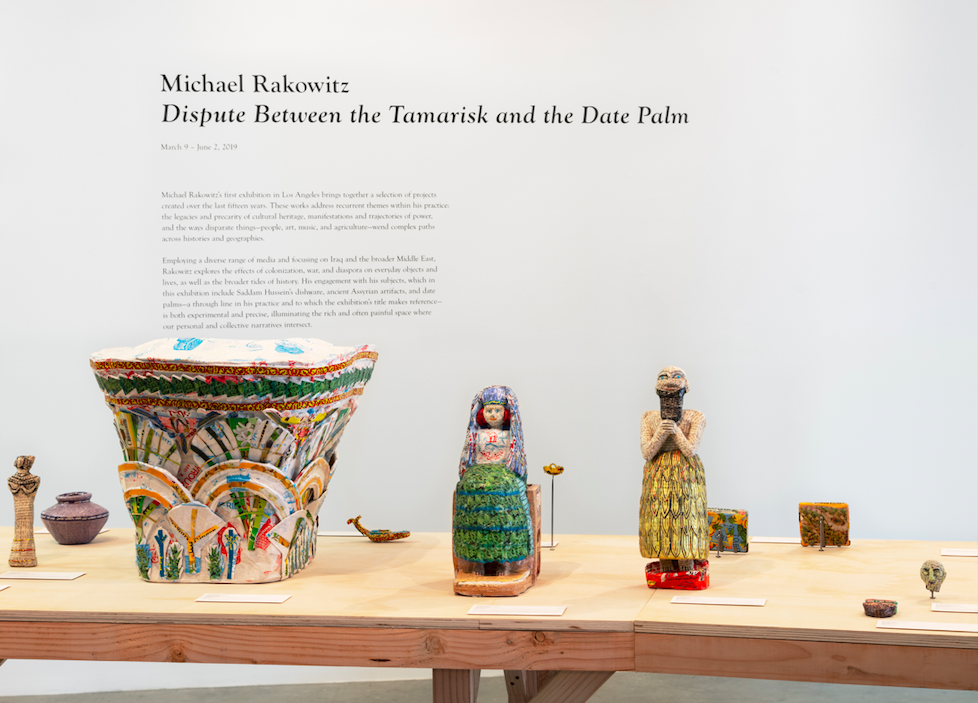

For Chicago based artist, Michael Rakowitz the intricate web of power, control and hypocrisy in this equilibrium cannot but inform his decisions as an artist who creates, participates and refuses to. I visited Iraqi-American Rakowitz’s first exhibition in Los Angeles, Dispute Between the Tamarisk and the Date Palm at CalArts’ downtown space, REDCAT, after a long drive from the west side. With the memory of the Beverly Hills and West LA palm trees still fresh from my slow drive in traffic, I began to wander among the nascent palm trees in the exhibition. On the southern wall of the gallery the artist reproduced the timeline of the date palm from his project Return (2004-ongoing). “A house with a date palm will never starve,” it reads. In other words: to actively starve a house, destroy the palm trees, just as the US war on Iraq devastated the palm industry.

I visited the exhibition on May 8, the day the US unilaterally withdrew from the Iran nuclear agreement (JCPOA), and the Department of Treasury announced an executive order implementing new sanctions on Iran’s iron, steel, aluminum, and copper sectors. AJ+ recently posted a short video of interviews with Iranians during Ramadan where a woman shares her distress about how, due to the economic sanctions, some Iranians can no longer afford to even buy dates and milk, two staples of Iftar for millions of Muslims in the region. While Iran’s date industry continues to play a major role in the international market, the crippling of its economy due to US sanctions undermines Iranians’ ability to purchase dates, among other food. The US can crave a land’s resources while wanting to starve its people—as they did in Iraq and now in Iran.

The landscapes in the exhibit are a world away from California, but they are hardly foreign. Not only are the desert climates of Los Angeles, Baghdad and Bandar Abbas quite similar, their histories are intertwined. Date palms were first introduced from the Middle East to California in the 1890s. Today, four primary kinds of dates are produced as part of a large agricultural industry in the Coachella Valley: the Deglet-Noor, the Medjool, the Barhi and the Zahidi. The idea for Return (2004-ongoing) started at Sahadi’s in NYC which is when Rakowitz came upon a date syrup he was told was from Iraq despite a “Made in Lebanon” label. The date syrup, produced in Baghdad, traveled to Syria and crossed the border to Lebanon where it was labeled and shipped to the rest of the world, including the US. This was a way of circumventing international sanctions on Iraq, beginning in the 1990s, which restricted the export of Iraqi dates. This circumventive method of export, still in practice in 2004, inspired the artist to reopen his grandfather’s import export business, Davisons & Co, which he had opened after settling in Long Island in 1946 as an exiled Iraqi Jew.

Return began with the artist making a deal with an Iraqi business partner, Al Farez, to import dates that were produced in Iraq under the UN sanctions and during the ongoing US invasion to sell them at his newly opened storefront in New York. The dates ended up traveling the same route from Baghdad to Damascus and Jordan that fleeing refugees took out of Iraq. Once the export failed with one ton of dates—originally from Hilla—rotting in Syria, Al Farez offered to send the artist ten boxes of Iraqi dates via DHL. As the store remained open during the wait periods of Return, it transformed into a space where members of different generations of New York’s Iraqi diaspora would gather to share their family histories of migration in anticipation of dates from their homeland they had not tasted in decades. After a painstakingly long journey of scrutiny, the dates finally arrived at the storefront in New York—which until then only sold California dates grown from Iraqi seeds—and were sold to those who anticipated them.

A more recent project in the exhibition, The invisible enemy should not exist (Room Z, Northwest Palace of Nimrud, 2018) recreates seven reliefs and leaves empty spaces for six missing reliefs from the site where the Islamic State group (IS) destroyed pre-Islamic reliefs in Nimrud. When viewed from afar, these replicas are no less majestic than the awe-inspiring originals encountered in Western museums, such as the Louvre or the Metropolitan. Considered world cultural heritage, the original reliefs were deemed worthy of the highest protection, and the infamous video of IS destroying them was violent, disturbing and traumatizing to millions of people around the world. Upon closer inspection, what becomes apparent in the reliefs is Arabic text- they are made from Middle Eastern newspapers, package wrapping and other debris used to create hollow figures, colorful and larger than life, representing Ancient Mesopotamia. The use of newspapers with their classified sections, articles and headlines points to the quotidian intimacy of how these abstracted media headlines from afar touch the food as well as other items consumed by the people whom the content of the news is affecting in material ways: the millions of Iraqis and Syrians impacted by the war and violence.

The presence of shipping, packaging and everyday objects continue in Rakowitz’s other two projects. In The invisible enemy should not exist (2007-ongoing) and May the obdurate foe not be in good health (2013-ongoing) the artist’s studio remakes antiquities looted from museums in Palmyra with cardboard, wrappers and newspaper. Both the title of the works, including the word “ongoing” and the use of disposable, everyday debris to create replicas of ancient artifacts—reliefs, figurines, bowls and containers—make it impossible to think of the antiquities as separate from the everyday life and culture in the Middle East. The IS lootings, which occurred in part thanks to the destabilization brought to the region by the US and allies since the 2003 US invasion of Iraq, are presented as the continuation of the British colonial excavations of the 19th century in this context, and remind us of centuries of archeological excavations by the French, British and other colonial powers in the Middle East that removed thousands of objects from the region to be displayed in Western museums.

Such excavations continue, as two years ago packages marked as “tile samples” from Turkey went through Israel to the UAE and made their way to Hobby Lobby retailers in the US. The innocent packages turned out to be “ancient clay cuneiform tablets that had been smuggled into the United States from Iraq,” The New York Times reports. Following a lawsuit and legal settlement with the Department of Justice, Hobby Lobby forfeited 5,500 ancient Iraqi artifacts with “questionable provenance” bought for $1.6 million. The packaging and labeling, which in the case of Hobby Lobby falsely identified smuggled artifacts as “tiles,” is subject to a different level of scrutiny when a small shipment of food is sent to or from Iran or Iraq by ordinary citizens. In the packages I receive from Iran, for artistic or personal purposes, wrapping not only does not function as concealment but rather enacts an absurd performance of provocation and further scrutiny.

Rakowitz’s use of everyday objects and food items does away with the dominant rhetoric of “preserving cultural heritage,” which in large part relies on dichotomies of “ancient” vs “contemporary,” or “object” vs “human.” His ongoing projects depict the destruction of culture as reflected in the everyday lives of those without whom culture would not exist in a vacuum—the type of historicization the colonial logic of museums is invested in preserving. The apparently museological display in The invisible enemy should not exist and May the obdurate foe not be in good health are accompanied by text that confuses who narrates the histories of these objects, blending the voices of the colonizer, the expert and ordinary people. Quotes from archeologists, politicians, everyday people and journalists accompany the objects in lieu of institutional didactics, making the positions of the “caretaker,” “custodian” and “expert” confused with “looter” and “destroyer.”

While the real names of people are used, their titles are not presented; the voices include Donny George Youkhanna (Iraqi-Assyrian archaeologist, anthropologist who died in 2011), Sara Noureddin (antiquities expert), Maamoun Abdulkarim (Syria’s director-general of antiquities and museums), Fiorella Ippolitoni (researcher of the pre- and protohistoric Art of the Near East), Zeinab Bahrani (Professor of Ancient Near Eastern Art and Archaeology), and Donald Rumsfeld who makes an appearance with the following statement from his April 11, 2003 briefing as Secretary of Defense during the George W. Bush Administration: “Let me say one other thing. The images you are seeing on television, you are seeing over and over and over. It is the same picture of some person walking out of some building with a vase and you see it 20 times. And you think, my goodness, were there that many vases? (Laughter) Is it possible that there where that many vases in the whole country?”

In this and other ways, Rakowitz’s project questions the provenance and colonial modes of both custody and ownership, standardized in western institutions, which inflect a similar violence as any looter or destroyer. In this way, the destruction of cultural heritage by IS, as highlighted by Western media, is not a singular, recent incident rooted in extremist ideology but as the continuation of violent destructions caused by years of UN sanctions, followed by the US military’s invasion, starting from the Gulf War to this day.

The intricate web of such relationships as depicted in Michael Rakowitz’s multiple projects and mediums over the years are reflected in the constellation of questions, objects, appearances and disappearances and in the exhibition’s title. The dispute is between two ancient plants that are infamous for surviving harsh conditions: Tamarisk, for its deep roots keeping the plant alive in the harshest weather conditions, and the date palm which saves a house from starvation. Food, language and culture are not divisible sectors in the way they have been commodified under colonial regimes of occupation, preservation and control. In the exhibition title, what language are the two plants disputing in? As the date palms disappear in their native region amid the wider environmental catastrophe and social breakdown Iraq has suffered since the 2003 US invasion, new palms grow somewhere else without the people for whom they symbolize livelihood, prosperity and wealth and who may offer an interpretation of the language the plants are communicating in.

As I stood there in the gallery looking at the leaves of the young date palms, I was reminded of the scene in Palestinian filmmaker Elia Suleiman’s Divine Intervention where a tourist asks an Israeli police officer for directions in Jerusalem. Clueless about the city he lives in as an Israeli settler with no history in the land of Palestine, the officer opens the back of his van, drags out a blindfolded Palestinian prisoner and has him help the woman with directions. The Palestinian prisoner turns around, points in directions and offers three different routes for the woman to reach her destination all while blindfolded. The second time the woman shows up asking for direction, the Israeli officer checks the back of his van. Finding it empty, he runs back into the van, puts on his siren and drives off.

Michael Rakowitz: Dispute Between the Tamarisk and the Date Palm, curated by Diana Nawi, independent curator, with Carmen Amengual, curatorial assistant, is on view at REDCAT through September 1, 2019.