The following is a guest post by Nidhi Mahajan, an Assistant Professor of Anthropology at the University of California, Santa Cruz. Her work focuses on the political economy of the dhow trade in the Indian Ocean. This research was assisted by a Social Science Research Council Transregional Research Junior Scholar Fellowship with funds provided by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. All article photos were taken by the author.

This article has been commissioned for the inaugural Sharjah Architecture Triennial, titled Rights of Future Generations. It is published as part of Conditions, an editorial collaboration between the Sharjah Architecture Triennial and Africa Is a Country, Ajam Media Collective, ArtReview, e-flux architecture, Jadaliyya, and Mada Masr. Conditions is a series of essays that are published first online and later as a book, available from November 2019.

Irfan, the captain, knew he had done all he could in the face of the cyclone that was approaching. He had moored the wooden vessel, or dhow, at the jetty in Salalah, Oman, for the past week, closely following weather reports that indicated a storm was approaching. Only two days before, on May 23, 2018, they had heard of the destruction that Cyclone Mekunu had caused in Socotra, off the coast of Yemen; more than 120 fishing boats and five Indian dhows had capsized. The cyclone was now heading their way, gathering strength. The cargo remained loaded for safekeeping and to prevent the vessel from capsizing. The dhow was securely moored, all crew members on board. As the storm approached, the sky churned and winds roared as high as 185 kilometers per hour.

Safely aboard the vessel, Irfan took out a small green flag and tied it to a bannister near the cabin, chanting along with the entire crew, “Ya Ghous.” They were calling for the protection of a Sufi saint, Abdul Qadir Gilani, the founder of a Sufi order called Qadiriyya tariqa. The flag also called upon another Sufi, Shah Murad Bukhari, now buried in Mundra, West India, not far from the towns of Mandvi and Jam Salaya that the sailors called home. The green fabric of the flag was cut from a sheet that had once covered the tomb of Shah Murad Bukhari, patron saint of seafarers from West India. The flag carried his blessings.

While the sailors awaited the storm, their kin and loved ones back home rushed to Sufi shrines, praying for their safety. The effects of Cyclone Mekunu, the most intense tropical cyclone ever to hit the Arabian Peninsula, rippled out from Yemen and Oman to India. When the storm abated, Irfan and his crew found themselves safe, even as seven other Indian dhows had sunk in the waters just outside Salalah’s port.

Once the sea was calm again, Irfan and his crew continued their voyage, transporting second-hand cars from Sharjah in the United Arab Emirates to Nishtoon in Yemen. After completing the voyage, Irfan returned to Jam Salaya, making it a point to visit the shrine of Shah Murad Bukhari in order to thank him for keeping him and his crew safe during their voyage.

***

Dhows have long traversed the Indian Ocean. Their characteristic lateen sails harnessed the monsoon winds to transport goods, people, and ideas across the Indian Ocean before Europeans appeared on its shores. Today, dhows from the Kachchh region in western India continue their trade, operating in the gaps between global shipping lines. These vessels, known as Kachchhi vahans, no longer rely on wind, but come equipped with diesel engines. The mechanized wooden ships now go where container ships cannot or will not venture, transporting foodstuffs, diesel, charcoal, dried fish, livestock, and even cars across Indian Ocean ports. Functioning as an economy of arbitrage, dhows quickly adapt to market trends and shifting government policies.

They have found a niche in servicing minor ports in times of conflict, docking in places where container ships cannot reach. With the collapse of the central government in Somalia in 1991, for example, dhows serviced minor Somali ports like Kismaayo. Now that container shipping has resumed in most of Somalia, dhows call at the ports of war-torn Yemen, including Shihr and Nishtoon. Sailing on routes that container ships cannot take, vahans today not only move goods across the Indian Ocean; they represent an alternate understanding of time, space, risk, and protection. In the world of global shipping, the dhow offers a vantage point from which to view religion, society, and economy, as well as living and nonliving beings, as deeply entangled with one another. While seemingly archaic, they are crucial to the workings of global shipping and, hence, of capitalism today.

A vahan is a heterotopic space; it is an object continually in motion, connecting different places and ports, while being a world unto itself. For the sailors who live aboard these vessels for more than nine months of the year, it is a place of work, with the day divided into monotonous six-hour shifts. Yet it is also a domestic space; the sailors rarely leave the vahan, even when docked at ports. The dhow is a heterochrony that holds together the past, the present, and the future. Today’s sailors gesture to both their ancestors and the Sufi saints that previously moved across the region, while planning new journeys.

For Kachchhi dhow sailors, time and space are felt, lived, calculated, moved through, and monetized using one unit: the voyage; or, as it is known in Kachchhi, the ghos. A ghos indicates a movement from one point to another, linking discrete sites. As dhows voyage from India to the Middle East and East Africa, they connect port cities, such as Mundra in India, Dubai and Sharjah in the UAE, Kismaayo and Berbera in Somalia, and Mombasa in Kenya. They bring these sites into relation with each other, creating a transregionalism that belies national boundaries drawn on land.

Yet, the dhow trade depends on the unbalances created by these national borders. Dhows, after all, function as an economy of arbitrage, bringing goods found in abundance in one region to another that lacks them. The price difference between goods in these distant markets is what creates value for the trade. The ghos is thus the point at which difference is arbitraged; it is the moment and movement through which profit is made (since every trip is a transaction).

***

For sailors, life is lived on the line drawn on nautical charts and maps representing the ghos. As historian Johan Mathew has shown, in maps created by Kachchhi dhow sailors, land and sea were not represented in a grid form; instead, the map took a view from the deck. The coastline was drawn in detail to allow sailors to navigate unpredictable rocky cliffs, sudden shallow sandbanks, and dangerous whirlpools.

Unlike European maps, distances were not accurately measured and depicted, but still the ghos was represented as a line that cut across the aqueous topography. GPS is now the preferred tool of navigation for even the most skilled navigator (maalim) in the contemporary trade. Place-names have become dots on a screen, and a moving line guides the voyage.

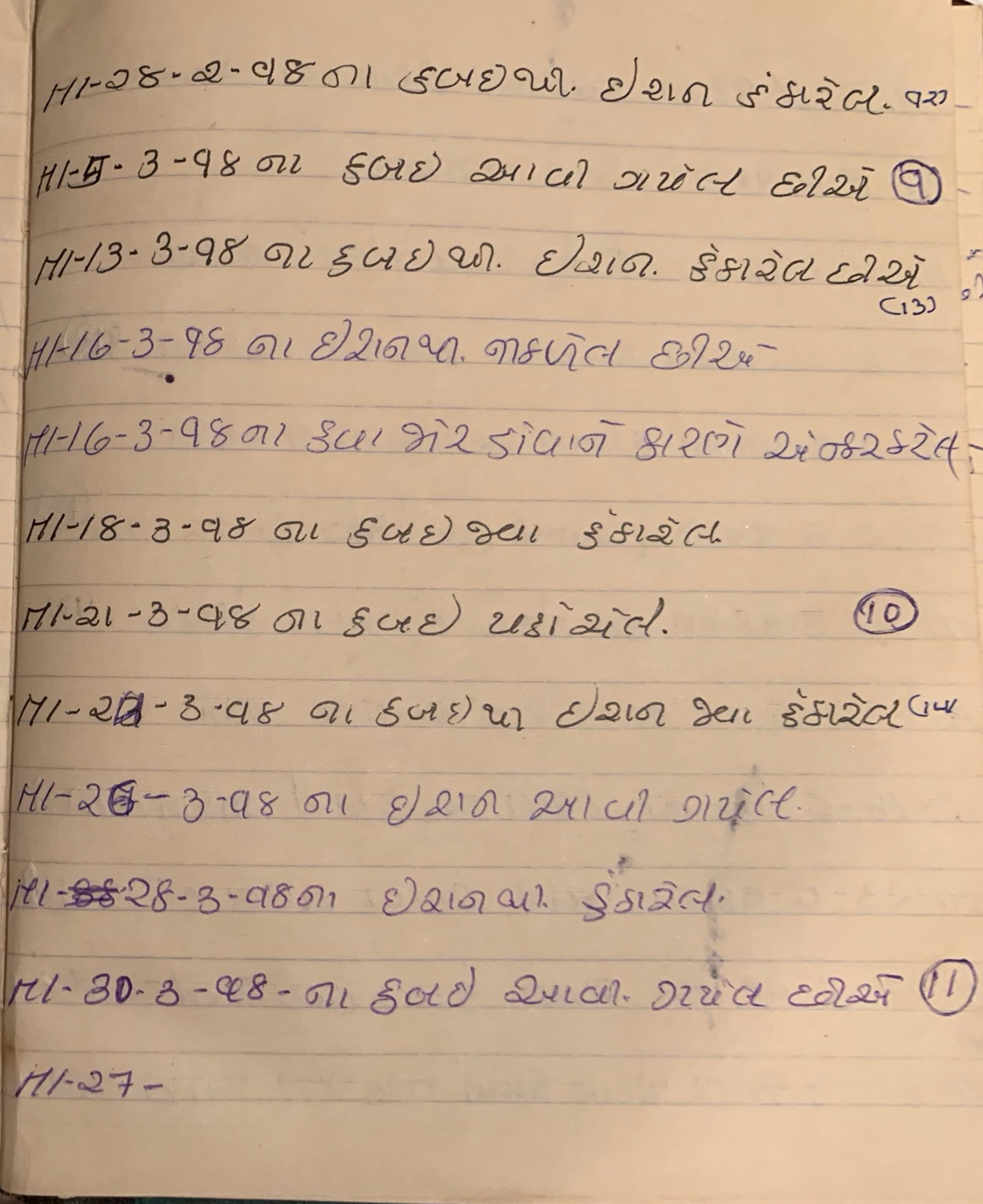

The sailors’ own logbooks appear as a list of voyages. Abdul, a dhow captain from Mandvi, recently shared an old logbook with me. The log, written in Gujarati, reads as a list of places where Abdul arrived and from which he departed. For example, one of the entries states that on March 26, 1998, he arrived in Iran. Yet, much of the logbook is written in code. As we went through the entries on the page, Abdul smiled at me, and said, “Even though I’ve recorded every ghos, the place-names are not accurate. When I write ‘Iran,’ I may actually have been in Iraq.”

Abdul had earned a fortune for his boss, the owner of the dhow, during the Gulf Wars, by smuggling goods across ports that had international sanctions against trade. “For a sailor like me, what matters in these coded records is not the place-name—no one needs to know that—but keeping count of the number of ghos I took in a season,” Abdul told me. Words in the form of place-names can be used by smugglers to purposefully mask what lays between them. Place-names are written as a mnemonic device, in order to spark the memory of particular journeys.

***

A sailing season is a series of ghos. A sailor hopes to make the maximum possible number of ghos through the season, since his livelihood depends on it. Both the boat owner’s revenue and the sailor’s wages are calculated based on the number of ghos undertaken in a season. In every season at sail, a sailor hopes for at least seven different ghos.

The ghos was, after all, once fully dependent on the seasons, including the periods of the mausam (in Gujarati), or monsoon. Lateen-sail dhows once moved with the winds, going southwest during the rainy season, from June to September, and northeast from October onward. For Kachchhi seafarers, the year was divided into aakhar, when the southwest monsoon began, and mausam, when the winds changed. Aakhar was a rainy period during which most seafarers would return home, while mausam referred to the nine months that sailors were at sea. These days, dhows run on diesel engines, but sailors continue to live seasonally.

Every ghos is still set against the unpredictability of the weather and the sea: waves, winds, and currents are ever shifting, especially as the Indian Ocean contends with climate change. Winds are now less predictable, and tropical storms and cyclones ravage the region. It is this risk that makes the ghos, itself, the unit of value and profit.

However, the ghos is not only an economic unit. It is deeply entangled with ideas of time and religious beliefs, as both the living and nonliving intercede at different moments. A successful ghos depends not only on a skillful captain, an able navigator, functioning equipment, a competent crew, good weather, and profitable cargo, but also on the blessings of saints of the sea. In a region wracked by unpredictable weather, the intercession of saints acts as a form of insurance, a method of safeguarding against the dangers of the sea. Here, human agency is limited: in a storm or squall, there is only so much one can do. Yet, where the labor of those who live fails, Sufi saints capable of miracles (karamat) are seen as able to intercede for the safety of those on board.

The sea is thus alive with spirits. For Kachchhi sailors, a zinda pir (“living saint”) called Darya Pir (“The Saint of the Sea” ) reigns supreme. At the beginning of every sailing season, Darya Pir is venerated on land. Sailors carry his flag through their towns, placing it aboard their vessels as they prepare for the next season at sea. It is the green flag of Darya Pir and his constellation of other saints of the sea that guides a ghos, comforting not only those at sea, but also their loved ones at home. Shrines of Sufi saints in India become local nodes, spaces in which these saints can be called upon to protect vessels at sea. A green flag atop a dhow marks the saints’ blessings. Yet sailors must also visit shrines before a ghos –and their loved ones often go during a ghos— to keep the vessel in the saints’ sphere of influence.

Shah Murad Bukhari, the saint that Irfan invoked, is also known as “the Second Saint of the Sea.” He arrived in Mundra from Bukhara around 1660, making part of the trip on a vahan, as sailors still remember. After the saint’s passing, women, men, and children traveled to this shrine, worried about the safety of those at sea. They would enter a feature in it known as the “Window to the Sea,” a tiny room where Shah Bukhari, the now-dead Saint of the Sea, would suggest to their hearts whether or not their loved ones were safe.

Today, the window is boarded up, the saint silent, and WhatsApp carries messages across the sea. These days, models of vahans are left at the shrine, as offerings to the saint to protect the voyages to Somalia, Yemen, Oman, and the UAE. As the vahans sail, they carry the blessings with them. On every ghos, these silent saints enable mobility. If the sea is history, as Derek Walcott wrote, then this is a history of the ghos, where the past is always present, and invisible specters guide vessels across turbulent waters.

1 comment

A wonderful article of Dhow travels in the Indian Ocean. My grandfather travelled from Gujarat to Kenya in the 1920s. I am interested in learning more of the early 20th Century dhow travel. Do you have any references I can follow up on?

Thank You