The following is a guest post by Ashkaan Kashani, an Iranian-American musician and a graduate student in the Department of Near Eastern Languages and Cultures at the University of California, Los Angeles. His research interests include Persian literature, Islamic philosophy, and psychoanalysis.

Mohammad Reza Shajarian, one of the greatest virtuosos in the history of Persian classical music, passed away in October 2020, at the age of eighty. The absence of his sublime voice will be felt for many years to come. Tens of thousands of Iranians attended his burial ceremony in the ancient city of Tus to pay their respects, while Iranians around the world entered a state of mourning. Following his death, Shajarian was interred alongside the mausoleum of Iran’s national poet Ferdowsi. This was a consequence of more than just their joint Khorasani heritage; it was justified by the fact that Shajarian was a monumental figure in Persian music and a beloved Iranian cultural icon.

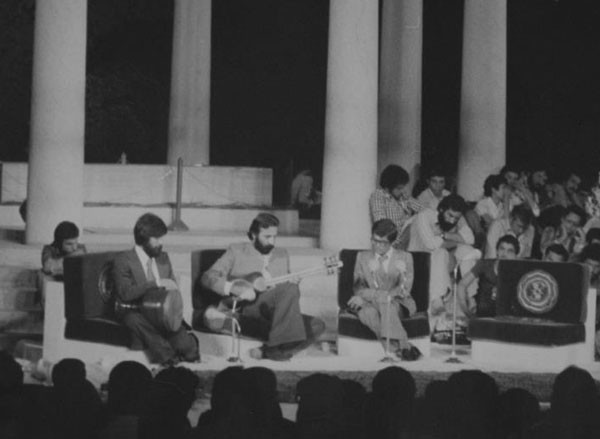

Three years before the 1979 Iranian Revolution at the Shiraz Arts Festival, Shajarian performed with two other icons of Iranian music, tār and setār virtuoso Mohammad Reza Lotfi and tonbak master Nasser Farhangfar. In death, Shajarian joins both Lotfi and Farhangfar, marking the disappearance of a generation of musicians who matured, in musicianship and demeanor, amidst the Revolution and Iran-Iraq war.

For some, this generation’s passing marks a “turning point in the history of classical Persian music and its spectacular rise and fall as a performing public art.” One need only glance briefly at the myriad documentaries, books, and articles which detail the vibrancy, or better yet militancy, of Iran’s traditional music during the revolutionary period to comprehend the sheer historical event of Persian classical music at this particular juncture in space and time. The locomotive of political revolution simultaneously cultivated and was cultivated by a dynamic revolutionary situation in Iran’s traditional music scene. Musicians recorded and distributed cassettes of revolutionary anthems in the streets to an eager audience.

The revolution fostered a set of musicians and composers, led by Lotfi, Hossein Alizadeh, and Parviz Meshkatian, who met their musical tradition at a critical moment and went on to achieve canonical status in the history of Iran’s traditional music. As Lotfi recounted in a lecture two years before his death, “The revolution was like a spring which opened suddenly and catapulted everyone into the air. A lot of people developed in this environment. They read, they experienced things, they read poems, they read history. Everyone was in a frenzied state of learning.”

In the years that followed, the situation changed. State-sponsored radio was restricted and many Iranian musicians fell on hard times. But no amount of restriction could preclude Persian classical music from remaining a deeply respected, lived aspect of Iranian culture. Today it serves as one of the most popular avenues of artistic expression in Iran.

And what about outside of Iran? Many musicians left after the revolution and during the war, mostly for Europe and North America, joining a diaspora of several million Iranians. But does Persian classical music have any place outside of Iran? How can it, given that it seems to be an essentially regional genre of music — inextricably woven into the cultural fabric of a people? In Iran, it is referred to only as musiqī-i sonnatī (traditional music). The question in musiqī-i sonnatī is latent, “whose traditional music is it?” and the answer is apparent, “it is our collective traditional music.” To whom does musiqī-i sonnatī belong when it becomes, in English, Persian classical music?

After Lotfi’s death, Hamid Dabashi suggested an answer: “Outside Iran, Persian music is staged either as an ornamental museum piece for the Oriental fantasies of foreigners and their ‘ethnomusicologists’ or else for the expat nostalgia of bygone years.”

He confronts us with the following problematic: when a non-Western musical tradition is displaced and performed outside its originary context, it is either being staged for the exoticizing gaze of foreigners or conforming to a temporally ossified version of itself to cater to diaspora nostalgia. In both scenarios, the transplantation of a non-Western musical tradition into Western society suspends the dialectic conflict and growth which defines the vibrancy and subsistence of a musical tradition as art.

The problem, as Dabashi defines it, is how can a displaced musical tradition maintain its artistic value — how can it operate according to its self-defining criteria of worth — when it is relegated to the gaze of Orientalist oddity? If the portrayal above is accurate, then it cannot. It is only in its originary, and therefore proper, cultural context, performed for a critical audience steeped in the centuries of history which shaped the music that recounts the story of their own selfhood, that such a tradition can be dynamically engaged with and flourish.

Historicizing Persian Music

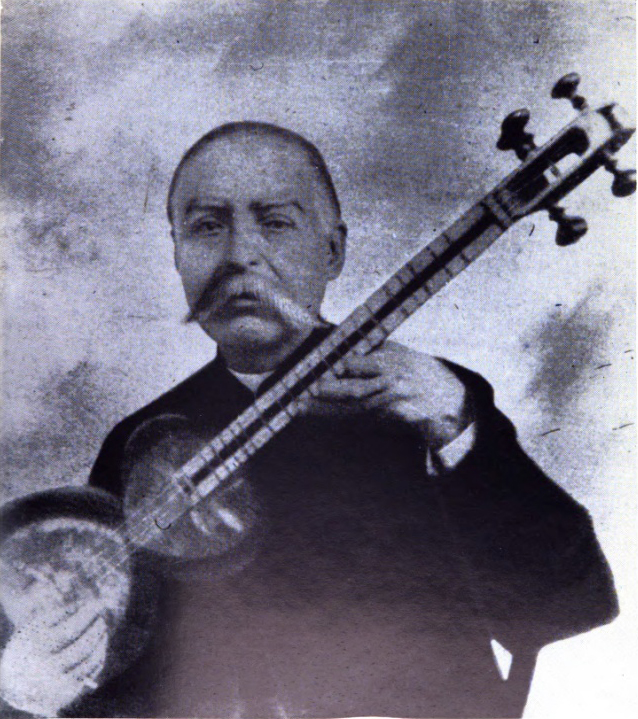

Yet, such a narrative betrays an incomplete understanding of Persian classical music’s history. The term Persian classical music is itself a designation of Orientalist ethnomusicology. In Iran this music is simply called traditional music, referring to music based on a collection of modes and melodies called the radif, specifically the radif of Qajar-era court musician Mirza Abdullah (d. 1917).

His radif is an origin among many others in the history of Iran’s musical culture. Mirza Abdullah did not invent a tradition called Persian classical music. Rather, he formalized and systematized the repertoire of melodies which his father, Ali Akbar Farahani, also a famous musician, had gathered during his tenure in Nasir al-din Shah’s court (d. 1896). The Qajar court was a cosmopolitan meeting ground reflecting the diversity of the peoples in the empire’s extensive domain. Farahani and his sons, Mirza Abdullah and Mirza Hossein-Qoli (d. 1916), canonized and systematized a series of melodies (gūsheh) entering the court from across greater Iran, with temporal origins now largely ambiguous. As Alizadeh pointed out during a seminar at UCLA, “You cannot say that the radif belongs to the Qajar era. In the Qajar era it was edited and collected in a particular way.”

There is no universal, fixed repertory of these melodies. Although Mirza Abdullah’s radif remains the standard, there are different versions. The reason for this variation is that it is never performed verbatim. The collection of melodies comprising the radif are organized into twelve musical modes (dastgāh and āvāz) which serve as a basis for improvisation. Every master (ostād) has their own interpretation.

If we look at the names of the melodies and modes from Mirza Abdullah’s radif, we are met with an array of geographical, tribal, and cultural signifiers from across the Persianate world: Bayāt-e Kord, Bayāt-e Tork, Bayāt-i Esfahān, Bayāt-e ‘Ajam, Rāk-e Hendī, Rāk-e Keshmīr, Dashtī, Gīlakī, Zābol, Bakhtīarī, Afshārī, Hejāz, ‘Arāq, Nowrūz-e ‘Arab, Nowrūz-e Khārā, Shūshtarī, and Māvarā ol-nahr, among many others.

These names show how Iranian or Persian classical music functions within a broader mutli-ethnic Persian identity. Like Persian music from Afghanistan and Tajikistan, Persian music from Iran, which this article focuses on, is constituted by a multitude of cross-regional influences.

Through a historical exploration of Persian classical music, we can see that there is nothing which decisively limits the evolution of this tradition within the borders of any one nation. The history of the radif and the creativity of Iranian musicians living in the West demonstrate how the blanket dismissal of Persian music outside of Iran as derivative or unoriginal is itself a recklessly Orientalist position.

Living Persian Music in the West

Persian classical music’s development in recent decades reveals openings wherein practitioners of non-Western musical traditions can redefine and re-establish the value of their practice. Many popular contemporary Iranian musicians, like Kayhan Kalhor and Hossein Alizadeh, are educated in the West and remain arguably the most esteemed traditional musicians inside Iran, consciously and carefully collaborating with both Western and non-Western, non-Iranian artists.

The re-evolution of Persian classical music across national boundaries calls into question the very notion of a primordial originated-ness for any musical tradition by showing how such origins are being constantly and retrospectively posited to supplement the traditions which they instaurate.

There is no better way to observe the relationship between the living tradition of Persian classical music and Western society than by looking at the career of Pejman Hadadi, one of Iran’s foremost percussionists. His rhythmic and technical innovations in tonbak have been significant for Persian classical music. Hadadi is currently a visiting professor of ethnomusicology at the University of California, Los Angeles. According to Dabashi’s framework, this indicates he is simply another Westoxified collaborator profiting from the academic exotification of tokenized Persian culture. Except Hadadi happens to be an active, well-respected musician and educator in Iran, where he holds workshops and concerts. His tonbak style has become vastly popular among the younger generation and widely appropriated by tonbak players, and he has collaborated closely with Iran’s most celebrated musicians, including Alizadeh with whom he challenged the conventions of duets (do-navāzī) by accompanying him through seemingly ‘non-rhythmic’ (āvāzī) portions of the radif.

Hadadi has been at the forefront of a rhythmic renaissance in Persian classical music. Rhythm in Persian classical music has its roots in the complex metrical system of classical Persian poetry. For this reason, it has been historically cyclical in nature, counted as a series of beats which, unlike the Western system of short measures, can form an asymmetrical and uneven totality, often with a fixed pattern reflecting the syllabic meter of Persian poetry.

But the rhythmic cycles of music historically performed in Iran have been lost in the past few centuries, almost irretrievably so after the importation of the Western notational system of congruous measures with equal numbers of beats. Tonbak players like Hadadi and Pedram Khavarzamini, based in Canada, have led a revival of traditional music’s much older cyclical system.

Hadadi attributes a large part of his innovations, or rather recollections, in tonbak to his interactions with non-Iranian musicians, specifically Indian tabla players and percussionists with whom he became acquainted in Los Angeles. He spent several years studying tabla and rhythm in Indian music, which maintained the system of rhythmic cycles, formatively shaping his approach to the tonbak — an approach which has gone on to renew essential aspects of tonbak playing in Iran and alter Iranian musicians’ view of rhythm.

In this 2010 video, Hadadi (center) performs a percussion solo utilizing a split-hand technique on tonbak adapted from Indian percussion instruments, cycles which do not fit into symmetrical measures, his signature tunable frame drums (pezhvāk), and towards the end, a skin added on top of the tonbak for texture, during a concert in Venice, Italy with the Iranian tār and setār virtuoso Hamid Motebassem (right) and the Azerbaijani kamāncheh master Imamyar Hasanov (left), who reside in the Netherlands and California respectively. The trio released an album in 2012 under the title Persian Azeri Project – From Shiraz to Baku:

This is not an instance of the old Orientalist trope where the colonial subject emigrates in search of a Western education and returns to the homeland bringing knowledge of the master’s marvels. The Western context, here, subverts its own epistemological hegemony. It is in the West that percussionists such as Hadadi and Khavarzamini have been able to challenge the imposition of rhythmic notation from Western music theory and recollect the historically predominant, non-Western system of rhythmic cycles. It is also where they interact with other traditions, like the Indian and the Azeri, which in the past were in close conversation with Iran but today are isolated by borders and geopolitics. The result of these interactions dislocates the concept of tradition from the homeland, as Iranian musicians re-learn aspects of their own musical practice lost in political transmutations but which remained intact in nearby musical cultures.

One of the most famous Iranian music ensembles is the Dastan Ensemble, a group which owes a large part of its success to Hadadi’s innovations. Many of its members, some of the greatest contemporary masters in Persian classical music, live outside of Iran. The group has collaborated with Iran’s most celebrated vocalists, including Shahram Nazeri, Homayoun Shajarian, Parisa, and Sedigh Tarif, but has always prioritized instrumental music in a tradition conventionally dominated by singing.

The idea that so-called non-indigeneous musical traditions cannot be anything but a shadow of themselves, cheap representations, outside of their original contexts at once presupposes a dangerous essentialism and itself engenders the kind of paralyzed socio-cultural impotence which it presupposes. Every tradition, musical or otherwise, refers back to an origin. Yet, as we well know, there must be something constantly originary in that which the origin originates. The origin of Persian classical music that is the radif itself originates in melodies from across the Persianate world whose histories and origins mostly dissipate into time eluding us. Since its apparent inception the radif has existed as a multiplicity and a well-spring for improvisation and composition.

The radif acts not as a terminus but as a nexus from which one simultaneously departs and returns. It is an origin which is supplemental, as Derrida would describe it, but an origin nonetheless. The radif is a collection which demands to be recollected. With each recollection, it occupies a different time and a different place, never quite the same as it was when it was captured for the mythical first time. As a repository of constantly recollected sounds, the radif allows for the perpetual revival and breathing anew of a tradition called Persian classical music.

For the past few decades, Los Angeles has found its way as part of the history of Persian music — an origin. Los Angeles has a larger concentration of Iranians than any other city outside of Iran, hence the moniker Tehrangeles. Among this sizable diaspora are a number of talented expatriate musicians who identify with a variety of genres. Tehrāngelesī culture, as chronicled in Farzaneh Hemmasi’s Tehrangeles Dreaming, famously gave rise to a golden age of Iranian pop music in the 1990s and early 2000s, today an integral part of Iranian national identity and cultural imagination.

All of this is not to erect an imagined space of the West as the elect domain wherein music reaches self-actualization. Instead, what we must acknowledge is that what is called the West is not the cultural abyss that it is made out to be. The Western genre of world music is a profoundly problematic category. The Western academic discipline of ethnomusicology is a limited institutional practice, and certainly not the only way a musical tradition should be encountered.

For many Iranian musicians living abroad, the limitations of these categories have been surpassed from and within themselves. One can be an ethnomusicologist or release albums which the US Recording Academy classifies as “World Music” while not only maintaining the integrity and authenticity of traditional music, but also meaningfully contributing to it in a manner that both departs from its origins and recollects them. Although the works of Shajarian and Alizadeh may be marketed to Western audiences as world music, that does not mean that their music is not encountered in meaningful ways (even by Western audiences) or that it is universally encountered as an exoticized stereotype. And despite being an outwardly Orientalist category, non-Western musicians have appropriated it as a unique space which allows them to gain a deeper understanding of the interconnectedness of their musical traditions.

Even before their passing, Shajarian and his generation were already implicated in the West and vice versa. In the last phase of his career, Shajarian carried out his final set of world tours with the Shahnaz Ensemble, a group founded in 2008 and led by Majid Derakhshani (b. 1957), a former student of Lotfi who has since immigrated to Germany where he has lived and taught for many years.

Shajarian’s collaboration with this ensemble showed his commitment to help the younger generation find their place within the long history of Persian music. It seems that even Shajarian understood that the landscape of Persian music is constantly evolving and that he, rather than belonging to a bygone golden age, continued to occupy an active role in shaping the trajectory of this evolution.

Oct 2011: Shajarian and Derakhshani performing with the Shahnaz Ensemble in London, UK.

Two years before his death, Lotfi was asked during a talk what he thought about innovation (no-āvarī) in traditional music. He responded by saying that when he, Alizadeh, and Meshkatian began playing professionally during the Shah’s reign, the situation was so critical that they sought only to bring Iranian music (Lotfi emphasized that he preferred the term Iranian rather than sonnatī) “out of the closet and back to the people.” After the revolution, he continues, they each added new “forms” to the old ones, pointing out his albums Chavosh Six and Chavosh Eight as examples, forms which “even since the time of the Qajars were not customary (marsūm).

In this video from c. 2008-2009, Lotfi performs the song (tasnīf) Sepideh from his Chavosh Eight album, with lyrics written by the modernist poet Hushang Ebtehaj (H.E. Sayeh), many years after it was first recorded live in 1978 by his Sheyda Ensemble with vocals by Shajarian. The structure of this piece, like many in the series of twelve Chavosh albums composed by Lotfi, Alizadeh, and Meshkatian around the revolutionary period, was unprecedented in Iranian music and large ensembles like the one in the video hitherto unseen:

Today, new forms, or rather old forms, are still being added to Persian music. While they may not have the raw, spectacular energy of political revolution behind them, they are nonetheless revolutionary.

As Alizadeh puts it, “Innovation (no-āvarī) is a synonym of the word artist. All of the world’s artists only attain renown once they’ve created something different, when they haven’t just imitated another person. And it’s always been shown in history that art is so vast that we never need to worry about it being repeated. There will always be some who come along and create things … So when we use the word innovation, we are talking about one of the necessities and essential phenomena of art.”

References and Further Reading

Hemmasi, Farzaneh. Tehrangeles Dreaming: Intimacy and Imagination in Southern California’s Iranian Pop Music. Duke University Press, 2020.

Lucas, Anne E. Music of a Thousand Years: A New History of Persian Musical Traditions. University of California Press, 2019.

Nooshin, Laudan. Iranian Classical Music: The Discourses and Practices of Creativity. Routledge, 2014.

Siamdoust, Nahid. Soundtrack of the Revolution: The Politics of Music in Iran. Stanford University Press, 2017.

Simms, Rob, and Amir Koushkani. The Art of Avaz and Mohammad Reza Shajarian: Foundations and Contexts. Lexington Books, 2012.