The following post was written by Kimia Maleki, a graduate student in the Department of History of Art at Johns Hopkins University. Her work focuses on historiography, archiving, and curatorial practice, particularly as pertains to Iran. Read her previous articles here.

When I came home to my Chicago apartment one afternoon in the summer of 2018, the last thing I expected to see was a package from Iran. The Muslim Ban had come into effect several months before, trapping me in the U.S., unable to see my family, and President Trump had just imposed new sanctions on Iran. As I approached my doorstep, I saw the dark blue logo of Iran Post shining on a yellow package. Even though Iranians have been largely banned from moving freely, packages such as boxes of cookies, pistachios, saffron, books, and medicine still make their way between Iran and the United States. Surprisingly, throughout 40 years of tensions, sanctions, and hostility between these two countries, the postal services of Iran and the United States have always maintained cordial relations. Even when our bodies were perceived as threats, our gifts and packages were allowed to fly–even if they were often delayed by a few weeks or months without any tracking number.

Since 1979, when the relationship between Iran and the U.S. dramatically soured and previous connections were torn apart, one of the few sources of hope for many has been that they send letters and packages between these two geographies. Due to the recent round of sanctions on Iran and the collapse of the Iranian currency, quality has suffered and fees have risen. Regardless, packages still move between Iran and the United States. Iran’s postal service has had a central role in this, symbolized by its logo depicting a bird flying freely. The image brings to mind the logo of the U.S. postal service USPS, an eagle. However, Iran’s postal bird flies from east to west, and the USPS the other way around.

Today, Iran’s postal service has a key role in connecting the country to the world amidst sanctions and political tensions. Its history spans back millennia, but the contemporary post system is tied to the development of Iran’s modern state. In this article, I explore how Iran’s postal history, as well as its changing logo, reveals insights into Iran’s changing place in the world.

Early Roots

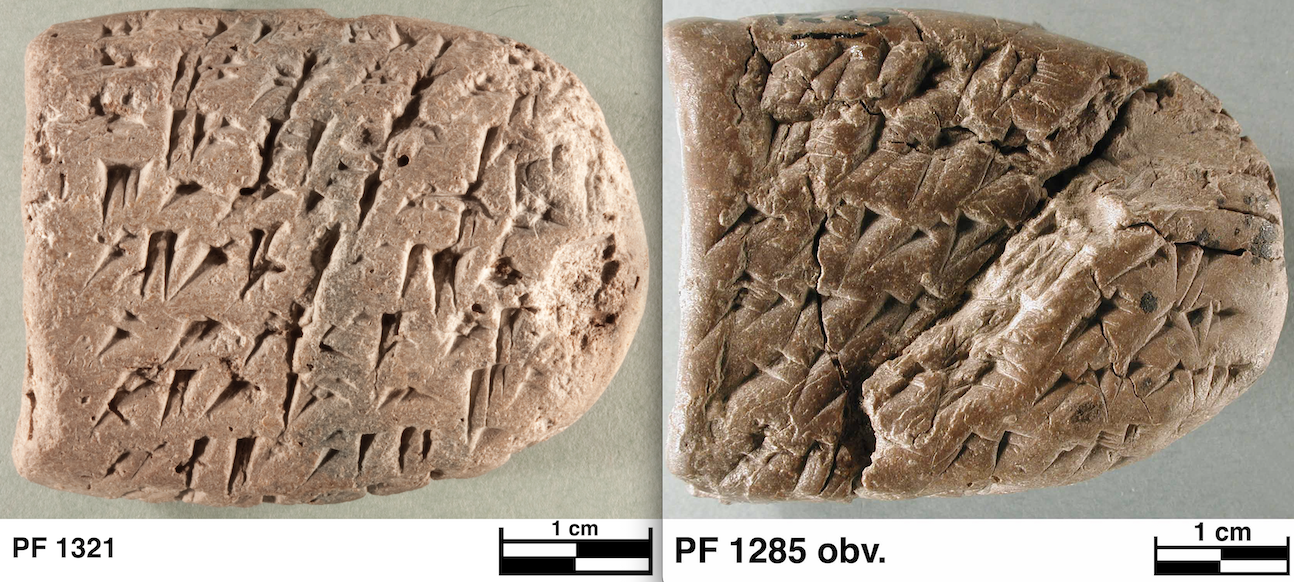

Iran’s postal service dates back more than 2,000 years, to a time when the concept of a postal system developed in several nations including Egypt in the Middle East. It was under the Achaemenid Empire (550–330 BC) that the system thrived along the royal road. Growing up in Iran, we learned about one of the great inventions of the era: chāpār, referring to an ancient postal relay system then known as pirradazish in Old Persian, meaning “express messenger”– where men with horses stationed every few miles to deliver letters. This allowed letters and goods to be sent across the Persian Empire, from Susa to Sardis (2673 kilometers/1660.925 miles) in about 11 days.

This institution is attributed to Darius (550–478 BC) the third Achaemenid king. The Persian empire reached its largest extent under Darius, and so did the postal system. Darius’ image is even featured on the façade of the old main post office in Berlin due to his role in the development of the system and its impact on the modern global postal system.

The US Postal Service (USPS) even adopted one of Darius’ reported statements as an unofficial motto carved into the main post office in New York City: “Neither snow nor rain nor heat nor gloom of night stays these couriers from the swift completion of their appointed rounds.” The USPS is the only American postal service that delivers packages to and from Iran until today, unlike private postal services such as FedEx and UPS.

The Achaemenid postal relay system was adopted by other dynasties in the years that followed, operating across the region. The system known as barīd became part of the Islamic caliphate and was used both to transfer decrees and for intelligence affairs.

Iran’s Modern Postal History

The history of Iran’s modern post system began in the late 16th century when the Safavid Empire (1501–1722) adapted words used in the past to describe their system. Safavids substituted the word chāpār “express runner” and chāpārkhāneh “relay stations” for the system. The royal road of Achaemenid was built in hopes of sending royal messages from the eastern part of the empire to the northwest of Persia which is located in today’s Turkey.

Later, in the Qajar period (1786–1925) under the supervision of Amir Kabir, the chief minister to Nāṣer-al-dīn Shah, the postal service became available for the non-royal public to mail letters by couriers. The postal service at first was a small agency under the Iranian government. It was in 1877 that Iran joined the Universal Postal Union, and by the order of Naser al-Din Shah (1831–1896) it became an organization.

In the 20th century under the Pahlavi Dynasty, the postal service grew into the Ministry of Post and Telegraph. This included the construction of the ministry’s home, a huge building in the bāgh-i melli (National Garden) in central Tehran, currently serving as the Post and Communications Museum. The building was designed in 1934 by Nikolai Markov, a Russian architect who was instrumental in developing the Pahlavi architectural idiom drawing on ancient motifs and modern forms that attempt to connect the glorious ancient past of Iran to the current progressive modern Iran. The logo of the postal system, from its inception in the late 19th century to this time was in accordance with the sun and lion motif mainly used for any governmental service.

After the 1979 revolution, the national postal service logo was changed along with many other logos that had royal and crown elements. This was part of a wider trend toward updating Iran’s symbols in line with its revolutionary future–a process that also created Iran’s contemporary flag. An open call went viral and a young architecture student named Mostafa Kiani from Isfahan (now a faculty member at the University of the Arts in Tehran) mailed his sketches to the competition.

He had sketched the initials of the Post of the Islamic Republic of Iran in Persian as a shape of a bird, he told me in an interview in Tehran. The bird is flying from the east to the west, as he hoped that “the post would become a device to connect these two places,” he explained.

Since Iran used to have connections with the world before the revolution, Kiani likely imagined that his logo would be used to send and receive packages from Iran around the world. My aunt once described to me that in the late 1970s and early 80s, she could order clothes from international magazines, pay in Iranian currency, and receive them at her doorstep in Tehran. My friends and I were amazed to learn that there was a possibility of a commercial transaction between Iran and abroad before the second round of embargos were slapped on Iran in 1984. Due to the total economic embargo the U.S. has placed on Iran since 1979, this is an experience unknown to the current generation of Iranians like myself.

Iran postal service’s logo consists of a dark blue bird flying from right to left. This bird is made by three initials of the Post of the Islamic Republic of Iran, though these are difficult to discern unless you already know they’re there. Iran’s logo is one of the most similar to the U.S. postal service. In many other countries, the postal services are inspired by post horns, which were once used to announce a mail carrier’s arrival. However, Iran and the U.S. have used birds as the logo of their national postal systems, an enduring connection.

Amid the contemporary lack of connections between Iran and the rest of the world, the postal service has remained one of the few between these two nations in recent years. This service does not contain express or priority options, suggesting that the service only functions to send packages that are not inherently vital, likely maintained by the Universal Postal Union.

Even in recent years, when Iranians were banned from entering the U.S., U.S. citizens were advised to not travel to Iran, and the transfer of goods was banned by U.S. sanctions, mail continued arriving. Venmo and PayPal blocked any financial transaction even carrying Iran’s name or the Persian alphabet. But the postal service remained a simple and rudimentary process where families can send nuts, rock candies, and cookies to the U.S., and in response, people mail– with practicing OFAC policies– books, clothes, and medicines difficult to find in Iran due to U.S. sanctions.

The logo of the postal service in Iran and its bright yellow color has been a nostalgic and familiar sign for Iranians for many years. The postal system also operates as a kind of archive of Iranian history through the stamps it releases, which document changing perceptions of Iranian history and politics. Topics such as the fight against discrimination, or in recent years stamps portraying an Iranian-American, Anousheh Ansari, the first female space tourist, and Maryam Mirzakhani, the mathematician have been printed. The Post Museum and Malek Museum in Tehran keep a large number of stamps from the 18th century until the present.

While the traditional post boxes usually have been featured in movies as one of the poetic elements of exchanging love letters (like the movie White Nights by Farzad Mo’tmaen inspired by Fyodor Dostoevsky), the new administration decided to change the logo in 2019.

In line with an attempt to be perceived as a modern and effective organization, the National Post Company announced a new logo to show the rebirth and change in the function of the postal service of Iran advancing toward more global activities.

For a project U.S. Customs Demands to Know (2013–ongoing), Gelare Khoshgozaran mailed packages from Tehran to the United States. She asked her parents to send materials from her childhood including magazines, books, ephemera, etc. They were opened and inspected by U.S. authorities.

“U.S. Customs randomly opens my packages. I wonder what the X-ray machine thinks of my items,” she explained in an interview. While it may seem at first glance that the post is free from Iran-US tensions, in fact, it is constantly being surveilled by authorities. The postal connection between Iran and the U.S. is a lifeline for those who are forced to live between both countries– but it is also subject to the same invasive and discriminatory policies that pervade the rest of our lives.

In 2019, I was able to return to Tehran. As I sat in my apartment in Tehran, the buzzer rang. In Iran, due to the low number of international delivery packages, the postman rings the buzzer and asks for an ID card prior to delivering the package. There have been times that the postman “postchi” asked me for a tip as “shirini” (a sweet) for handing me the package from abroad. Not because he was fulfilling his responsibility but because to him the package from abroad signified a very special event that he thought of as something good and happy.

The “shirini” was a kind of spreading of joy, a compensation for his service in the delivery. I showed him my ID and gave him cash (the sweet he would expect). The USPS eagle sat in my hand in Tehran. For a moment, seeing the bird, I felt that it had traveled all the way from California to be touched by me in Tehran, a world devoid of political tension. Even when all other routes have been severed, the post between Iran and the U.S. represents a vision of connection.

Further Reading