This article was written by Jonathan Brack, an assistant professor of history at Northwestern University. His recently published book is entitled An Afterlife for the Khan: Muslims, Buddhists, and Sacred Kingship in Mongol Iran and Eurasia.

In recent decades, research on the Mongol Empire has changed both academic and popular perceptions of the Mongols. Instead of focusing exclusively on large-scale destruction wrought by military campaigns, scholars have shed light on how the Mongol Empire impacted Chinese, Middle Eastern, European societies and beyond. The Mongol conquerors enabled and promoted the transmission of knowledge, technologies, religions, ideas, and much more across the geographical, cultural, and linguistic boundaries of pre-modern Eurasia.

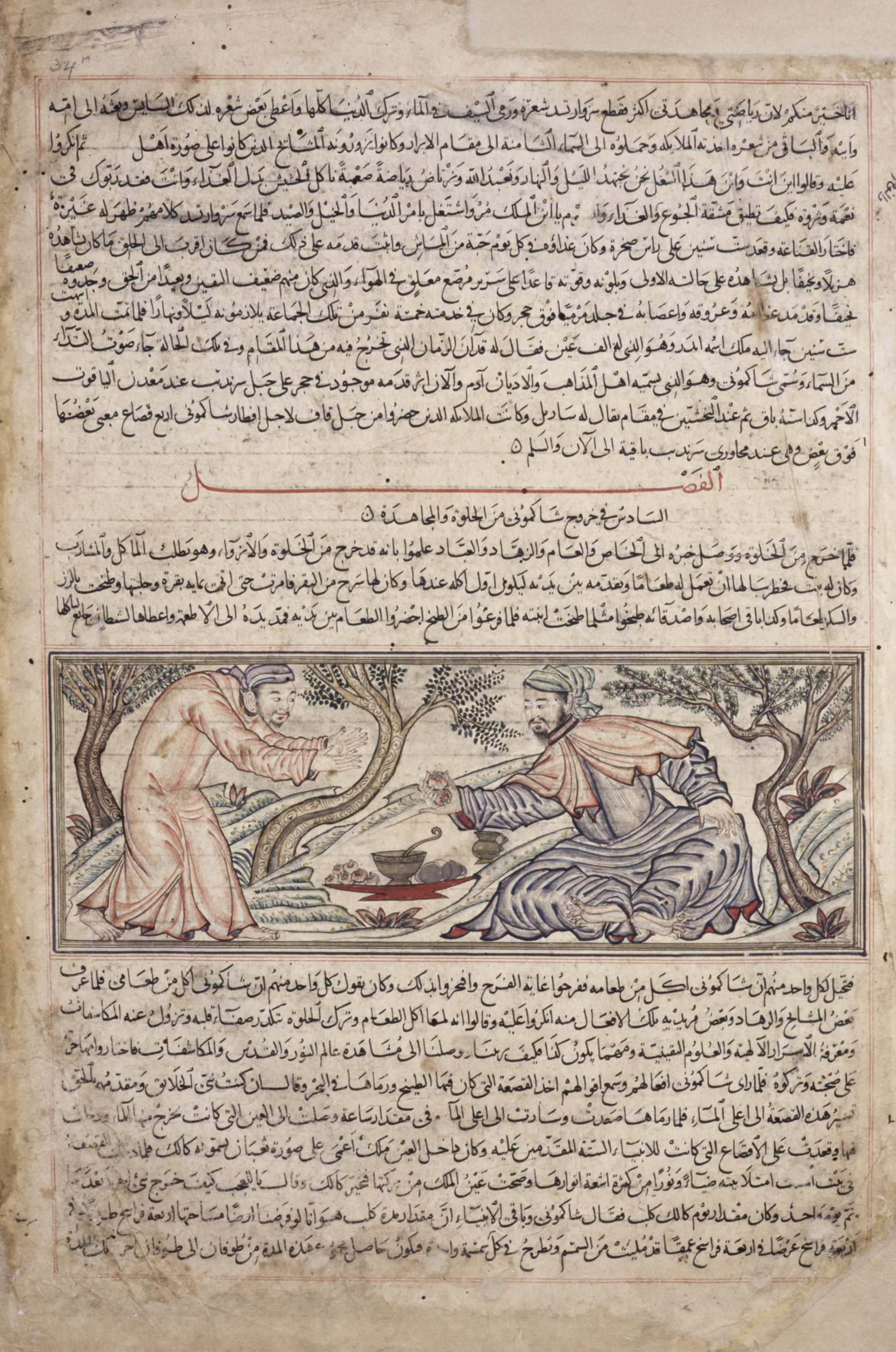

A 2022 controversy shows the importance of studying the inter-religious and cross-cultural encounters at the Mongol Empire and their ongoing relevance in our time. It revolved around an image from Iran shown during a global art history survey class that led to Hamline university canceling the lecturer’s future employment after administration decided the image was Islamophobic. The image in question was a fourteenth-century depiction of the Prophet Muhammad, his face visible, receiving his first revelation from the angel Gabriel. The firing quickly spiraled into a wider controversy, with many academics condemning Hamline’s interpretation of this image as religiously offensive. They argued that considering the image Islamophobic contradicted Islam’s rich tradition of devotional art and pictorial representations of the Prophet.

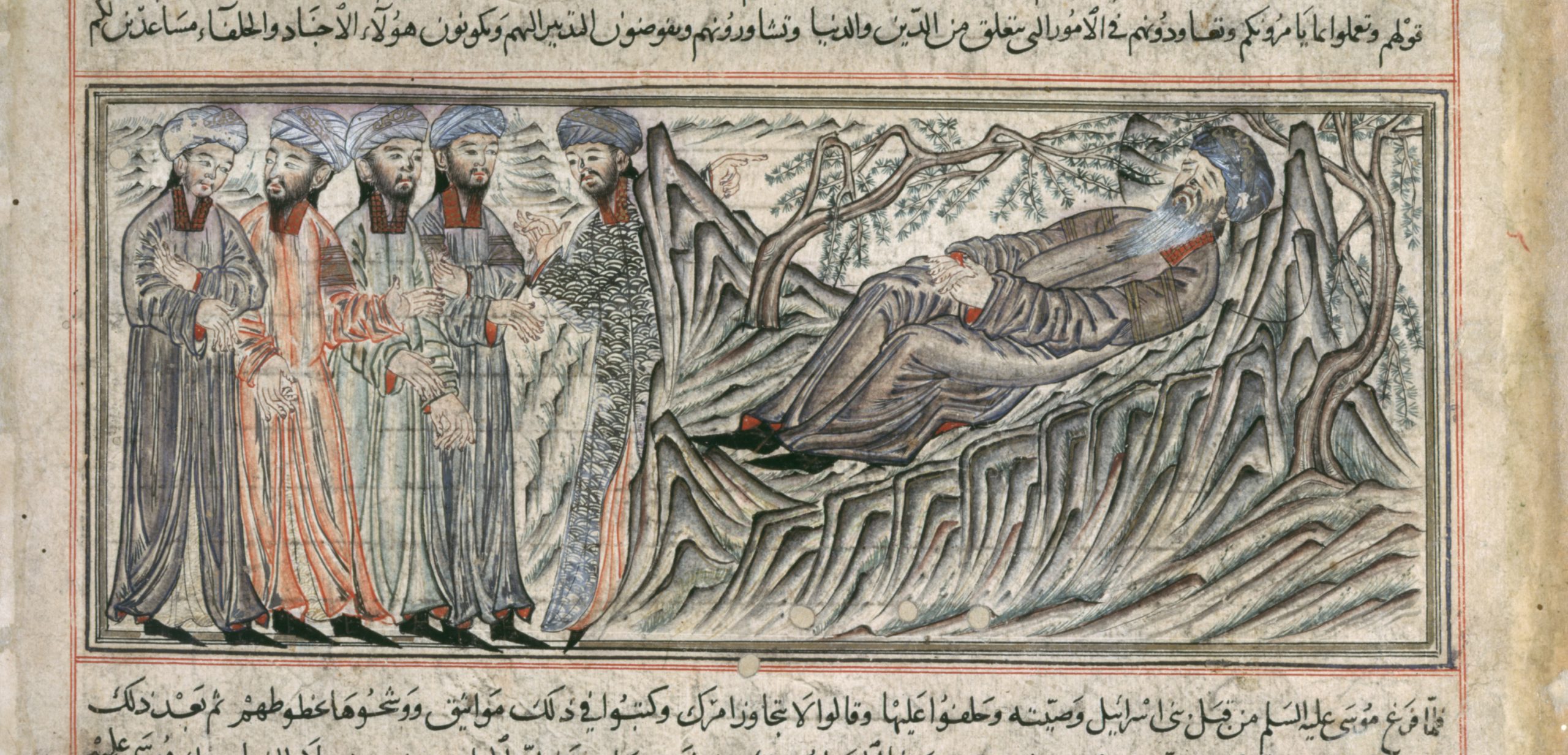

The image originally appeared in a magnificent manuscript of the Compendium of Chronicles (Jāmiʿ al-tawārīkh), a fourteenth-century Islamic world history composed by Rashid al-Din Hamadani in Persian and translated into Arabic. It is one of a dozen or so illustrations describing scenes from Muhammad’s birth, life, and career, especially his heroic deeds – battles and miracles – on the path to securing Islam’s triumph. Other prophets, from Abraham to Moses, and even the Buddha, presented as an Indian prophet, appear as well. But no other individual receives the same pictorial attention as Muhammad. This manuscript was the most ambitious attempt to illustrate Islamic sacred history to date. It was produced in Iran under the patronage of Mongol kings who had recently embraced Islam in a pivotal turning point in world history.

Behind this image of the Prophet Muhammad receiving his first revelation lies a profound history of cross-cultural dialogue and rapprochement between the Mongols and Islam. The image illustrates the expansion of Islamic boundaries of acceptance to meet Mongol rulers’ expectations in medieval Iran, while also emphasizing the inculcation and communication of core Islamic beliefs like the finality of Muhammad’s prophethood. Far from being Islamophobic, the image reveals a pivotal moment in Islamic history when the faith was adopted and re-imagined for the Mongol rulers as they integrated into Iranian society. Exploring the context of the image’s emergence – and the world it was a part of – is key to understanding the historical evolution of the Islamic world and its accommodation with different contexts and rulers.

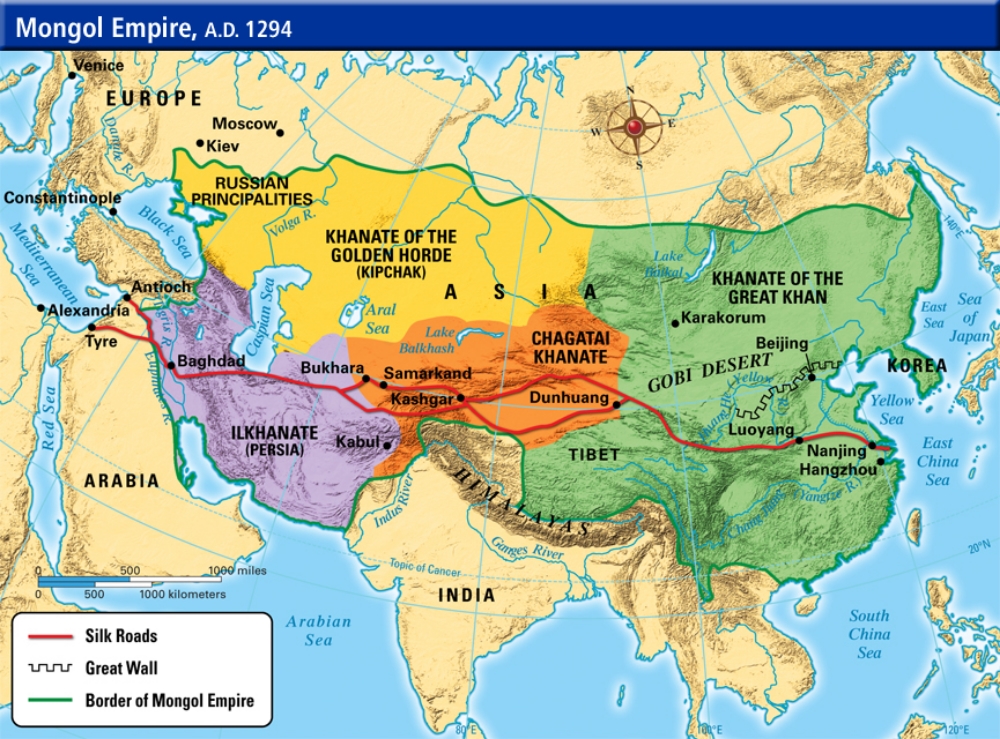

Established by Chinggis Khan and his successors in the early thirteenth century, the Mongol Empire at its height stretched from Korea to Hungary, and from Iraq to Siberia, fostering remarkable mobility across Eurasia as it bridged diverse cultures. This cultural and material exchange continued even after the Mongol Empire split into four separate khanates, centered in China, Central Asia, the Volga area of what is now Russia, and Iran. This last khanate, known as the Ilkhanate, dominated the eastern Islamic world for nearly a century, encompassing modern-day Iran, Iraq, Azerbaijan, and parts of Turkey. While the Mongol conquests have been associated in modern perception with large-scale destruction and violence, the empire established by the Mongols also facilitated extensive cultural and material exchanges.

Mongol-ruled Iran, especially the city of Tabriz, became a hub for a trans-Eurasian transmission of knowledge, especially between China and the Islamic world. The Mongols collected diverse knowledge experts and technologies at their courts, spanning the fields of astrology, medicine, history, and geography, as well as different religious representatives and diviners. It was in this context that Rashid al-Din (d. 1318), a Persian Jewish physician who converted to Islam, rose through the ranks to become an influential vizier.

Rashid al-Din’s access to a diversity of new, written and oral accounts from throughout Eurasia played a key role in his authorship of the Compendium of Chronicles. His sources included Buddhist monks, manuscripts in Sanskrit, Latin, Hebrew, Chinese, Arabic, and Persian, and Mongol oral traditions as well as Mongolian royal archives. Chapters in the Compendium cover topics ranging from pre-Islamic Iran and the emergence of Islam to Europe, China, and the Mongols.

Most information would have been new to the readers. A chapter on India, for example, included the most informed and accurate description of the Buddha’s biography and Buddhist dogma to date in the Islamic world. Rashid al-Din deliberately maintained the often-contradictory historiographical perspectives of the Mongols’ diverse subjects, creating parallel chronologies. The Compendium’s manuscript was completed during Rashid al-Din’s lifetime, likely in his own scriptorium in Tabriz, and possibly under his supervision. Enabled by this new phase in Eurasian interconnectedness under Mongol rule, the Compendium showcased the Mongols’ ambitious vision of universal domination. It was written shortly after the court’s official adoption of Islam and was strongly informed by the gradual process of reconciliation between Islam and the Mongols.

In her book on visual representations of the Prophet Muhammad, art historian Christiane Gruber demonstrates that illustrations of the Prophet as a divinely appointed military and political leader in the Compendium were meant to resonate with the Mongol rulers’ ideological conception of Heaven’s choice of Chinggis Khan. The Mongols argued that Eternal Heaven (Mongolian, tenggeri), their supreme sky deity, granted Chinggis Khan its blessing and protection, and an exclusive mandate of universal domination. The Mongol rulers of Iran would have therefore found parallels between their conception of heavenly support of the royal household and this visual representation of divine support for Muhammad. Muslim artists sought to craft Islam’s sacred narrative in a way that would be compelling from a Mongol perspective.

These images are just one aspect of a broad set of cross-cultural “dialogues” that took place between Muslim and Mongol worldviews in the decades following conversion. Rashid al-Din was at the center of these Muslim efforts toward Mongol acculturation. And the Prophet Muhammad had a profound role, not only in this world history, but also in Rashid al-Din’s philosophical and theological treatises. Developments in Islamic theology (Kalam), specifically its reconciliation with Greek-derived philosophy through the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, contributed to the emergence of a new philosophically-informed discourse of the Prophet as possessing the perfect human soul and enlightened intellect.

These developments provided both a common ground for interfaith debates and further galvanized the arena of religious disputation between Muslims, Jews, Christians, and possibly even Buddhists. The latter had arrived in Iran from Buddhist centers of learning across Eurasia to benefit from Mongol patronage and sought to win the rulers over to Buddhism.

Rashid al-Din’s treatises represent the intersection of these broader intellectual-religious developments in the eastern Islamic world with the Mongol court’s dynamic religious environment that fostered interfaith competitiveness. The khans were keen on hosting interfaith debates. These provided the khans entertainment, an opportunity to evaluate the clergy and scholars visiting their courts, and to demonstrate their own intellectual fortitude. Many of Rashid al-Din’s philosophical and theological treatises are framed as answers to questions posed to him during or following such court sessions.

They represent the remarkable cultural and religious diversity of Mongol-ruled Eurasia, including Sunni and Shiʿi Muslim scholars, Christian and Chinese physicians, and Buddhist monks. Questions were also posed by the Mongol kings themselves, especially by the vizier’s patron Sultan Öljeitü. His interest in religions is demonstrated by the religious transformations he underwent: from his Christian baptism in infancy and his Buddhist education to his conversion to Sunni Islam (first as a Hanafi, and later, Shafiʿi) and finally his conversion to Twelver Shi’ism.

The theological works of Rashid al-Din demonstrated not only his commitment to disputing other religions, especially the reincarnationist Buddhists and fellow Jews, but also his ongoing endeavor to acculturate the Mongol elite to Islam. He sought to creatively inculcate in his Mongol patrons new, monotheist religious sensibilities by presenting Islamic beliefs in a way that would resonate with Mongol perspectives. The Prophet Muhammad figured in this prominently.

One of Rashid al-Din’s most extensive treatises emerged from a court debate concerning Muhammad’s reception of revelation through the angel Gabriel, the same scene the Compendium’s illustrators portrayed, and the same image used at Hamline University. This debate took place in 1307 at the Sultan Öljeitü’s camp, where Muslim scholars gathered following Öljeitü’s invitation. When the ruler asked them why Muslims consider Muhammad the most perfect prophet, their answer was that messenger prophets (rasul) like Muhammad received revelation through the mediation of angels whereas inferior prophets (nabi) received it directly, without angels’ mediation. Öljeitü then asked what made revelation through intermediacy better than unmediated revelation.

According to Rashid al-Din, Öljeitü made brilliant comments during these audiences that often left scholars speechless, despite the Mongol Sultan being illiterate and a recent convert. Caught off guard by this question, the scholars asked for time to consult. Öljeitü decided to have fun and turned this into a contest: the scholars were asked to compose one answer, while Öljeitü, with the aid of Rashid al-Din, composed the other. The best answer would grant the victors an honorary robe from the losing party. The result of this wager is Rashid al-Din’s, or rather Öljeitü’s, Book of the Sultan, a long treatise covering the ranks of the prophets, differences between revelation and inspiration, proofs of the finality and superiority of Muhammad’s prophethood and more.

Did this exchange take place the way Rashid al-Din described it or was it a figment of his imagination? It is hard to tell. Instead, we might view these “dialogues” as reflecting the interactions between two patterns of thought. Specifically, these “conversations” demonstrate that when they officially embraced Islam at the turn of the fourteenth century, the Mongol rulers came with certain expectations. They expected that their own sacred status as the descendants of Chinggis Khan would be accommodated and reinforced by the new religion they adopted. To secure the Mongols’ conversion to Islam, Muslim cultural brokers such as Rashid al-Din accommodated certain Mongol expectations. They skillfully utilized an array of Islamic and Persian religio-political resources while demonstrating an in-depth familiarity with Mongol tradition.

How did the question of direct or indirect prophetic revelation relate to the Mongol acculturation to Islam? The Mongols held that Chinggis Khan and his successors possessed a special affinity with tenggeri, their sky-deity, and moreover, directly communicated with it. The question about communicating with the divine therefore held great significance from the Mongol perspective. If Muhammad was the supreme prophet, as Muslims believed, he must communicate directly with the divine as Chinggis Khan had done, according to their beliefs. Indeed, in the Book of the Sultan, we learn that Muhammad had both indirectly communicated with the divine through the angels, and directly, for example through his heavenly ascension.

Rashid al-Din did more than appease his Mongol benefactor regarding the preeminence of Muhammad. He used this inquiry to assimilate Öljeitü’s own sacral status into Islam, making room for the Mongol kings in Islam’s religio-political hierarchies.

The discussion of the proofs of Muhammad’s prophethood in the Book of the Sultan is prefaced by an introduction that explores the proofs for Öljeitü’s own sacral rank as a uniquely fortunate, miracle-working-saintly king. In this work, Öljeitü becomes a sultanic simulacrum of the Prophet Muhammad based on the Mongol ruler’s own rationalist intellect and divinely granted inspiration. Öljeitü’s own lack of literacy, like Muhammad’s, is presented as a marker of his divinely-given intuitive knowledge. On coins, Öljeitü’s name appeared as Muhammad Khudabanda (meaning God’s servant).

This fusion of theology and sacred kingship was reaffirmed in the treatise’s overall layout. The Book of the Sultan begins with the story of Öljeitü’s miraculous birth, which ended a severe drought, and concludes with another treatise regarding the afterlife and the resurrection that describes the remarkable fate awaiting Öljeitü’s illuminated soul. Öljeitü’s exceptional life cycle and the proofs of his sacral royal status frame the discussion of Muhammad’s prophethood.

Rashid al-Din crafts for his Mongol patron a remarkable position of Islamic sacral kingship. But he also asks for something in return. There is a price for this generous Islamic “concession” to the ruler’s expectations of a sacral rank. The Mongol rulers can be sacred kings but never prophets. They must accept the core Muslim belief that Muhammad was the final prophet. Indeed, one of the primary objectives of the Book of the Sultan was to inculcate the idea of Muhammad’s distinctiveness from mankind – prophets or kings.

Returning to the illustration of the Prophet receiving his first revelation, we can now start to identify a dialogue taking place between the Mongols and Islam. On one hand, these images ingeniously repackaged Muhammad’s monotheistic message in a manner that resonated with the Mongol perspective. Muhammad was presented as a divinely assisted mythical hero setting on his triumphant quest to propagate the faith, making it easier to draw parallels with the figure of Chinggis Khan. On the other hand, the images also educated Mongol viewers about central precepts of Islam including the place of mediated revelation in the emergence of Islam. Through this visual focus on Muhammad, they also reaffirmed, visually, his place as the final prophet, a rank that neither Chinggis Khan nor any other Mongol sacred king could surpass.

Behind the image of Muhammad’s revelation lies a story of inter-religious and cross-cultural translation and exchange spanning the Eurasian expanse. This story rightfully belongs in any world history curriculum.

1 comment

Thanks for this excellent summary. Oljeitu wasnt only talking (via Rashid al din) to the mongols, and it wasnt only in city of Tabriz – im sure you already know about soltanieh – largest possible brick dome, early double dome , influence for so many buildings, hugest possible ambition in originally wanting key shia tombs relocated there – is it sited in fertile plain for horse grazing?

and then theres OLjietu’s wondrous stucco mihrab in the ancient friday mosque in Isfahan. this mosque tells the architectural history of persian power (until Shah abbas’ new complex including a new friday mosque nearby). and oljietu’s mihrab manages to be both supremely delicate – and overwhelming – its not possible to just walk past it – you have to stand and stare and stare and try to drink it in!