The following is an article by Evlin Hüseyinoğlu, a computer engineer from Antakya. After her home town was destroyed by earthquakes, she joined Nehna to strengthen long-term relief efforts. She developed the Nehna project Beledna – Hafıza Haritası in 2023.

On February 6, 2023, two earthquakes occurred centered in Kahramanmaraş, Turkey. Measuring 7.8 and 7.5 magnitudes, they happened 9 hours apart and were felt in Turkey, Syria, Cyprus, Lebanon, Iran, and even Jordan. They resulted in approximately 350,000 km2 of damage and affected around 14 million people. More than 39,000 buildings collapsed on the first day alone, including many historic structures in Turkey. It is stated that 35,355 buildings collapsed, 17,491 buildings needed to be urgently demolished, 179,786 buildings were severely damaged, 40,228 buildings moderately damaged, and 431,421 buildings sustained minor damage. After the disaster, more than 2 million people faced housing problems and at least 5 million people migrated to different regions. Official figures report at least 53,537 deaths in Turkey and 8,476 deaths in Syria.

The sentences above describe the physical damage and financial devastation caused by the earthquake. But these numbers are inadequate in conveying the extent of the changes those of us who lived through it experienced.

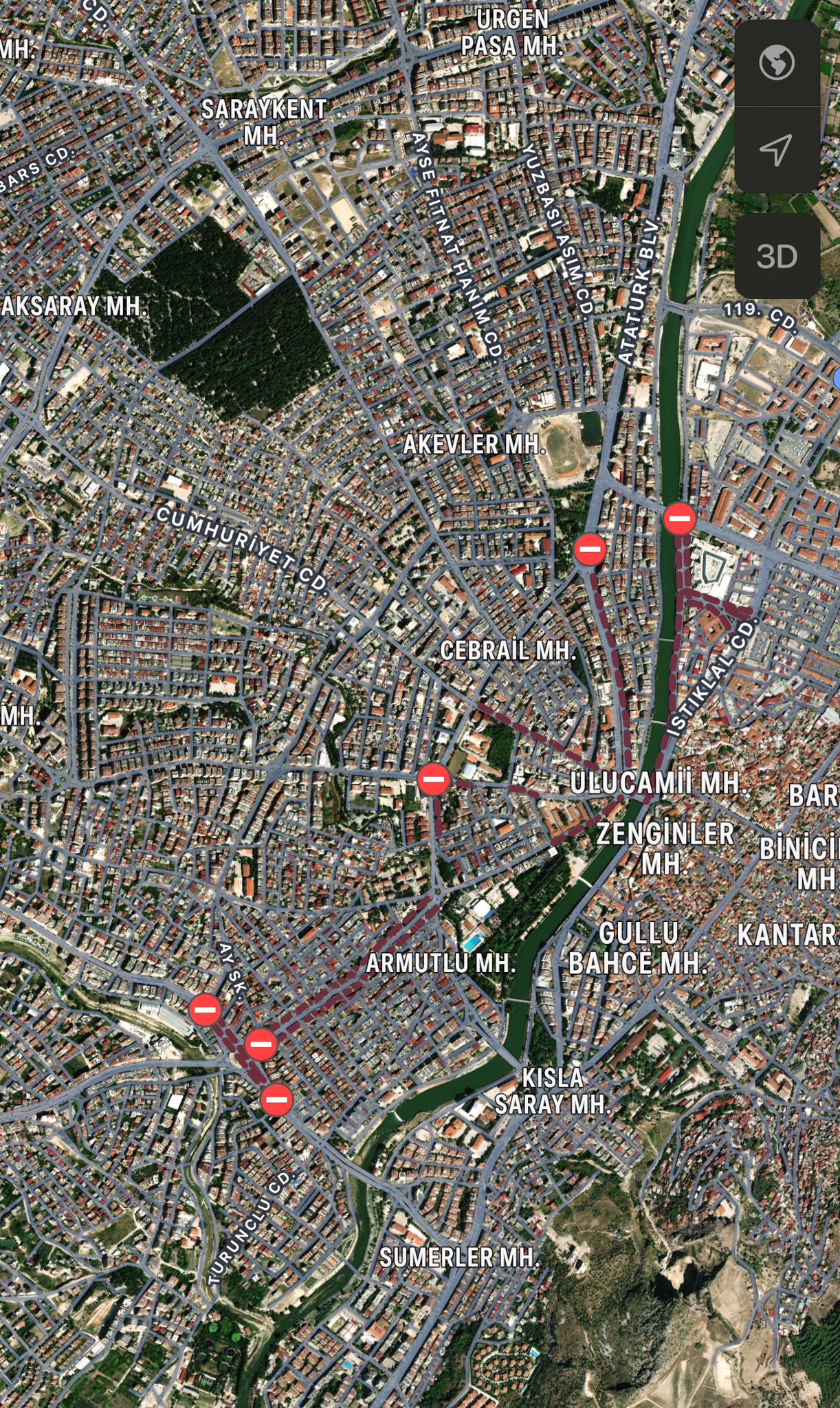

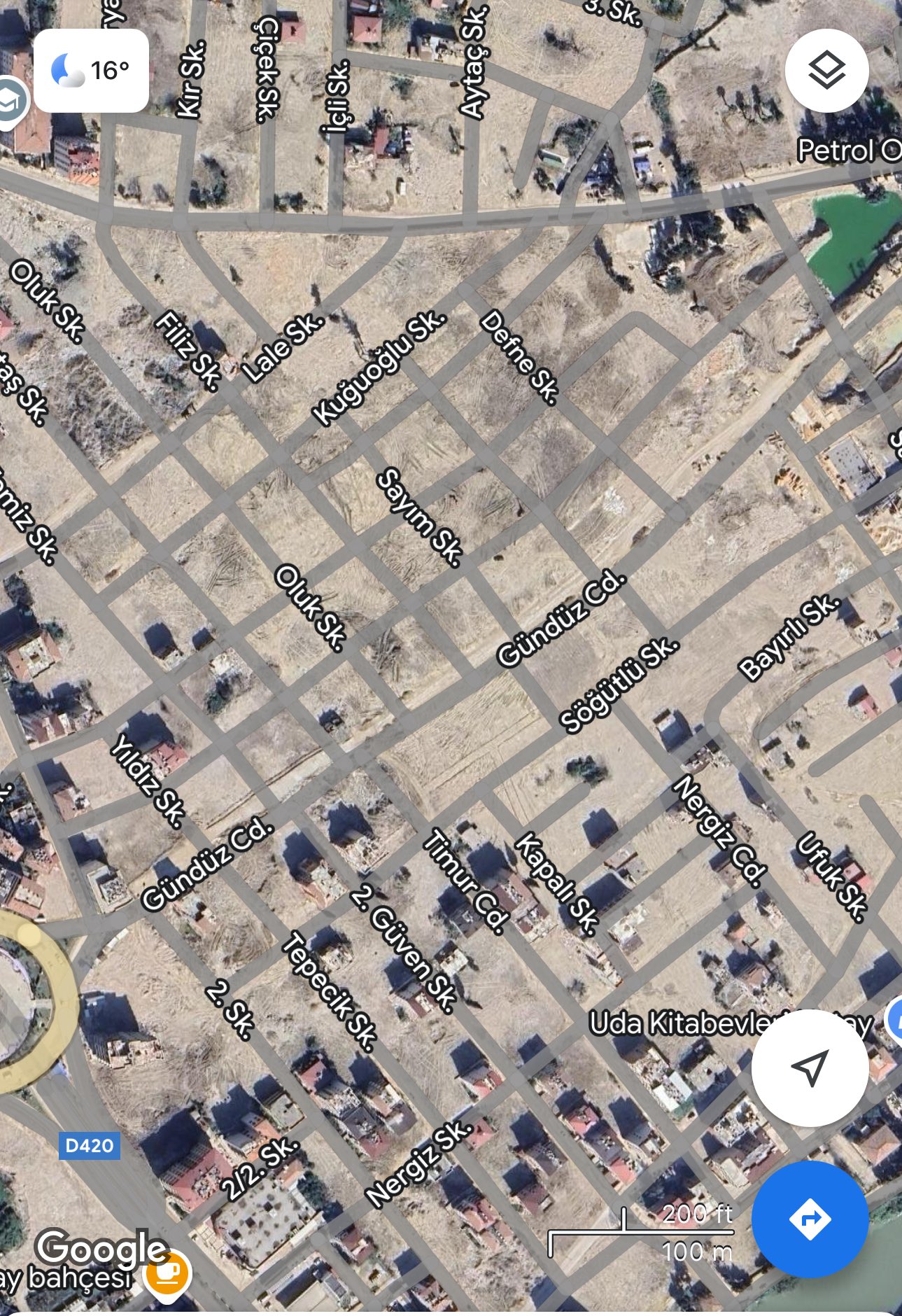

Antakya, my hometown, wasn’t just devastated; it was fractured. Over 70% of the buildings downtown were rendered unusable, leaving gaping holes in its heart. This city, synonymous with cultural diversity in Turkey, suffered a heartbreaking blow to its magnificent heritage. Imagine churches, baths, mosques, synagogues – places of worship that stood side-by-side for centuries – reduced to piles of rubble. Byzantine walls, caravanserais, even Roman aqueducts, all whispered testaments to a rich past, now lay silenced.

But Antakya wasn’t just about grand structures. It was the everyday tapestry woven from its people. We, a vibrant mix of Christians, Muslims, and Jews, grew up alongside each other in a unique social fabric. Imagine sprawling courtyard houses, their long tables a constant invitation to family, friends, and neighbors. Imagine the melodic lilt of Arabic intermingling with Turkish in the bustling streets. This was the essence of Antakya, a symphony of cultures tragically disrupted.

The earthquake may have destroyed many buildings, but it hasn’t erased our memories. We are rebuilding, yes, but our city is more than bricks and mortar. We’re rebuilding our lives, our communities, and most importantly, salvaging the irreplaceable fragments of our shared past.

Before the earthquake, I was involved with Nehna, a platform for the Orthodox Christian community in Turkey. We focused on intellectual pursuits, preserving our culture, and fostering mutual understanding. But the earthquake forced us to shift gears. We became a lifeline, establishing soup kitchens and organizing events to support our displaced community. But the real challenge loomed – the future of Antakya. Reconstruction plans were being made, but we feared they might erase the very essence of the city. This is where our story takes a new turn. We created Beledna – Hafıza Haritası, a memory map, to ensure the reconstruction reflects the soul of Antakya, not just its physical form.

In this article, I’ll share with you the personal story of loss and resilience, the fight to preserve our heritage, and the hope we hold for a future Antakya – a city rebuilt, but not forgotten.

February 6

When I woke up around 05:00 on February 6 at my home in Ankara, I had received over 600 messages on my phone. I learned there had been an earthquake at around 04:00, and my family was physically okay. The first thought that crossed my mind was, “If the houses collapsed, everyone would have gone to the church.”

If you are an Orthodox Christian from Antakya, like me, you know that when a major event occurs, people gather at the church. We gather there not only for weddings, funerals, or hosting guests, but also in times of crisis. Even though the 1999 Adana earthquake hardly affected Antakya, most of the congregation stayed in the church for eight days out of fear of aftershocks. We went there without a second thought because it was our second home.

The Saint Peter and Paul Greek Orthodox Church, located at the entrance of Saray Street, – the heart of Antakya-was the physical heart of our community since it reopened in 1889 following destruction in the 1872 earthquakes. Two magnificent gardens surrounded the church; meanwhile, the rooms and kitchen opening to the garden reflected the importance of courtyards and kitchens in Levantine architecture, shared between Antakya and cities down the coast like Beirut and Jaffa.

You can understand from my use of the past tense that we lost the main place that held our community together in the recent earthquakes. Therefore, it was not easy to cope with events that occurred during or after the earthquake because of this great loss.

The Essence of Antakya

The part of the city between Saray Street and Kurtuluş Street embodied the essence of Antakya. Saray Street starts with the Orthodox Church and ends with the Ulu Camii (Ulu Mosque). If you venture into any side street and head towards Mount Habib-i Neccar, all paths will lead you to Kurtuluş Street.

In this area, known as ‘Old Antakya’ by locals, all houses are organized around a central courtyard (avlu in Turkish or havush in Antakya’s Arabic dialect). Before transitioning to apartment living in the 1980s, large families used to live in these houses. I have always believed that the people of Antakya are fond of gathering around large tables because they were accustomed to living in houses with shared dining rooms and kitchens.

Those who have had the chance to stroll from Old Antakya to Kurtuluş and witness the lively life in the area know that the courtyards you see through open doors invariably have a citrus tree, potted flowers, and vines. When you make eye contact with someone inside, you are always greeted, invited in if you are recognized, and served coffee immediately. As you walk through the narrow cobblestone streets, the air is perfumed with familiar scents such as jasmine, pepper bread (biberli ekmek – similar to Lebanese man’oushe), and coffee.

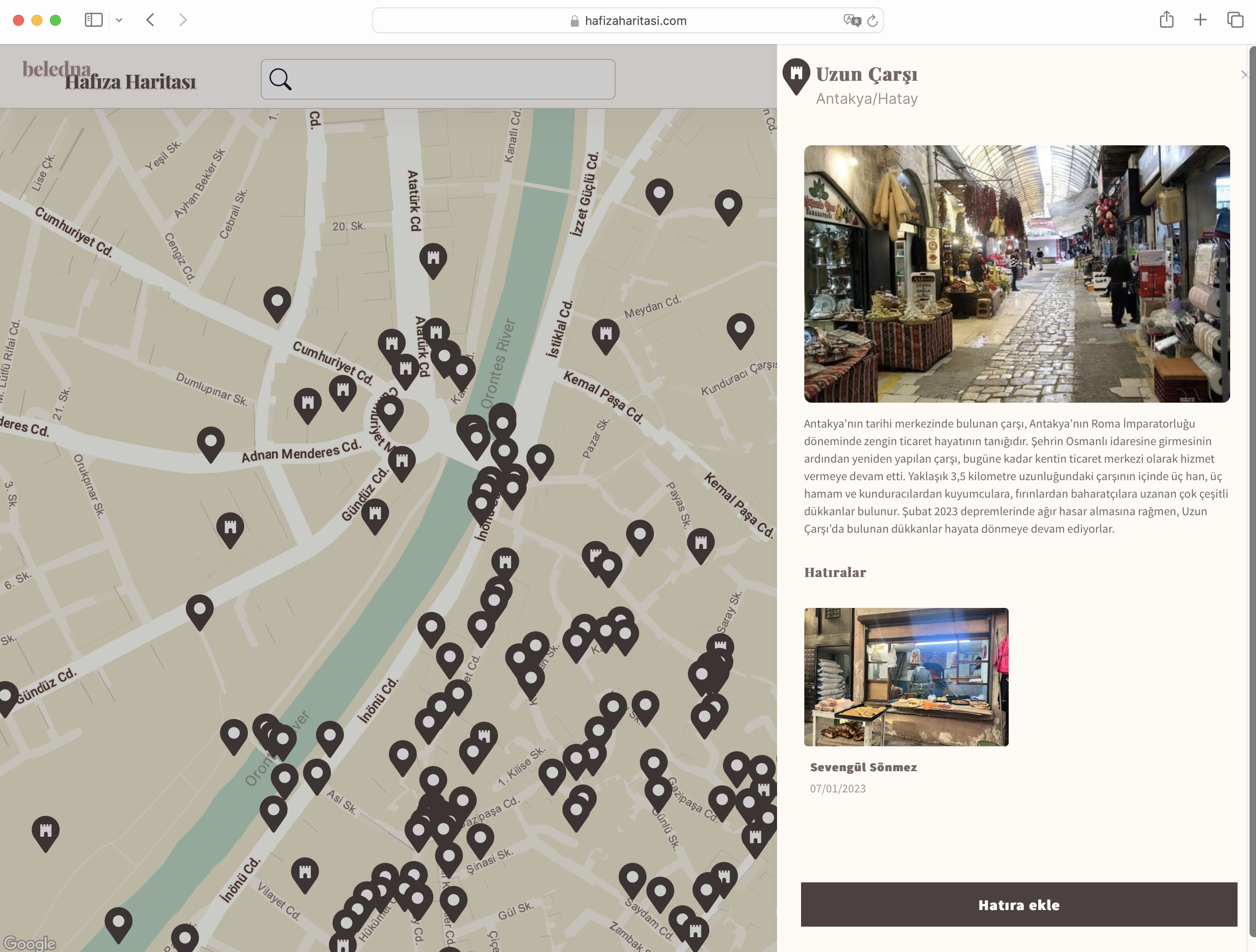

Upon reaching Kurtuluş Street, Mount Habib-i Neccar winks at you behind the chaotic traffic of Antakya. If you continue towards the mountain on your right, you find your way to Uzun Çarşı. Known as Souq al Taweel by locals, Uzun Çarşı bears witness to the vibrant trading life of Antakya during the Roman period. After the city fell under Ottoman rule, the market was rebuilt and served as the city’s commercial center until the earthquake. The souq, approximately 3.5 kilometers long, contains three caravanserais, three baths, and a wide variety of shops ranging from cobblers to jewelers, from bakeries to spice merchants.

I have always felt lucky for having experienced the period before Old Antakya’s gentrification. I have not felt a similar urban texture and sense of community anywhere else in Turkey; however, it is no coincidence that I have encountered the same vibes in Aleppo, Damascus, and Beirut. It is just one of the many details that show how artificial the borders dividing us are. Our shared heritage, symbolized by the jasmine-scented courtyards where our ancestors sipped coffee for centuries, underscores our connected experiences and histories.

Life centered around courtyard houses has not only shaped the urban texture but also influenced people’s outlook on life. Residents of courtyard houses learned to cherish neighbors who shared common walls with them. In Antakya, where the walls of churches and mosques stand side by side, the walls of houses of families from different communities also stand side by side. Antakya differs from the rest of Anatolia, which has been increasingly homogenized into Sunni Muslim-Turkish culture by the state especially since 1914 but even more after the 1950s. In Antakya, it is not uncommon to find Sunni Turks attending church for a Christian neighbor’s funeral, inviting a Jewish friend over for iftar, or Alevis making vows at the church wishing for children after a long period of infertility. Such examples of interfaith solidarity and community spirit are nearly exclusive to Antakya and its vicinity in Anatolia.

During Christmas and Easter, the children of our community always invite their friends to celebrations at the church, and the holidays are celebrated together with collective joy and enthusiasm. I still remember my astonishment when I encountered a quiet Christmas celebration in Istanbul without “anyone from the outside” i.e., non-Christians. It isn’t surprising that the physical center of such an intertwined life is a church with a large courtyard.

On that morning of February 6, the heart of Antakya collapsed for me, and the ground beneath our feet slipped away irreversibly. Along with historic structures such as the Orthodox and Catholic Churches, the Antakya Synagogue, the Grand Mosque and Habib-i Neccar Mosque, Affan Coffeehouse, the Hatay Council Building, Ata College, and the streets of Old Antakya, suffered near-total destruction.

The physical destruction brought about a massive migration. About half a million people from Antakya and its surroundings migrated to other cities. This deeply affected our already diminishing communities. The last Jewish families in Antakya left, and only 20 Orthodox families remained after the earthquake.

Return and Reconstruction

In this bleak and seemingly hopeless situation, I decided to join the Nehna team to address acute needs. Engaging in efforts of return and reconstruction in the year after the earthquake helped me cope with my grief. Nehna is a modest online publication that focused on intellectual activities before the earthquake. It originally set out to give voice to our community through articles and interviews that describe the culture, language, beliefs, and relationships of the Orthodox community living in Antakya and its surroundings to the wider audience in Turkey.

The earthquake quickly changed Nehna’s focus. In the first days following the earthquake, our priority was to identify the urgent needs in the region and find solutions. The Nehna team led the establishment of two soup kitchens in İskenderun and Samandağ. The first pot in the İskenderun church began to boil at the 18th-hour post-earthquake. The soup kitchen in Samandağ continued to operate until June 2023. On the 40th day after the earthquake, commemorative events were held in Istanbul and Ankara to show solidarity with our community, which had not yet been able to return to Antakya. The prevailing mood during the 40th-day commemoration and subsequent meetings was the desire to be together and return to our homeland.

After these initial efforts, we shifted our focus to addressing medium and long-term needs. We had discussions with the Women’s Branch of the Antakya Orthodox Church, which used to organize two bazaars annually, at Christmas and Easter, and offer financial scholarships to students. However, the church’s collapse meant that these scholarships were at risk of being discontinued. In response, our community and the Women’s Branch organized two bazaars to bring people together and to provide a market for local producers. Through these bazaars, we were able to provide scholarships for 20 earthquake victims from not only our community but also for other residents for two school terms.

All these steps created solutions for immediate needs. But we realized that the real challenge lay in addressing long-term repercussions. The loss of lives and forced migration inflicted deep scars on our small community. My fellow citizens and I, shaken by the loss of their loved ones, also feel the threat of the disappearance of our cities and cultures. While searching for ways to return, we are also trying to find the energy to stand against an unfair reconstruction process.

Our resistance to the current reconstruction process is driven by a profound concern for preserving its historical, cultural, and social heritage. The earthquakes of 2023 not only caused physical damage but also deeply impacted the social fabric and identity of our city. Our primary concern is that current plans prioritize modernization at the expense of Antakya’s unique historical character.

The city’s architecture, with its blend of Byzantine, Ottoman, and Levantine influences, is a testament to its rich history and cultural diversity. However, there is a risk that new developments may disregard this heritage, leading to the loss of irreplaceable historic buildings and neighborhoods. Furthermore, the social dynamics of Antakya, characterized by close-knit communities and shared public spaces like courtyards, are under threat. The traditional courtyard houses, which once served as hubs for communal living and social interaction, are at risk of being replaced by modern high-rise buildings that lack the same sense of community and history.

Another major concern is the potential displacement of residents due to recent legislative changes that allow for the seizure of properties deemed at risk of collapse. This has raised fears that long-standing communities in Antakya, including Arabic-speaking Alevis, Greek Orthodox Christians, and other minority groups, may be forced to leave their homes and neighborhoods. We can see similar reconstruction efforts in other cities, such as Diyarbakir, where historic neighborhoods were transformed into tourist attractions, displacing local residents and eroding the city’s cultural identity.

We fear that Antakya may suffer a similar fate if reconstruction is not approached with care and respect for its heritage. In essence, our resistance is not just about preserving buildings; it is about safeguarding the memories, traditions, and identities that make Antakya unique. We believe that any reconstruction efforts must be guided by principles of preservation, inclusivity, and community participation to ensure that the city retains its character and remains a place where diverse communities can thrive.

Ours is not just an effort to bring back lost places; it is the desire and struggle to recapture the memory lost with the place.

We will return; but will the place we return to be the same as when we left? What does Antakya need to become ours again?

A Note Dropped in History: Beledna

Official historical writing does not treat politically disadvantaged masses kindly. With the destructiveness of the earthquake added to today’s political climate, efforts to erase our heritage seem more pronounced than ever. It is necessary to write history from the perspective of Antakya’s people.

Beledna – Hafıza Haritası (Memory Map) is an online memory project we created, shaped by user contributions. It takes the name Beledna, meaning ‘our homeland.’ Beledna is more than just an archive; it is a testament to our resilience and a platform for reclaiming our history and identity. It is a repository not just for the state to take notes from when rebuilding, but also a space for our community to exist in the archives, ensuring that our cultural heritage endures even if our physical presence is challenged.

Through Beledna, we aim to go beyond just reproducing space; we strive to create a living memory of Antakya, one that reflects the rich tapestry of our shared experiences, coexistence, diversity, and struggle. It is a space where every memory, every photo, and every story is a note dropped in history, reminding us and future generations that our homeland is a place of resilience, hope, and enduring memories.

On Beledna, people can add their memories in written and visual form and record the meanings of the places for themselves. We worked with expert historians to add verified details and photos of buildings in Antakya that have historical significance and are essential to the urban texture. In this way, we aim to prevent the spatial memory loss caused by the destruction and reconstruction of the city.

In addition to the physical elements that once constituted this city, you can also find pieces of everyday life on the map. People share childhood photos, their dogs on the streets, and sunsets on the way back to their homes. Each memory opens a way for Antakyans to leave a note in history from their perspective. Each memory reminds us that our homeland is not just a disaster zone; it is a place that continues to exist with a series of experiences, coexistence, diversity, and struggle.

Our words echo our unwavering commitment to our homeland and to rebuilding our community. As we navigate the complexities of reconstruction and the uncertainties of the future, we remember that our shared heritage and collective memories are the pillars upon which we will rebuild Antakya, ensuring that its rich history and vibrant culture endure for generations to come.

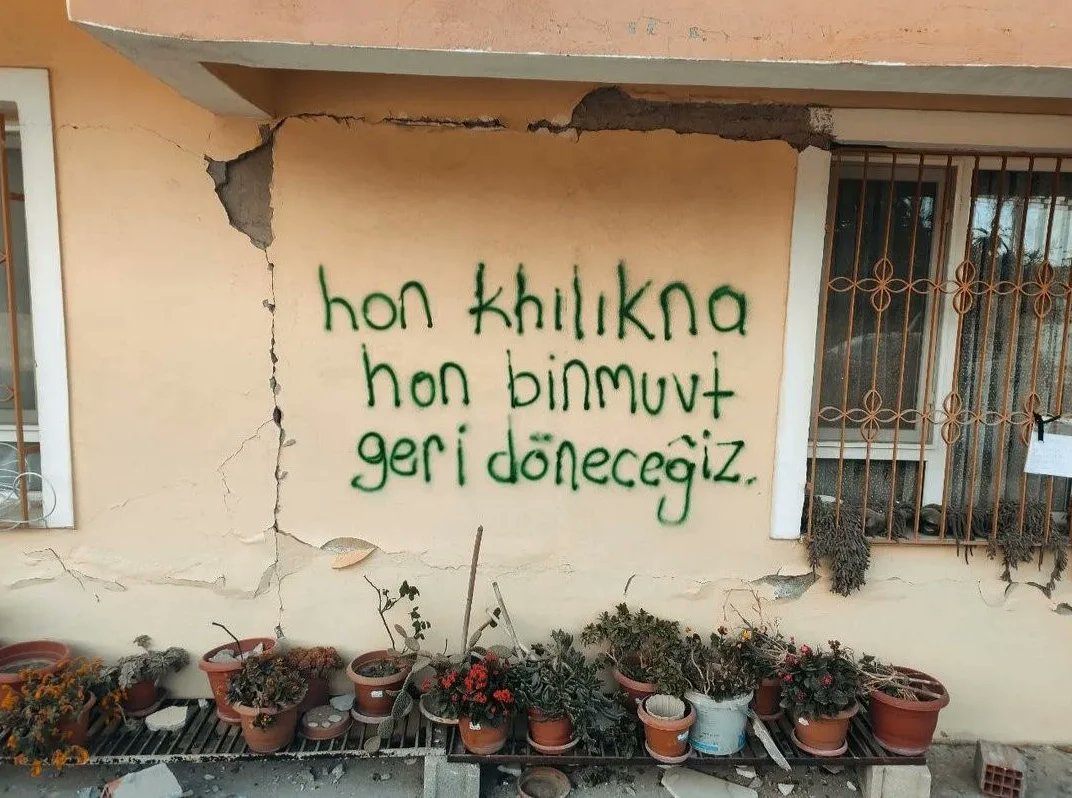

Hon khilikna. Hon binmuut. Geri döneceğiz.

We were born here. We will die here. We will return.