The following piece was written by Siavash Rokni, a postdoctoral researcher in Music Research at McGill University with a PhD in Communication from UQAM in Montreal. Siavash’s work focuses on popular music in Iran and the implications of musical hybridity following the cultural thaw during and after Khatami’s presidency.

***

Earlier this year, a Persian song from the 1970s went viral on South Asian social media following its appearance in a Bollywood film called Animal. Widely known as “Jamal Kudu,” the song appears in the wedding scene of character Abrar Haque to his third wife. A choir, including Iranian artist Tannaz Davoodi with a group of children, sing the song while Abrar dances, balancing a glass of whiskey on his head.

The scene is veteran Indian actor Bobby Deol’s return to the silver screen after decades of career decline. For the audience, his appearance is nostalgic as they see the return of their beloved Deol with great dance moves, lots of charm, and a catchy song, officially entitled “Abrar’s Entry.”

What’s striking about the viral Persian song, however, is that its lyrics don’t reference a wedding. Originally entitled “Ey Siah-e Zangi,” (“Oh Zanzibari Black”) the song is actually about an Afro-Iranian man who escaped from enslavement in Pahlavi Iran. Although many Indian viewers understood it as an Iranian folk song, in reality, it was written in the 1970s for a play that was never given permission to be shown in public. The song was later rebranded as a folk song despite not being one.

As the song went viral on South Asian social media, remixed and replayed with dance moves in over a million TikTok videos, the question of its original meaning and context was missed by the many people reposting it. Viral videos can tell us a lot about our society today and how things work, not only through what they show, but also in what is said or omitted about them as they circulate and are shared.

In this article, I first look at the song’s story and dig deeper into its history and implications. I then try to make sense of the significance of the virality of this song on South Asian social media and how it can provide new insight into the history of race in Iran.

The song was written by Ebrahim Shahdousti, a musician from Hormozgan Province in southern Iran. Shahdousti explains in an interview that he wrote it as part of a play about a man named Jamal, an enslaved person of African descent who he knew personally. Siah in Persian means black and Zangi refers to a person who came from the East African city of Zanzibar, one of the main ports where enslaved people were traded during the Indian Ocean slave trade. The Siah-e Zangi (Black Zanzibari) that the song refers to is Jamal, an Iranian of African descent who, according to Shahdousti, lived with a family that enslaved Jamal and treated him badly.

For centuries, Iran was home to a market of enslaved people from the Caucasus, Central and South Asia and East Africa. By the early 1800s, however, the slave trade in Asia had largely been curtailed, while the trade in enslaved people from Africa grew and became dominant in Iran until the British banned it in the 1850s. In this context, blackness became increasingly synonymous with enslavement. The slave trade was legally abolished in Iran in 1929. In the decades after, the memory of enslavement in Iran was largely erased from public consciousness, while Afro-Iranians faced discrimination. Shahdousti’s comments suggest that descendants of enslaved people remained in conditions of enslavement in Iran even many years after slavery’s formal abolition.

One day, according to Shahdousti, Jamal fled the horrific conditions he faced and was never seen again. The song is written from the perspective of Shahdousti, who lost his friend and wanted to bring attention to the continued existence of enslavement in Iran. At the time, he sought approval from Iran’s Ministry of Culture to perform the piece. However, the play was rejected by the authorities, and it was never performed.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1tFUylO9YIM?si=U3C1qQI5QaiyGI4L&t=99

No reason is given in the interview. One way to interpret this is to look at how the ambiguity in the government’s response was a power play that leaves the artist in limbo by not clearly articulating the reason behind the rejection. Another reading is to look at it from the perspective of what historian Beeta Baghoolizadeh describes as a “collective amnesia surrounding enslavement” in modern Iran whereby Iranian authorities, consciously or unconsciously, erase or downplay the history of enslavement in the country.

After the play was censored by authorities, Shahdousti decided to perform the song on its own with his band Leeva.

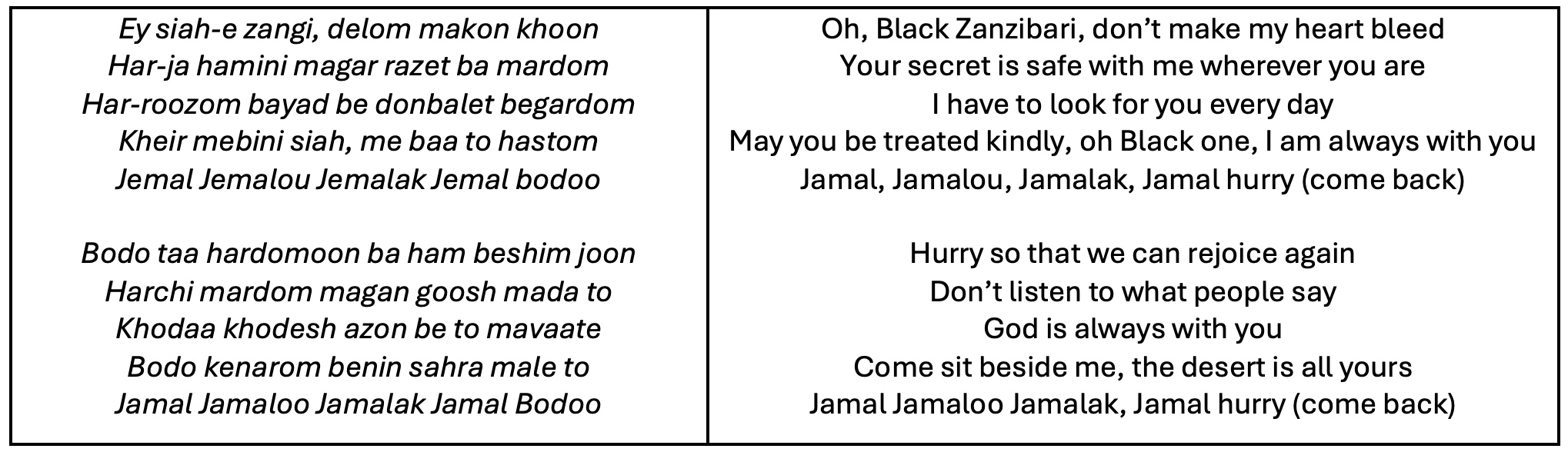

In the original version, after declaring that Jamal’s departure has made him sad, he sings that he is constantly looking for Jamal, hopes he is doing okay, and that he wants Jamal to come back:

Original version of the song with Leeva band:

Following its release, the song caught the attention of famous Iranian pop singer Zia Attabai, who covered it, changed its lyrics, and released it in an album with the theme of Iranian folk music.

The reasons for changing the lyrics seem to be multiple. For one, according to Shahdousti, many words in the original lyrics were not well understood because the song is written in the dialect of Persian spoken in southern Iran. Another reason given to Shahdousti was that the song sounded “nicer” or “better” in its new form. Shahdousti was not happy that singers took his song and changed it to the point that it lost its original meaning.

Moreover, many Iranians who were only exposed to the cover were never aware that the song was originally about enslavement.

Zia Attabai’s version:

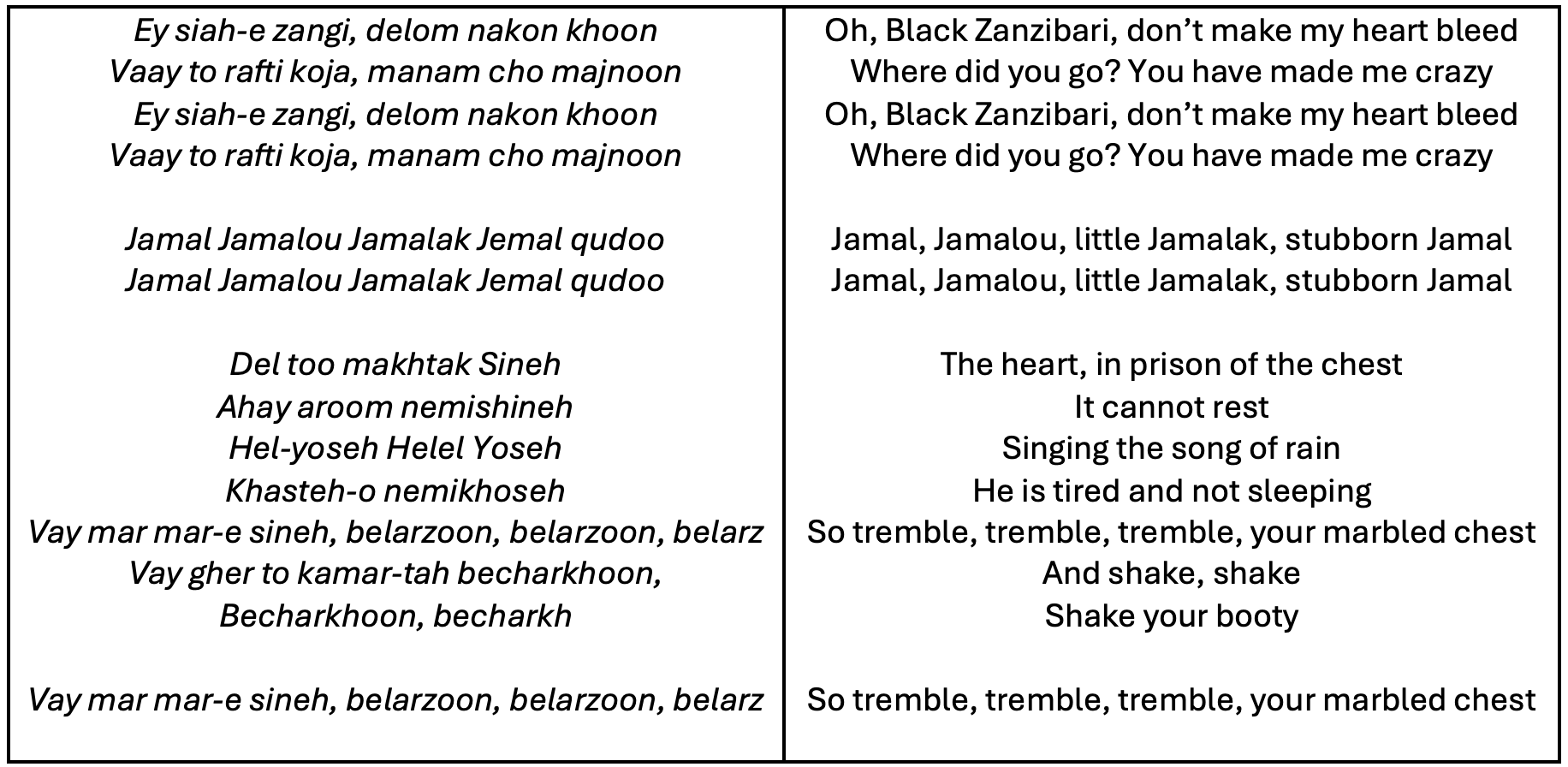

Following Zia’s remake, the Kharazmi Girls’ choir adapted his lyrics to create another rendition. This version was chosen and reinterpreted by the composer and music producer Harshavardhan Rameshwar in the film Animal. The lyrics of the song by Zia and Kharazmi Girls’ choir are as follows:

The inherent meaning and aesthetic of the song was changed to cater to the popular music market of the time. This entailed the exotification of the periphery for the pleasure of the center, as we see from the focus on dancing and singing. More importantly, we witness the erasure of the song’s original theme: enslavement.

In a recent interview with Cadence Music Magazine, Reza Koolghani of the band Damahi addresses this issue. Koolghani is part of a new generation of musicians from southern Iran whose music has become popular in Iran. Koolghani critiques the economic and cultural influence of what he terms the “center,” cities like Tehran and other urban hubs, in defining norms and trends in the Iranian music industry.

Both him and many other Southern Iranian musicians argue that the “center” favors certain aesthetics of the music of the south that reinforces their imagination of it.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jzYP857yysE?si=yWu50Ox4WN-DRFxP&t=618

In this way, music sung in Persian with an affected Jonoubi (southern Persian) accent is more economically viable, and hence accepted by the center, compared to the music sung in the actual dialect of the region. In other words, the center prefers their own “Bandari” vision of the south.

Interestingly, Koolghani covered Siah Zangi with his previous group, Darkoob Band, in their 2015 album where he sang the original lyrics of the song and credited Shahdousti in the album as the composer.

Cover of Siah Zangi by Darkoob Band:

Zia Attabai’s covering and changing of Jamal Jamalou was indeed driven by the market’s desire to fetishize the south. He was catering to a taste formed by exotification in the Iranian music industry in the 1970’s. This practice continued in the Tehrangeles music industry, as many so-called Bandari songs were sung by singers not from the region but who imitated the southern Iranian accent. For Attabai, a song about slavery was not going to be as appealing to the public as a love song from the south. Attabai himself is of Armenian descent, a minority group that was also at times enslaved in Iran prior to the bans in the early 1800s. Attabai’s intention was probably just to release a fun song that people would dance to, a goal he achieved.

When Shahdousti was asked what he thought of his song being used in a movie in India, he said he was unhappy because he was never recognized and compensated for his creation. Zia and many others took his song and freely reinterpreted it how they wanted. He also lamented that the song’s meaning and aesthetic completely changed. The song became an object of commercial success and lost its original intent: to show the brutality and heartbreak of enslavement in Iran.

It is likely that the Indian producers of Animal were unaware of the song’s original story and chose it merely because it sounded like a good fit for a wedding scene. In the version they chose, interpreted by Zia, the song has become a conversation between a lover and a beloved, rather than a tale of longing by a friend for a companion he has lost. But the song’s clear relation to the history of enslavement remains prominent in the song: the use of the term “Siah-e Zangi,” Zanzibari Black.

Jamal Kudu’s viral circulation in South Asian social media is likely due to an amalgamation of factors. For one, the song has an ability to connect with people from diverse cultural backgrounds due to its beat and melody. The song used in the movie Animal imitated the 1970’s recording and used audio production effects to reproduce the nostalgic feeling of an old recording even though the song was re-recorded in India for the movie. This nostalgic feeling may be part of the song’s charm and the reason it captivated audiences. The fact that the wedding scene featured Bobby Deol’s comeback as a Bollywood star likely also caught the attention of watchers and listeners.

The virality of this song did not start in 2023, as it initially became popular with Zia’s version in the 1970’s. The longevity of the song’s virality is due to the way the song was altered in different time periods to suit the changing market. The virality in 2023 brought back the already-changed song and gave it a new meaning for South Asian fans, as they associated it with their beloved actor’s comeback.

One of the functions of virality is that through repetition and circulation, it constantly shifts the meaning of a cultural artifact and gives it new meanings and purposes. This is not necessarily a bad thing, but in the process, it can also erase the stories the songs once contained.

At the same time, virality brings up another fascinating point. Until 2023, this song was a forgotten artifact of the past. The fact that I now write this article is because of the song’s new virality. When something goes viral, it piques the interest of someone like me to investigate and share it with others. This acts as a double-edged sword, as it evokes conversation but also creates new viralities of its own. In this case, the re-emergence of this song provides an opportunity to discuss an almost-forgotten part of the story of modern Iran: the history of enslavement and its continued legacy.