The following is a guest post by Soma Negahdarinia, an essayist and researcher. She is currently making a documentary about the history of Iranians in Istanbul. The first part of the documentary is available for viewing at the end of this article.

***

Once upon a time on the sea of Marmara, forty-six large commercial ships were docked off the shore. This was before the start of World War I, not far from Istanbul, and the ships were engaged in trade across the Mediterranean Sea. The ships’ names were inspired by Iranian cities; one was Isfahan, and among the others were Kerman, Kermanshah, and Yazd. The ships were docked with the raised Lion and Sun flag and the insignia: “Dersaâdet’in Acemleri” – Ajams at the Gate of Happiness, using an old term (Ajam) for Iranians.

Before I tell the story of the ships and their fate, I would like to say a little about that insignia: Dersaâdet’in Acemleri.

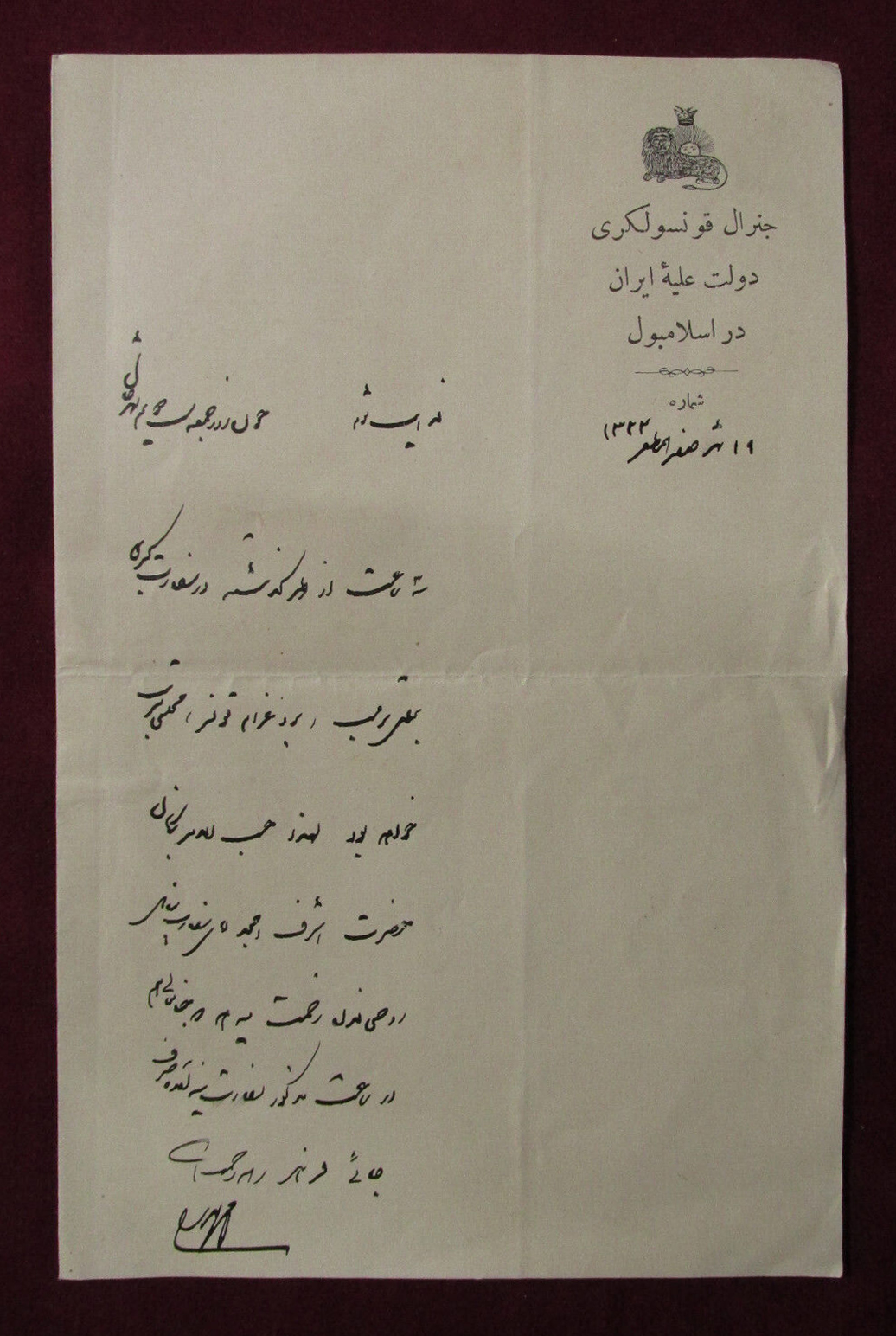

The insignia appears on many official letters, postcards, and old photographs from the period, and is originally a description that the Iranian diaspora in Istanbul used for themselves. “Dar e Saâdat” or “The Gate of Happiness” was the name that poets and travel writers first used in the 16th century to describe Istanbul, a city between two continents that reached the sea on all sides and that was the capital of the Ottoman Empire for centuries.

The Iranians who lived in Istanbul called themselves “Iranians at the Gate of Happiness” and I adopted this title to tell the story of the Iranian communities in Istanbul whose tale has been lost to time.

I started working on this project while conducting research at the Ottoman-era newspaper archives at the library of Istanbul University. During my research, I discovered articles from an Iranian newspaper. The Persian phrases resonated with me and I was drawn to the address listed on the newspaper’s front page as its place of publication. I had frequently passed that location on my way to the library, but I had never realized that a century ago, it housed the office of an Iranian newspaper. Fascinated, I went to Bâb-ı Âlî Street that same evening and searched for number 37. It was there that my project of uncovering the fragments of Iranian life in Istanbul began.

I worked on this project for more than two years and to complete it, I looked for everything from the past. In addition to examining archival documents, library sources and academic research, I read through the letters, telegrams, addresses, photo albums, songs, diaries and tombstones of the Iranians of Istanbul. I even completed some parts of the story with the help of antique dealers in Istanbul, who had many many letters, postcards and invitations from parties organized by Iranians in Istanbul.

فدایت شوم، فیالحال در صحت و سلامت کامل هستم، گلو درد من خوب شده و از فردا کارم در استانبول را از سر میگیرم

My dear, I’m currently in perfect health, my sore throat has healed and I’ll resume my work in Istanbul from tomorrow.

This telegram was sent in June 1909 by a person named “Ali Agha” to one of his dear friends in Tehran after an illness and in exile. This is one of the dozens of telegraphs that I found in “Galatasaray post office archive center” among the letters sent to Iran.

According to archival information, there were more than twenty thousand Iranians until the middle of the 18th century in Istanbul. These documents tell us how organized Iranians in Istanbul were, how they communicated with Iran, what institutions they had in the Ottoman capital, and what legacy they left behind.

History’s path cannot be followed like a continuous thread; with the passage of time, many narratives are marginalized or forgotten. As we reread historical narratives, their absences create a void. The story of the Iranians of Istanbul is one of these voids. The cultural, historical and social heritage of these people has been overlooked both in the collective dimension (organizations, institutions, and groups) and in the individual dimension (persons with political, social, and religious status).

On one hand, the collapse of the Ottoman Empire and the establishment of the Republic of Turkey in 1921, and on the other hand, the occurrence of two revolutions in Iran (the Constitutional Revolution and the 1979 Revolution) brought about major changes in the lives of Iranian migrants in Istanbul. These changes have not been extensively studied in the field of social sciences.

Consequently, for many Iranians currently living in or visiting Istanbul, there is no visible historical trace of this legacy. But in the Rare Documents Center of Istanbul University, there are many official letters that shed light on the unseen life of this large immigrant population in Istanbul.

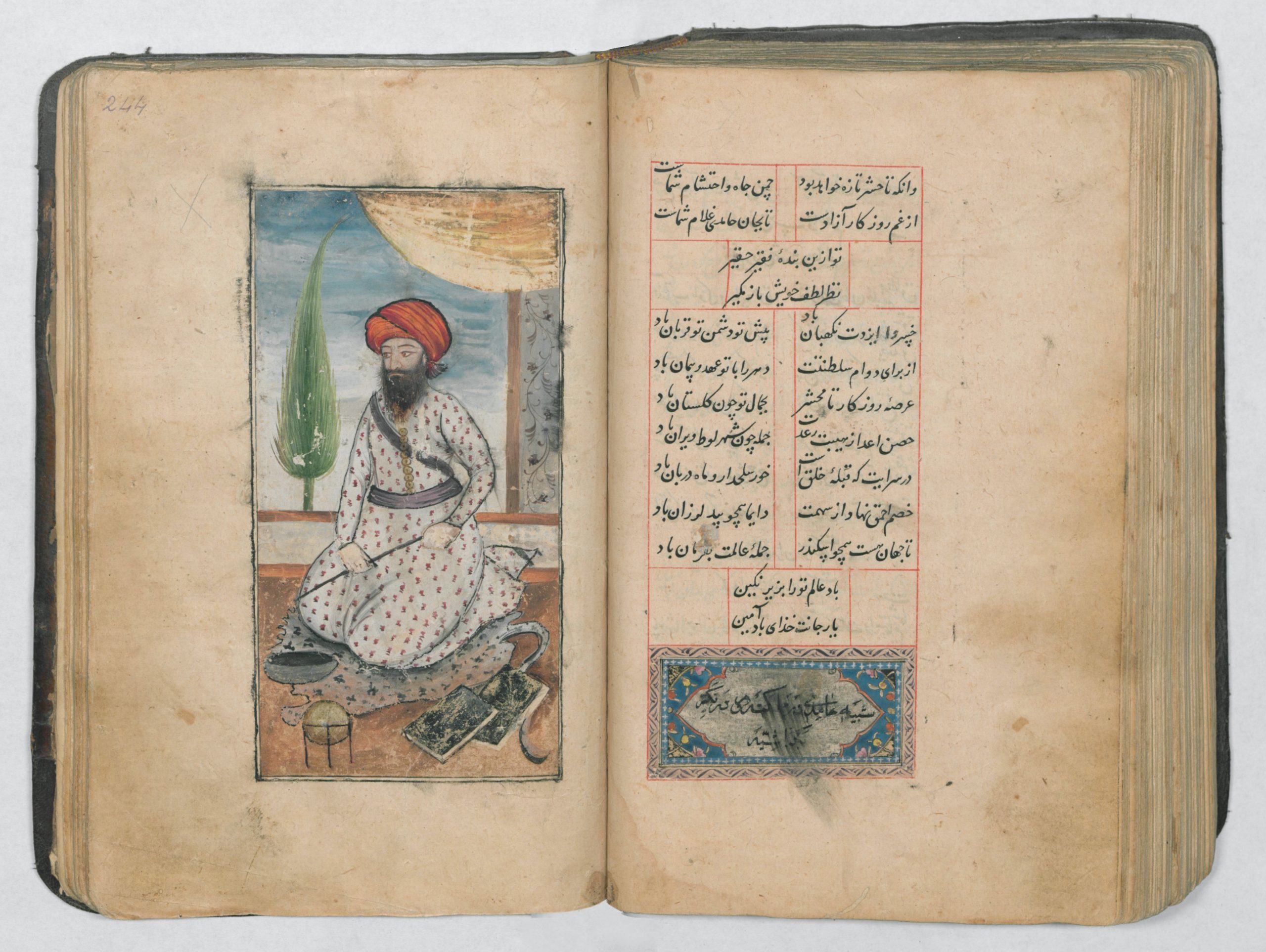

In my research, in addition to examining the social and political identity of Iranians in Istanbul through the dominant historical narrative, I have examined sub-narratives and through them I have explored the lifestyle, ceremonies, place of language and Persian literature, as well as the food culture of Iranians in Istanbul. These include the stories of Iranian confectioners in Istanbul who excelled in making pashmak (cotton candy) or the tale of the Iranian physician who cured Sultan Suleiman’s illness when all other doctors failed.

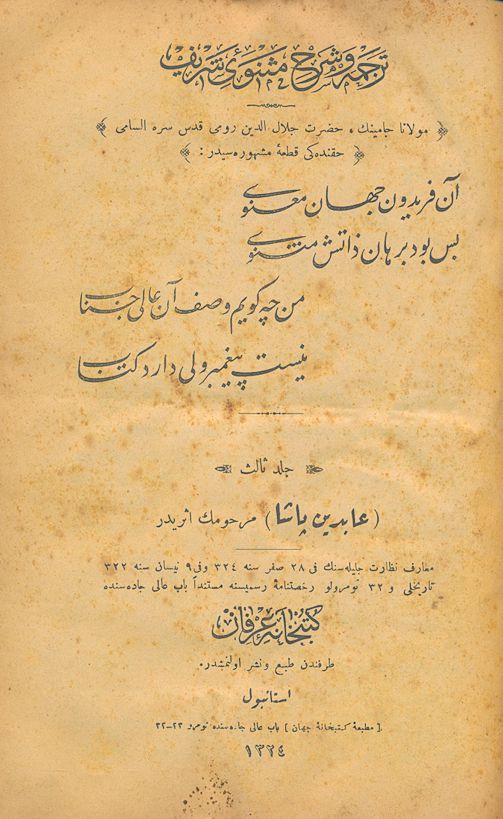

There is also the story of Iranian singers who performed in coffeehouses and were renowned among the people of Istanbul for their voices that resembled those of nightingales and birds – likely referring to a style of Iranian music performance in which the singer trills, known as “chahchahe” in Persian. And beyond this, there is the place of the Persian language in the Ottoman court and their collections of love and mystical poems written in Persian.

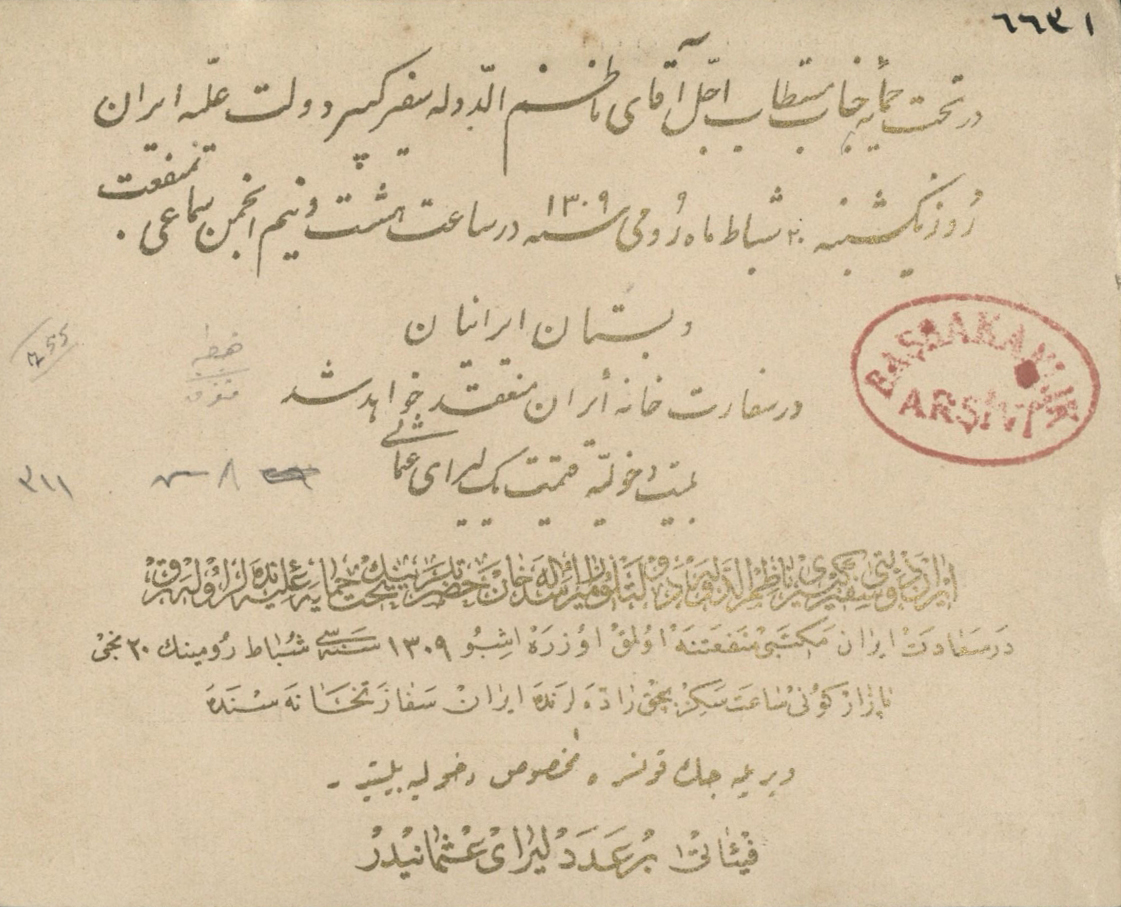

Now let’s go back to the story of the Iranian-named ships in Istanbul. In 1913, a famous businessman named Sokrat Atihidis Efendi, a citizen of Greek descent in the Ottoman government, went to the Iranian embassy in Istanbul and changed his citizenship to Iranian, for reasons unknown. He gave his 40 ships to the Iranian government and named his commercial shipping line after the cities of Iran. He employed many Iranians in his shipping company and despite the opposition and obstacles of the Ottoman government, he sent those ships to the Mediterranean Sea.

But the commercial voyages of these ships were short-lived. The conflict between allied European powers and the Ottoman government in World War l reached the Iranian shipping company and the British government targeted them on the sea for carrying war ammunition. In a short time, Isfahan, Kerman, Yazd, and Kermanshah were hit one after the other and crashed into the depths of the sea.

During the course of this research, I discovered dozens of stories similar to that of the Iranian Shipping Company in Istanbul. While these narratives provide valuable information about the social position of Iranians in Istanbul, they have been largely overlooked. This is because most research focuses on the political activities of Iranian immigrants in Istanbul, such as studies on the “Encümen-i Saadet” and the Shams newspaper, which organized constitutionalists worldwide during the Constitutional Revolution.

However, the lives of Iranians in Istanbul had significant social dimensions, and they were also very successful in organizing religious events like the Ashura processions and charitable associations. One notable example is the Iranian Charity Association of Istanbul, which held music concerts, theater plays, and dance performances at the Pera Hotel. The proceeds from these events were used to establish schools and provide scholarships to students.

I have collected these narratives and I will publish my research in the form of a documentary film in three parts. The first part narrates the life of Iranians in Istanbul from the beginning of the Ottoman Empire until the city’s occupation after the First World War, the second part focuses on the life of Iranians in the Republic of Turkey until the beginning of the 1979 revolution in Iran, and the third part deals with the life of Iranians in Istanbul in the contemporary era.

The research for the script of all three parts has been completed and the first part called “Little Iran” has been made. In it, viewers see the narrative of the important role of Iranians at the “Gate of Happiness,” the history of seven centuries of life of the Ajams of Istanbul. The documentary discusses artists on the scene of the “Pera Hotel,” the booksellers in the yard of the “Yeni Mosque,” the merchants in rooms of the “Valide Han,” the printers in the “Sahafan Bazaar,” and the politicians in the “Bâb-ı Âlî,” all of which are an inseparable part of the social and political history of Istanbul.

Through this documentary, we hope to shed light on a crucial part of the history of Istanbul and of the Iranian diaspora that has, until now, been overlooked.

For more information about the documentary, and to support our work, please contact us at: soma.negahdarinia@gmail.com.

References:

Sokrat Effendi submitted the letter of request for a change of citizenship to the Ottoman Ministry of Foreign Affairs in October 1912. For details, see:

BOA, BEO, 4148/311026, Lef 2, 12 Şubat 1328 / 25 Şubat 1913.

BOA, HR. SYS 2077/6, Lef 15, 16 Tevvel 1328 / 29 Ekim 1912.

To see more details about the sinking of ships belonging to the Iranian Shipping Company in Istanbul:

Han Melik Sasanî, age, s. 228-229.