The following is a guest post by Timur Khan, a Dutch-Pakistani researcher and PhD candidate at the Leiden University Institute for Area Studies. His research focuses on the Peshawar valley, its local communities and networks in the 18th and 19th centuries.

***

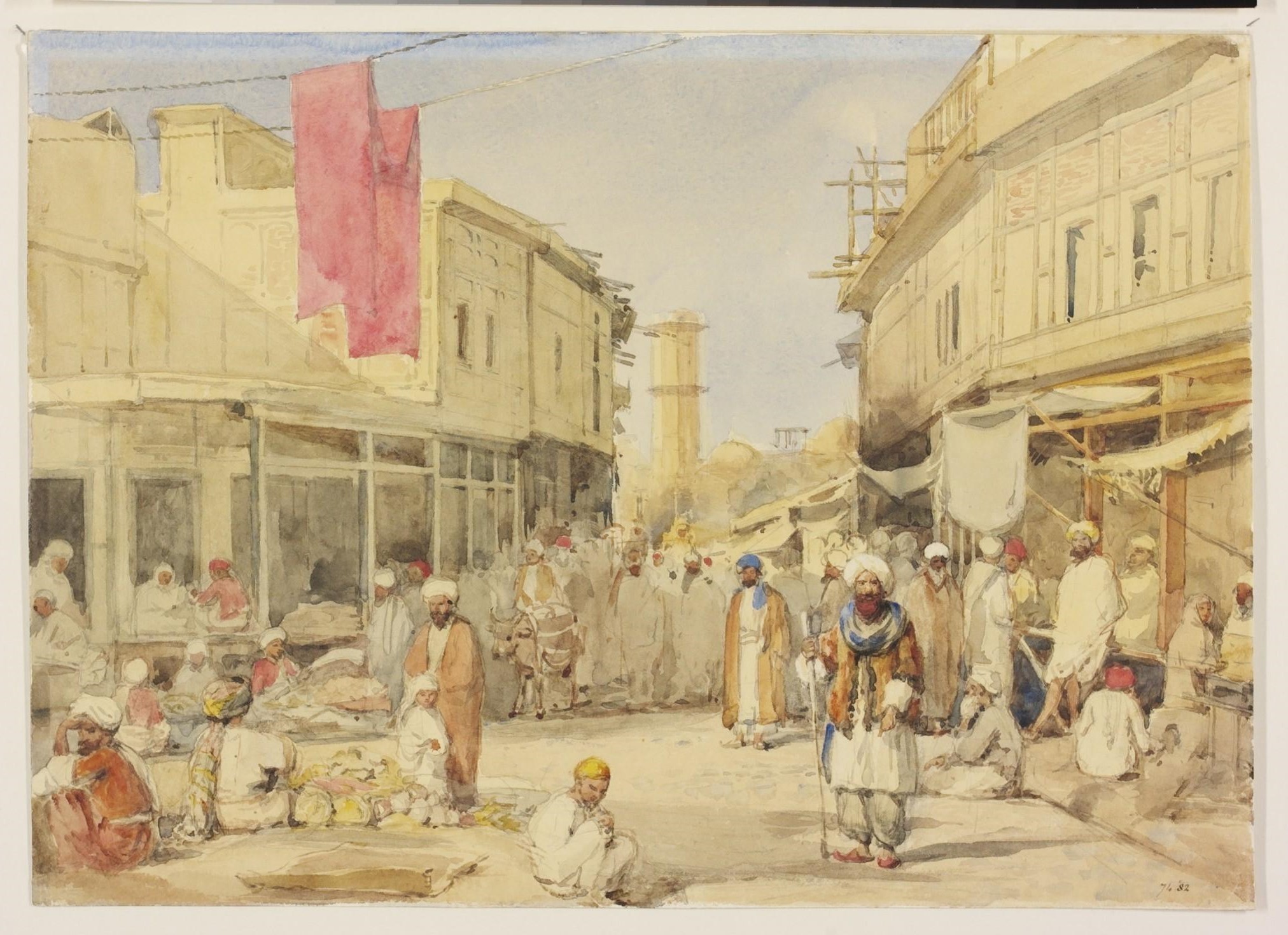

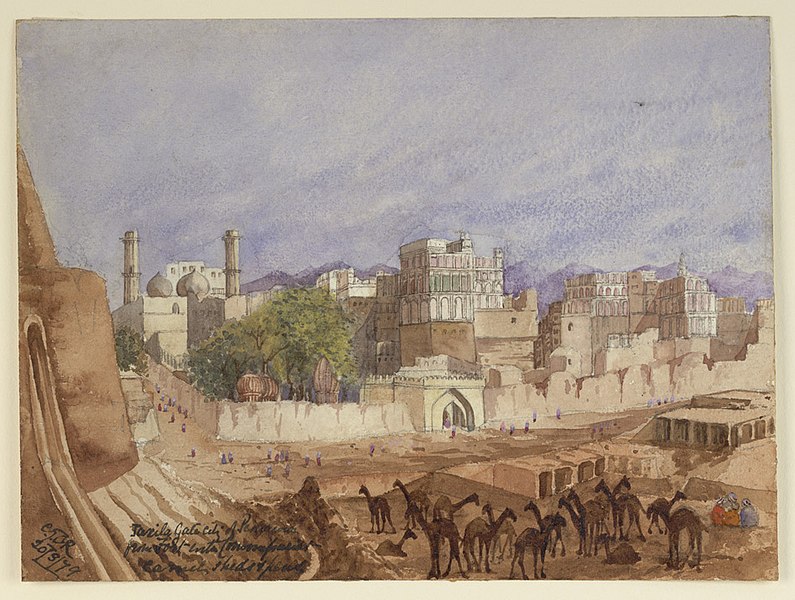

Heading east from Kabul two hundred years ago, crossing the famous Khyber Pass into today’s Pakistan, a traveler would be greeted by a broad verdant valley. At its heart stood historic Peshawar, a thriving trade center home to a multitude of peoples from Armenians to Kashmiris and languages from Persian to Punjabi.

In the open country outside its walls, Pashtun (historically called ‘Afghan’) communities held sway. South of Peshawar ran a river, the Bara, whose water irrigated fields tended by skilled farmers to produce a very special type of rice that shared the river’s name. Its grains, when taken from the reddish husk and cooked, were long and separated easily; they had a delicate taste and their fragrance filled a room – just the kind of rice you’d want for a pilau or biryani.

That rice has now vanished. Today, a different type — South Asian Basmati — is the preeminent long-grained rice the world over. But a traveler two hundred years ago could have sampled that Peshawari rice from the Bara, whose fame carried both east and west to Hindustan and Iran. Eventually, Bara rice was successfully planted in Iran in the late 19th century, giving birth to the famous Sadri strain which, unlike its progenitor, is still available. Like its parent, Sadri is prized for length, fragrance, delicateness, light flavor, and is used in polo and chelow.

Bara’s story is one of shared trade and culinary history between Iran and the subcontinent, and how that trade transformed in a new, colonial world economy. In British India, the new rulers were less interested in Bara rice cultivation than their predecessors, so it declined. By contrast, in Iran, Sadri growing expanded at the expense of other strains, as agriculture became commercialized and the country’s economy was forcibly pulled towards trade with Russia and the UK. In both cases, established grains declined along with old patterns of trade, making way for new ones — and reshaping the cuisines and diets of these lands.

Love for the long grain

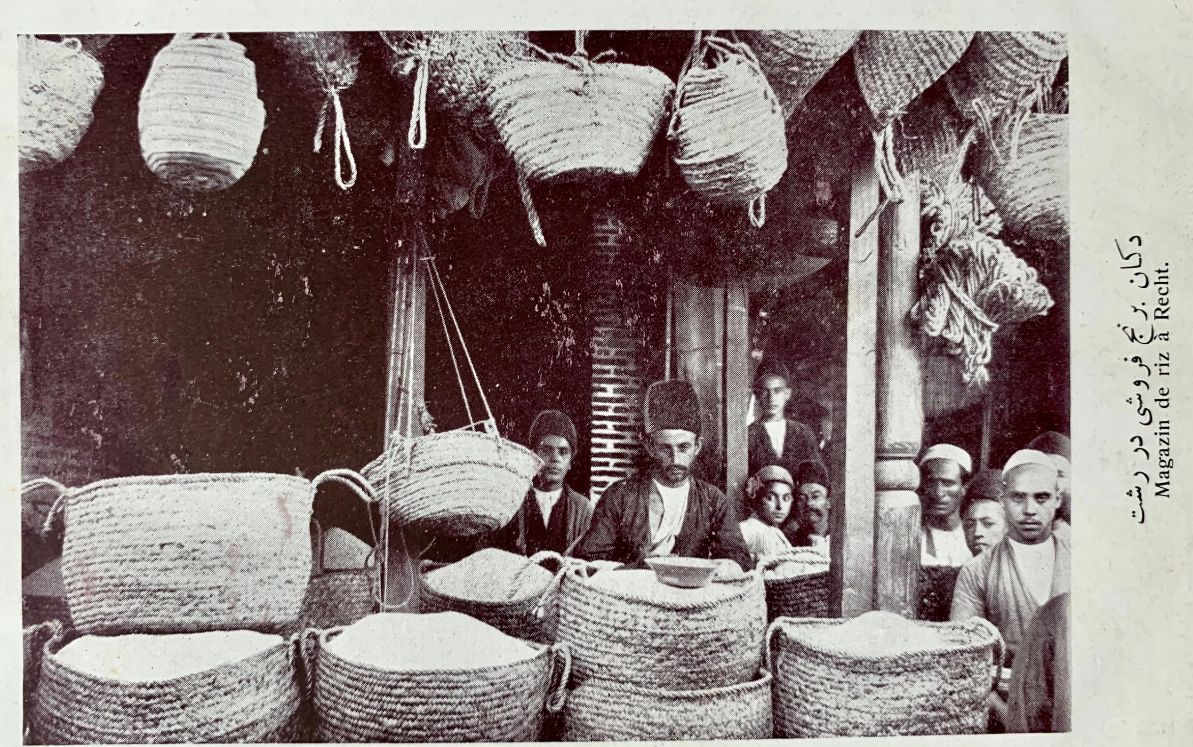

In a list of regional specialties being traded in late-19th century Iran, you would find some items familiar to readers today: Kashmiri shawls and Kermani cumin, for instance. Bara rice from Peshawar would also have been on that list. What made Bara rice so famous?

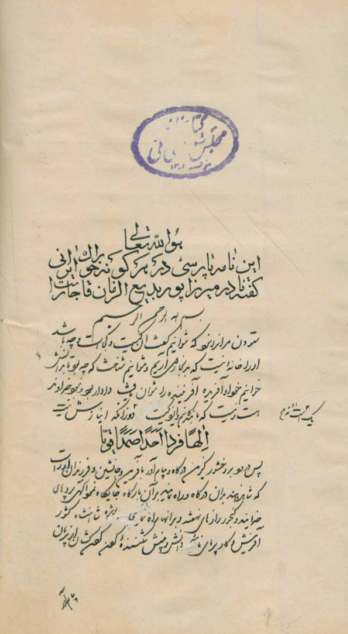

References to Peshawar’s high-quality rice go at least as far back as the 17th century, but the first detailed description I have found comes from a history of the Afghan Durrani dynasty, the Tarikh-i Hussain Shahi, written in 1798. Its author, Imam al-Din Hussaini, wrote the text in Peshawar. He classifies its rice in two varieties: “greater types […] used in the kitchens of nobles and sultans” and an unnamed host of lesser types.

Bara rice, he argues, is the apex. Hussaini comments on its “wonderful fragrance” and mentions that “when cooking, it lengthens and grows considerably.” British colonial reports written after their annexation of Peshawar in 1849 commented on the cultivation of this variety and its prevalence — albeit in small quantities — in eleven Pashtun villages.

According to Hussaini, Bara could be up to eight times as expensive as lesser strains. English-language sources from the early 19th century comment on the reputation and high price of Bara, exported “as a rarity” to Iran and Central Asia. In the 1820s and 30s, Peshawar was ruled by the Sikh king Ranjit Singh, who levied a tribute of Bara Rice on the province and used it as a gift in diplomatic exchanges. On its presence in Iran, the Polish poet and Iranologist Alexander Chodzko wrote in 1842: “the most exquisite rice is imported to Persia from […] Peshawur. Its grain is long and thin, and makes an excellent pillaw. […] a few handfuls, after being boiled, fill up a large saucepan.”

Rice from the subcontinent had been prized in Iran for a long time: the Mongol ruler Ghazan Khan (d. 1304) even tried and failed to propagate it in Iran during his reign. Furthermore, the rice traditions of the northern subcontinent shared a history with Iran, and valued similar traits in the grain. There were many types of rice, used historically in various ways, in South Asian and Iranian cooking. But in elite cuisine, the preparation of rice with cleanly separated grains, made from long-grained and fragrant species like Bara, was prized. That preference has now become more widespread, emerging as the quintessential style of rice cooking in Iran and also prominent in South Asia — most famously in biryani, a layered dish of spiced meat and rice.

Most people across the world today will turn to Basmati rice grown in northern India and Pakistan for this kind of cooking, as it has many of the same qualities of form and flavor. This Basmati boom reflects partly the considerable export of South Asian agricultural products to European markets established in the colonial era, but more immediately the 1960s and 70s ‘Green Revolution’ in which high-yield rices helped Indian and Pakistani Punjab go from “a net rice importer to […] a word leading rice […] producing region.”

An elite commodity: fits and starts in the Qajar era

While the references to Bara rice that I found in Iranian sources come from the late 19th century, they seem to reflect an established reputation. The Qajar prince Nadir Mirza writes in his Khwarakha-ye Irani (‘Iranian Foods’) that: “The best rice in terms of scent, delicateness, and refinement is Peshawar-i Hindustan, which is very tasty and light; pulao and chulao are cooked with it. In Iran rulers and the elite obtain it.”

But Nadir Mirza’s book also tells us there was no single consensus on its superiority. Adopting the voice of two generic characters, the ‘master of the house’ and the ‘housewife,’ he presents opposing views. The man of the house prefers a rice grown in Najaf (modern Iraq), “which is like Peshawar rice, and better than it.” The ‘housewife’ sticks her neck out for a shorter-grained, amber-scented variety from Mazandaran: “let me cast my own vote. The rice which they call anbarin […] is the best. It gives pulao and chulao the scent and flavor of its name.” Peshawar-i Hindustan was part of a varied rice landscape.

As a luxury item, Bara rice was also part of a limited circulation of elite exchanges of gifts and tribute, just as it had been in Ranjit Singh’s kingdom. Even though Singh’s government closely controlled the growing and selling of Bara, it did so not to expand cultivation and exports, but to secure the royal share. In 1837, an envoy from the court of Kabul to Iran made similar use of Bara rice along with other regional specialties: “During my travel,” he wrote, “I had presented one pair of Cashmeer shawls and […] fine Bara rice of Peshawar to Hájee, the minister, and to the Minister for Foreign Affairs two bundles of lamb skins of Bokhara and a quantity of Bara rice.”

Around 1857, Qajar prince Abbas Quli Mirza brought rice from Peshawar to his Mazandaran estate. He took advantage of Iran’s humid and rainy Caspian regional climate to propagate the strain locally. We do not know his motivations, but they were probably functional rather than due to any larger cultivation ambitions.

Abbas Quli put it to much the same use as earlier rulers and diplomats, either consuming it himself or sending it as a gift or tribute to the provincial governor stationed to the north in Sari, and to the Shah himself in Tehran. In 1860 Mirza Ibrahim, author of a Persian travelogue of northern Iran, wrote that the Bara rice — for all its quality — was too low-yield to be of use to the local peasantry.

Rebirth as Sadri and the economy of intensive growing

While it was gaining this initial foothold in Iran, Bara rice’s star faded on its home turf after the British annexed Peshawar in 1849. It continued to be grown, and valued: the ruler of Afghanistan Abd al-Rahman Khan (d. 1901) even bought land in the Bara-growing area “to secure a supply” according to the 1897-8 Gazetteer of the Peshawar District. But there were new competitors and tastes on the global market, including the Carolina Gold, grown in great quantities using enslaved labor in the Southern United States. In 1850, an article of the Edinburgh Journal, vol. 13 claimed that:

It may be doubted whether in flavour it [Peshawar Rice] is superior to the Carolina rice now so well known in this country […] we have known wealthy Anglo-Indian families who used in preference the broken, dark-looking Bengal rice, so cheap and common in England.

While rice production and export in Punjab is sometimes associated only with the Green Revolution, there had been a market for it prior to British annexation in 1849. In the 1830s, Bara had been able to carve out a market pushing east into Punjab, keeping other strains away. But in the vast colonial world, the field of competition had widened, and the American use of enslaved labor — along with Britain’s forcible opening of India’s economy — created price disparities that undermined local crops.

More research will have to be done to understand how Bara fit into this new, global competition between different grains. Probably of more immediate consequence to such a limited-quantity crop was that the new British government took no active interest in its growth, unlike the Sikh Empire that previously ruled the region. The prestige it had enjoyed among regional elites did not carry over. Seeds were being mixed, and most of what was grown was now being consumed in Peshawar. Some small efforts were taken to plant it elsewhere in India, but they failed. By 1868, the area of its cultivation had dropped more than fourfold.

As the century progressed in Iran, meanwhile, Bara rice appeared to gain more reach. An 1891 book, the Geography of Isfahan by Mirza Hussain Khan Tahvildar, listed Peshawar-e Hindustan as one variety of rice grown in the Isfahan area, which was one of the main rice-growing territories outside the Caspian coast, Iran’s ‘rice-basket.’ In the Special-catalog der Ausstellung des Persischen Reiches (‘Special Catalogue of the Exhibition of the Persian Empire’), and 1873 report on Iran’s commerce and produce published in Austria in conjunction with the Vienna World Fair, it is stated that this same rice, called “first in quality in Asia,” was being exported to Tehran from Khorasan in the northeast. But the numbers were still small: four horse-loads (presumably a year) compared to nineteen of Khorasani rice.

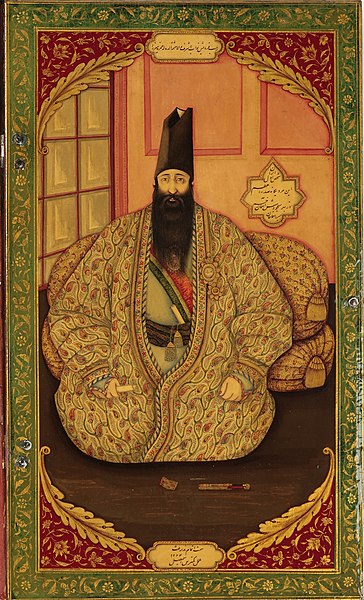

It was the Iranian Prime Minister Mirza Aqa Khan Nuri (d. 1865) who gave new impetus to Bara rice in Iran. Nuri imported and propagated Peshawar seed in his home province of Mazandaran, in the Caspian littoral, probably during his time in office between 1851 and 1858. Called Sadri after Nuri’s ministerial title — “sadr-e azam” meaning “prime minister” in Persian — it had dark reddish husks and long, thin grains just like Bara. Some variants ended up with yellowish husks as the strain took on its own life, but the core traits of flavor, size, and odor remained. Like the Bara, it was well suited to fine Iranian rice dishes.

In a comprehensive work on the Qajar state, the prince Muhammad Hassan Khan extolled Sadri’s delicacy and taste, and its popularity among different classes. Unlike its Bara parent, Sadri was widely grown:

Now, in the whole region of Mazandaran and the districts of Gilan, they plant this same seed: no other rice in Iran matches the abundance of Sadri […] which the inhabitants of Iran eat up to and beyond the limits of satiety. That which is obtained and is unneeded is exported to various lands.

In British India, Bara rice was suffering from Peshawar’s new place in a colonial economy and state whose rulers took little interest in its qualities. In Iran, its offshoot was thriving immensely. But this mass production was tied to similar pressures. In 1813 and 1828 Iran found itself defeated in war by Russia, which not only annexed territory but extracted trade privileges for itself. Russia eventually became Iran’s primary European trade partner.

As Shireen Mahdavi argues, “The Russians’ objective was to eliminate competition and influence the political system of the country through control of the market.” Rice grown in the Caspian littoral provinces, which abounded with Sadri, was a major portion of Iran’s new export regime with Russia. As Mohammad Ali Kazembeyki further clarifies, “the demand of the market in Russia and other foreign countries […] brought about commercialization of agriculture in Iran [and] Mazandaran.”

In the late 1880s an American observer noted that the small, oval-grained, amber-scented Anbarin rice of Mazandaran so valiantly defended by Nadir Mirza’s ‘housewife’ character “now rarely appears in the market, the Sadre [Sadri] having almost completely taken its place.”

The impetus towards large-scale expansion of Sadri grown for export was having an effect on the domestic market too. The common result of colonial pressures in British India and Iran was the loss of established grains with their own flavor and character, whether by the disappearance of the original Bara of Peshawar or the glut of Sadri, its Iranian descendant, that replaced local grains.

The view from the present

Bara rice from Peshawar is altogether gone in our time, dealt a mortal blow under British rule. Whatever was left of rice-growing in that area, according to Pakistan’s Express Tribune, finally ended in the 1980s when the Bara River was diverted. The rice landscape has narrowed further since the 19th century. Successful Iranian innovation along with Russian colonial pressure shaped its descendent Sadri, which still has a strong presence in the rice landscape of Iran.

But in today’s world economy, Basmati is the reigning king of long-grained rice and is most people’s first choice in South Asia for making pilau or biryani. Still, the culinary traditions in which Bara once claimed such a lofty position survive in those same dishes and their recipes, which continue to evoke the shared history of Iran, Central Asia, and the Subcontinent. Even with the Bara rice variety gone, its absence in the pilaus where it was once used continues to evoke these historical connections.

References

Burnes, Alexander. Travels into Bokhara, vol. 2. London: John Murray, 1834.

Chodzko, Alexander. Specimens of the Popular Poetry of Persia. London: Oriental Translation Fund, 1842.

Gazetteer of the Peshawar District, 1897-98. [Lahore]: Punjab Government.

Hussaini, Imam al-Din. Tarikh-i Hussain Shahi. Edited by Abd al-Khaliq Lalzad. London, 2018.

Ibrahim, Mirza. Safar-nama-yi Astarabad wa Mazandaran wa Gilan. Edited by Masud Gulzari. Tehran: Intisharat-i Buniyad-i Farhang-i Iran, [1975].

Khan, Muhammad Hassan ‘I‘timad al-saltanat.’ Chihil sal-i tarikh-i Iran […] al-Ma’asir wa al-Asar. Edited by Iraj Afshar. Tehran, 1362 [1983-4].

Kashee, Mahomed Hoosain. Account of an Embassy to the King of Persia from the Ameer of Kabul in 1837. In Selections from the Travels and Journals Preserved in the Bombay Secretariat. Edited by George Forrest. Bombay: Government Central Press, 1906.

Kazembeyki, Mohammad Ali. Society, Politics and Economics in Mazandaran, Iran 1848-1914. Routledge, 2003.

Mahdavi, Shireen. “Irano-Russian Trade and Travel: Haj Muhammad Hassan Amin al-Zarb and Others.” In Iranian Studies, Vol. 46, No. 2 (March 2013), pp. 207-226.

Mirza, Nadir. Khwarak-ha-yi Irani. Edited by Ahmad Mujtahid. Tehran: Danishgah-i Tihran, 2007.

Parizi, Mohammad Ebrahim Bastani. Paighambar-i duzdan, vol. 9. Tehran, Intisharat-i Amir-i Kabir: 1354 [1975-6].

Special-Catalog der Ausstellung des Persischen Reiches. Vienna: L.C. Zamarski, 1873.