The following is a guest post by Tyler Kynn, an Assistant Professor at Central Connecticut State University and creator of Seyahat, a free-to-play video game that allows players to travel the early modern Hajj route through the medieval Ottoman lands.

***

A female traveler enters a bustling coffeehouse outside of seventeenth-century Mostar in Bosnia. Seeing her high-status clothes, a man calls out to her; he says that he is a Venetian merchant and he needs her help to forge a hujjet (legal document) in the town’s Ottoman court to avoid paying the customs tax, a scheme he has plotted with a local Muslim trader. She rejects his offer and instead travels in the morning light over hills, through woods, and past farms until she arrives in Mostar. She goes straight to meet the judge in his hilltop home just past a scenic bridge. There, she tells him of the scheme she has heard. He nods his head, knowing fully well these two characters, and assures her that he will put a stop to their smuggling. She feels justice has been served and explores the town with its bathhouse, Ottoman mosque, running fountains, and caravansary before making her way on the road to her true destination: her hajj journey to Mecca.

This story is a recounting of the experiences of the main character in the educational video game Seyahat. The narrative was adapted from early modern Ottoman court records to help the player live the story rather than just read it.

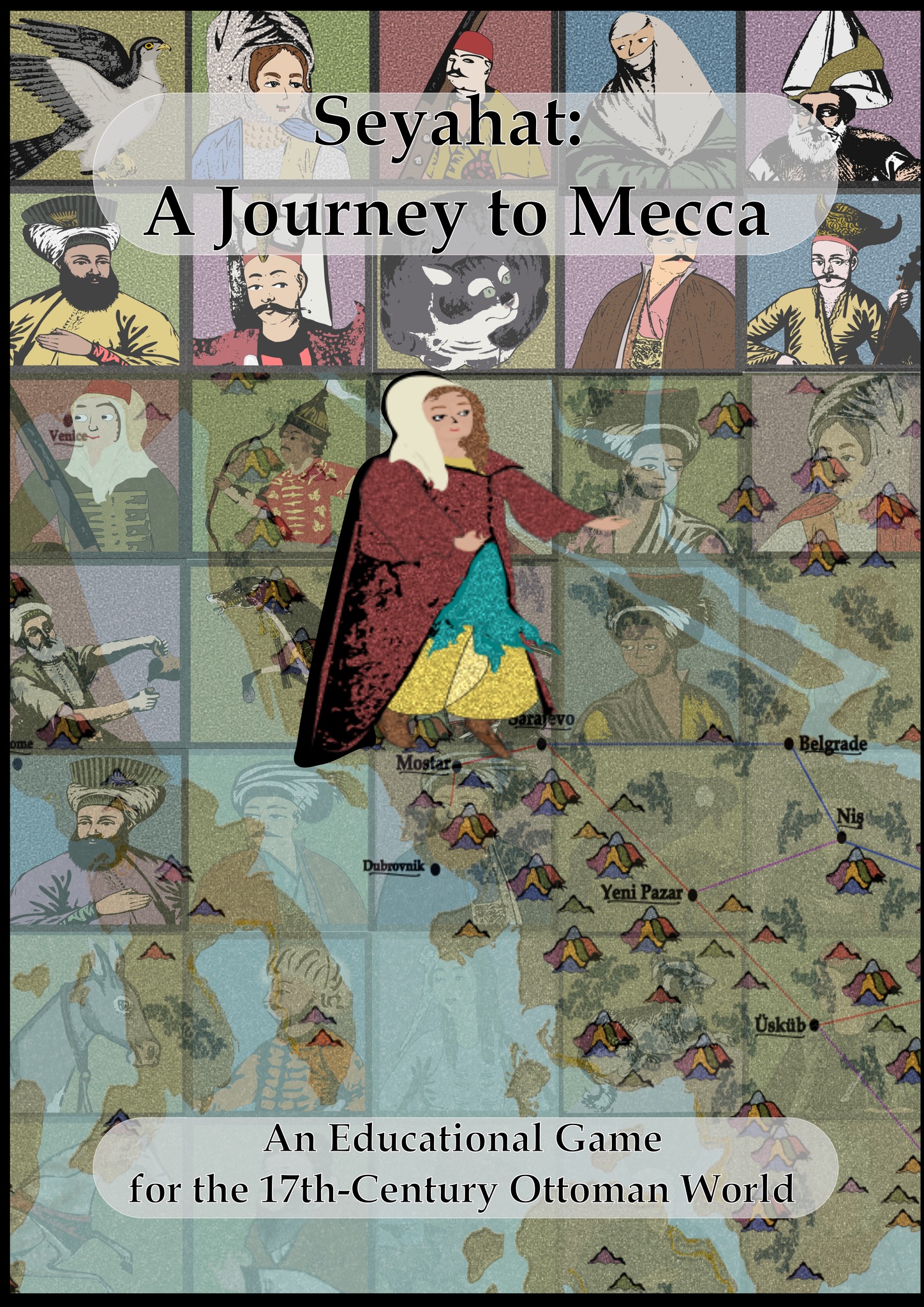

A video game based on primary source narratives can give players a glimpse into the experience of traveling across the early modern Ottoman world. Today, the journey to Mecca is done in a day on an airplane from anywhere in the world. The new educational video game Seyahat helps players and students encounter the stories of travel which so deeply defined the experience of the early modern journey from places like Bosnia to Mecca.

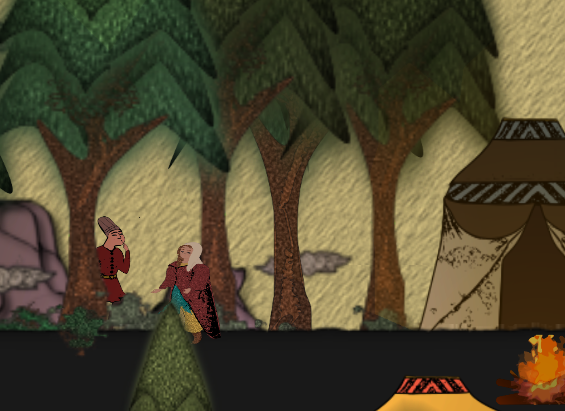

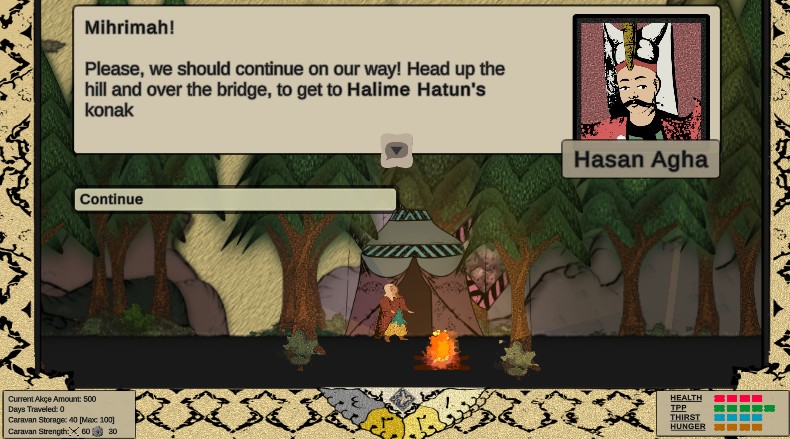

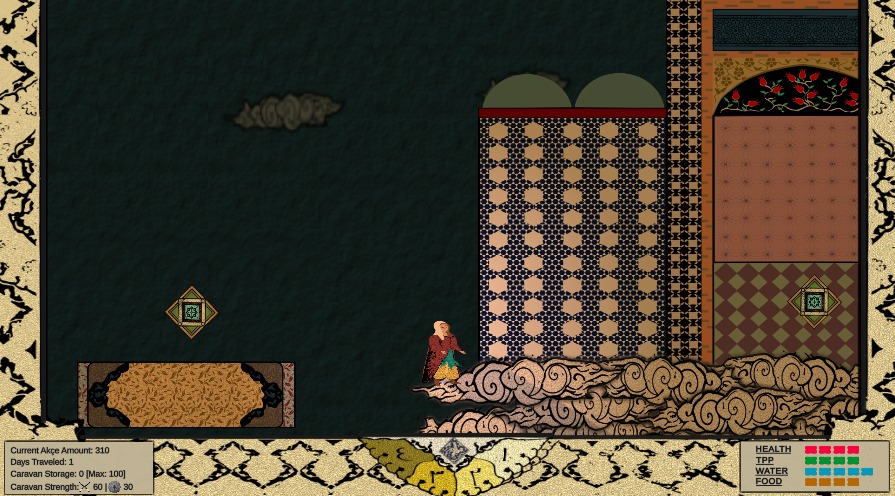

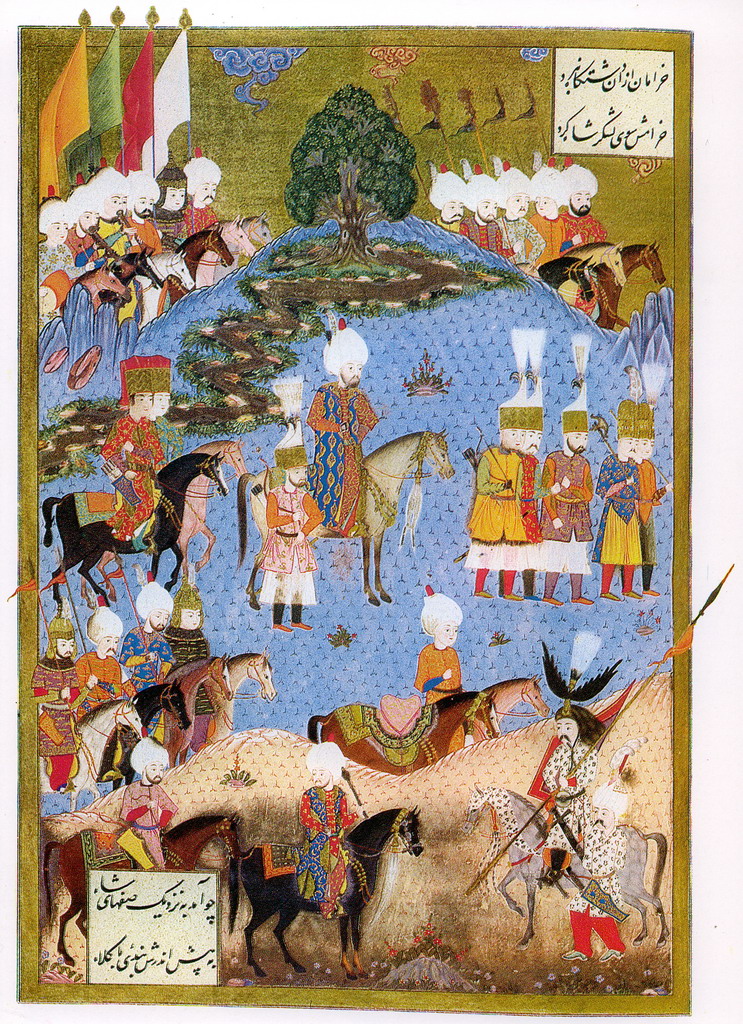

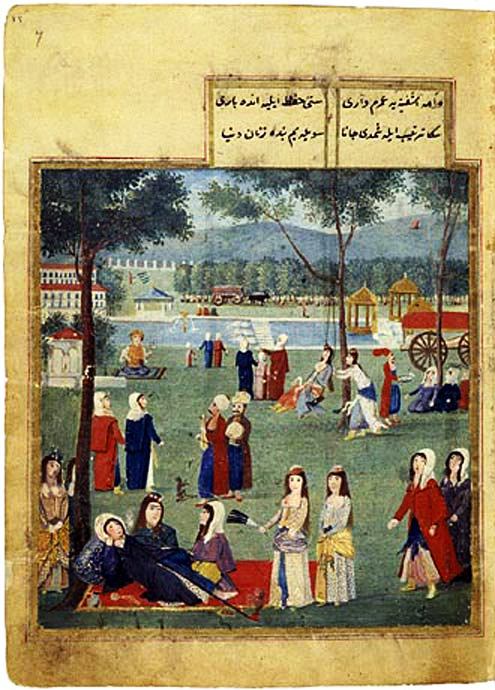

Over the past year, I have developed a free digital teaching tool to help the public better understand the cultural history of the early modern Ottoman world. This project takes the form of a side-scroller video game, allowing players to explore Ottoman social history through narratives inspired by Ottoman painting. The game, Seyahat: A Journey to Mecca (Seyahat being the Ottoman word for travel), newly released as a demo on the game platform Steam, presents the history of the early modern Ottoman world through this familiar medium.

Seyahat, developed with the Unity Game Engine, when fully completed will have the player follow the hajj route from seventeenth-century Ottoman Bosnia to Mecca exposing them to different peoples and historical narratives along the way. The demo currently allows you to travel through and around the town of Mostar in the tutorial section of the game.

Within this demo, players are introduced to a wide range of historical topics, including janissaries, the enderun, the Shahnameh, Ottoman court records, religious communities in the Ottoman world, and even early modern medicinal practices. These encounters are paired with historical context tabs for players who wish to know more about the term or topic presented. Seyahat is not intended to be the definitive learning experience for students of the Ottoman world, but rather to spark curiosity and provide players and students with a solid foundation for further learning.

Games are a powerful educational tool, and research shows that the element of choice in gameplay enhances active learning, helping students retain lessons more effectively. The interactivity of a game and the ways it engages the player make it a valuable tool in helping the public rethink their perspectives of the past and harmful stereotypes and orientalist tropes they may harbor.

A recent study focusing on whether video games can change player attitudes toward history provided evidence to demonstrate that “historical video games are capable of changing both short- and long-term explicit attitudes towards the historical events they depict.”

Seyahat will help players reshape their understanding of the early modern Ottoman past by focusing on travel and social history, rather than reinforcing the common portrayal of the Ottomans as merely a belligerent, militant, gunpowder-powered state often seen in other popular games.

The game relies on early modern Muslim travel narratives such as those of the seventeenth-century Ottoman traveler Evliya Çelebi who tells stories ranging from topics such as Bulgarian witches and cat salesmen to traveling dervishes and near-death experiences with bandits. Supplementing the travel narratives are stories published in early modern Ottoman court records and secondary literature that focus on social history.

When students enter an Islamic world history class on the first day, they often bring with them a range of preconceptions, stereotypes, and imaginaries about the Islamic world shaped by news, film, and, for many, video games. Video games are an important medium for scholars and educators to engage with because they already play a key role in shaping the public’s imagination of the past.

Rather than shy away from this, researchers and academics should work on developing their own games for education to both connect with students and counter prevailing depictions of the Islamic world in games more broadly. Many educators aim to dismantle preconceptions and demystify the past, and educational video games can be a valuable tool in achieving this goal.

Seyahat is developed as the spiritual sequel to my previous project – The Hajj Trail (www.hajjtrail.com) – a free text-based game developed by myself and Russ Gasdia. The Hajj Trail has been a successful educational tool, but I noticed that the text-based focus and static images of that game meant that some students would not engage with it as deeply.

Seyahat is designed to offer a more immersive experience, featuring a demo that I created in an Ottoman-inspired painting style, where players can navigate a movable character to explore the digital Ottoman world it portrays. The art design is largely based on Ottoman painting found in the following texts: the Süleymanname, various versions of the Shahnameh including Safavid versions, the Zennanname, and the works of the 18th-century court painter Abdulcelil Levni.

Immersion, gameplay loops, and player agency are the three core aspects that keep the player’s attention which in turn allows the player to learn the world the game is presenting. By building these new elements with Seyahat the hope is that the game will be more successful in pulling players into the stories the game aims to tell which are all based on primary source material chosen to present aspects of the social and cultural history of the Ottoman world.

The educational game Seyahat lets you explore the early modern Ottoman world and gives you a window into the social and cultural history of the Ottoman past. I invite you to play the recently-released demo and reach out via the discord linked on the game’s page for feedback.

Here is the link – happy travels: https://store.steampowered.com/app/3306180/Seyahat_A_Journey_to_Mecca/

Relevant References for this Post and Game Development

Evliya Çelebi, An Ottoman Traveller: Selections from the Book of Travels of Evliya Çelebi, trans. Robert Dankoff and Sooyong Kim, (London: Eland, 2010).

Kolek, Lukáš, Vít Šisler, Patrícia Martinková, Cyril Brom, “Can Video Games Change Attitudes Towards History? Results from a Laboratory Experiment Measuring Short- and Long-Term Effects,” in the Journal of Computer Assisted Learning 37 (5): 1348, 1364.

McCall, Jeremiah. “Why Play and Study Historical Games?,” in Gaming the Past: Using Video Games to Teach Secondary History, 2nd ed., (New York: Routledge, 2023), 6-21.

Payne, Matthew Thomas and Nina B. Huntemann, ed., How to Play Video Games, (New York: NYU Press, 2019).

Pierce, Leslie. Morality Tales: Law and Gender in the Ottoman Court of Aiutab, (Berkley, University of California Press, 2003).

Zimmermann, Felix. “Introduction: Approaching the Authenticities of Late Modernity,” in History in Games: Contingencies of an Authentic Past, Martin Lorber and Felix Zimmermann (eds.), (Bielefield: Transcript Verlag, 2020), 9-22.