The following is a guest post by Ava Hess, an Iranian-American curator and PhD Candidate in Art History at the University of California Los Angeles (UCLA). She is currently based in Tunisia where she is researching under-glass painting, printmaking, and figural Islamic art in the Maghrib for her dissertation.

***

At the center of the above drawing from a 15th-century Arabic manuscript stands a nude, bejeweled woman with long hair. She is larger than the other figures and holds one end of a chain wrapped around a man’s neck. Another male figure stands nearby with a drawn sword. The image accompanies text from a treatise on the occult properties of stones; it is a model of what to carve into a piece of onyx to make a planetary talisman. The resulting “planet-seal” is able to harness the power of Venus, attracting admiration and subservience to the stone’s carrier.

I first learned of this image in an essay by David Storm Rice, which is central to the questions raised by this article. I build upon new directions in Islamic historical scholarship on the intersections of art, astrology, enslavement, gender, and race by numerous scholars and draw on digitally available visual images from the collections of major libraries and arts institutions around the world.

The planet Venus is generally recognizable within Islamic art as a female musician, often playing a lute. This is the version of her you are likely to find in the galleries of the Met or the British Museum, in folios from illuminated manuscripts, luster-glaze ceramics, metalware, and other surviving works of royal or elite patronage. The consistency of the planet’s representation as a musician in courtly objects contrasts with the varied representations of her in talismans, objects imbued with magical power (talisman comes from the Arabic word talasm). In talismans, Venus is often a woman or goddess, but she can appear with bird feet, a mirror, or chains—although she is more often wearing rather than holding them.

On the surface, the two versions of Venus do not overlap as visual traditions: Venus as lute-player is dressed in fine garments and, as Rice points out, never appears in the nude. Likewise, the chain bearing or chain wearing Venuses are never playing a musical instrument. Venus in chains appears on everyday objects people used for magic or luck, traversing streets, shops, and people’s homes on seals, amulets, ceramics, bits of cloth or metal and other things, while Venus as a finely dressed musician lived a life of luxury on items marveled at in court.

What happens when these two versions of Venus are put into conversation? Why were planets represented as enslaved people in Islamic art? What do these images imply about medieval astrological understandings of the planets and their power?

In the case of the planet-seal described above, the talismanic visual image of slavery was intended to produce the effect of coercion in the real world, meaning to enchain the object of the magic spell into a love relationship. Anna Caiozzo examines planetary talismans, including the Venusian talisman from the first image, as important astrological-magical tools that derived their power from being used during specific astrological placements or through the replication of celestial iconography. They are just one of many types of talismans that scholars like Venetia Porter, Liana Seif, and Emilie Savagae-Smith have shown were produced and used across the medieval Islamic world, debates about their religious acceptance notwithstanding.

Instructions on how to make and use talismans appear in medieval treatises on the so-called “folk” or occult sciences. Their audiences included members of royal courts and also non-expert, educated classes and commercial or market-place astrologers. Sometimes these treatises include words, designs, or figurative iconography—including planetary imagery—that would be engraved, drawn, or otherwise applied to talismanic objects to activate their power.

Several scenes with a nude Venus in chains are found in the iconographic descriptions of the most famous Arabic-language text on astrological magic, the 10th or 11th-century Ghayat al-hakim, also known as the Picatrix. These images compel others to serve and please the talisman’s owner. For example, engraving lazulite with the same scene described in the onyx planet-seal above can procure the following outcomes: “He who carries the stone…will be liked by all, and people will feel attached to him and will gladly carry out all his wishes” and “Women feel attached to the bearer of the stone and are subservient to him.”

To achieve these outcomes, the scene’s three figures would have to be engraved into the stone during a Venusian hour and/or carried by the client when Venus is in the Ascendant, in one of its home signs (Taurus or Libra), and when its planetary hour is occurring. More descriptions of Venusian talismans showing similar scenes can be found in the studies conducted by Caiozzo as well as Henry Kahane, Renée Kahane and Angelina Pietrangeli, among others.

Venus (al-zuhara) as a lute player is one of several planets that appears in personified form and whose dress, props, and activities makes them immediately recognizable in artworks across mediums, especially manuscripts and other elite artistic productions of royal workshops.

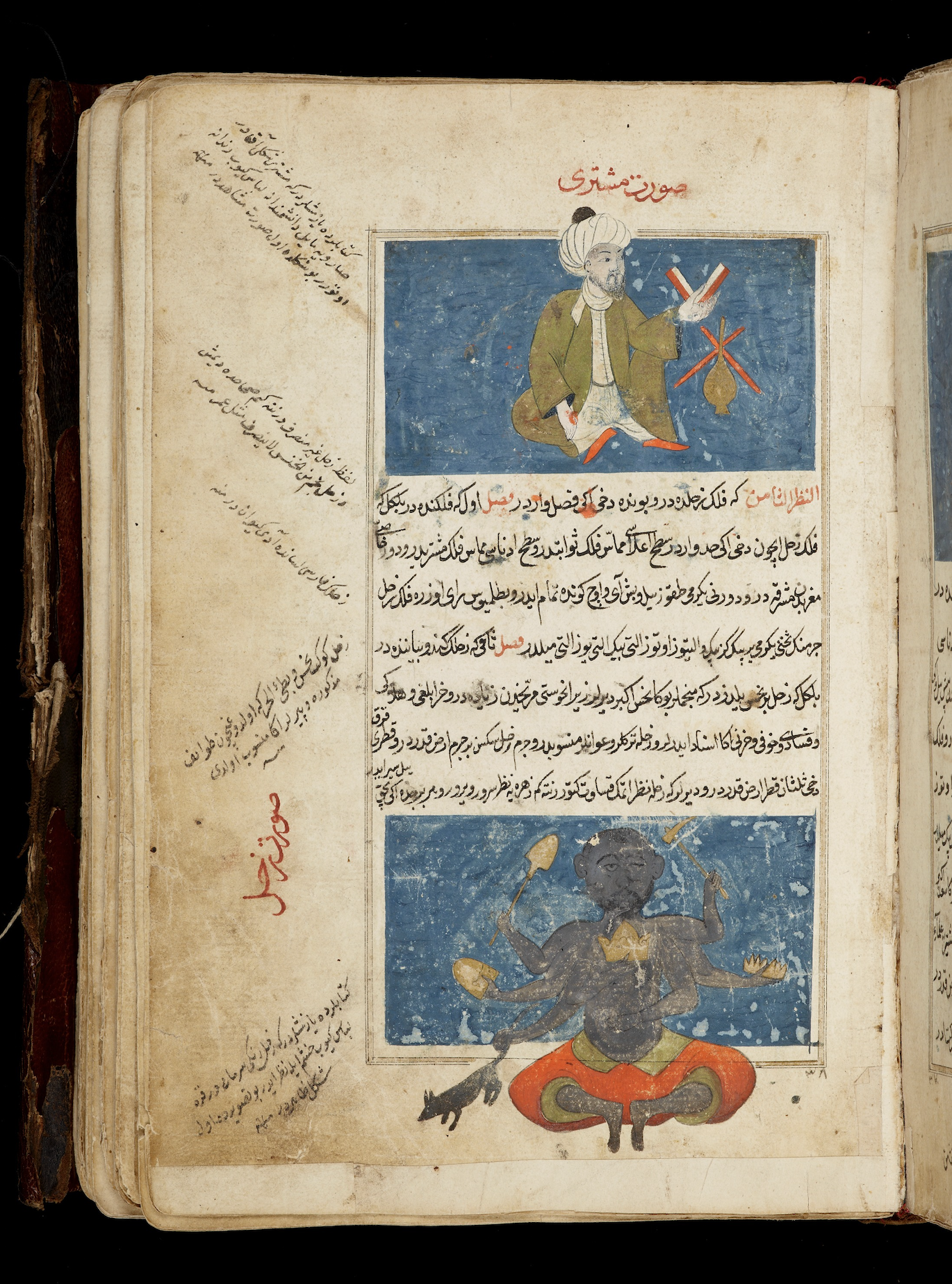

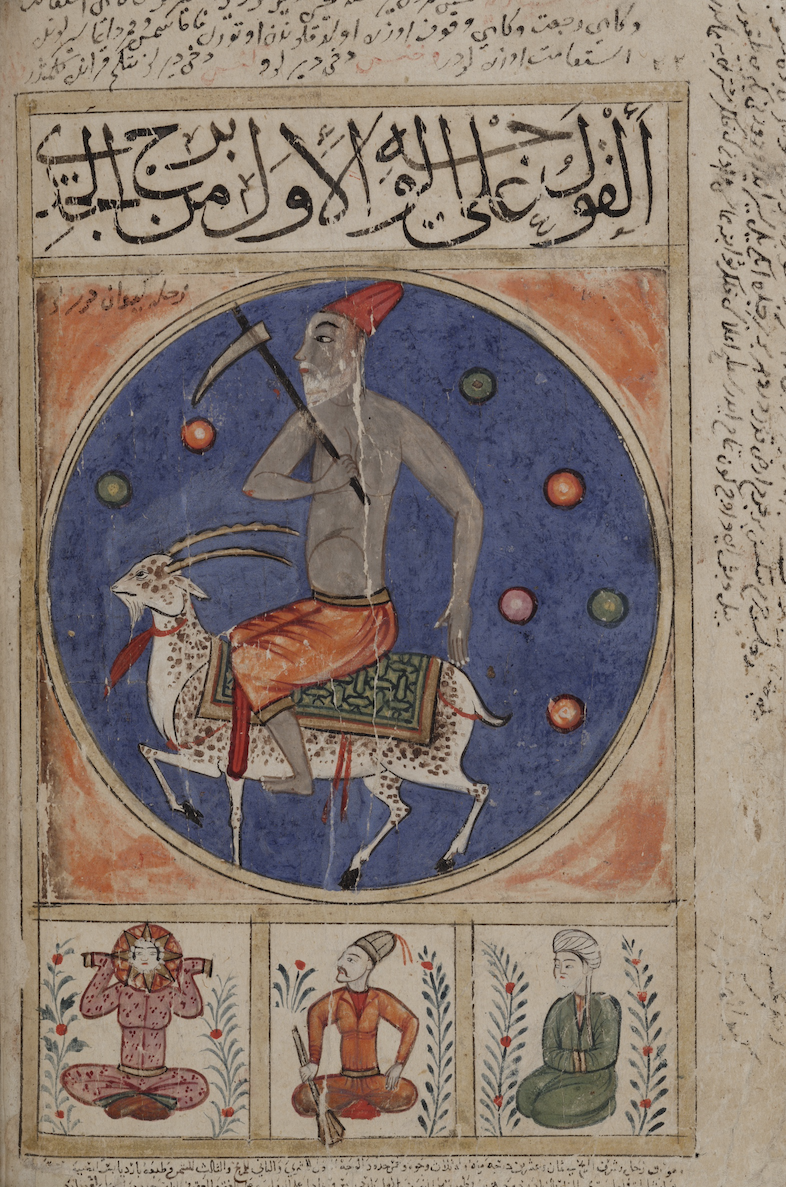

The other planets include: Mercury (‘utarid), shown reading or writing with a writing utensil or scroll to denote his role as a scribe; Mars (al-mirrikh) as a warrior or soldier holding a weapon and sometimes a severed head; Saturn (zuhal) as a dark-skinned man in a conical cap, often half-naked, with a sickle or pick-ax to imply his association with menial or agricultural labor; and Jupiter (al-mushtari) wearing a turban in reference to his position as a judge, man of law, or sage.

Numerous planetary figures can be seen in these folios from al-Qazwini’s “Aja’ib al-makhluqat wa- ghara’ib al-mawjudat (The wonders of creation and the oddities of existence)”:

Anthropomorphic representations of planets are not unique to Persianate or Islamic visual practice. But whereas in the Greek context they tend to appear godly, in the Islamic tradition they are more grounded in social roles including forms of forced labor or roles that could have been occupied by enslaved persons in the real world.

Medieval astronomers of the Islamic world understood there to be seven planets in total, including the sun, the moon, and the five planets visible to the naked eye. These were known in Arabic as “the wandering stars,” in contrast to the constellations or “the fixed stars”. Many of the greatest names in medieval Islamic astronomy were of Iranian origin (e.g. Abu Ma‘shar, al-Sufi, or al-Biruni) but their treatises were primarily written in Arabic, the lingua franca of their time for scientific or philosophical texts. Stefano Carboni explains that these historical figures translated, drew upon, and advanced Greek sources (most famously Ptolemy’s Almagest), the planets took on a more important role within Islamic astronomy and astrology. The need for visual representations of the planets grew as a result. However, while artists had mostly relied on Greek models for images of the Zodiac constellations, the planetary personifications had fewer iconographic precedents.

The visual system that developed for representing planets as human ‘types’ grew out of and contributed to associations between the planets and certain occupational activities. Astronomy and astrology were enmeshed and mutually reinforcing modes of knowledge production through which planets and stars were read in relation to one another to understand and make predictions about events on Earth. Scholars like Martina Müller-Wiener have demonstrated how these judgments relied on the associative nature of meaning-making within medieval Islamic cosmography whose “global system of correspondences” was amalgamated from multiple sources such as the classical Mediterranean, ancient Mesopotamia, pre-Islamic Iran, and South Asia. Every planet was surrounded by a body of knowledge, structured like a constellation, that mapped out connections between diverse places and epistemologies. Each was associated with a specific color and day of the week, weather conditions, personal temperaments, zodiac signs, regions of the world, objects, health conditions, as well as certain forms of labor.

In their literary and visual representations, the seven planetary personas often mirrored the structure of a typical Islamic court where each fulfilled a role, including those of an “unfree” nature. Scholars have increasingly turned to the term “unfree” to better encapsulate the complex and overlapping legal definitions and processes of identity formation in the medieval world; while the word “slave” from today’s vantage point is often understood as a fixed category, it was possible in the premodern Islamic world to move in and out of an “unfree” legal status over the course of an individual’s life.

Especially useful here is the category of “unfree elite” used by Islamic art historian Glaire Anderson to refer to members of Islamic court circles such as eunuchs, administrators, military leaders, concubines and court performers. These were highly educated and rigorously trained persons under conditions of forced labor who nevertheless accessed privilege and power based on their proximity to royalty, ability to amass wealth, and physical, intellectual, or creative talents.

On the one hand, it makes sense that planets were envisioned in the context of a governing structure like a royal court given their role as ruling bodies within Islamic cosmography. As Ali Olomi has explored, the planets govern the Zodiac signs, environmental and political events on Earth, even the stages of your life as an individual. On the other hand, these representations hint that the control of certain planets is not absolute, since they are in the contradictory position of holding elite privilege within unfree conditions.

Throughout the courtly arts, representations of Venus as a musical performer share much in common with descriptions of the qayna (pl. qiyan), a quintessential example of the “unfree elite” class. Qiyan were a subset of female domestic slaves (jawari) who served as dancers, singers, and/or musicians at Islamic courts from the Abbasid period on. They underwent multidisciplinary performing arts and intellectual training in areas like poetry, chess, or pharmacology. They were sometimes also intimate partners of rulers and the mothers of caliphs and sultans. Despite their diversity of skills, qiyan are predominantly represented as musicians, as in the Cappella Palatina paintings studied by Lev A. Kapitaikin. Venus’s consistent appearance as a lute player – even in imagery accompanying texts that make no mention of Venus as the planet that governs courtly entertainment – further associates her with the figure of the qayna.

Lamia Balafrej has recently shown how medieval Islamic diagrams of mechanical devices offer a rich archive of imagery related to female domestic slaves – specifically that of “instrumental jawari” and feminized, figurative proto-robotic forms – and should thus be regarded not as apolitical or neutral technical documents but as ones enmeshed in specific social relations and dynamics around labor, enslavement, servitude, and visibility. Drawing on such an approach, can similar questions be asked of imagery related to musicians, qiyan, even Venus?

In fact, Venus is not the only planetary persona whose depicted role implies an elite but “unfree” legal status. Another example is Mercury, since courtly scribes and performers were in various historical moments part of enslaved groups whose livelihood, as Elizabeth Urban argues depended on their linguistic prowess and mastery of the Arabic language. The frequent depiction of Mars as a soldier offers another possible example: while soldiers were not always unfree, armies of the enslaved were a widely known phenomenon, as in the case of the Mamluks (whose name literally translates to “enslaved”).

The physical attributes of planetary representations could also imply unfree status. Mercury the scribe often appears unbearded with a more youthful or androgynous look than other masculine planetary figures. Could these characteristics be a nod to literary references of the planet as a eunuch, thereby linking him with another category of unfree persons within a courtly context?

Scholars of Islamic cosmography have often singled Saturn out as an astrological “other” among his planetary peers. The planet’s geographic correspondence is with the first clime, including East Africa and South Asia, and its visual representations often took the appearance of a dark-skinned South Asian man. According to Olomi, Saturn would become increasingly racialized by early modern astrologers. This was especially true in the Turko-Persian world and Europe, where it was seen as governing Blackness as a racial category, in contrast to earlier astrologers who understood its associations as more amorphous and geographic.

Saturn iconography may have provided a visual prototype for representations of the “foreign” and even of labor that were entirely unrelated to astrology, as Müller-Weiner argues. She interprets how illustrations of the “elephant clock” designed by al-Jazari in 1206 as combining Saturn’s associations with India, the sickle or scythe, and time-keeping all in one image of an automated slave — the elephant driver automaton that operates the clock. Balafrej suggests it is crucial to recognize that this is an image of an “automated slave” — the elephant driver automaton that operates the clock.

Saturn’s dark skin is a visual marker of ethnic difference and, although enslaved persons were not always of darker complexion, they were mostly of different ethnic (and religious) origin than their masters. Even if skin color did not determine enslavement, its representation nevertheless shaped perceptions of slavery, divisions of labor, and asymmetrical power dynamics, As noted in Rice’s description of the drawing,frej has demonstrated. Ongoing research by Balafrej, Kristina Richardson, and others explores further connections between visual depictions of Saturn and slavery.

What types of hierarchies are suggested when planets are shown together? In our first talismanic example, the design for an onyx planet-seal shows a trio: the chain-bearing Venus, her shackled victim, and a sword-bearing onlooker. As noted in Rice’s description of the drawing, the chained male figure held by Venus is Kronos, the ruler of time linked with Saturn in both Roman and Islamic contexts. He wears a stock feature of Saturn imagery, the conical cap. These are two planets differentiated from the others in highly visible ways—on the basis of gender and phenotype. Here, they exhibit a dynamic of coercion.

When holding Saturn’s chains, Venus appears in control. But just behind her lingers the threat of the sword-bearing figure. This same figure, likely linked to Mars, holds Venus’s chains in talismanic scenes where she is the one shackled. Does the repeated inclusion of Mars the soldier in these scenes allude to the role of war in the history of slavery or to the use of violent force inherent in enslavement?

The arts did not just represent a pre-existing body of knowledge. They played an active role in creating astrological meaning. Talismanic objects were ubiquitous and mobile across social registers. Their visual representations shaped how people of different classes conceptualized astrology. Their use of nudity—a rarity in medieval Islamic figural traditions—could have, for example, reinforced an association between Venus and unfree women at court such as concubines, courtesans, and even courtly performers like qiyan, who were sometimes depicted wearing translucent robes.

A singular and mysterious drawing from Fatimid Egypt helps show how the boundaries between elite and non-elite culture were often quite porous, hinting at a possible meeting of the two Venuses. It is believed to have come from 11th-century Fustat in modern-day Cairo and pictures a nude, tattooed, and long-locked female figure holding a cup in one hand and a stringed instrument in the other. Rice draws a connection between the Fatimid drawing and the 15th-century talismanic image this article began with, pointing out obvious parallels between the two. But, as Jonathan Bloom notes, scholarly interpretations have alternated between seeing the Fatimid figure either as a courtesan/lute-player or a generic representation of Venus. Could it not be both?

Representations of Venus in Islamic art as an “unfree elite” figure both preserve pre-Islamic associations of the planets while also situating them within the socio-historical contexts of Islamic courts and the (forced) labor they relied on.

So what are the implications of representing cosmic entities as unfree human figures? If the movements of stars and planets are said to have power and influence over human activity, then perhaps these human-made images signify a latent desire to curb or even control that power. We find generic images of coercion on talismans, which are themselves meant to bend the will of love in one’s personal life. In works of more privileged patronage, we see courtly hierarchies from real life recreated as a court made up of the planetary figures.

Historically, the unfree elite classes of Islamic courts were subjected to forced labor but were also known to wield power, influence, and agency in their own ways. Neither the unfree elite nor the planets and stars are completely controllable, but are instead caught in a delicate dance between exploitation and privilege.

For invaluable comments and feedback, I would like to thank Dr. Lamia Balafrej, whose graduate seminar on minorities in Islamic art served as the original impetus for a longer version of this paper, as well as the respondents at conferences held at UCLA and UCI where it was subsequently presented.