The following is a guest post by Veera Rustomji, a multidisciplinary artist and researcher from Karachi, Pakistan. She is the co-director of the Urban Repository Archive (URA) and faculty at the Indus Valley School of Art and Architecture. Her work can be viewed at www.veerarustomji.com.

All photographs taken by the author, unless otherwise noted.

***

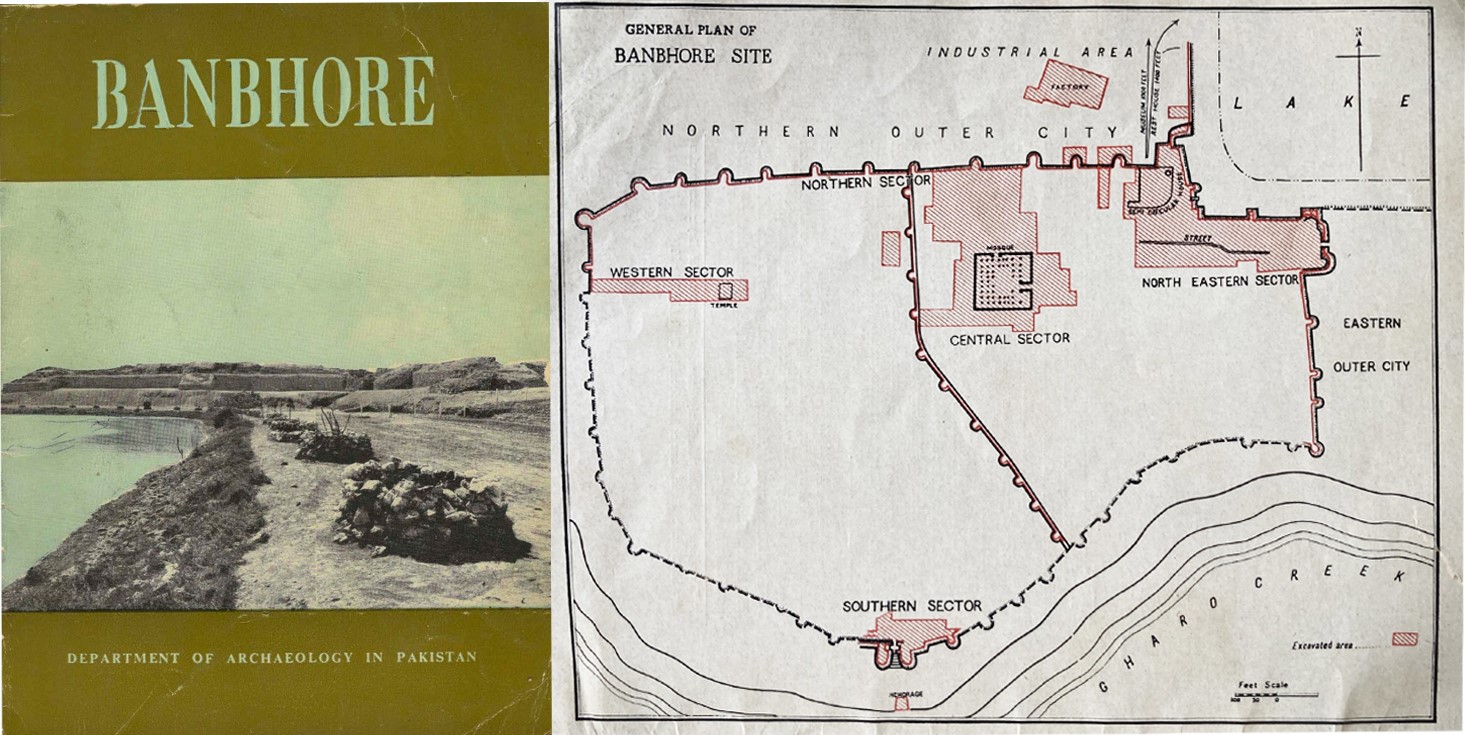

Just an hour and a half drive from Karachi lies an archaeological site called Banbhore, which I first visited in 2021 to conduct a survey with a maritime archaeology company. Once we veered off the highway towards the wind-channels of the Indus Delta, I could smell the salty sea approaching.

At the ticket counter, visitors get an immediate vantage point of Banbhore’s stone rampart. Walking past vestiges of the artisans’ quarter, a large cement stairway leads up to the fortified wall, cutting across the bastions and into the elevated citadel. Wooden signboards indicate the remnants of a Hindu temple, the ‘Grand Mosque’, a ‘palatial’ house, and residences.

Hearing my footsteps crunch over burnished yellow sand, I looked down to see specks of terracotta pottery mixed with ivory off-cuts. This pathway meanders through the centre of the site, extending downhill to the beach, and opening to frame an inlet of the Arabian Sea meeting Gharo Creek. The sea breeze is the soundtrack to which a speckling of wind turbines attune across the water.

Archaeologists have linked Banbhore with the ancient harbour town of Daybul, dating back to the Indo-Parthian period of the first century BCE, which was later conquered by the Umayyad general Muhammad ibn Qasim in 712 CE. For centuries, historians depicted Daybul as a frontier between the Islamic and Indic worlds.

The first excavations at Banbhore ran from 1958 to 1965 under Dr. Fazal Ahmed Khan, who was later appointed as the Director of Archaeology and Museums of Pakistan. In preparation for my first visit, I had studied Khan’s report, which examined the stratigraphy of Banbhore as a hub for mercantile relations spanning from the Persian Gulf to South East Asia.

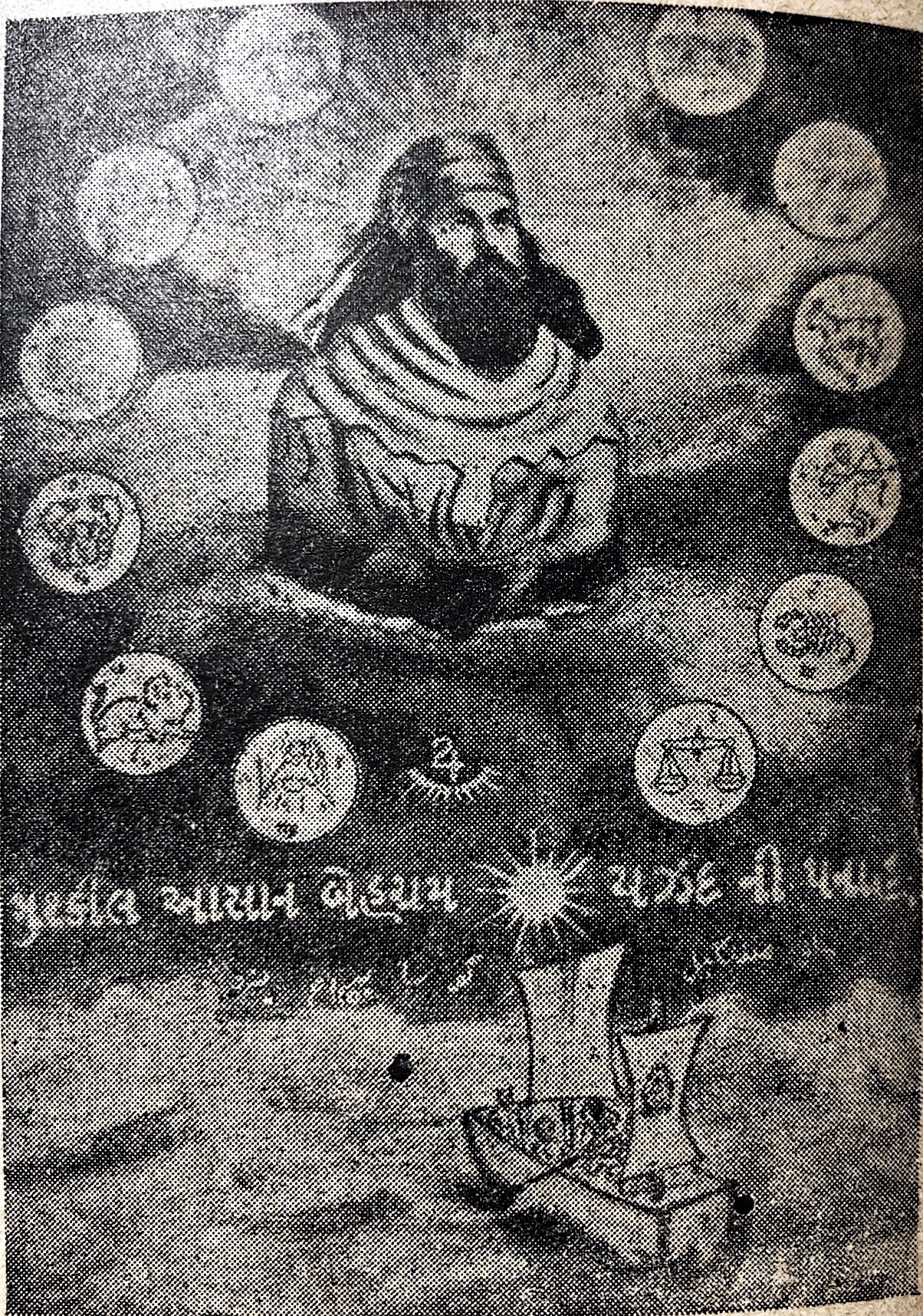

Amidst a long list of excavated items, the objects I found most intriguing were three Sasanian-era coins, which Khan categorized as ‘Indo-Sasanian’ and ‘Arab Sasanian.’ He describes them as evidence of Sindh being a satrapy of the Sasanians, the last Iranian Zoroastrian dynasty. Further investigation through Pakistan Archaeology Journals led me to find original and replica silver drachma Sasanian coins within the collections of two public museums in Karachi: the National Museum of Pakistan and the State Bank Museum. The obverse of the coins depict profiles of the Sasanian kings; their aquiline noses accompanied by bespoke diadems sitting upon a head of curls are quintessential features of Persian monarchs in full regalia. The reverse of the coins features the image of the sacred Zoroastrian fire (atash) burning from the large vase (afringanyu) with attendees on either side, encircled with a Pahlavi inscription. This is a hallmark image widely visible across fire temples, Zoroastrian cultural institutes, and homes.

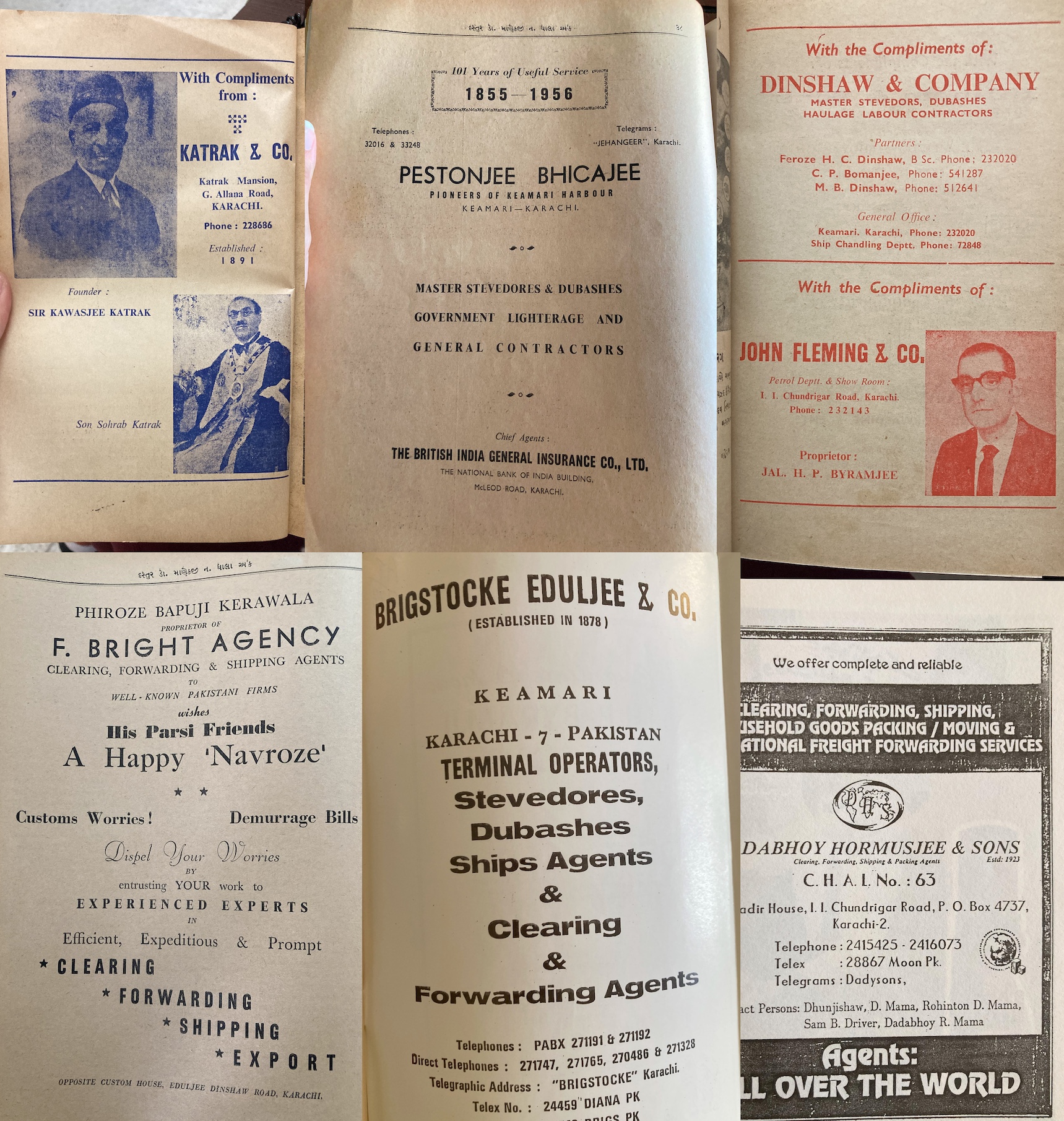

I never anticipated that the Zoroastrian community to which I belong would have ties to archaeological evidence such as these coins, attesting to the religion’s presence within the wider landscape of Sindh. Today, Pakistan’s Zoroastrian population numbers less than 1000 individuals and is predominantly based in Karachi. They trace their arrival to the city with the influx of entrepreneurship and opportunities available after the British developed Karachi into a deep-water port in the 1870s.

However, these coins, dating from 441–652 CE, suggest that traders from the Sasanian-Zoroastrian domain established commercial relations with Sindh long before British colonial rule. This evidence should prompt a reevaluation of the timelines associated with merchants of Zoroastrian heritage and the religion’s physical presence along the Sindh coast, especially with regard to maritime history.

Karachi’s Zoroastrian community draws its visual vocabulary and cultural ancestry from Gujarat, India, and not from Iran, the stronghold of ancient Zoroastrian imperialism. This is because the Zoroastrians in Pakistan are predominantly Parsi, having trickled into the Indian subcontinent via both maritime and terrestrial routes after Sasanian rule in Iran.

A narrative of this migration was authored in 1599 by Bahman Keikobad, a high priest of Sanjan, and titled the epoch as the Qissa-e-Sanjan. The qissa is really a poem in the Persian bahr-e-hazaj meter. The first half chronicles how Iran’s Zoroastrians sought refuge after the fall of Yazdegird III, making a sea voyage from the port of Hormuz to the island of Diu and finally, Gujarat.

The second half of the poem is dedicated to eulogizing how the Zoroastrians integrated into the social and cultural fabric of Gujarat and cemented their new homeland with the creation of the IranShah, the oldest atash burning in South Asia, which is preserved in the town of Udvada.

As a child growing up in Karachi’s Zoroastrian community in the early 2000s, I attended ‘Sunday school’ classes where prayers and religious literature were read aloud and translated to us. It was during those classes that I first learned about the Qissa-e-Sanjan.

The image of the stormy seas and the shipwrecked Zoroastrians cascading onto the coasts of Gujarat stayed with me. My second dose of education in Zoroastrian history presented itself 15 years later when I was an art student in a programme called the Zoroastrian Return to Roots (RTR), an initiative to connect the religion’s youth across the diaspora by visiting places, businesses, and individuals of Zoroastrian significance in India. Part of RTR’s itinerary follows the route of the sacred IranShah atash which was transported across the Valsad district of Gujarat, as narrated in the Qissa.

We were taken to Sanjan and drove further west to a sandy fishing village on Nargol beach where rows of boomla (Bombay duck) are caught and dried. Archaeologist Dr. Rukshana Nanji guided us through the site. According to Nanji, the proximity of Nargol to Sanjan suggested the beach as a possible landing spot for Zoroastrians coming from Iran.

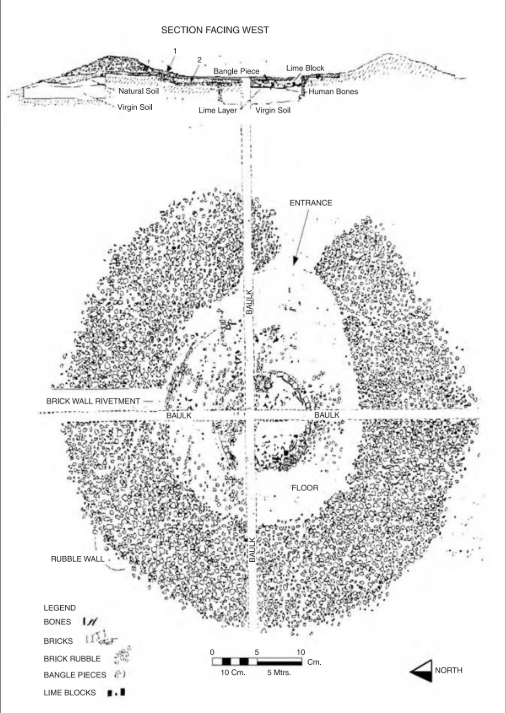

As we trekked inland to another village, Nanji gathered us around a grassy mound which had been excavated in 2002. She pointed out that although the Qissa-e-Sanjan has become a crux upon which most Parsis explain and reassert their Gujarati heritage, no one had attempted to archaeologically verify or refute the poem. Once the World Zarathustri Cultural Foundation commissioned this expedition, remote sensing methods were employed, maps studied and trenches laid out.

Not only did these excavations find a vibrant port city underneath the Sanjan village, they also uncovered the remains of an ancient dokhma, known more commonly as a Tower of Silence, a structure used in Zoroastrian funerary rites.

This unassuming mound which RTR participants visit every year at Sanjan, is the location of this dokhma. Multiple specimens of bones and material debris attested to occupational alignments which fit perfectly within the scope of the Qissa-e-Sanjan. While the intention of the Qissa was never concerned with prescribing factual details, it was the results from the Sanjan excavations which proved the existence of a culture akin to how the Zoroastrians narrated in the Qissa would have lived between the 10th-11th centuries.

Nanji’s guided tour on the shores of Gujarat and unveiling of archaeological findings was transformative in my understanding of material culture associated with the first waves of Zoroastrians in South Asia. Returning to Karachi, I finished art school while writing about how archaeologists from the 2002 excavations found physical lineages coinciding with an intangible story passed down for generations.

***

In December 2023, I found myself once again part of the RTR programme, but this time as a volunteer, bringing 30 Zoroastrians across the globe for a two-week tour. The programme included Dr. Kurush Dalal, the Field Director for the 2002 Sanjan excavations. Dalal corroborated many points about the Qissa-e-Sanjan which I had learned from Nanji back in 2015. But Dalal’s orientation expanded upon how the influences of geography, climate, flora, and fauna shaped the rituals and customs of the Zoroastrians who migrated to India. He outlined how Sanjan could be where Zoroastrians began to acquire their local Parsi identity by inculcating Gujarati food, language, and dress into their customs. As Dalal showed us diagrams of the excavations at Sanjan, F.A. Khan’s report on Banbhore was on my mind.

Due to geomorphological changes, Nargol, Sanjan, and Banbhore have all long since forsaken their maritime importance for seafaring merchants such as the Iranian Zoroastrians who traded spices, raw materials, and crafts. This made me think about how interwoven the physical changes of anchorages across Gujarat and Sindh coastlines are with the studies of shifting Zoroastrian settlements.

Dalal explained that spices such as turmeric, pepper, ginger, cardamon, cassia leaves, and onions were staple imports from India to Iran. Historians and geographers have recorded how Persians developed methods of harnessing the directions of wind to monopolise prosperous maritime trade in the Arabian Sea, reaching a peak with the Sasanian navy. Dalal argued that the Zoroastrians detailed in the Qissa-e-Sanjan around the 10th century were well aware of the voyages by their Sasanian predecessors towards India and were able to navigate to Gujarat after the demise of the Sasanians.

And as for Daybul? It certainly didn’t provide a homeland for the faith, but it was these very characteristics of the nautically-minded Zoroastrians which brought them in contact with Sindh, importing musk, castor, and herbs while exporting pearls and luxurious Persian crafts.

In fact, one of the coins at the State Bank Museum in Karachi is from the reign of Anushirvan Khosrow I (531–579 CE), under whose reign attempts to dominate the maritime Silk Route reached an all-time high. However, evidence of Zoroastrians in Sindh neither begins nor ends with Sasanian coins. At Banbhore Museum, antiquities such as turquoise monochrome urns and torpedo-shaped jars imported from the Persian Gulf and vessels decorated with relief-moulded designs are local adaptations of distinctive Iranian craftsmanship. Field Director and pottery specialist of the Banbhore excavations, Dr Agnese Fusaro, explained to me when I was in Banbhore that these artifacts reflect the affluence of Daybul as well as the advantages of being part of a network of Indian Ocean commerce.

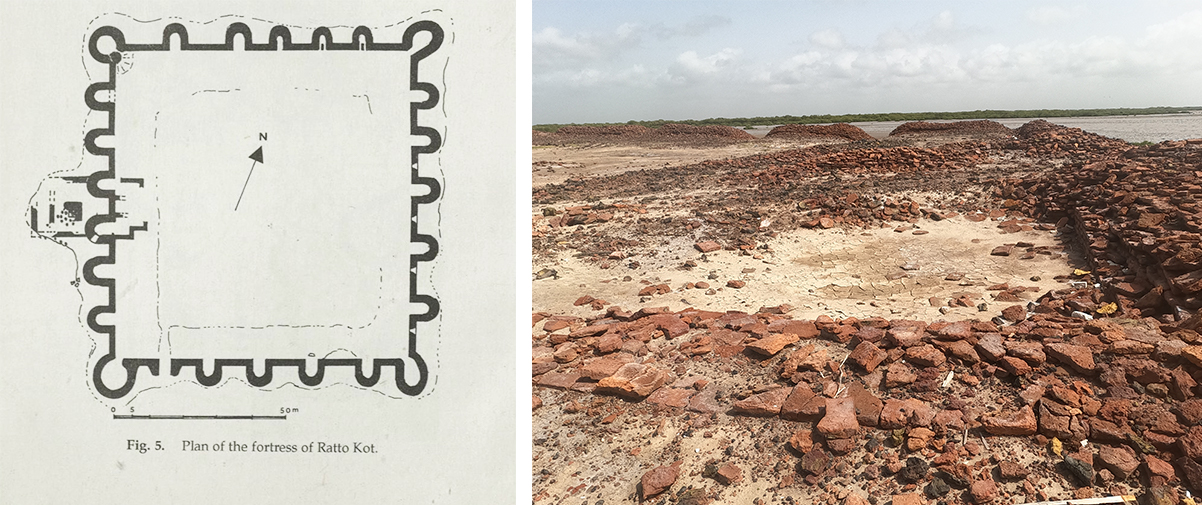

Beyond artifacts, the construction strategies deployed by the Sasanians in the Indus Delta also deserve attention. French archaeologist Monique Kevran published extensive research (referenced in the bibliography below) in the 1990s about ancient fortifications around the delta such as Ratto Kot, postulating it to have foundational origins with Sasanian King Bahram Gur V (420–438 CE) who historians say took a Sindhi princess as his wife and received Daybul along with the littoral regions of Sindh and Makran as dowry.

Kervan furthers these cross-cultural studies to show Ratto Kot’s layout to share a ‘barbicane’ defense structure similar to fortresses in ancient Iran designed for combat. Having visited Ratto Kot amidst the dense mangrove forests of the Indus Delta, I came away noticing nothing visibly ‘Zoroastrian’ or ‘Sasanian’ from the dilapidated red brick structure. And, after many visits to the Banbhore Museum, I have also realized it requires extensive reading to be able to dissect the multiethnic nature of objects on display.

What is then the significance of these archaeological findings to contemporary Zoroastrians in Pakistan and the diaspora? Relics like coins, ceramics, and fortress walls offer little resonance unless they are well-known and frequently engaged with via curated efforts or, through academic research in accessible formats that include communities.

But most scholars who write about Zoroastrian migration waves from Iran to Gujarat seldom factor the approximately 1000 km long coastline of Pakistan connecting these two bases. As a result, Daybul’s significance is ignored in scholarship about Zoroastrian trading relations and the historical chronicling of voyages and migration which the Qissa mandates.

Culturally, Karachi’s Parsis are an offshoot from Gujarat. But there are possibilities for the community to build a more nuanced appreciation for how coastlines, harbours, and trade played vital roles in their blueprint. Rather than viewing themselves as isolated from their urban surroundings, these findings should help bridge the gap between the community and Karachi’s peripheral areas. But this continues to present challenges because of the way Parsi identity has been largely shaped by the historical narrative of the Qissa-e-Sanjan, which privileges the Gujarati origin story.

The larger question remains: are we letting the Qissa overshadow material culture, thereby sidelining alternative sources of knowledge and evidence that could potentially integrate sites such as Banbhore into the stories of Zoroastrianism’s reach across South Asia?

Looking to find some answers, I spent a week in Banbhore in December 2024, researching excavated materials alongside specialists of the Joint-Italian-Pakistani Historical-Archaeological Expedition mission, currently excavating the site. Holding artifacts of clay, ivory, metal, and glass in my palms, feeling their crevices, brittleness, and weight, I noted their varying chemical compositions and utilitarian purposes. Each object had its own story to tell. And yet there is still much to uncover about Daybul’s occupants and their multi-ethnic lineages.

At the end of each work day at Banbhore, I would walk past the citadel to the shoreline. I thought about how inherited stories of migration and survival may not always exist in the form of textures, smells, and colors of the artifacts I was studying, but they are still sensorial and can live at the forefront of a community’s consciousness, reminding them of where they came from. However the one pervading visual which the community has retained through centuries is that of a sea-borne journey via the Arabian Sea whose waters reach the shores of Sindh and Gujarat.

Perhaps the materiality of Zoroastrian heritage will always be in ’competition’ with the oral tradition. But there is still time to position Sindh as central to the inheritance of the Karachi Parsi community’s history.

***

This research was facilitated by the joint Italian-Pakistani Historical-Archaeological Expedition, The Department of Culture, Tourism Antiquities & Archives of Sindh and the Zoroastrian Return to Roots programme.

References

Lionel Casson (Ed. and Trans.), The Periplus Maris Erythraei, Princeton University Press, 1989.

William Dalrymple, The Golden Road: How Ancient India Transformed the World, Bloomsbury Publishing, 2024.

A. C. Felici et. all Banbhore, A Major Trade Centre on the Indus’ Delta: Notes on the Pakistani-Italian Excavations and Research, Proceedings of the 10th International Congress on the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East, April 2016, Vienna.

Valeria Piacentini Fiorani & Agnese Fusaro, Eleventh–Twelfth Century: Political and Economic Balances in the Western Indian Ocean in the Light of Historical and Ceramic Evidence from the Site of Banbhore/Daybul, Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies, 51 (2022).

Hadi Hasan, A History of Persian Navigation, 1928, p. 65. References Al Ṭabarī’s Tārīkh al-Rusul wa al-Mulūk (History of the Prophets and the Kings, also referred to as Tarikh-i-Al Tabari).

John R. Hinnels and Alan Williams (Eds.), Parsis in India and the Diaspora, Routledge, 2008.

Mani Kamerkar and Soonu Dhunjisha, From the Iranian Plateau to the Shores of Gujarat: The Story of Parsi Settlements and Absorption in India, K.R. Cama Oriental Institute, 2002.

Monique Kervran, The Fortress of Ratto Kot at the Mouth of the Banbhore River (Indus Delta, Sindh, Pakistan), Pakistan Archaeology, Vol. 27, 1992.

Dr. F. A. Khan, Banbhore: A Preliminary Report on the Recent Archaeological Excavations at Banbhore, Department of Archaeology and Museums, Government of Pakistan, 1970.

Firoza Punthakey Mistree and Feroza Godrej (Eds.), A Zoroastrian Tapestry, 2002.

Sindh Antiquities Biannual Journal – Special Edition on Banbhore Excavations, 2019.

Andre Wink, Al-Hind: The Making of the Indo-Islamic World: Early Medieval India and the Expansion of Islam 7th-11th Centuries, Brill, 2002.

Zoroastrian Return to Roots: https://zororoots.org/