When Israel launched a surprise attack on Iran in June 2025, protests broke out around the world.

Different versions of the Iranian flag appeared at rallies; at “No War on Iran” marches, many waved the official flag with the “Allah” emblem. Others waved red-white-and-green flags with an empty center, and others held aloft a tricolor with a Kufi emblem reading “Woman Life Freedom” in Persian. At some protests, and even counter-rallies in support of Israel, another version appeared: the Lion and Sun Flag.

Flags represent identity and history. For those who identify with them, flags are symbols of power, pride, and even resistance; for those who feel repressed by them, flags are symbols of domination and nationalism. They command loyalty, and for centuries have been critical tools of mobilizing popular support — and for crushing dissent.

Flags are just pieces of cloth. But the way they are used imbues them with tremendous significance. Each Iranian flag signifies a specific history and ideology, representing the political divides of the 90 million Iranians in Iran and 5 million Iranians in diaspora. At recent protests, many members of the Iranian diaspora were unsure what flag they should use. Many non-Iranians who showed up with the official Iranian flag in solidarity found themselves confronted by Iranians waving other flags — and expressing opposition to the official flag.

So what do each of Iran’s flags represent? And why do they provoke such strong emotions?

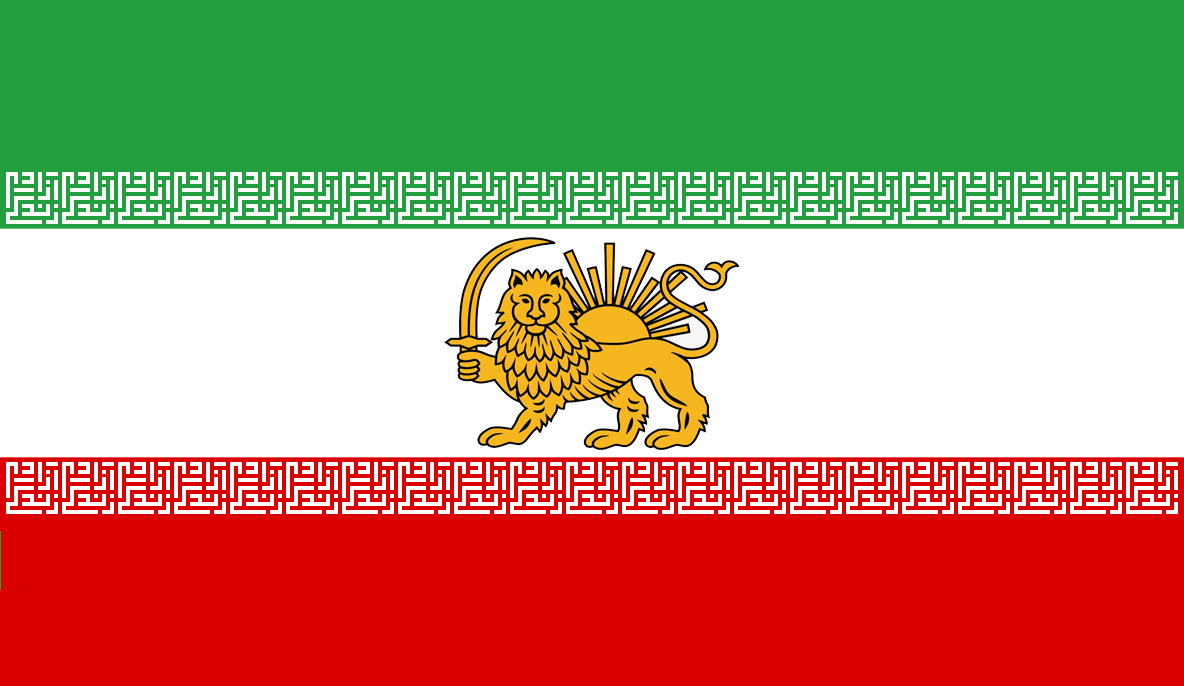

The Allah Flag

This is the official flag of Iran. It has been flown by Iranians inside Iran for nearly 50 years, and if you look for an Iran flag emoji, this is the one you find: 🇮🇷

After the 1979 Revolution, symbols of the Pahlavi regime were gradually removed. There was an open call to design a new flag, and an architect named Hamid Nadimi won the competition. Its central feature is a stylized emblem that reads both “Allah” — “God” in Arabic — and “La Ilaha Ill Allah” — There is No God But God,” the declaration of Islamic faith.

The Allah symbol did not exist before it landed on the flag. As Kimia Maleki explains, it was “created ex nihilo by an artist to accompany the novel idea it would crown: an Islamic Republic.” It is thus a uniquely Iranian symbol, closely tied to the Revolution and its aftermath.

Along the edges of the flag’s green and red bands, “Allah o Akbar” (God is Great) is written in Kufic script. Allah o Akbar is not only a religious expression; during 1979, it became closely related to the Revolution. When the Shah imposed a military curfew, people took to the roofs to yell the phrase, implying that God was higher than any tyrant. In 2009, Green Movement activists adopted this tactic, reinforcing the phrase’s political meaning.

This is the flag that Iranians have lived under and died for since 1979. Iranians of all faiths have been buried in it. Those who died in the Iran-Iraq War and the 1,000 Iranians killed in Israel’s recent assault were all laid to rest in coffins wrapped in this flag. For the 90 million Iranians inside Iran, this is the flag of their home country.

Critics attack this flag precisely because they see it as linked to Islamic Republic. Many Iranians have for decades opposed this flag because they say it lends legitimacy to an authoritarian state. Others oppose it because of its Islamic religious references, which they see as discriminatory against Iranians of other faiths — Jewish, Christian, Bahai, Zoroastrian, etc. — as well as against non-religious Iranians. Despite its official use, it remains controversial for many.

Outside the country, this flag is used to officially represent Iran. Iranians wave it at sporting events, for example.

But many in the diaspora shy away from using the flag because of its associations with the current Iranian government, especially those who live in countries in a state of conflict with Iran (like the US), where it could be perceived as an enemy flag.

For Iranians elsewhere, however, it is seen as a non-controversial national symbol.

This flag has also been waved by non-Iranians in solidarity with Iran, especially in the wake of Israel’s war. In June 2025, thousands protesting the war waved this flag as a symbol of anti-imperialist resistance, alongside Palestinian, Lebanese, and Yemeni flags, among others.

In the wake of Israel’s June 2025 attack on Iran, the flag has experienced a resurgence. Many increasingly associate the flag with national solidarity and unity in the face of enemy forces.

The 1980 Flag

Although the Allah flag is the most well-known revolutionary flag, the first design contest after the 1979 Revolution actually yielded a different symbol initially. Designed by Sadegh Tabrizi, this emblem was placed on Iran’s first post-revolutionary flag:

The symbol, however, was soon after discarded and replaced with the Allah emblem. It’s unclear why this happened, but it has been speculated it may be due to the emblem’s resemblance to a pentagram.

This flag has been largely forgotten and is never used in Iran or outside the country.

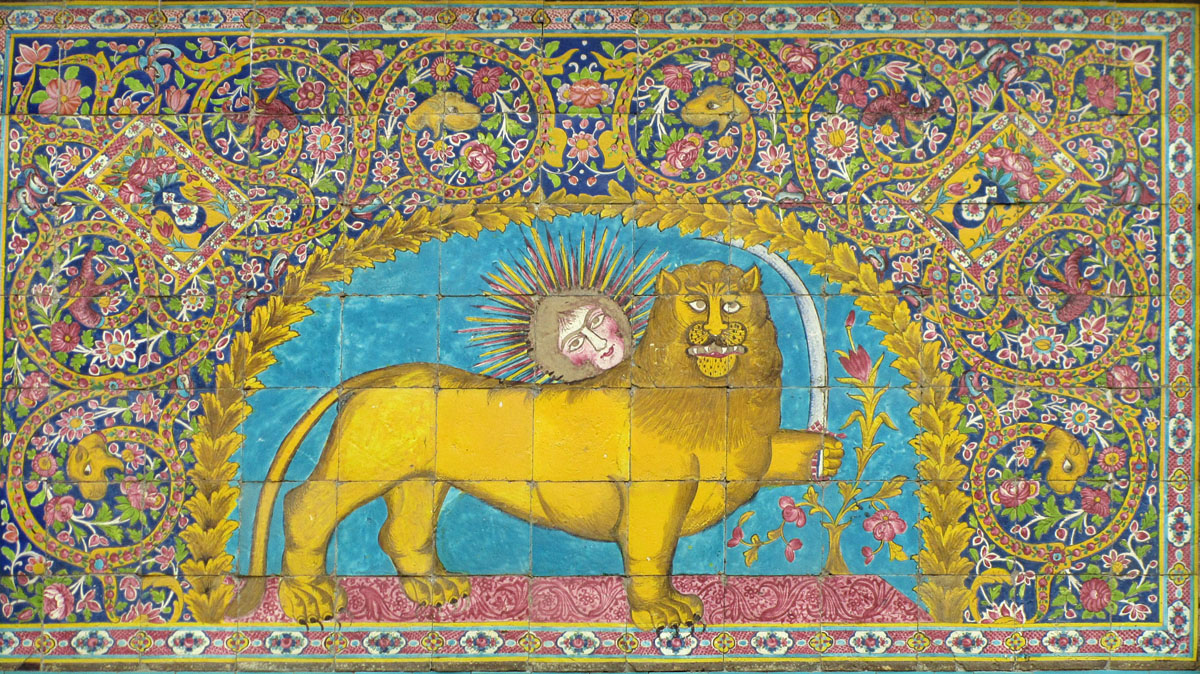

The Lion and Sun (Shir o Khorshid) Flag

This is the flag of Iran associated with the Pahlavi dynasty, which ruled the country from 1925-1979. The Lion and Sun emblem at its center has been associated with Iranian monarchy for centuries. The current form of the flag was standardized in the 1930s, after the coup that brought the Pahlavis to power, and has since become the official version.

This flag’s central symbol is the Lion and Sun. Its origins are unclear; some believe it is astrological in nature, with the Lion representing the Leo sign associated with kingship. The Sun is also linked to Imam Ali, the cousin and son-in-law of the Prophet Muhammad who is deeply revered by Muslims; the curved sword closely resembles the zulfiqar, Imam Ali’s famous sword.

Historian Afsaneh Najmabadi describes the symbol as uniquely bringing together “Zoroastrian, Jewish, Shi‘ite, Turkish, and Persian symbols … a condensation that has produced it as a most powerfully national emblem.”

For supporters of this flag, its connection to historic Iran is central to its importance. Iranians who left the country after the Revolution tend to identify with this flag, often associating it specifically with the Pahlavi dynasty that ruled before 1979.

In recent years, the flag has become closely associated with the monarchist movement, which supports overthrowing Iran’s government and installing the son of the deposed Shah on the throne. It is common to see this flag in cities with large monarchist factions, such as Los Angeles and London.

Supporters often argue that the Lion and Sun flag is a more inclusive version of Iran’s flag.

But its association with far-right monarchists has reshaped the flag’s significance; the fact that this flag was used at rallies supporting Israel’s attack on Iran have tainted it with a regime change agenda. Israel even named its war “Rising Lion” in apparent reference to the flag.

Similar to Derafsh Shahbaz and Derafsh Kaviani, two ancient royal emblems increasingly used by far-right Iranian monarchists and nationalists, this flag has rapidly changed in meaning. For many Iranians, this flag is too associated with the Pahlavi dictatorship — and its contemporary champions — to be salvageable.

But many Iranians who wave this flag also despise the Pahlavi dynasty. For them, this flag is a symbol of historic Iran, and not tied to any specific regime.

The Mujahedeen-e Khalq, an opposition party turned militant exiled cult, uses a distinct version of this flag, despite their longtime hatred of the Pahlavi dynasty. Their version shows the Lion and Sun emblem in a faded light yellow or “golden” color.

Similar to the monarchists, the MEK threw their lot in with a foreign enemy power; in the 1980s, they fought alongside Saddam Hussein when he invaded Iran, hoping to take control of the country with his support. The MEK failed and quickly lost popularity among Iranians.

Because of its association with the Pahlavi dictatorship as well as contemporary regime change agendas, the Lion and Sun flag continues to be deeply controversial.

A version of the flag used in the early 20th century showed the Sun with a feminine face, called Khorshid Khanom. Najmabadi argues that the sun lost its eyes, eyebrows, and hair as part of Reza Shah’s modernization drive, which promoted a militarized image of the nation, “leaving the symbolics of the modern Iranian state completely masculine.”

The earlier version featuring a much-larger emblem and the Sun with a face is never flown:

The Tricolor

This flag avoids the complications of other flags by removing all symbols and leaving behind just the tricolor. In doing so, seeks to represent all Iranians regardless of creed or political opinion.

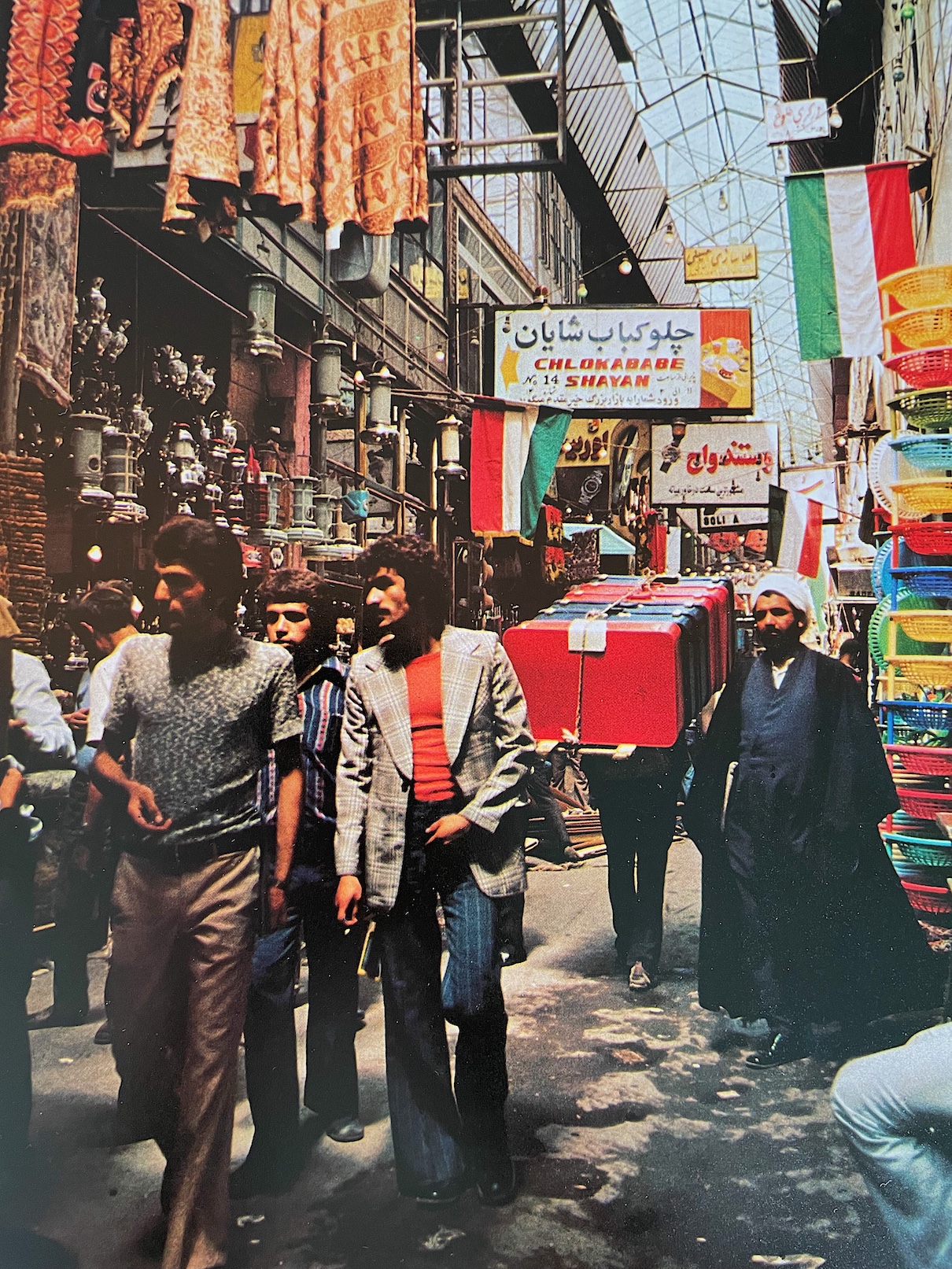

Before 1979, it was common to see this version used on banners across Iran. For public celebrations, Iranian cities were covered with the symbol-less tricolor, which was easy to mass produce.

In these photos from the 1970s by Roloff Beny, the tricolor can be seen decorating a bazaar and a boat in the Persian Gulf:

This flag was also raised by the Constitutionalist movement and the National Front party, associated with Mohammad Mossadegh. This flag is a way to acknowledge the diversity of opinions among Iranians while sidestepping political debate.

Detractors of this flag charge that it is too generic to work as a national flag. Because it lacks any symbol, it is difficult to identify the flag as Iranian. It could easily be confused for the flag of Hungary, which uses a similar design but reverses the colors.

But it is precisely this flag’s simplicity that makes it attractive to its supporters.

The Woman Life Freedom Flag

This is the newest addition to Iran’s flag debate. It emerged out of the 2022 protests in Iran that catalyzed around the progressive, feminist slogan Woman Life Freedom (Zan Zendegi Azadi — زن، زندگی، آزادی), translated from Kurdish Jan Jiyan Azadi (ژن، ژیان، ئازادی). The slogan became a powerful rallying cry after Mahsa Zhina Amini, a Kurdish woman in Iran, was killed while in police custody, leading to months of protests demanding greater freedom and political change.

It’s unclear who designed this flag, but it spread rapidly through social media. Its diffuse, grassroots, and non-hierarchical origin reflects the nature of the protests themselves.

The Woman Life Freedom symbol used in the flag is in Kufic script, one of the oldest forms of writing in the Perso-Arabic alphabet.

The Woman Life Freedom flag was popularized during global rallies in solidarity with the movement inside Iran in 2022-23. It was also used at rallies inside the country, such as this Baloch women’s protest:

This flag is linked with contemporary progressive movements, especially among younger Iranians who see the other flags as tainted by association with dictatorship. For supporters, this flag represents a way to ally not only with Iran’s people but also with domestic movements demanding a multi-ethnic, secular democratic state with equal rights for all.

Critics, however, charge that the symbol is so closely associated with a single movement that it’s hard to position it as representing the entire nation. Monarchist Iranians, meanwhile, consider any flag beside the Lion and Sun flag an insult.

If there is a political shift in the country in which new leaders recognize the Woman Life Freedom Movement as key to the change, it’s not unthinkable that this flag could be used more widely. But there have been many waves of protests in Iran, including the 1990s worker strikes, the 2009 Green Movement, the 2016-18 protests, the 2019 Aban Uprising, and the 2021 water protests. So choosing this emblem over others may be unpopular. If Iran were to adopt this flag, it would become the only country in the world with an explicitly feminist emblem.

So what flag should we use?

The complexity of the contemporary Iranian political landscape is reflected in the debates over the flag.

Iran is not alone in this situation; Vietnam, for example, has a similarly polarized political climate. The US-based diaspora generally uses the flag of South Vietnam, while the flag of united Communist Vietnam flies back home. The South Vietnamese flag has become increasingly associated with pro-Trump, far-right nationalism among Vietnamese in diaspora. This is similar to the issue facing the Lion and Sun flag.

The diversity of flags can feel confusing. Many Iranians in diaspora today grow up surrounded by different versions of the flag.

I grew up in Los Angeles. At many stores in Westwood, the heart of the Tehrangeles Iranian community, the Lion and Sun flag hangs on the wall, and at community parades it’s the version used. When we attended friendly sporting matches between Iranian and local teams, we waved the plain tricolor. And when we watched Iran play in the World Cup, or when I visited Iran, the flag that waved above us was the Allah flag. Inspired by the Woman Life Freedom protests, I’ve often posted the newest version on social media.

There’s nothing inherently wrong with having different flags. Flags are what we make of them, and changing flags is not uncommon around the world. Each flag acquires different meanings with the passage of time. Perhaps the best approach is one of tolerance and coexistence — recognizing that there are as many Iranian political opinions as there are Iranians, and this is reflected in the flag debate.

Some have even recently suggested possible new versions of the flag, combining existing elements or replacing them with new ones completely.

Maybe it’s time for a new competition to design a new, inclusive Iranian flag. But even that flag might come to acquire complicated associations over time.

Here’s a few suggestions I’ve seen recently. Feel free to suggest more designs in the comments!