The following is a guest post by Gulnoza Usmonova, a tourism educator and development expert. Originally from Uzbekistan, she earned her PhD in Tourism, Economics, and Management from the University of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria and consults on sustainable community-based tourism development and cultural heritage preservation across Central Asia and Europe.

***

Bukhara, Uzbekistan was once a living, breathing city. Now it is rapidly becoming something else.

State-led gentrification is reshaping its ancient quarters. Family-run bathhouses, teahouses, and workshops are giving way to boutique hotels and luxury spas. The city still looks like Bukhara. But it no longer feels like home for many who’ve built their lives there.

I first met Akbar years ago when I was working as a tour guide in Bukhara. I brought groups to historic bathhouses in the city I grew up in. Akbar was a third-generation hammam keeper; his family had run bathhouses in Bukhara since the mid-20th century. Over countless visits, I got to know his family and their deep connection to the space. The Bozori Kord hammam wasn’t just a stop on the itinerary, it was a place that radiated warmth, ritual, and belonging. Until all of a sudden, Akbar was forcibly evicted.

“It wasn’t just a business,” he told me by phone when I talked to him this spring: “It was part of who we were.”

Akbar’s grandfather opened the family’s first hammam in the heart of Bukhara’s old city. Bozori Kord Hammam was a simple yet welcoming place, tucked away in an ancient mud-brick courtyard. It wasn’t just a place to wash away the day’s grime. It was a sanctuary where locals unwound, shared stories, and rejuvenated.

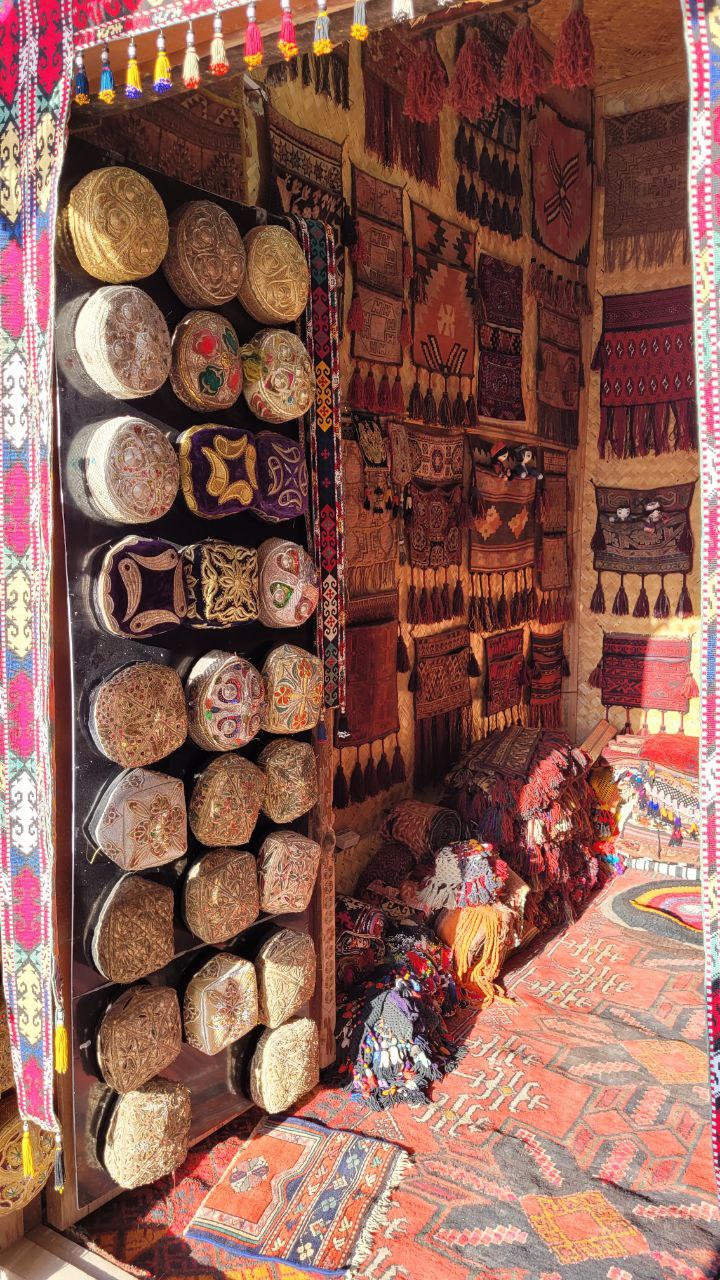

I still remember visiting Bukhara as a university student 15 years ago. The old city was alive with sound and color and narrow alleys buzzed with barter and laughter. Locals moved between open-air stalls selling everything from hand-thrown clay pots and embroidered suzani to wedding dowries of gold jewelry. The alleys of Payshanbi Bozori (Thursday Market), removed from the old streets of Bukhara, weren’t just commercial spaces; they were cultural arteries, pulsing with the voices of artisans, families, and traveling traders.

Back then, Bukhara still belonged to its residents. Today, those same streets are quieter, lined with tidy boutiques offering curated versions of local crafts priced for foreign visitors. The market’s organic disorder has been replaced by aesthetic uniformity. International chain hotels have crept in, their modern facades blending a little too seamlessly with restored madrasahs and trading domes.

This transformation is especially visible in the city’s three surviving hammams: Bozori Kord, Kunjak, and Sarrafon. Once embedded in the daily routines of Bukharans, these bathhouses have now been redesigned for tourism. Bozori Kord, previously a male-only hammam tucked behind the spice bazaar that catered to locals, now operates as a heritage attraction offering foreign visitors packaged treatments and souvenirs.

Kunjak Hammam, which historically served women and brides-to-be, is now mostly booked by tour groups. Locals rarely visit. Even Sarrafon, located in one of Bukhara’s oldest quarters, has been refurbished to meet upscale spa standards. The hammams have been physically preserved—but their function and accessibility has changed. They have been totally gentrified. What was once a shared public ritual has become a staged cultural experience.

When Akbar was a child, his father took the reins of the Bozori Kord hammam. He expanded it to meet growing demand. When Bukhara became a growing stop for international tourists in the 2010s, Akbar’s father embraced the transformation. He balanced the local community with the increasing number of tourists flocking to Bukhara. The city around them changed, but the hammam still thrived, carrying on centuries old traditions and balancing the needs of diverse clientels.

Since the Soviet era, most historic buildings in Uzbekistan—including hammams, madrasas, and caravanserais—have been considered state property. Even when used privately, these spaces were typically leased from local government bodies, a system that persisted after independence. Akbar’s family operated under long-term lease agreements issued by the municipal leasing and rental management office, under the oversight of the Department for Cultural Heritage.

“For decades we paid our lease on time,” Akbar explains. “It wasn’t owned, but it was understood to be stable—as long as we preserved the building.”

That understanding began to unravel in the late 2010s, when Uzbekistan’s tourism policy underwent a major transformation. In an effort to attract foreign investment and boost visitor numbers, the state introduced a wave of privatizations and public-private partnerships, particularly in heritage zones. Local administrations, now under pressure to demonstrate economic performance, began viewing cultural sites as lucrative real estate.

In 2022, Akbar’s lease wasn’t renewed. Local officials reclassified similar properties across the city for auction with unclear criteria. What had once been a stable, if imperfect, relationship between public institutions and private caretakers was replaced by market-driven transactions where cultural significance was forfeited for commercial potential.

“For three generations we ran the hammam. My father led the Bozori Kord Hammam from 1987,” Akbar recalled. “In 2022, we could not receive a lease agreement for renewal. We were promised one. But then found out the land and hammam area were put on auction without reasoning or explanation. We were given no warning: nothing.”

Instead of a renewal, Akbar was encouraged to participate in the auction process with assurances that it was just a formality. But when bidding escalated, the price soared beyond his reach. He suspects there were silent agreements among officials in Cultural Heritage Management and the Leasing and Rental Center Management aimed at monetizing historic land.

Staged Authenticity and the Commodification of Culture

Uzbekistan has invested over $1 billion in heritage restoration projects since 2017, transforming cities like Bukhara, Samarkand, and Khiva into polished, visitor-friendly cultural hubs. These efforts are supported by organizations like UNESCO, which recognizes Bukhara as a World Heritage Site. These initiatives aim to preserve architectural splendor. But they often do so at the expense of the cultural practices of local communities.

Under urban renewal policies, historic districts are rezoned to accommodate high-end tourism and commercial enterprises. Families like Akbar’s have been forcibly displaced, their businesses either shut down or repurposed into spas catering exclusively to international visitors.

“The new owner of the hammam has remade it under luxury spa standards. But we tried to preserve the authenticity of the 16th-century Bukharian hammam as it was. We were not allowed to change anything since it was under UNESCO protection. It seems that does not matter anymore,” he told me.

Akbar and his family spent a year in court, fighting to reclaim their hammam, but to no avail: “We had to give up and leave.”

Uzbekistan’s efforts to attract tourists have led to the careful curation and staging of its historic centers. Restoration projects, while visually stunning, often prioritize aesthetics over authenticity. Cities that once bustled with life increasingly resemble open-air museums. Traditional neighborhoods have become sanitized tourist zones where locals are pushed to the periphery.

This phenomenon aligns with MacCannell’s (1973) concept of “staged authenticity,” where destinations present an idealized version of their culture rather than an organic reality. Historic centers become performance spaces, reducing local engagement and turning residents into actors in their own mahallas (neighborhoods). Hammams, once essential communal spaces for Bukharans, are rebranded as exclusive wellness retreats for foreign tourists. These spaces are stripped of their historical significance, function, and accessibility to local communities while being marketed as “authentic” to the visitors who displace them.

This commodification erodes the sense of place that defined Bukhara for centuries. The decorative facades remain, but the essence of cultural identity is diluted as local businesses are replaced by standardized global hospitality models.

“Bukhara is a sacred spiritual city. Its gems are not five-star hotels and staged tourist experiences—it is people who belong here, who know the essence of home and can keep it alive,” Akbar told me as he surveyed changes across the city.

Meanwhile, local authorities are moving fast to reshape what’s left of the old city’s edges. As part of the Eternal Bukhara project, they are demolishing a vast area to replace buildings with high-rise hotels. Many of Bukhara’s major Soviet-era architectural heritage will be destroyed for modern developments pretending to be ancient.

The rapid shifts in ownership and policy create instability, making it nearly impossible for small, family-run businesses to sustain their livelihoods. And they enrich the same local government actors that are displacing locals.

Is What’s Good for Tourism Good for Locals?

In cities once celebrated for their community-based mahalla systems and informal but deeply rooted neighborhood structures, tourism has triggered rapid gentrification. In Samarkand, entire mahallas have been razed to make way for pedestrian zones catering to tourists. Residents living near Registan Square often report blocked access to their homes during government events or international festivals. The widening of roads and refurbishment of historic cores frequently comes at the cost of private housing, with compensation mechanisms opaque or insufficient. A recent report by the International Partnership for Human Rights highlighted that over 1,800 homes were affected by urban redevelopment in Samarkand and Bukhara between 2017 and 2022.

The artisan workshops of Khiva, once a haven for living craft traditions, are being converted into boutique galleries and luxury retail outlets. Locals, many of whom lack legal title to the homes they’ve lived in for generations, are vulnerable to eviction and rising rents. While tourism has increased jobs and services, these gains are not evenly distributed. Most employment remains seasonal and concentrated in low-wage sectors such as hospitality and retail. Women, youth, and older residents are often excluded from the benefits of tourism due to limited access to training, land, and capital.

To mitigate the negatives of tourism-led gentrification, Uzbekistan must pivot to people-centered policies. Authorities should designate residency-protected zones in historic districts to limit the transfer of property ownership to outside investors, especially in areas of high tourism value. Priority should be given to local families and cooperatives, reducing speculative buying and preserving social fabric.

Rural destinations such as those in Jizzakh, Surkhandarya, and the Aral Sea region should be protected through community land trusts or cooperative ownership models. These frameworks ensure that tourism development rights and revenue streams remain in the hands of local stakeholders. In the Kyrgyz Republic, similar models have helped CBT groups in Kochkor and Karakol negotiate better terms with tour operators and investors.

Uzbekistan’s Nuratau Mountains, Fergana Valley, and Aral Sea region, where community-based tourism (CBT) is expanding, would benefit from similar legal protections ensuring that village land remains under local ownership and is not sold to large hotel chains or private investors.

Tourism revenues accounted for nearly 5.2% of Uzbekistan’s GDP in 2019, with projections to reach 7% by 2030. But if growth continues in its current extractive model, the increase in tourism will only exacerbate deep social inequities. Empty heritage zones repackaged for consumption will neither foster long-term sustainability nor cultural vitality.

The case of Bukkara’s disappearing hammams underscores the unintended consequences of aggressive urban redevelopment—displacement and heritage loss in the name of tourism.

Akbar now works in a different hammam, still within Bukhara’s old city. The bathhouse had been abandoned for years—its pipes rusted, its ceilings stained with time—until Akbar and a few like-minded friends decided to bring it back to life. They pooled their savings, secured a lease, and began the slow process of renovation, sourcing traditional materials where possible and learning to adapt where they couldn’t. The new hammam might lack the grandeur of the one his grandfather managed, but it offers continuity, something in short supply in Bukhara today.

Yet Akbar is, in many ways, an exception. Across Bukhara, Samarkand, and Khiva, many artisans and small tourism entrepreneurs weren’t as fortunate. When historic neighborhoods were redeveloped or rezoned, few were able to find affordable new spaces or secure permissions to reopen. Some moved away entirely, others shifted to different trades, and a few left the industry altogether, taking with them generations of accumulated knowledge.

Akbar’s story offers a glimpse of an alternative model where unused heritage infrastructure is repurposed by those with long-standing ties to the trade, and where continuity is valued as much as preservation. But without targeted policies such as preferential leasing, financial support for adaptive reuse, and recognition of intangible heritage, these stories will remain isolated successes. What Bukhara needs is not just restored facades for tourists, but restored ecosystems for the people who give them meaning.

References

BBC Travel (2025). “The Dark Side of Uzbekistan’s Tourism Boom.”

Caliber.az (2025). Uzbekistan’s Tourism Ambitions Clash with Historic Preservation.

Çelik, N. (2021). Urban Renewal and Local Participation: Lessons from Turkey’s Heritage Cities. Journal of Sustainable Tourism.

ElKhatib, N. (2020). Gentrification and the Loss of Cultural Identity in Marrakech’s Medina. Journal of Urban Development Studies.

Eurasian Economic Review (2024). The Role of Foreign Investment in Central Asian Tourism Growth.

Eurasianet (2024). UNESCO Says Uzbekistan Broke Promises Over Bukhara Development.

Global Hand. Central Asia, Kyrgyzstan – Creating value for all: Community-based tourism.

International Partnership for Human Rights (IPHR). (2022). Human rights in Uzbekistan: Ongoing concerns related to freedom of expression, assembly, and forced evictions.

Javakhishvili, T. (2021). The Impact of Short-Term Rentals on Housing Affordability in Tbilisi. European Journal of Urban Economics.

MacCannell, D. (1973). “Staged Authenticity: Arrangements of Social Space in Tourist Settings.” American Journal of Sociology.

UNESCO (2021). Bukhara: World Heritage Preservation and Economic Development Report.

Uzbekistan Heritage Preservation Council (2025). Gentrification and the Future of Uzbek Cultural Sites.

World Monuments Fund (2022). Tourism and Heritage: Managing Cultural Destinations Sustainably.

Yamamoto, R. (2022). Collective Land Ownership Models for Indigenous Tourism Sustainability in Thailand. Asian Development Review.

Zukin, S. (2010). Naked City: The Death and Life of Authentic Urban Places. Oxford University Press.