The following is a guest post by Manar Heikal, an Egyptian lawyer and researcher whose writing explores intersections of law, memory, and diaspora. She holds an LLB in Civil and Islamic Law from Cairo University and a BA in History and Public International Law from the American University in Cairo.

***

For years, the Iranians of Cairo existed for me only as names whispered in family anecdotes, entries in faded ledgers, faces in aging photographs.

You won’t find much about them in textbooks. There are no heritage signs, no official archives, no plaques. Our story was something quieter. More intimate. Preserved in the cadence of a lullaby, the rustle of old Persian newspapers forgotten in wooden drawers, the yoghurty dough served with every meal.

In the afternoons, my grandmother would cup rosewater in her palms and pat it into freshly washed linens. The room would sweeten, the air pearled with steam, and for a moment a country we had no passports to prove our connection to gathered at our home in Cairo: visible, then gone. That was how Iran arrived in our house; not on maps or in the straight lines of textbooks but in vapors, aftertastes, and sounds that refused to sit still.

I used to think identity was something you inherited, something stored in blood and documents. But my grandmother Hanyeh taught me something else: that you can carry a place inside you so deeply it becomes inseparable from who you are. Memory can be a kind of citizenship too.

She was born in Cairo in 1932. But she never let Egypt eclipse the Iran she’d inherited. Her father, Rahim Zahedi, and her mother, Golreez Hossein, had come from Tehran and before that, Hamedan. Her older brother was born there too.

My grandmother took quiet pleasure in noticing Persian threads through our Egyptian lives. Backgammon, tawla, wasn’t just a pastime. “That’s ours too,” she’d say, half-teasing, half-triumphant. And when she heard Egyptians call out their dice rolls — yek, do, se, chahar, panj, shesh — she’d smile knowingly. Because of backgammon’s Iranian origins, people across the Arab world count their die rolls in Persian, though they often assume the words are a kind of secretive code. “They don’t even realize they’re speaking Persian,” my grandmother would say.

The Iranian legacy in Cairo doesn’t raise flags or demand attention. It’s quieter than that. You have to look for it in door frames, in the way certain prayers are whispered differently, in the way molokhia tastes faintly of saffron when made in an Iranian kitchen in Cairo.

The Iranians who arrived here, merchants, artisans, dreamers chasing Cairo’s rhythm, layered Iran softly over Egypt’s own pulse, careful not to disturb what was already there. In el-Gamaleya, in Muski, in the shadowed alleys of el-Azhar, and Abbasseya their legacy lingers.

I walked those neighborhoods often, long before I understood what I was looking for. At first only piecing together my own family story, not realizing I was learning how memory survives.

The history of the Iranian community in Cairo is a story of cultural fusion. At its height at the turn of the 20th century, the community numbered some 4000, a figure documented in Mohamed Yadegari’s study on Egypt’s Iranian settlement, pieced together from a community paper, a modest figure by demographic standards, but a significant one in cultural life. They left traces in places one might not expect: in Persian-language newspapers like Hekmat, Chehrnameh and Parvaresh, in literary salons and charitable organizations, and in Cairo’s marketplaces, where their carpet shops became landmarks. Gamal Abdel Nasser, Egypt’s most iconic modern leader, married Tahia Kazem, the daughter of an Iranian immigrant who once worked for Iranian rug merchants in Khan el-Khalili.

Archives of Grandeur

In my own home, we knew we were of Iranian descent. But so many generations had passed that we had few friends from our community. I began wandering Cairo seeking clues to my questions: What did their lives look like along its winding streets? How did they move through this city, and how did the city absorb them?

That curiosity led me into archives, old newspapers, and stories half-remembered by relatives. The pages of the 1929 Egyptian Commercial Directory reveal an Iranian presence, leaking through scattered Persian surnames (Namaki, Shirazi, Fazlollah, Esfahani, Tabrizi, Yazdi, Mishki, Kazrouni) listed among carpet dealers, importers, and warehousemen.

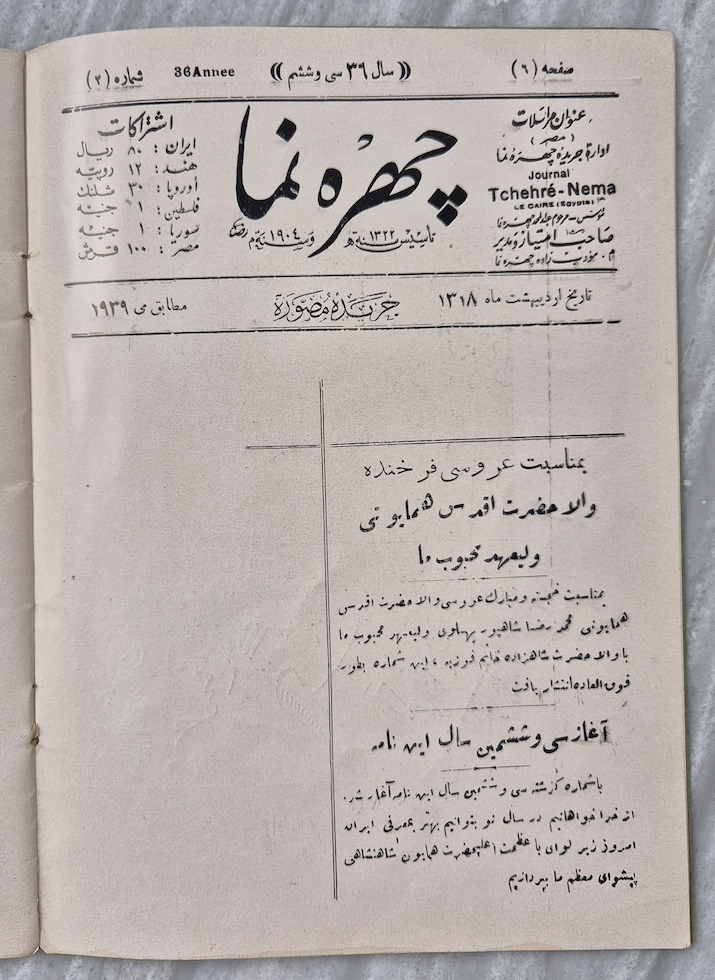

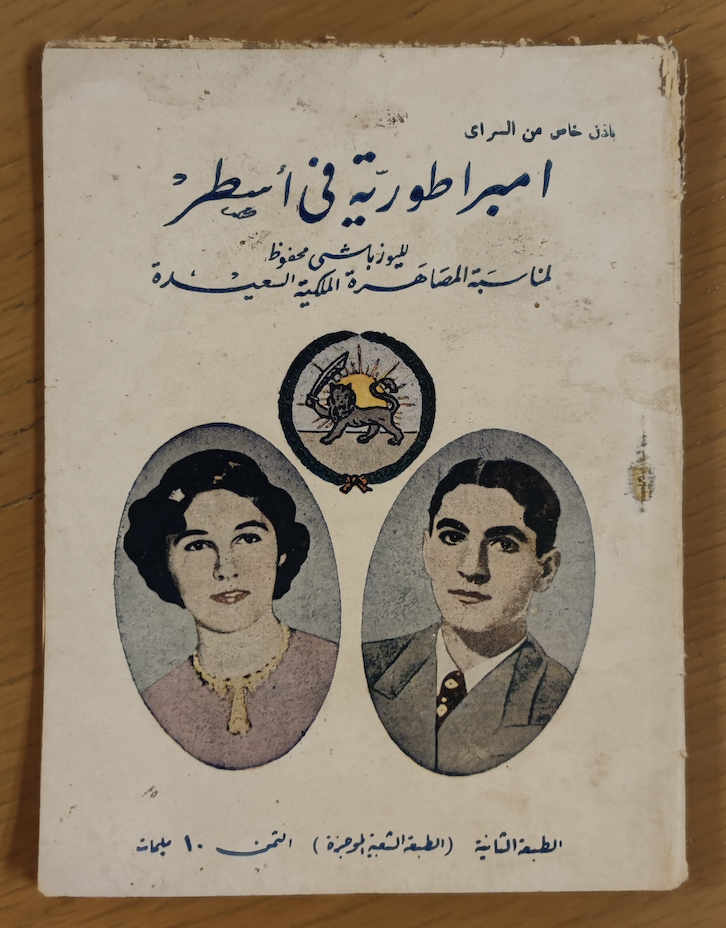

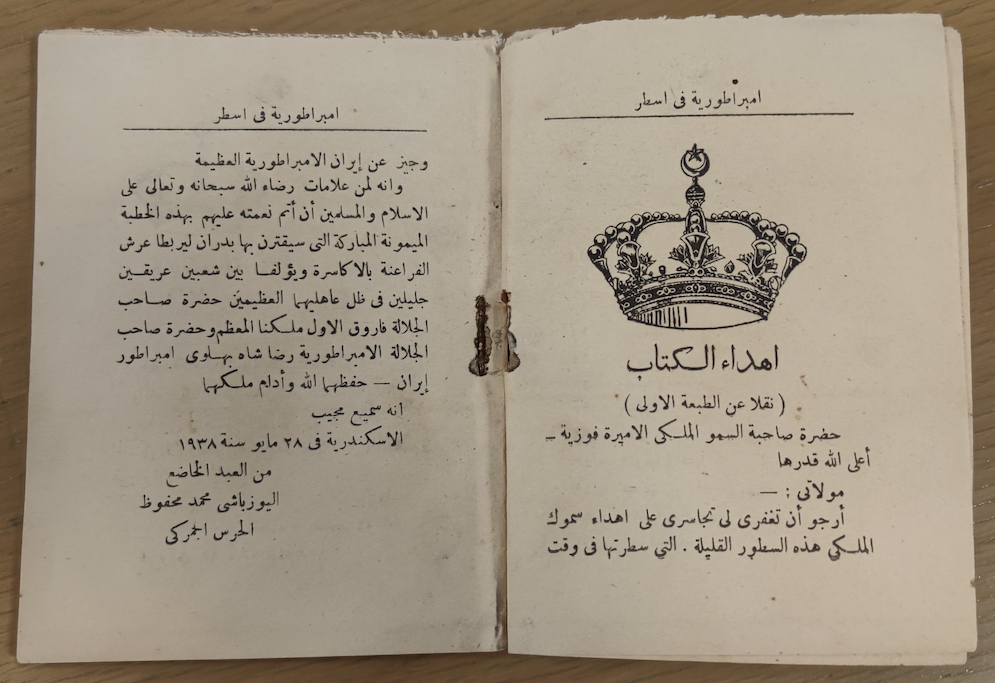

It was through my grandmother’s recollections that I first heard of a Persian-language magazine once circulated within Cairo’s Iranian community. It had been vital: a lifeline, she said, for a diaspora trying to make sense of itself in a place both foreign and familiar. Years later, almost ceremoniously, she handed me the only copy she had kept of a special edition of Chehrnameh, printed in Ordibehesht 1318, April or May of 1939, marking the royal wedding of Iranian Crown Prince Mohammad Reza Pahlavi and Princess Fawzia of Egypt.

The issue had been preserved by her father; wrapped, protected, and kept in perfect condition, as though he had always known its value would outlast the occasion itself.

Chehrnameh was the longest surviving Persian publication in Egypt, beginning as a journal and later on as a magazine. It stopped publishing in 1959. Hekmat was the first Persian publication in Egypt and in an Arab country, founded in 1892 by Mirza Mohamed Mehdi Khan Tabrizi, an Iranian Turk from Tabriz known as Ra’is al-Hokama’ and later Za’im al-Dawla, settled in Cairo in 1891 after a stint in Istanbul, where he worked with the Persian paper Akhtar. He edited and largely produced Hekmat on his own press with a run of almost twenty years.

Hekmat spoke against despotism and for “freedom and law,” circulating ideas that fed into the Constitutional Revolution of 1905-11, he shielded contributors’ identities under Iran’s strict press bans, a caution remembered by Egyptian writer Abbas Mahmoud al-Akkad, who described Tabrizi’s meticulous care for manuscripts in his book Rejal ‘Araftahom (Men I knew). Beyond journalism, in 1903 he published Miftah Bab al-Abwab, a polemical attack on Babi and Baha’i doctrines. Half a dozen other Persian publications were also published in Cairo. They catered to a community that grew in the late 19th and early 20th century. Many Iranian merchants and artisans decided to make Cairo and Alexandria their permanent home after the 1869 opening of the Suez Canal, which boosted Egypt’s economic and commercial significance.

Among the Iranian community members who rose to prominence in the Egyptian administration was Mohamed Ali Namazi Pasha, who served as Minister of Transportation in 1949–50 and briefly as Minister of Justice in 1952. Born in Cairo to an Iranian father from Esfahan and a Circassian mother, he descended from a family of carpet traders, the youngest after four sisters. The family name itself carried a story: as his grand nephew Mahmoud Elnahas tells it, an ancestor in Esfahan once held his prayer even as a thief emptied his home, and from that act of devotion the name Namazi “the steadfast in prayer” endured.

Namazi Pasha’s own life carried that quiet persistence. He studied law at Fuad I University (what would later become Cairo University), rose from public prosecutor to a leading figure in the State Council, and in 1949 was awarded the title of Pasha. As transport minister, he oversaw the railways at their peak and even weighed the idea of a Cairo metro, shelved until decades later.

In April 1950, the Arab League chose him to help draft the statute of an Arab Court of Justice, a project that gestured toward pan-Arab unity in law. And in the fraught aftermath of the Cairo Fire of January 1952, he was entrusted with the Ministry of Justice, tasked with steadying the state through legislation. His career stitched together law, infrastructure, and the Arab project, a discreet but enduring imprint of Iranian descent at the heart of Egypt’s modern state.

Iranians didn’t only enter Egypt’s government; they also arrived as distinguished guests. Walking through the bustling streets of Dokki one day, my mother turned to me and said, almost in passing, “Did you know that Mossadaq Street is named after Mohammad Mossadegh, the Iranian Prime Minister?”

Mossadegh’s historic visit to Cairo had been on November 20, 1951, a day woven with the fervor of shared purpose. Egyptian Prime Minister Mostafa El-Nahhas Pasha had invited Mossadegh after his celebrated defense of Iran’s oil nationalization at the United Nations. Crowds surged through the streets to greet him, waving banners inscribed in Persian and Arabic: “Long live Mossadegh” and “Long live the leader of anti-imperialism.” Egyptians lifted him onto their shoulders, carrying him triumphantly to his car as he made his way to Abdeen Palace to sign the guest register, every step echoing a shared defiance against foreign control.

Al-Ahram newspaper hailed his arrival, declaring, “Mossadegh has won freedom and dignity for his country,” while proclaiming a bond between Iran and Egypt as both nations took up “the sacred duty of freeing themselves from the shackles of colonialism.” It was reported that two million people had lined the streets, chanting not only for Mossadegh but also against British imperialism – a scene that undoubtedly inspired the nationalization of the Suez Canal just a few years later.

Mossadegh met with King Farouk and feminist leader Doria Shafik. Students at the Faculty of Fine Arts created a sculpture in his likeness, presenting it to him as a gesture of admiration. His visit carved itself into Cairo’s streets and memory, a reminder of a shared struggle for sovereignty and respect.

Only a year later, Gamal Abdel Nasser came to power in a coup, promising a new revolutionary order in Egypt. He followed in Mossadegh’s footsteps by nationalizing the Suez Canal.

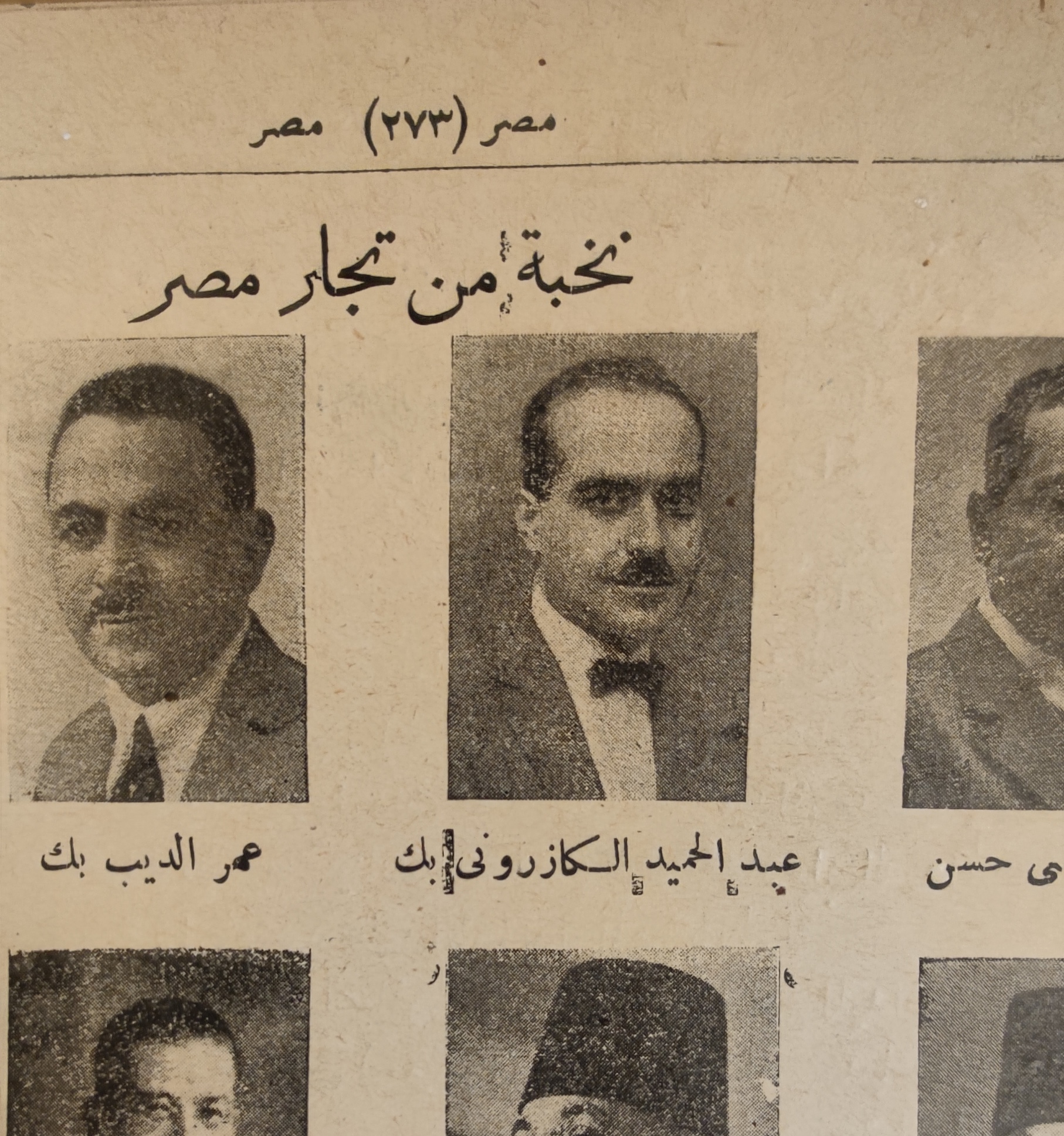

Nasser’s wife, Tahia Kazem, was from the community. Her father had come to Egypt from Iran and later owned a rug shop on Souk al-Samak al-Kadim, where many Iranian families owned stores. Nasser sought her hand in marriage in 1944. The story goes that her father sought the blessing of the head of the Iranian community, Abdelhamid Kazrouni Bek. I soon realized that this man was a key figure for understanding our community’s history.

The Cairo Kazrounis

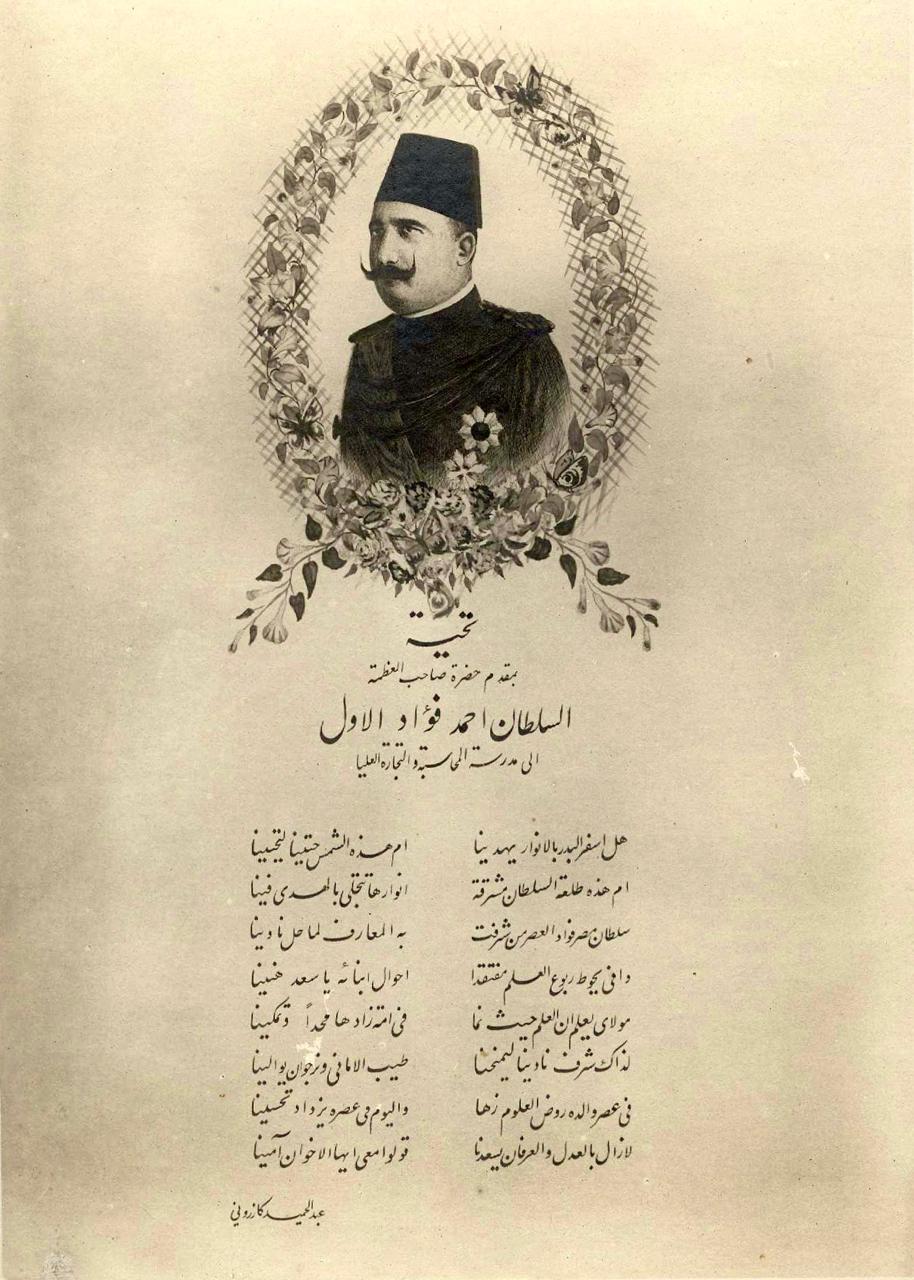

The last recognized head of Cairo’s Iranian community, Abdelhamid Kazrouni Bek, stood at the intersection of commerce and civic life. At King Fuad I University he graduated top of his class from the Faculty of Commerce. As valedictorian, he delivered a speech that included a poem honoring the university’s founder, and in recognition of his achievement, King Fuad presented him with a gold watch.

Nasser’s wedding wasn’t the only Iranian-Egyptian partnership Abdelhamid was involved in. He was also present at the wedding of Princess Fawzia and Crown Prince Mohammad Reza in 1939, pointing to his key role as a mediator for the community.

Abdelhamid’s story doesn’t sit apart from the broader Iranian experience in Cairo; it moves with it. He was one of the founding members of both the Iranian Charity Organization, which continued to operate after his death in 1962, and the Iranian Community School, closely involved in the steady work of keeping a community intact. As president of the Iranian Chamber of Commerce, he carved out a space not just for profit, but for permanence; proof that Iranians weren’t passing through, they were building something.

In coming to Cairo, Abdelhamid’s father, Abdelkarim extended a lineage that sprawled across the Indian Ocean. The Kazrouni carpet business in el-Azhar, run alongside his two sons, was the Cairo chapter of a much older story. Their roots ran through Madras, where ancestors had once managed a thriving trading depot.

He later established a small carpet factory in Shiraz, following in the footsteps of his family, who had founded the Kazrouni factory in Esfahan. That Esfahan factory was proudly featured in a 1939 issue of Chehrenameh. Abdelhamid, in turn, sought to adapt production in Shiraz to Egyptian tastes, designing rugs specifically for his shops in Cairo. The family’s relationship to commerce was inherited, lived, and recalibrated with each border crossed.

Over time, the Kazrouni name threaded its way through the bazaars of India, the ports of Turkey, the alleys of el-Azhar, and the merchant districts of Iran. What emerged wasn’t just a network, but a diasporic rhythm that moved fluidly between nations without ever quite settling into one.

By the time Abdelhamid was born, Iranians in Cairo were no longer newcomers. Their presence stretched back to the mid-19th century, to the reigns of Saeed Pasha and Ismail Pasha; eras when Egypt, newly tethered to Europe through the opening of the Suez Canal, had become a lure for traders, artisans, and hopeful émigrés. The cotton boom, the promise of infrastructure, and the ease of movement drew people from across the region.

Among them was Abdelhamid’s grandfather, Haj Mohamed Hassan Kazrouni, who arrived during the reign of Mohamed Ali Pasha. He began with indigo, a prized dye then, and eventually moved into textiles. Their origins were in Kazeroun, a town in southern Iran known more to merchants than to mapmakers, but whose sons could be found in souqs from Basra to Bombay.

The Kazrouni carpet shop on al-Hamzawi Street was more than just a family business; it was their shared project, their stage, and in many ways, their inheritance. They built on what their father had begun, expanding not only their commercial footprint but also their place in the city’s social fabric. Together they acquired properties, including a grand shop on Kasr al-Nile Street and a handsome home in Zamalek, and transformed their living space into a gathering point. Come Nowruz, the Persian New Year, their doors were open.

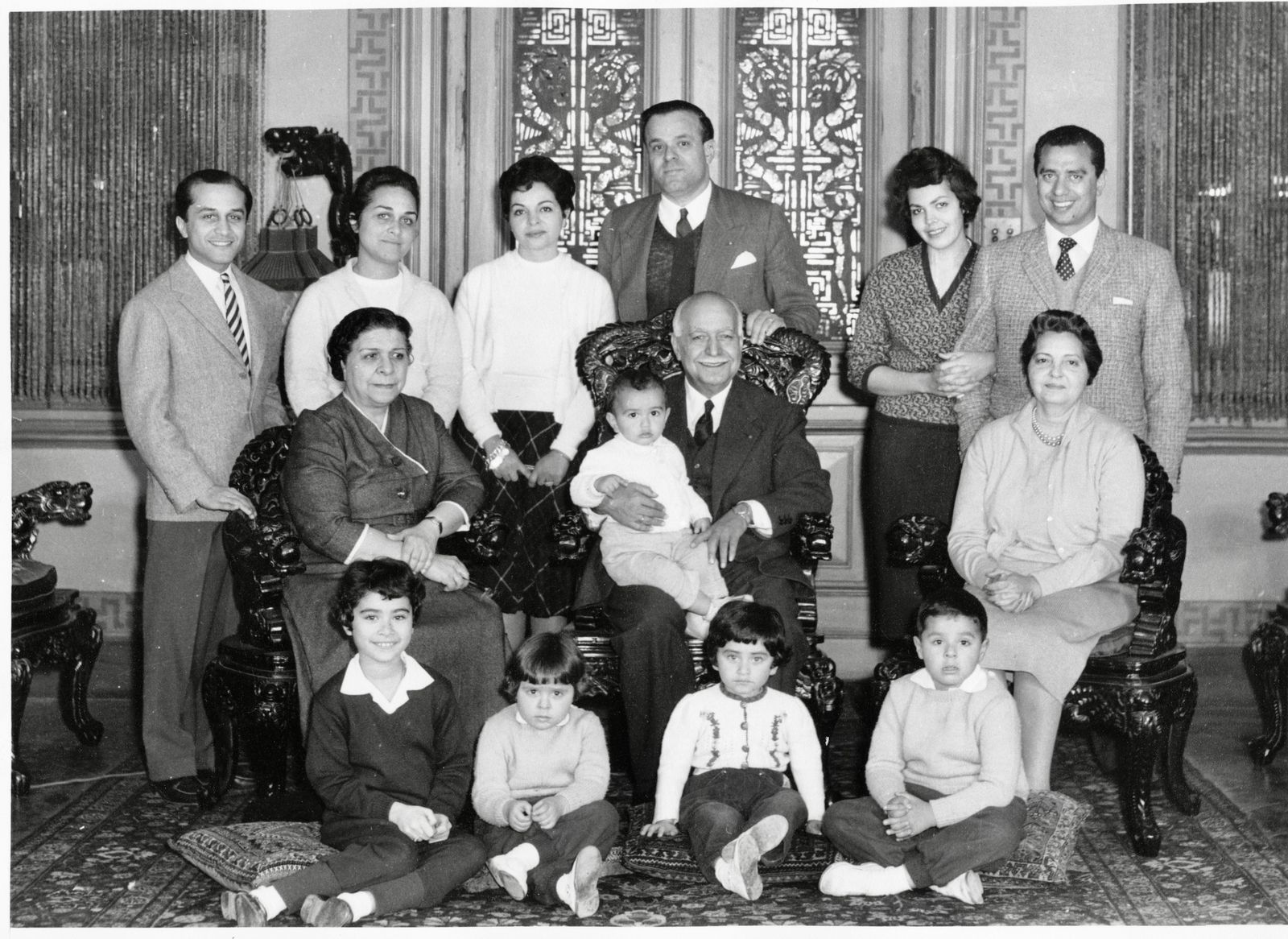

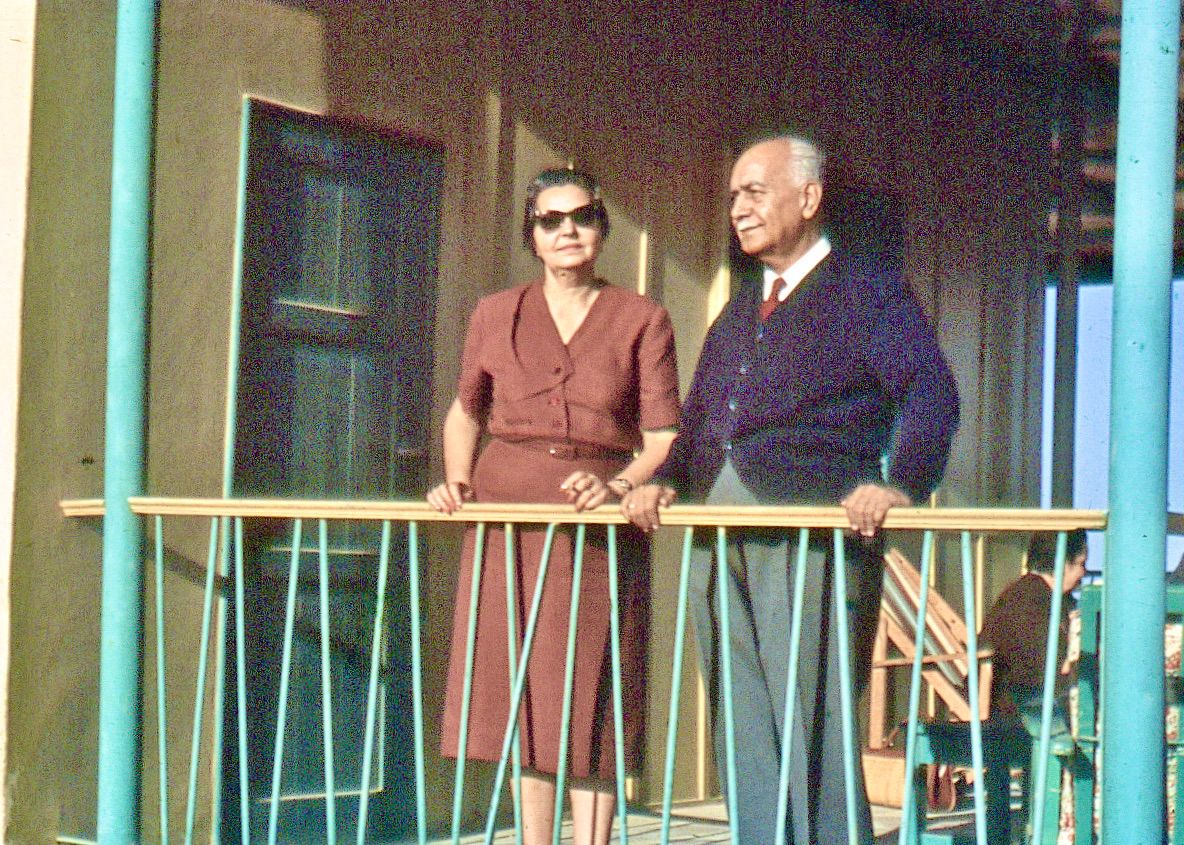

That Zamalek home remains in the family to this day. On a warm afternoon in July 2022, I found myself seated in its softly lit salon with Nazly, Abdelhamid’s daughter, her nephew, and a few of Abdelhamid’s great-grandchildren, who wandered in and out of the conversation.

Now in her eighties, Nazly carries her memories not as nostalgia, but as quiet certainties, details recalled with the clarity of someone who’s had time to sit with the past. The food on the table she served her family told a quiet story of belonging. Saffron-scented rice and Persian kebabs were served alongside molokhia, kofta, and Egyptian pickles. Each meal a subtle act of cultural blending. And always on the table, chilled and poured with care, was dough, the yoghurt drink from Iran that reminded them of another home.

Abdelhamid’s kitchen became a space where Iranian and Egyptian traditions didn’t just coexist, they conversed, complemented, and enriched each other.

Her father’s rise to becoming a trusted figure began with his 1927 appointment as a judge in the Mixed Courts, which settled disputes between Egyptians and foreign nationals. This role demanded the ability to navigate overlapping worlds. Without formal courtrooms, much of the work unfolded in offices and over correspondence, through quiet deliberations rather than public hearings.

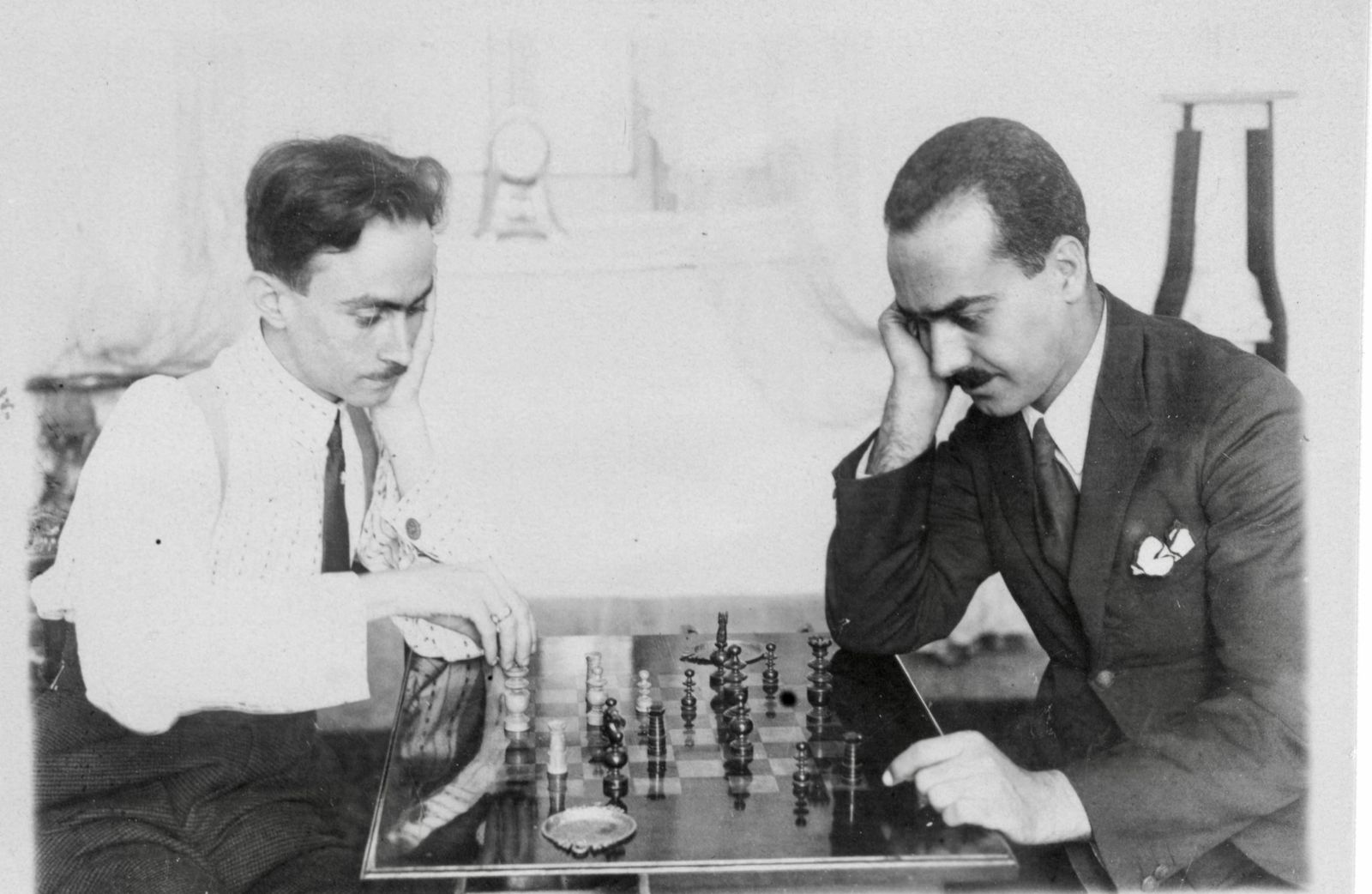

He was a trusted community leader that Iranian merchants in Cairo could turn to for guidance when tensions arose with Egyptian authorities. Beyond his judicial and communal role, she describes him as someone who loved life and activity; he had a passion for cars and for hunting, and in 1938 he became a founding member of the Royal Egyptian Shooting Club in Giza.

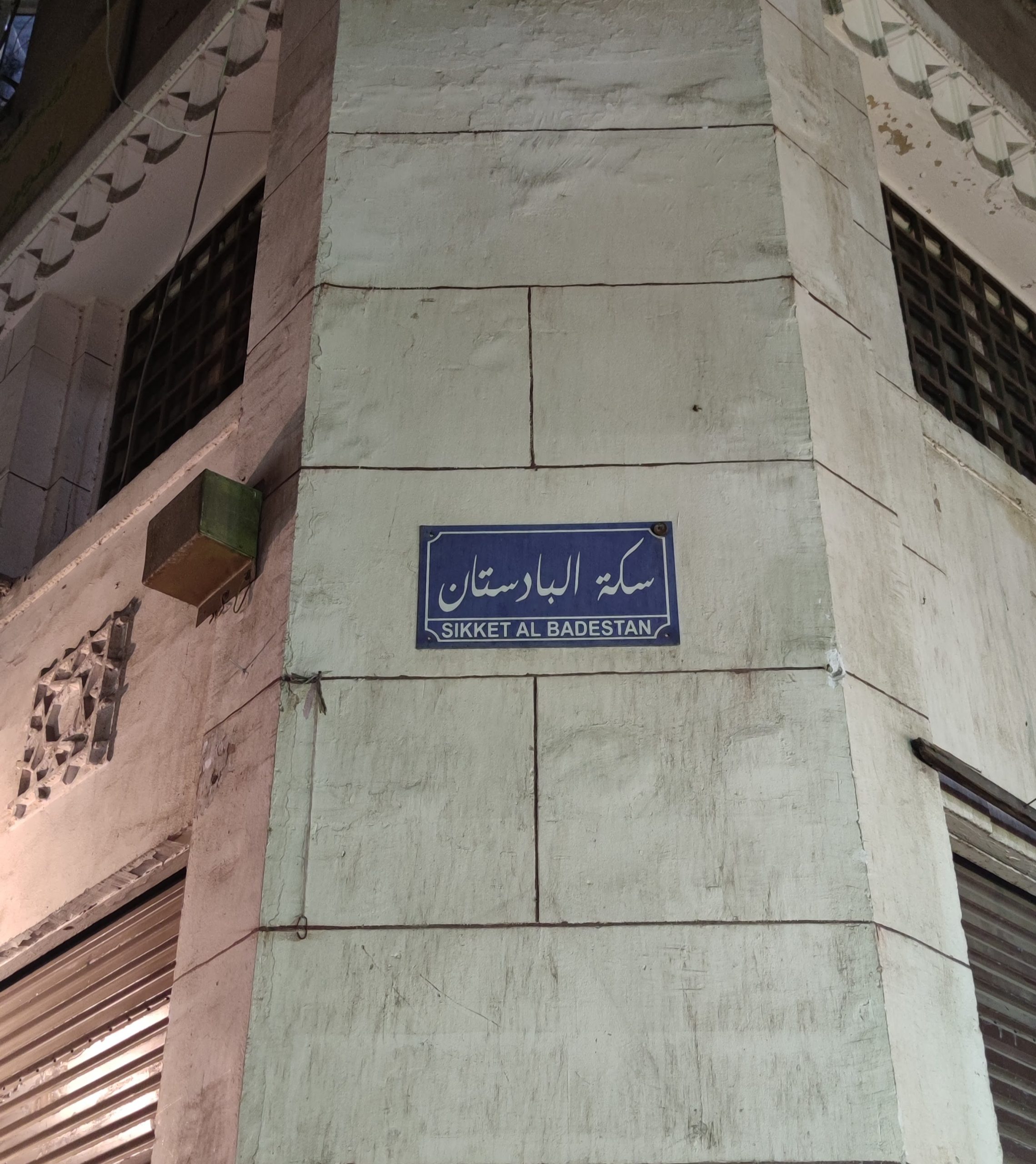

Like many prominent expat families in Cairo, the Kazrounis were more than merchants; they were quiet cultural diplomats. The Kazrouni shop on al-Hamzawi Street, in the heart of el-Azhar, was a place where culture, commerce, and community met. They also maintained a space on Sikkat al-Badistan, the narrow street in Khan el-Khalili once known for its Iranian traders.

In the Nile Delta city of Al Beheira, Abdelhamid’s ambitions took on a more tactile form. In the village of Naqraha near Damanhur, he founded what would become Egypt’s first mechanized rug factory; a curious marriage of Iranian craftsmanship and industrial Egypt.

Then came the era of nationalization. Like so many private ventures, the Kazrouni rug factory was absorbed into the state’s machinery; rebranded, bureaucratized, and folded neatly into the Egyptian Endowments Authority. Its founder’s name was quietly set aside. Yet the looms kept turning.

Today, the factory’s prayer rugs line mosques from Cairo to Aswan, offering worshippers a place to kneel, unaware of the journey woven beneath them. Like much of the Iranian presence in Egypt, the legacy is there, but hidden in plain sight. The threads endure, silent but insistent, carrying with them the imprint of a heritage that once traveled from Kazeroun to al-Beheira and, without making a sound, settled into the fabric of Egyptian public life.

A Fading Legacy

As the generations passed, borders became tighter and movement harder. Fewer Iranians made their way to Cairo. And in Nasser’s Egypt, announcing foreign ties became taboo. The community’s institutions slowly faded.

Places like Tekiyya Hussainiya “the Persian Tekiyya,” as the neighbors called it — that once hosted the Muharram mourning rituals of the Iranian community shut their doors. Rashid Rida, the Syrian-born Egyptian thinker and editor of al-Manar magazine, records that the Tekkiya was located in al-Hamzawi quarter near el-Azhar. ʿAli Mubarak, the 19th-century Egyptian administrator and historian, noted its presence in his encyclopedic al-Khitat al-Tawfiqiyya among Cairo’s religious institutions. Al-Akkad later recalled that Tabrizi himself had invited him to witness the Ashura rites inside, an unusual honor given how difficult it was for Egyptians outside the community to gain access.

The crooked al-Hamzawi Street just off the flare and frenzy of Khan el-Khalili doesn’t look like much today. But it once hosted a soft flood of ritual and sorrow, a grief that had traveled across borders and generations. But over the course of the 20th century, the Tekiyya was shut down, the unique religious traditions of the Iranian community fading away.

This completed a process of assimilation that had been under way for decades: in ritual, in religion, and in language. Those born in Egypt rarely grew up speaking fluent Persian, even if they could understand it. The rise of Egyptian nationalism in the early twentieth century, reinforced by state schooling, the dominance of Arabic in courts and administration, and the symbolic power of pan-Arab identity, hastened this linguistic and cultural absorption, leaving Persian as a fading marker of ancestry rather than a living tongue.

Mahmoud Fahmy, the grandson of Abdelhamid Kazrouni and current CEO & chairman of Kazrouni Carpets, shared a story his mother, Samiha, often told. At the Iranian Consulate in Cairo, a visiting minister from Tehran in the 1960s addressed the gathered community in Persian. It was a formal occasion, and the minister spoke with the kind of confidence that comes from assuming common ground; shared roots, shared language.

But as he continued, it became increasingly clear that the crowd was lost. The Persian didn’t quite land. Most of the audience, though of Iranian descent, no longer understood the language.

The moment exposed the soft erosion that comes with time and distance; not an abandonment of identity, but it’s reshaping. Families like the Kazrounis embodied this shift: Abdelhamid might switch to Persian with his brother or business partners when privacy was needed, but at home he spoke Arabic with his wife and children, who in turn were educated in English and French schools. Persian wasn’t rejected, it had simply faded, replaced by Arabic or French or English.

The legacy of Cairo’s Iranian community lives in fragments: a family name on a shop sign, a recipe passed down, a language barely spoken. The legacy of the Kazrounis is still felt in the prayer rugs of many mosques in Cairo, the whispered recipes of Zamalek homes, and the barely perceptible traces of Persian speech.

In my own family it surfaced in small habits, my grandmother setting the table with fork and spoon instead of fork and knife, or bidding us khodafez as she herself had once been taught. It persists not through grand monuments or official records but through memory itself. Perhaps this is the most meaningful tribute to Cairo’s Iranian community: their stories, quiet and often hidden, but woven into the city that made room for those who chose to call it home.