The following is a guest post by Hamed Noori, a multidisciplinary artist from Iran who currently lives and works in Cambridge, MA. His practice incorporates applied traditional arts, sculpture, photography, collage, and video. All carpets are from the private collection of Hamed Noori, and all images are courtesy of author.

***

I grew up in Mashhad, a city known for its religious life and long weaving tradition. My aunt, who lived with my grandmother, wove rugs at home professionally for many years. I remember watching her for hours as she tied knots, counted threads, and beat the weft into place. The sound of the loom and the rhythm of her work were part of my childhood.

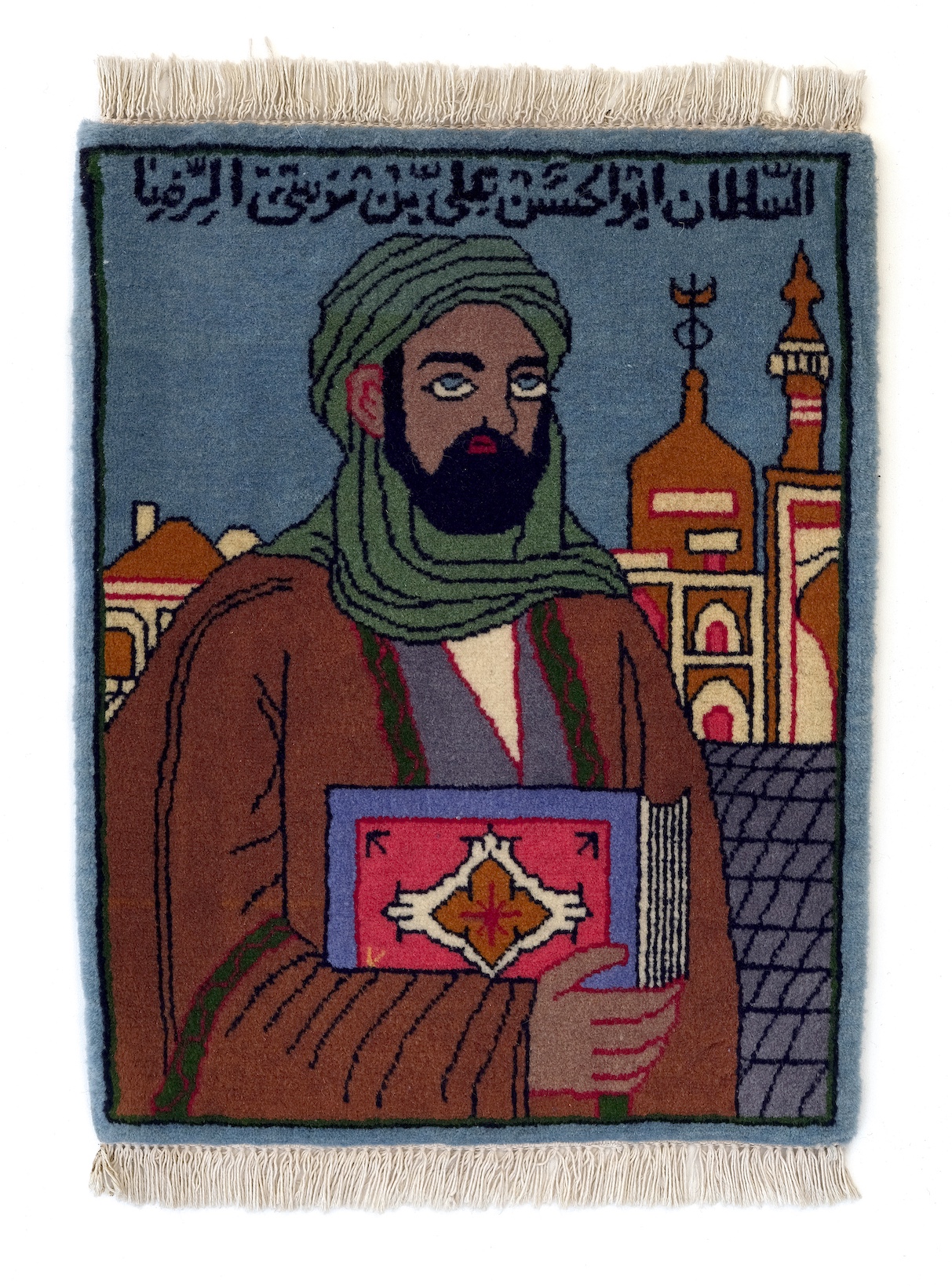

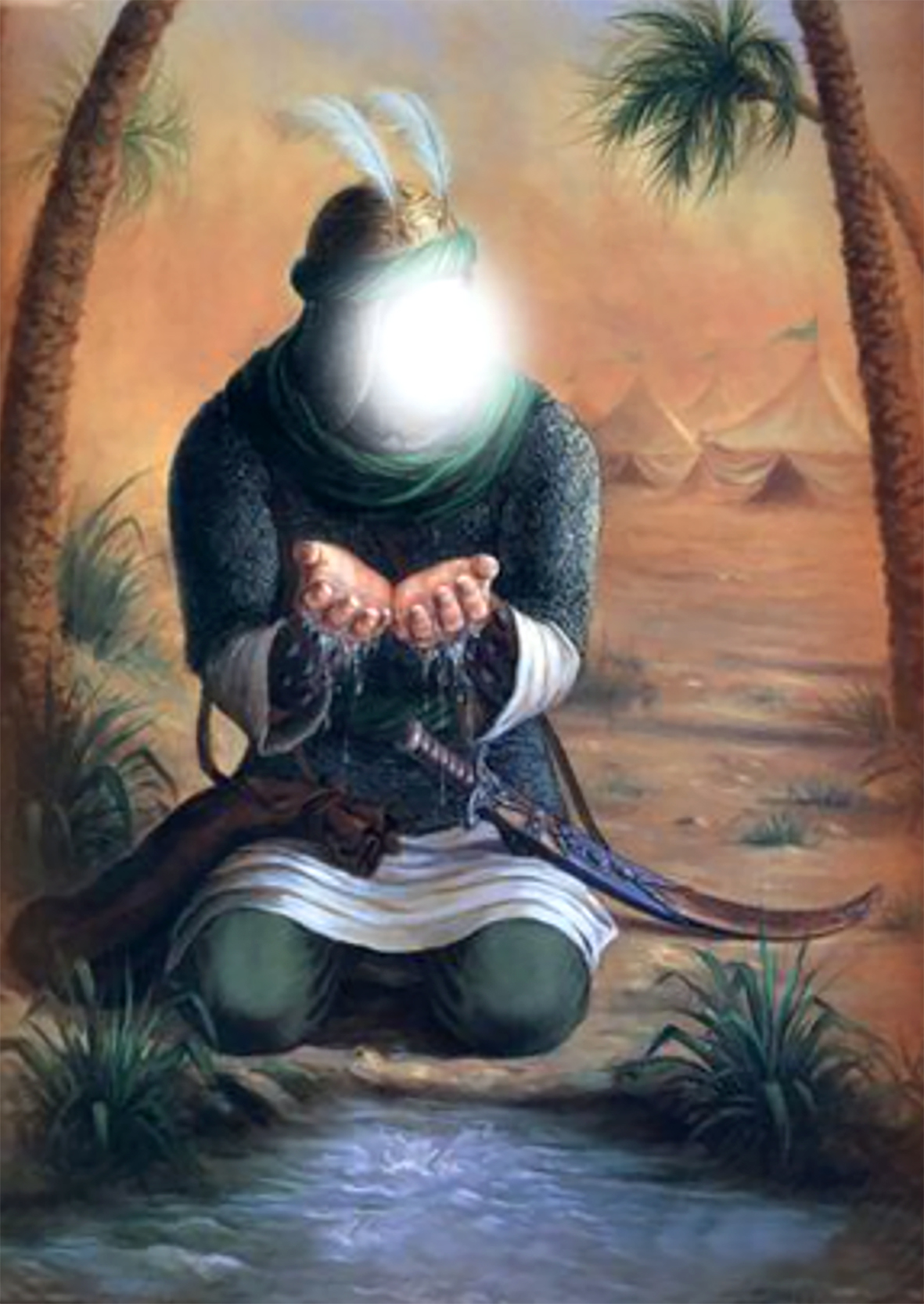

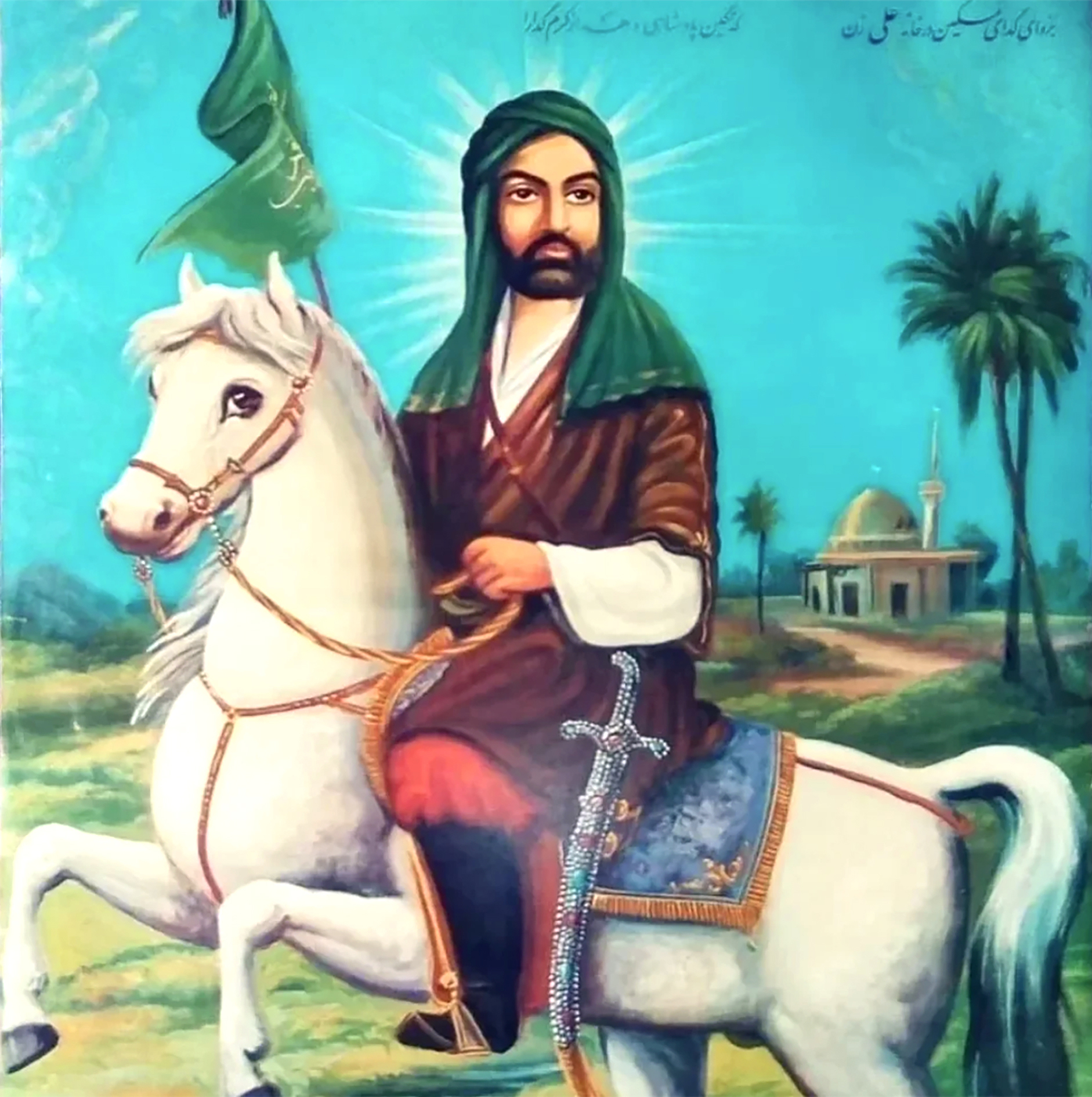

A memory that has stayed with me is of a small rug that hung in my grandmother’s house, a brightly colored carpet with the image of Imam Ali. It was displayed on the wall like a sacred presence, quietly watching over the room. That presence left a deep impression and later shaped my interest in the relationship between craft making, faith, and everyday life.

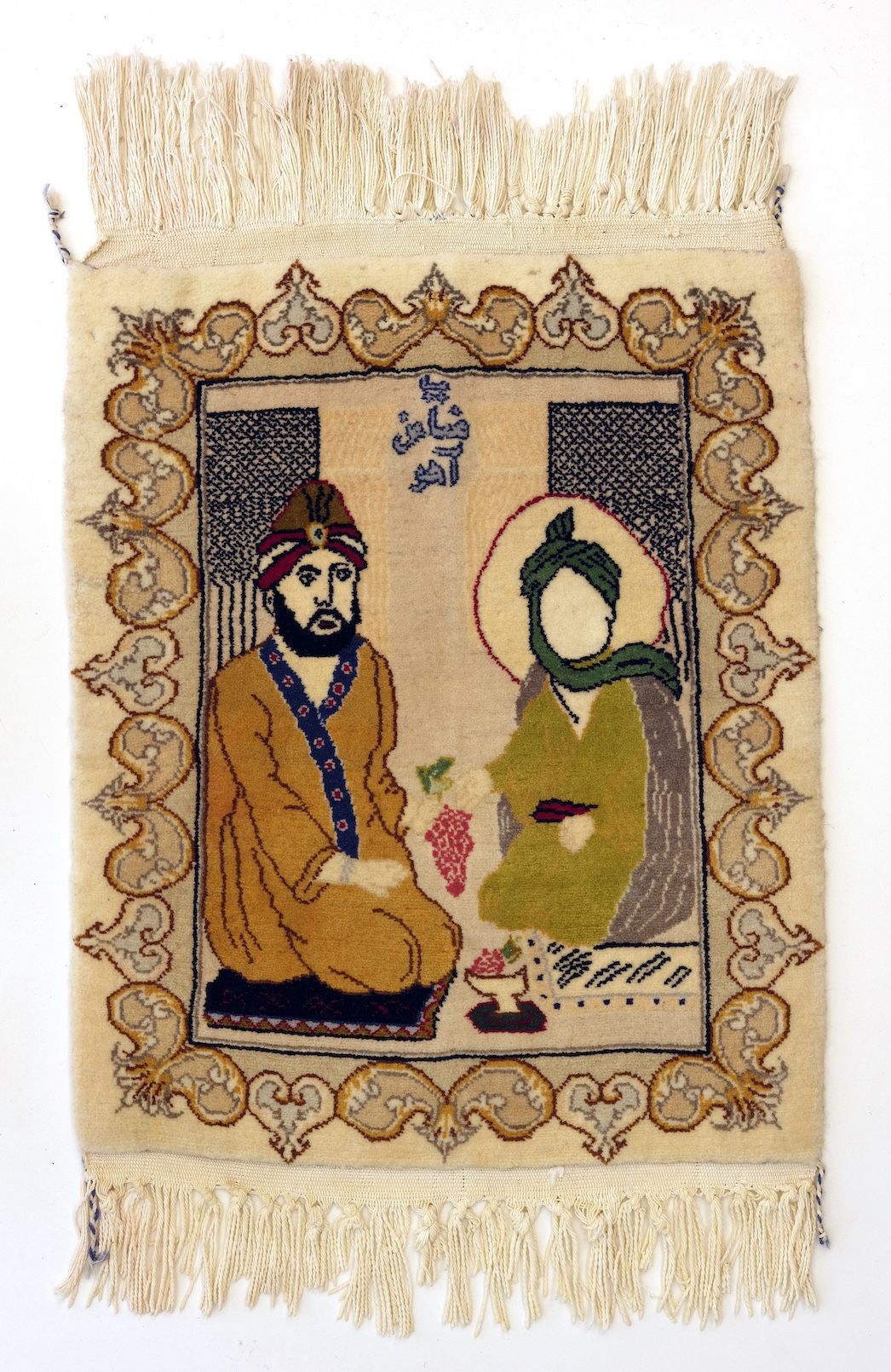

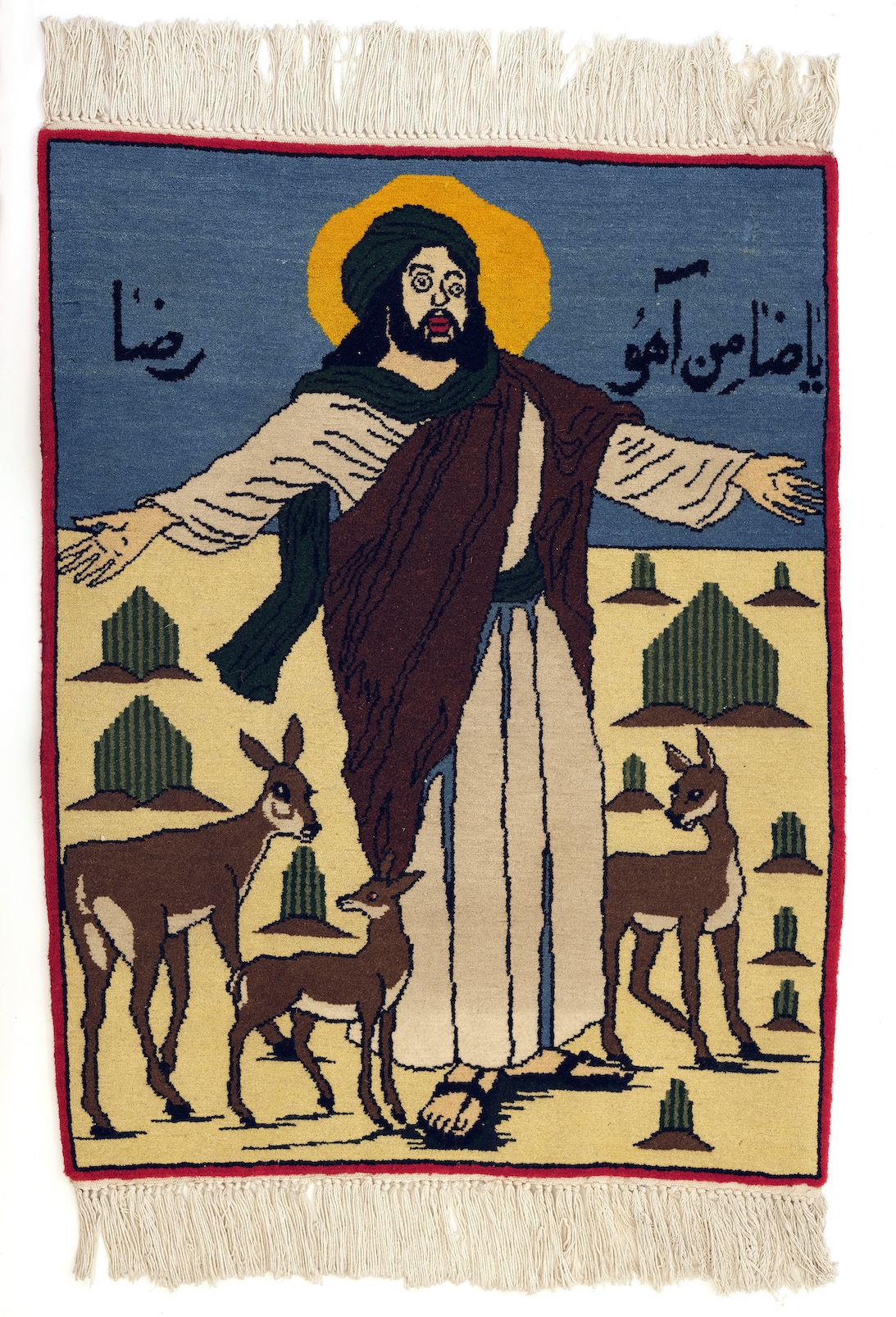

Years later, in the roofed bazaar of Nishapur, I found another rug that recalled that memory. Among the patterned carpets, one caught my attention with its rough, uneven texture. Yet it had the same presence, the image of a holy figure, rendered with bold lines and unexpected colors. That rug became the beginning of my search for similar works: a body of weaving that exists at the margins of Persian carpet traditions yet speaks deeply of creativity and devotion.

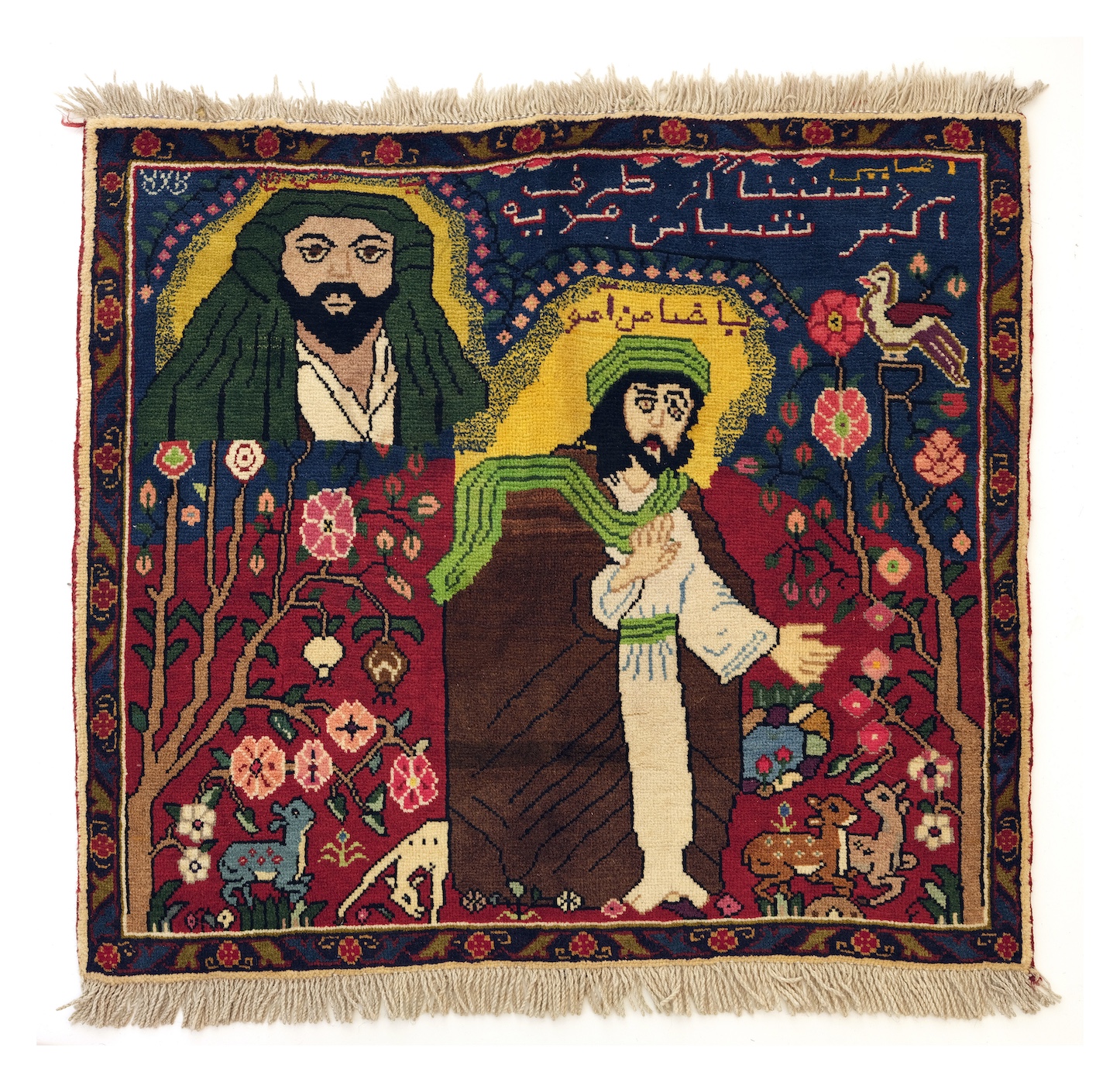

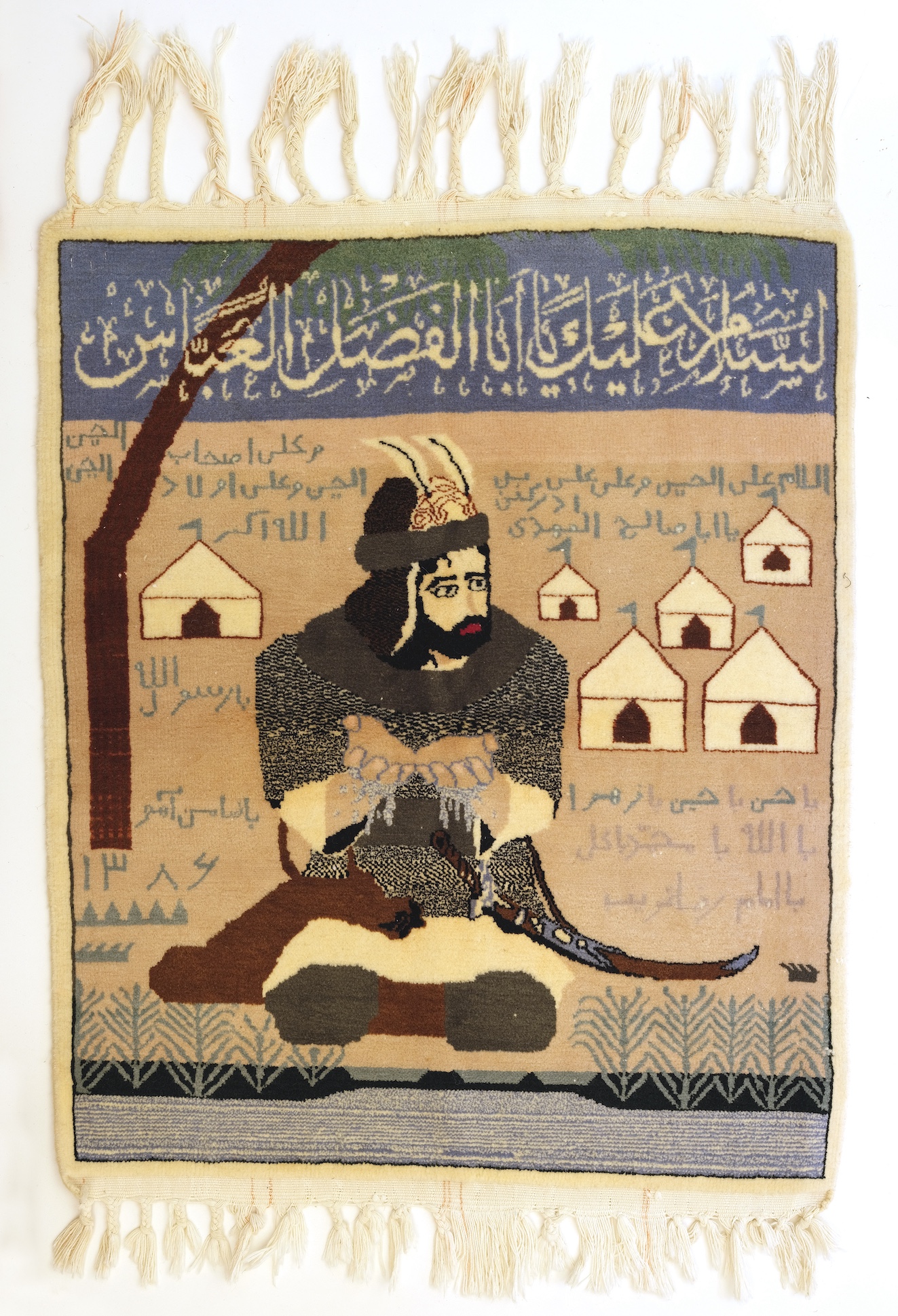

Over the past decade, my research has focused on handmade pictorial rugs produced in Khorasan. These works are very different from classical Persian carpets, which are known for their complex designs and technical perfection. They are smaller, more personal, and often show religious figures such as Imam Ali, Imam Reza, Moses, and Jesus.

The figures of Imams, saints, and prophets in these rugs are not portrayed realistically; the weavers prefer to keep the features minimal, reflecting the tradition of not showing holy figures too literally. What might appear as error is instead the freedom of an early gesture, shaped more by faith than by training.

Many of these pictorial rugs were woven by self-taught women at home, taking their first steps in weaving through portraits rather than patterns. As a result, they are often overlooked by collectors. Produced at home rather than in formal workshops, they were motivated more by belief and tradition than by the marketplace, even though some were once sold as religious souvenirs. Their making was rooted in domestic life, not in the structure or precision of commercial carpet production.

In earlier decades, pictorial rugs with holy figures were widely seen in homes, shops, and bazaars. Over time, however, their visibility in public settings declined. This shift may reflect changing tastes, but also the influence of religious authorities who have discouraged the display of shamayel in shrines, ceremonies, and communal spaces.

As public support faded, these rugs withdrew into private life, becoming personal keepsakes rather than public icons. Today, they are understood less as market items and more as devotional objects shaped by domestic spirituality.

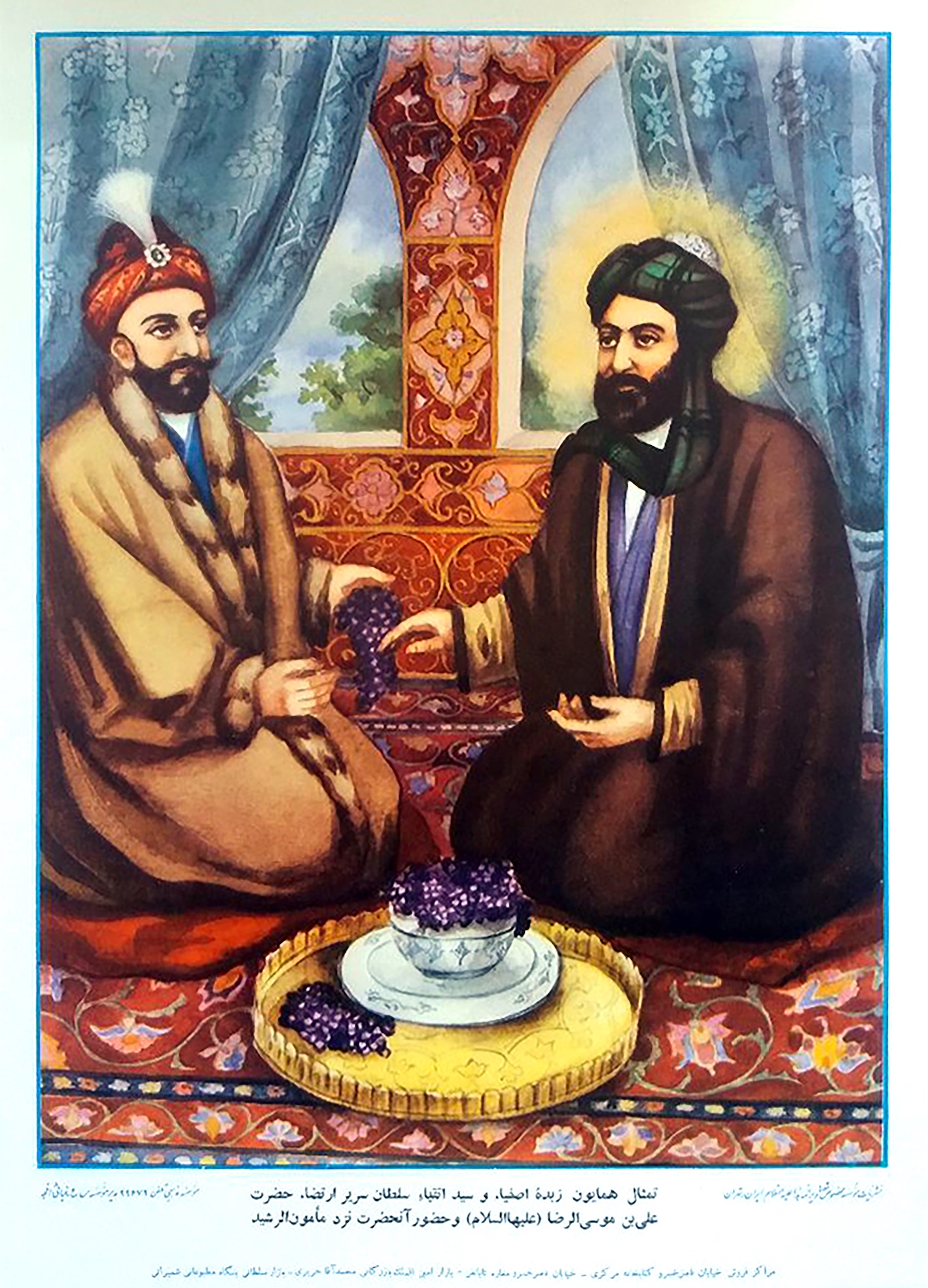

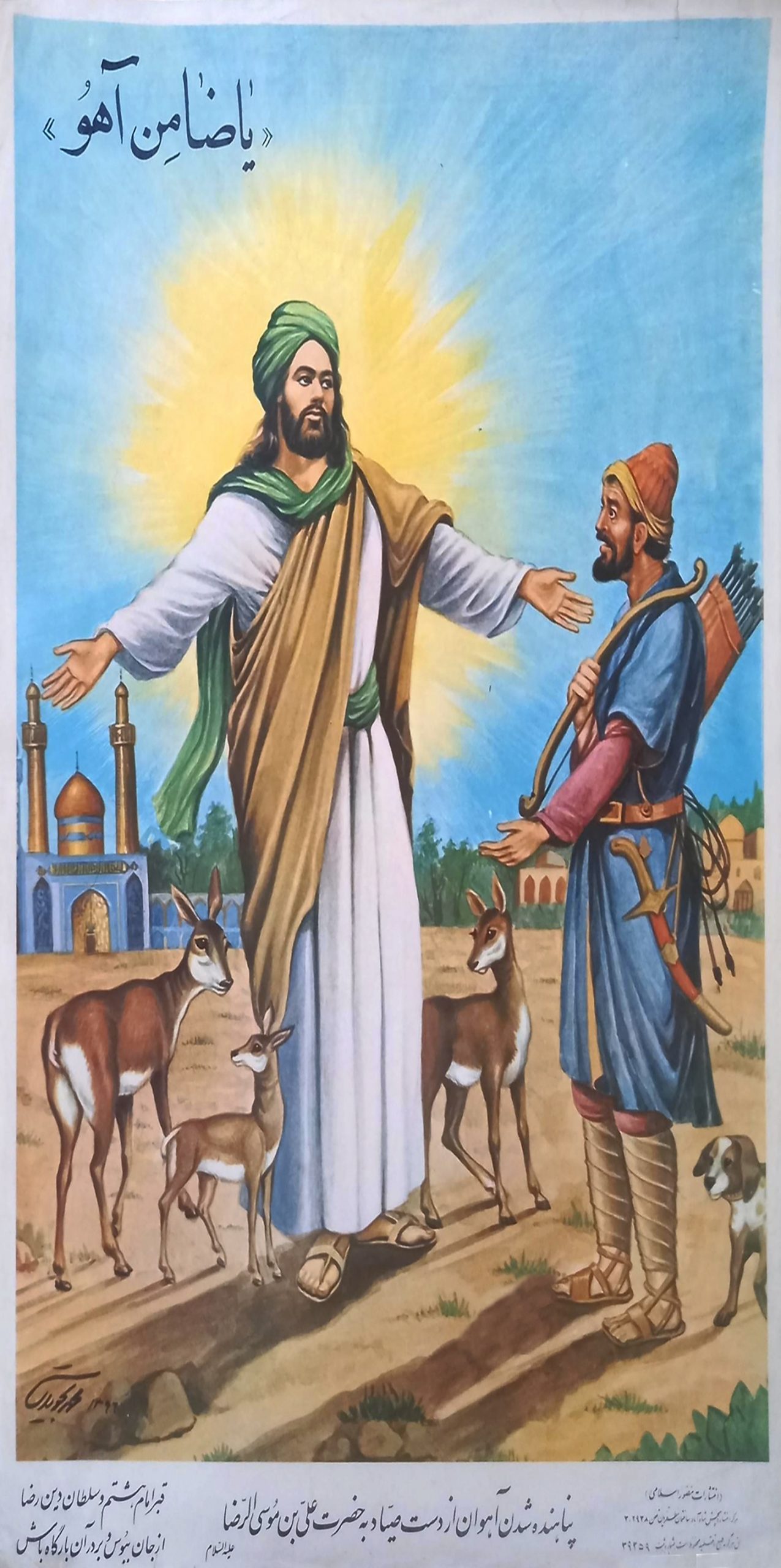

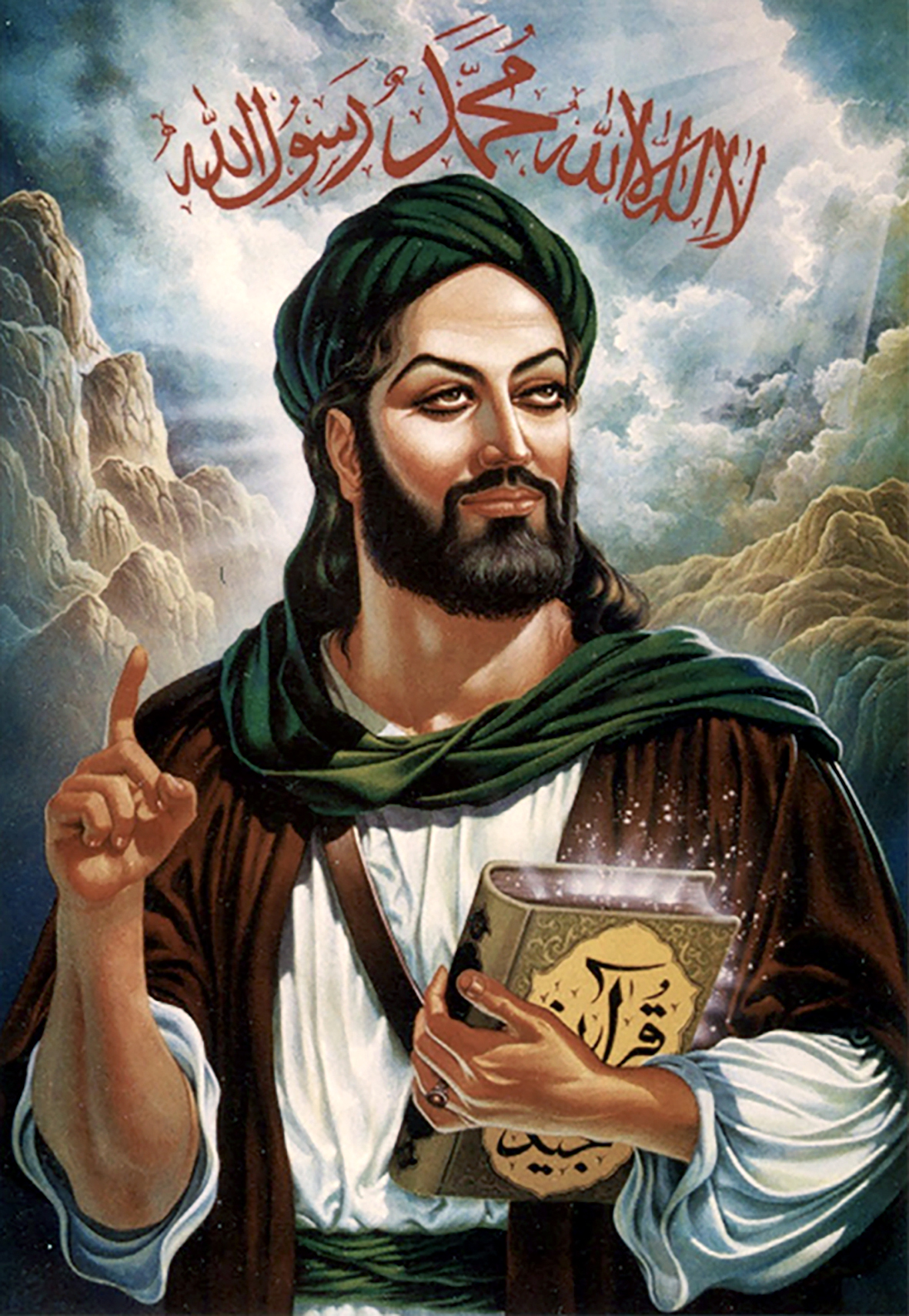

The tradition of shamayel, devotional image-making, first appeared in Iran during the Safavid period, when Shi‘ism became the state religion and sacred portraits of Imams and saints appeared in painting and shrine art.

Later, during the Qajar period, photography and lithographic printing transformed visual culture, making images common in books, prayer cards, and household objects. These developments also influenced textile design, including carpets. But the pictorial rugs I’ve studied were not copies of printed images.

Made in domestic spaces, often by women, they drew on imagination and personal faith rather than formal models. In this way, the rugs belong to the longer tradition of Iranian shamayel: devotional images shaped by ordinary hands as an act of belief. Each one brings together faith, memory, and material expression in a single woven form.

In Mashhad’s bazaars, I met traders, collectors, and weavers who continue to handle these rugs. In many shops, small pictorial pieces hang on the walls as symbols of protection or good fortune. When I asked shop owners to sell them, some refused, saying they were family gifts or had hung there for decades. Others agreed, explaining that if the buyer respected the image, the blessing would continue. These encounters showed how strongly these rugs remain tied to personal histories and everyday spiritual practices.

Mashhad has been one of Iran’s major weaving centers since the sixteenth century. During the Qajar period, its markets were filled with small prayer rugs and wall hangings sold to pilgrims visiting the shrine of Imam Reza. Nowadays, pilgrims often choose small printed images of Imam Reza as souvenirs.

Yet even today, buying a rug from Mashhad after a pilgrimage is still considered a blessing. The connection between weaving, faith, and commerce continues to shape the city’s cultural and economic landscape.

A carpet dealer near the shrine told me that the Imam Reza Shrine still receives thousands of donated rugs every year. Some are valuable and carefully preserved, while others are ordinary household pieces. Because the shrine cannot keep them all, it holds periodic auctions where traders and local buyers purchase the surplus.

This ongoing cycle—donation, circulation, and reuse, reveals how faith and economy are intertwined. A single rug can move from a home to a sacred site and back again, carrying meaning at every stage.

These pictorial rugs rarely appear in the mainstream histories of art that museums, archives, and academic institutions shape and preserve. Although absent from that formal narrative, they represent an important visual record of everyday creativity.

They show how image-making thrives outside professional studios and institutional frameworks. Each piece holds a blend of skill, imagination, and belief.

For me, these rugs are cultural documents, quiet conversations between belief and material. They show how spiritual and cultural values take form in the hands of ordinary makers, becoming visible, touchable, and lasting. Documenting and studying them is a way to understand how visual traditions continue beyond institutions through the creativity of everyday people.