The following was written by Parham Ghalamdar, a Manchester-based artist, writer, and filmmaker working at the edge of conflict visibility, censorship, and machine-mediated images. He is the maker of The Sight is a Wound (2025) and Siahkal 2.0: An A.I. Resurrected Discourse on Marxism & Islam (2025). A version of this essay previously appeared in Shadowbanned magazine.

***

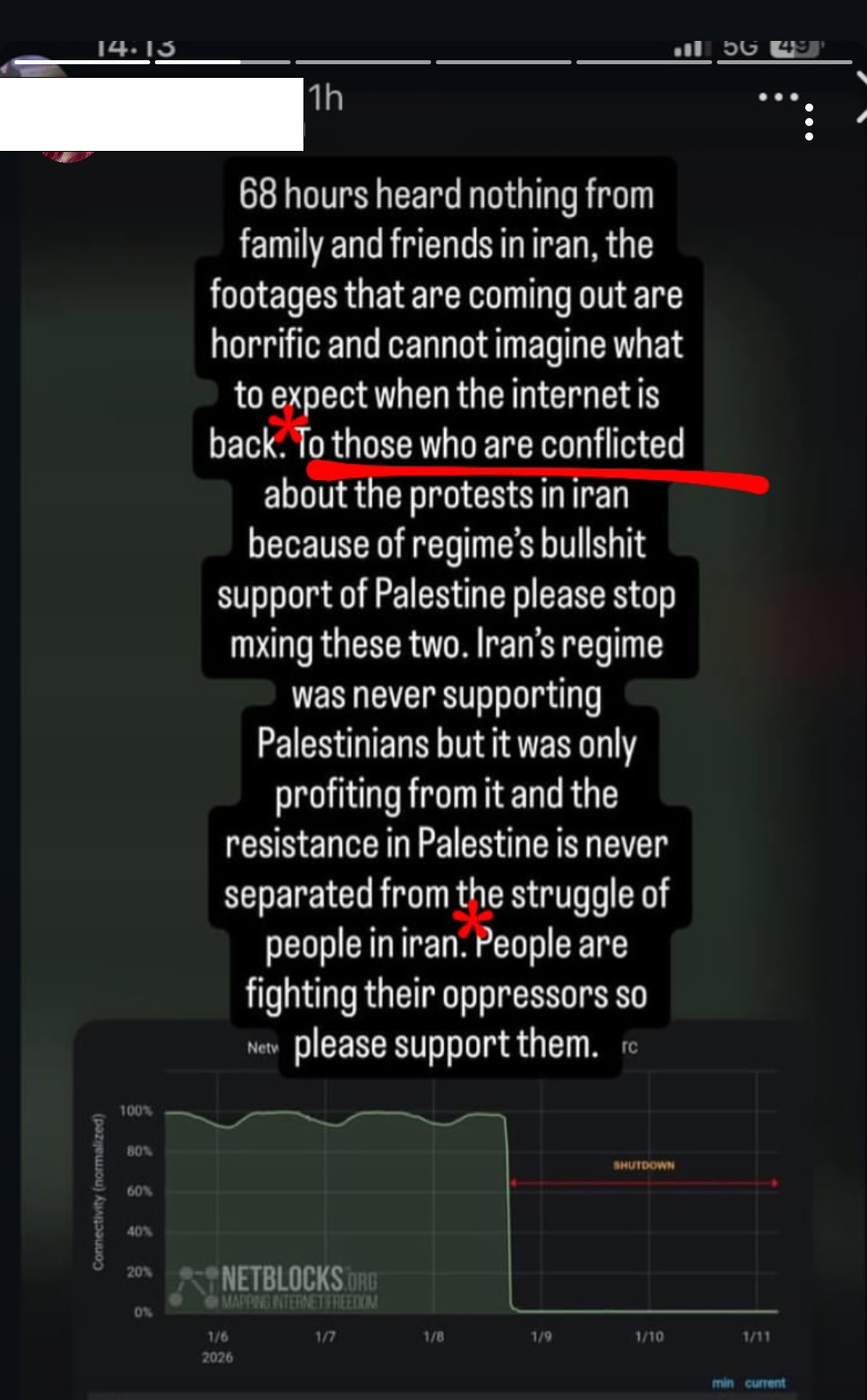

In early January 2026, protests spread across Iran. Security forces cracked down and imposed a near-total internet blackout on the country. People inside and outside Iran were left trying to understand events through fragments: expensive, broken roaming calls, delayed messages delivered via VPN and proxies, and the rare leaked clip. Some footage moved via Starlink access unstable under interference and GPS jamming, arriving in bursts, half-seen and hard to verify.

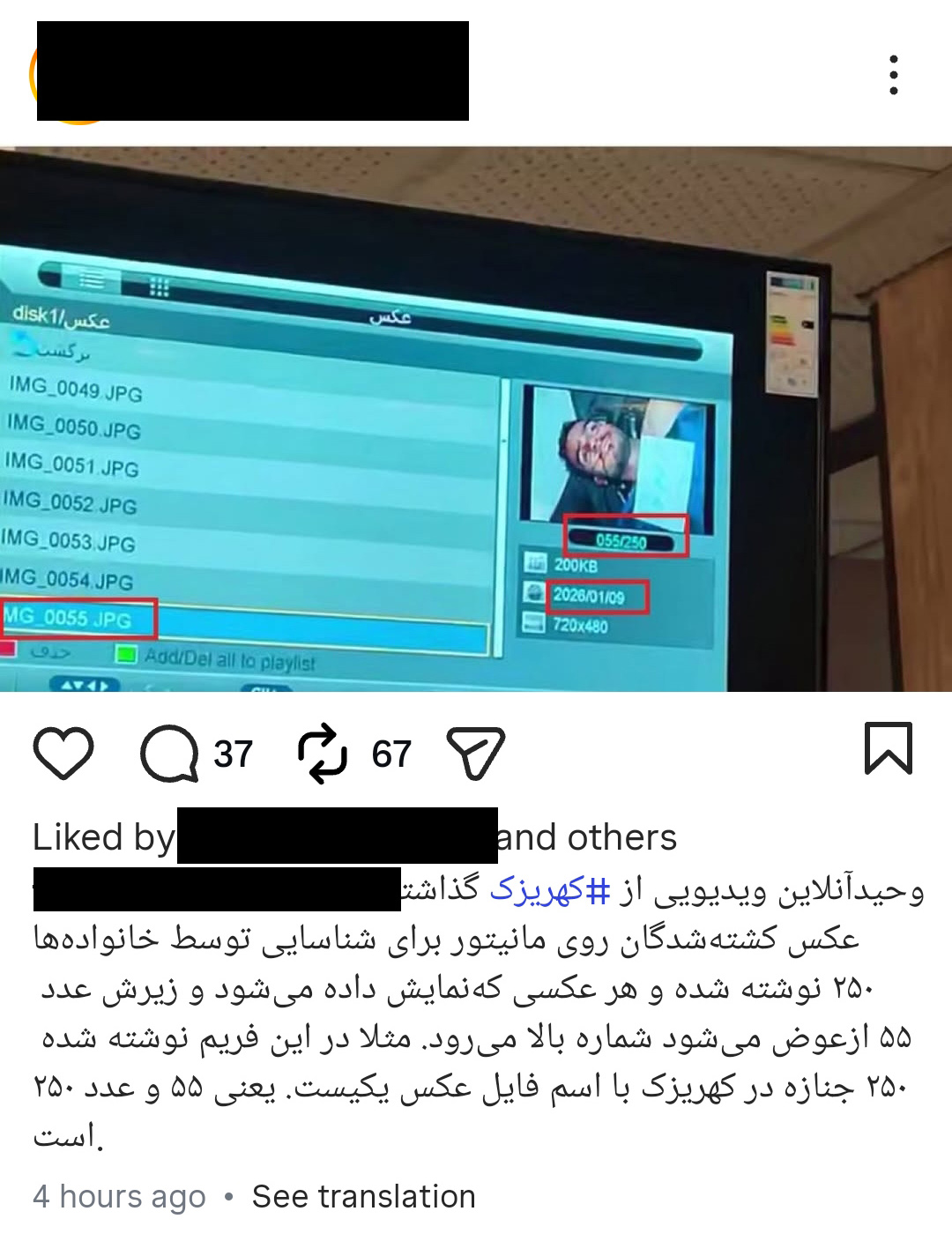

Video filmed at the Kahrizak forensic centre in Tehran shows families gathered around a monitor, scrolling through low-resolution images of the dead, searching for a face they recognize. Forensic Architecture assembled a short briefing from morgue footage and witness testimony tracing how Kahrizak images travelled during the shutdown.

This is part of a wider pattern of our time: mass death paired with blocked visibility, where the struggle is not only to survive violence but to make it legible at all. Blacking out communications and jamming signals become tools of power worldwide, from Iran to Gaza and beyond. But blackouts do not erase events, they shape what can be proven, mourned, and acted upon.

I wrote this theory-fiction essay during Iran’s communications blackout to understand what happens when mourning is forced through an interface and death is indexed.

***

A protocol note from the digital blackout in Iran (8th of January 2026 – and counting)

The first thing you learn when the network goes dark is that darkness is not the absence of images. It is the rationing of images.

Blackout does not mean the screen is empty. It means the screen has moved. It has retreated behind walls, behind checkpoints, behind “authorized access.” It means the image has been reassigned from public circulation to internal administration. You do not stop seeing. You lose the right to see.

Somewhere in Tehran, a monitor stays on.

A video circulates with a caption that reads like a field report, like a warning label, like a plea.

Families gathered at the Kahrizak forensic centre. Searching for bodies. Scores killed. Severe crackdown. Near-total internet blackout. The few videos posted are uploaded through rare satellite access, still affected by GPS jamming.

If that caption is to be believed, the event has already been formatted. Not into a story, but into a logistics chain.

Families. Facility. Bodies. Numbers. Blackout. Satellite. Jamming.

A sequence of nouns arranged like a corridor.

And then the video itself. Not a cinematic image. A screen filmed by another screen. An interface captured in panic, through the wobble of someone trying to keep their hands steady. A list of files. Thumbnails. A face in a rectangle. Metadata.

Date stamp. Resolution. The camera does not show the body directly, it shows the bureaucracy of the body.

This is how power likes to appear when it thinks no one is watching. Not as an officer, not as a speech, not as a slogan. As a user interface.

1. The face as a unit of administration

In ordinary times, a face is a social object. It attaches to a name. It carries a life. It triggers memory and feeling. It is messy and excessive. It refuses to stay still.

In institutional time, the face is not a person. The face is a handle.

A handle is something you grab in order to move something else.

In the forensic interface, the face becomes a handle for routing the dead through procedures. The face is a key for matching. It is an index for retrieval. It is a shortcut that allows the system to avoid the harder work of naming, acknowledging, accounting.

The list of files is a list of handles. Each file is a body without a body, a proof without a public, a portrait that does not want to be a portrait.

A family stands behind the screen and waits for the machine to cooperate.

The machine is not cruel in the way a person is cruel. The machine is cruel in the way a form is cruel. It asks you to compress your grief into yes or no. Match or no match. Proceed or do not proceed.

The grief has to become legible. It has to submit to the interface.

The interface does not just display faces, it produces the conditions under which a face can be recognized at all. It decides what counts as enough clarity. It decides how recognition is confirmed. It decides what happens after recognition. It makes recognition actionable.

And in this actionability, the face becomes political, not as a metaphor, as a mechanism.

2. Visibility as governance

The caption says “near-total internet blackout.” Even if you treat that as a general description rather than a precise measurement, the logic holds: when connectivity collapses, visibility becomes a controlled substance.

People often talk about the internet as a space of expression. Under blackout, it reveals itself as infrastructure, and infrastructure reveals its true function: to decide what flows, where, and for whom.

A blackout is not just silence. It is a redistribution of speech rights.

The state does not need to erase every image. It needs to control which images can form a public. It needs to prevent a shared timeline from consolidating. It needs to keep events local, fragmented, deniable. It needs to turn reality into isolated incidents.

The blackout is a technique for manufacturing uncertainty.

When the network is cut, witnesses cannot synchronize. Videos cannot corroborate one another. Names cannot travel. Patterns cannot be established. The dead cannot easily become countable in public, even as they become countable on internal screens.

This is the split that defines the scene at Kahrizak.

Inside, the system counts. Outside, the world guesses.

Inside, there is a database. Outside, there is rumor.

Inside, the face is a record. Outside, the face is a missing story.

The blackout does not stop documentation. It relocates it. It moves it from the street to the archive. From the public feed to the forensic folder. From social circulation to administrative storage.

It turns the country into a sealed container with an internal camera.

3. The scroll as a ritual of modern mourning

The video shows a particular gesture. Someone scrolls.

This is the same gesture people use to browse photos of friends, to watch jokes, to follow news, to doomscroll. The hand motion is familiar. That familiarity is the horror. The body does not know it has entered a different moral universe. It performs the same movement, but now the stakes are identification of the dead.

Scrolling is how the interface trains you to accept infinity. There is always another item. Another clip. Another face. Another update.

At Kahrizak, scrolling becomes a ritual of forced recognition. It asks families to do the work the state will not do publicly. It asks them to translate disappearance into proof. It asks them to carry the burden of naming inside a system built to avoid naming.

The file list is a mass grave with a cursor.

The thumbnail is a coffin lid that opens and closes at the speed of a fingertip.

The families are made into users, and their grief is made into a query.

You can feel the cruelty of the interface design even in its banality. Not because the designers intended cruelty, but because the interface is optimized for throughput. It is optimized for speed, for consistency, for processing. It treats faces as items and people as operators.

In the logic of the system, the family’s role is not to mourn. It is to confirm.

4. The face as evidence and the collapse of the private

Under blackout, a new kind of portrait circulates. Not the portrait you choose. The portrait that escapes.

The uploaded video is not clean. It is shaky. It is partial. It carries the marks of risk. It is filmed quickly, as if the act of filming itself is a crime.

This is not the aesthetics of self-expression. This is the aesthetics of extraction under threat.

The face appears under fluorescent light, in low resolution, compressed by the limitations of the channel. The face is no longer a self. It is an evidentiary object.

In open networks, people often curate their faces for recognition. They style themselves into legibility. They learn the angles, the lighting, the micro-expressions that read well. They participate in the quiet labour of being interpretable.

Under crackdown, the same interpretability becomes a vulnerability. The same face that can be recognized by friends can be recognized by systems that do not love you.

This is why the blackout matters. It controls not just what is said, but what can be safely seen.

Yet the Kahrizak video shows the counter-truth: even when the network is suppressed, the face remains extractable. If anything, it becomes more extractable, because it is now a piece of evidence that can be weaponized, contested, denied, or used to coerce silence.

The private face becomes public in the most violent way, by being stolen into an archive of death.

And the public network is forced to watch through tiny punctures, through rare satellite links, through leak channels. The public sees only enough to be horrified, not enough to assemble full accountability.

5. Starlink as contraband sky

The caption mentions rare satellite access, and GPS jamming.

Whatever the exact technical details in this specific case, the symbolism is clean. The sky becomes a smuggling route.

When the ground network is choked, the signal tries to go above the state. It tries to exit the territory vertically.

But the state responds by attacking the conditions of navigation itself. GPS jamming does not just interfere with location, it interferes with the possibility of stable orientation. It turns the air into a fog of coordinates. It makes the outside unreliable.

That is the deeper logic of blackout. It is not only about blocking content, it is about destabilizing the concept of an outside.

Even satellites, even sky, even the fantasy of a neutral orbit, becomes contested.

The leak arrives, but it arrives damaged. It arrives stuttering. It arrives as a fragment. It arrives with just enough clarity to confirm horror, and just enough distortion to keep doubt alive.

This is a new genre of testimony: the jammed confession.

A video that says, “This happened,” while the channel itself says, “You might not be able to prove it.”

The state does not need to stop every packet. It needs to corrupt the reliability of packets. It needs to keep the public trapped between certainty and uncertainty, outrage and exhaustion.

6. How a face becomes a number

The interface shows metadata. There is a file name pattern. There is a counter. There is a date.

A face, in this system, is not primarily attached to a name. It is attached to a sequence.

Once you are sequenced, you are governable.

Numbers are clean. Numbers travel well inside institutions. Numbers can be compared, aggregated, audited. Numbers can be cited without mourning. Numbers can become “security incidents.”

This is why regimes love numbers and hate names.

Names create obligations. Names create stories. Names create funerals. Names create anniversaries. Names create martyrs. Names create witnesses.

Numbers create summaries.

A file named IMG_0055.JPG does not demand justice. It demands storage.

The family stands there and tries to reverse the conversion. They try to take the number and return it to a name. They try to pull the face back into the social world where it belongs.

This reversal is not guaranteed. The interface is not built for it.

The interface is built to make the dead manageable.

And this is where the politics of the face becomes unavoidable. The face is the last remaining bridge between a person and a record. It is the surface where the family can still say, “This is not an item. This is ours.”

Recognition becomes a struggle over the meaning of a rectangle.

7. The morgue as platform

It is tempting to think of platforms as online spaces and morgues as physical places. The video collapses that distinction.

A platform is any system that standardizes how humans appear so that they can be processed.

A platform is any architecture that turns life into inputs and outputs.

The Kahrizak interface is a platform. It has formats. It has templates. It has defaults. It has a logic of what counts as a valid entry.

It takes the most intimate thing, a face, and forces it to behave like a file.

What makes this unbearable is not only the presence of death, it is the familiarity of the interface logic. Many of us live inside file lists. We drag and drop. We rename. We sort by date. We delete. We scroll.

Now imagine that same interface logic applied to bodies.

This is the truth the blackout tries to hide. Not only that people were killed, but that their deaths were absorbed into a procedure that looks like everything else. A death becomes one more thing the system can “handle.”

The families are not only mourning, they are confronting the administrative digestion of their loved ones.

They are watching their dead become compatible with folders.

8. The leak as a new kind of funeral

In a functioning public sphere, mourning has rituals. It has gatherings, processions, prayers, speeches, graves, public memory. Even when states attempt to suppress mourning, people invent ways to mourn together.

Under blackout, the leak becomes a substitute ritual.

A leaked video is passed from phone to phone like contraband incense. People watch and cover their mouths. People watch and message each other, “Have you seen this?” People watch and try to verify. People watch and feel the old helplessness: we can see, but can we act?

The leak produces a public, but a fragile public. A public assembled from fragments, always at risk of collapsing into disbelief or despair.

And the leak does something else. It forces the state’s internal interface into the public imagination.

It reveals how the regime sees you when it does not need your consent.

Not as citizens. Not as believers. Not as enemies even.

As entries.

As cases.

As files.

This is why the Kahrizak video hits so hard. It is not only showing grief. It is showing the administrative substrate of grief. It is showing the technical layer of mourning that is usually hidden.

The leak is a funeral for the idea that the state does not know what it is doing.

The interface looks practiced.

9. A closing note, written as a constraint

There is a sentence people repeat in different forms: “the face is political.”

Most of the time it sounds like critique. Here it sounds like a description of a workflow.

At Kahrizak, politics is not a speech. It is a queue.

Politics is a person standing in front of a monitor, trying to identify the unidentifiable, inside a system designed to keep accountability out of reach.

Politics is a blackout that does not erase images, it hoards them.

Politics is a satellite packet that escapes the country like breath escaping a sealed room, and arrives on the other side bruised by interference.

Politics is the cruelty of low resolution, not because low resolution is ugly, but because low resolution is plausible deniability. Low resolution is how violence survives into the realm of “maybe.”

And yet the video exists. The fragment exists. The face exists on the screen, refusing to be only a file.

This is the contradiction that defines the moment.

The apparatus wants faces to be legible enough to process, but not visible enough to mobilize.

The families want faces to be visible enough to mourn, but not so exposed that the dead are reduced to content.

The leak forces the face into a third state.

Not private. Not fully public.

A hostage image.

An image that carries grief and proof at the same time, and is therefore always at risk of being exploited by everyone, including those who claim to care.

A face on a forensic screen is not merely a tragedy. It is a diagram of how contemporary power formats life and death when it can no longer afford open visibility.

In blackout conditions, the regime does not only kill bodies.

It tries to kill the ability to assemble a shared picture of what happened.

And the families, in front of the monitor, refuse that second killing.

They stand there, and they look, and they try to return the face to the world.

Not as infrastructure.

Not as an item.

As a person.

As a name.

As something that cannot be scrolled past.