By January 1990, the Soviet Union was falling apart at the seams. Nowhere was this more obvious than the hastily-stitched together Caucasus, where decades of delicately-balanced workers’ solidarity was being torn apart by ethnic chauvinism. Baku, the Caspian port famed for its oil, caviar, and ethnic harmony became famous for a Soviet army invasion as well.

The final toll was over a hundred Baku residents dead, an exacerbation of the Nagorno-Karabakh War between Armenians and Azeris, and a substantial bucketful of dirt thrown into the USSR’s grave. The millennia-old Armenian community of Baku fled en masse, leaving their homes and their culture for points north, west, and south. It was hardly just the Baku Armenians who suffered, however, and Thomas de Waal’s research states that roughly 750,000 Armenians and Azerbaijanis became refugees. The promise of a post-Soviet wonderland was impossible to fulfill with one-tenth of the region’s population displaced, and many Armenian refugees fled for America. One of these refugees was a three-year-old future soccer superstar.Yura Movsisyan – a stateless infant – came stateside along with his family.

The Movsisyans could never go home again. Baku has been rebuilt in the past 20 years thanks to its third wave of oil and a riptide of construction,but it is now the capital of a newly-nationalistic Azerbaijan that remains in a state of de-facto war with the Republic of Armenia that originally sheltered the Movsisyans.

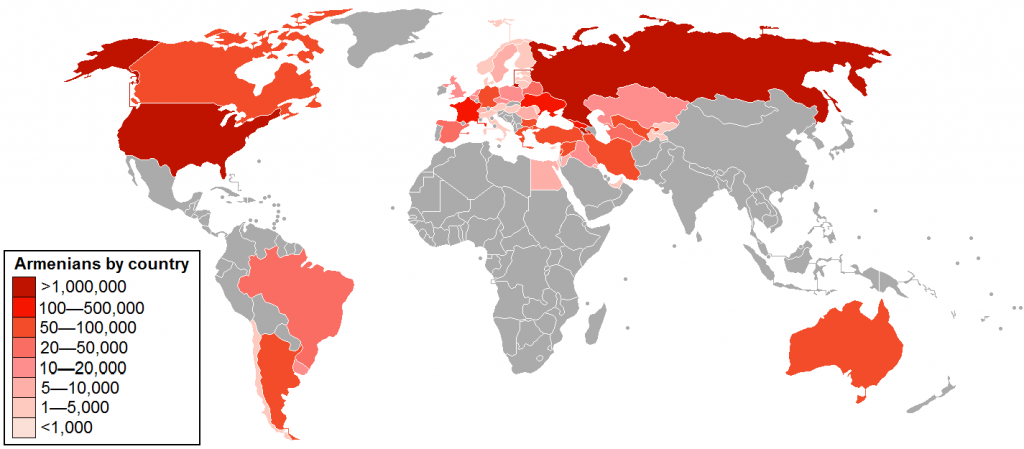

Los Angeles, however, is home to the largest Armenian population outside of the former USSR. There is perhaps a difference between Los Angeles proper and the Los Anzheles of Glendale, Pasadena, and Montebello. In the former you’ll find blonde surfers, taco trucks, and in the latter you’ll find those too, but interspersed between carpet shops, music stores promoting the famous Zildjian cymbals, and bakeries chock-full of choreg, matnakash, and the smells those loaves disperse. It’s America, because every cultural conclave in Los Angeles is America. On the other hand, if the mountains of Ararat and the churches of Jerusalem symbolize the lost soul of the Armenian Diaspora, the heart remains in Los Anzheles. It’s an America that a refugee immigrant family can immediately find their bearings in. Especially if the youngest son of that family has a preternatural affinity for soccer.

AMERICA, ARMENIA, AND SOCCER

Yura is not the first Armenian to make his mark on American soccer. Adranik Eskandarian got his start at Ararat Tehran – the premier team of the Armenian community in Iran – before moving on to Iranian giants Taj (now Esteghlal). Adranik was a petal on that blossom of the Iranian national team that won two Asian Cups and went to the World Cup for the first time in the nation’s history in 1978.

Eskandarian moved to New York after that World Cup to become a member of the legendary New York Cosmos. Andranik never played internationally (if the Cosmos don’t count) after 1978, and he became a bit of a symbol of the Armenian diaspora in doing so: barred from the post-Revolution Iranian national team, ineligible for the Americans, and unable to play for a non-existent Armenian state, Adranik became a man whose talents were caught between boundaries.

The Armenian community rarely moves as a unit. Rent by at least twelve dialects and from a land trisected by three empires (Russian, Ottoman, and Persian), every family has its own unique history that can perhaps be remembered a few generations back and tied into the larger story. Soccer, along with wrestling and weightlifting, is one of the few common causes the community can rally around besides church. Sport gives people the excuse to shed regional misgivings for a united cause. “The Armenian Diaspora has historically excelled at finding ways to come together,” says Joe Hanovnikian, a medical student at the University of Illinois and a former member of one of the many clubs around the United States that call themselves Ararat F.C. “Sporting events are a way to temporarily demolish the national borders that have separated ungerner (Armenian for “friends”) from one another.”

The Armenian Diaspora revolves around the language and the church, the “1A and 1B” of Armenian life, according to Baku-born Seattle resident Max Nazaryan. Shared Armenian-American heroes ought to come after God and tongue, but there are strangely few in America. Yura Movsisyan speaks a broad and clear Armenian (Hayeren) and seems genuinely frustrated when asked to choose his favorite Armenian singer in an interview (he eventually splits between Armen Hovannesiyan and Spitaksi Hayko). He is married and has two children at age 25. What’s more, he has done the impossible and outgrown America. After five years in MLS, Yura had his contract bought out by Danish power Randers FC. Two years later, he would be back among his own people. Not in Los Angeles, though, and not in the young Republic of Armenia, either. Yura was off to Russia. The largest Armenian population outside of the Republic is in Krasnodar, where Yura moved to in 2010. Halfway through the 2012-2013 Russian Premier League season he moved to one of the traditional giants of the league, Spartak Moscow.

However, following Yura’s burgeoning worldwide fame, the jerseys with MOVSISYAN on the back that dot Sunday school playgrounds aren’t in Real Salt Lake or Spartak colors. They are rather the red-blue-apricot of Armenia. Armenia have never seen much success in international competition, but they are counting on Yura’s generation to lead them there.

Yura proudly calls Los Angeles (to be exact, his parents’ home in Pasadena) home, but when asked if he was going to play for the United States or Armenia, he reiterated that “I am Armenian, I was born in Azerbaijan, Baku (the capital), but I am Armenian. That’s what I want people to know.” He called America the “dream life,” and the biggest chance he got in the land of opportunity was to be at home with his people and to make them proud. Nazaryan explains that “playing for the Republic’s national squad is sort of the end all of an Armenian sports hero and elevating [the sport] to a quality of play the young country has never seen is kind of a unique achievement.” When Yura tells his soccer clinic that “I had the choice to play for Armenia or America, and I decided to play for Armenia and go back to my country,” the applause is deafening.

ARMENIAN IDENTITY

Due to the linguistic peculiarities, the history dominated by kings of other empires, and the Diaspora community spread through six continents, it is tough to get any two Armenians to agree on dinner, let alone on a hero. But Yura is something different. He’s a physical specimen – a mountain that flies – in an age when tonight’s Krasnodar-Kuban match can be viewed this morning in Boston. He’s a clever jokester with a bilingual mouth as fast as his feet in an era when English dominates the internet and Hayeren dominates a patriot’s tongue. He’s a father of two who calls his parents’ Pasadena house “home” in a year, like all years, when soccer players’ antics dominate tabloid headlines.

“When an Armenian athlete like Yura reaches his goals, we as a people reach our goals,” muses a proud Los Anzheleno at Yura’s winter Pasadena soccer camp. “We come here to show him that we value his work.” This communal pride is not just for Southern Californians. Max Nazaryan, who as a proud Seattlite has only a sneer for most Californians, states flatly that “we have produced him,” that Yura is a product of all Armenians everywhere. For if Ararat is still the geographic symbol of Armenian loss, Yura’s birthplace of Baku is the symbol of a strained cosmopolitanism. Nazaryan explains, as fellow Baku-born, that “Yura could never tell a fellow Armenian he is from Baku, even if he believed it, for political reasons.” Anna Astvatsurian, a Baku-born Armenian writer, goes even further, explaining that “Armenians of Baku…were too traumatized to revisit it themselves. They are still traumatized. They don’t talk about it at dinner tables. They don’t tell their children about it. But it is always there on their minds because they haven’t had an opportunity to heal.”

Baku Armenianness is only the latest of the widespread web of the Armenian community to make a home in Los Anzheles. Armenians have been coming to the United States for as long as there has been a United States. Even when the US attempted to shutter its doors to “Asiatics” in the 20th century, four Armenians petitioned successfully to be considered “White” despite living in the Persian and Ottoman empires in the 1909 case of In re: Halladjian. This rare instance of adjudicated whiteness allowed for a community to grow on America’s East Coast. It was not until the Lebanese Civil War and the Iranian Revolution – coinciding with an economic boom in southern California – that Los Anzheles came to be. And there a different sort of Armenia, one that crosses chronology and geography, has been created. The Los Anzhelenos welcomed Soviet refugees such as Yura in the 1990s empathizing with their loss and optimistic in creating something better. Yura Movsisyan is a very real, uncluttered, symbol of what a 21st century Armenianness might be.

After all, Yura is a folk hero not just for his singularity, but also his relatability. He is both the boy next door and Horatio Alger. Astvatsurian is optimistic about her kind, stating that “We adapt anywhere we go and succeed at pretty much anything we set our minds to, because we grew up living with a constant expectation that you work a little harder, to prove yourself a little more because in the end, you are Armenian or a Bakvetsi [someone from Baku], or a refugee. We survived and endured so much, together and alone.” Yura has survived and even thrived, both alone and among his people. He has lived in three of the biggest Armenian communities: Soviet Baku, 21st Century Los Angeles, and the Russian Federation’s glitzy new Krasnodar. Everyone seems to know somebody who knows somebody who knows him, and a few may even be telling the truth.

5 comments

Very interesting article!

I’m glad Montebello was mentioned! Montebello is unique because it’s one of the earliest sites of organized Armenian settlement in L.A.–Armenians from the Soviet Union established a community there after World War II. Within the community, they are referred to as “Rusahay” (meaning Russian Armenian) due to their emigration from Soviet Russia, even though they no longer speak much Russian or even Armenian and are probably among the most assimilated (and successful) of L.A.’s Armenians. Many of them have also left Montebello for more affluent suburbs.

I knew Yura played at Pasadena College but I always thought he was Glendale-bred. Interesting–Pasadena actually has a smaller proportion of Armenian immigrants from the former Soviet Union (in relation to Armenian immigrants from Lebanon, Iran, Syria, Turkey, etc.) compared to the Glendale/Burbank/La Crescenta area.

There was another Armenian MLS player and he played for L.A. Galaxy: Harut Karapetyan, who is still the recordholder for the fastest hat-trick in MLS history.