The first part of the following piece is written by Ajam Co-Editor-in-Chief Alex Shams and is an introduction to guest contributor Lila Yomtoob’s article. Lila Yomtoob is an Iranian-American filmmaker whose latest project is entitled America 1979. The film explores the experiences of an American family of Iranian heritage during the Iran Hostage Crisis, when a group of Iranian students took over the US Embassy in Tehran in response to the US Government’s decision to host Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the recently ousted US-backed dictator of Iran.

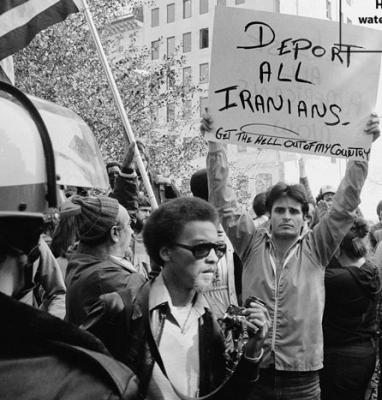

The film is one of the few explorations of Iranian-American experiences during the wave of anti-Iranian hysteria and violence that overtook the United States in the wake of the Hostage Crisis.

***

The Iran Hostage Crisis was a seminal event in the experiences of thousands of Iranian-Americans. Although many Iranians had settled in the United States in the decades prior to 1979, they had largely blended into the seemingly undifferentiated mass of olive-skinned immigrants who poured in following the repeal of the racialized immigration quotas in 1965.

The Hostage Crisis dramatically transformed how Americans understood Iranians as well as how Iranian-Americans viewed themselves. Once peculiarly exotic, Iranians suddenly emerged as the primary targets of a xenophobic American rage that led to a wave of hate crimes and widespread discrimination.

These experiences traumatized an entire generation of Iranian-Americans as well as the thousands of newly-arrived Iranian refugees pouring in to escape the revolutionary chaos of the homeland. This was a double shock for many Iranians; forced out of the only homes they had ever known in Iran, they suddenly found themselves afraid to go outside in what they had hoped would be a safe refuge. American support for the Shah had blown up in the US government’s face, but it was largely Iranians who ended up paying the price.

For those of us who did not experience the trauma of 1979 and the years that followed, our parents’ memories and stories have been largely inaccessible to us. The era’s legacy is primarily one of silence; Iranian-Americans have largely ignored their personal traumas and tried to move on with their lives, throwing themselves completely into the American dream and struggling to put the years of alienation behind them.

Others have kept silent for shame at the comparative comfort they experienced in America. While we were beaten up on the street, called “sand niggers” and “towel heads,” and denied jobs at every opportunity, our families in Iran faced the bombs and chemical weapons of a US-supported Iraqi invasion that ultimately stole nearly a million Iranian lives.

The film America 1979 is a crucial part of the Iranian-American community’s reckoning with its past, its present, and its future in this country. As a second generation rises in a historical moment with disturbing echoes of 1979 and its aftermath, Lila Yomtoob’s work offers us an opportunity to reflect on more than four decades of Iranian-American existence and to begin a conversation on the historical memory of a community living between Iran and America.

***

Even though I grew up eating khoresht, and hearing my parents speak Persian to each other (but not to me), and even though a grand Persian rug lined our living room, and foreign music blared from the tape player, I somehow didn’t know I was different from the other kids. I was born in Chicago and grew up in a multicultural neighborhood, with a Greek family across the street, an Irish Catholic family next door, and a Korean and a Filipino family down the block.

I was six years old when someone first called me Iranian, and it wasn’t a compliment. That is when I asked my mother: “What is Iranian? Am I Iranian?” This is when I learned the word Persian. “You are not Iranian, you are Persian,” she responded. My mother was a gentle woman, but at that moment she was mad at something bigger than I could understand. I was only six years old, but I understood that something was happening on television that made my parents frustrated. This is when I began to realize I was different in a bad way.

All along, my parents raised us to be as American as possible. They thought we would have an easier life without the foreign accent that might come from speaking a foreign language at home. They wanted me and my siblings to assimilate, and have the best life possible.

I slowly picked up on the details that made me different – my skin was a few shades darker than most. I had hair on my arms and other girls didn’t. The Hostage Crisis came and went, but the teasing continued, and even worsened as coverage of the Iran-Iraq War took the place of the Hostage Crisis in the media. In 4th grade, I shaved my arms with my dad’s beard trimmer, and when a friend noticed, I denied it.

In my teens and twenties, I actively denied that I was Iranian. In college, I thought about dropping my last name because I got so sick of people asking me that ubiquitous question, “Where are you from?” I would answer, “I’m from here.”

My parents’ choice to raise me as an American was a bold one that inadvertently backfired when combined with the racial hatred that sprung forth from the Hostage Crisis. I never quite fit in as an American, and I felt completely alienated from my Iranian-ness.

It was only when I started conceptualizing America 1979 that I began to proudly own my heritage and connect with the Iranian community. I have been writing this film on and off for years, and it has morphed many times. At first, the family was not Iranian, and the story was centered around a little girl who stole money from her brother for attention. Even though this was my own personal story, I made the family white American. I examined this choice for a long time and was surprised that I didn’t – that I couldn’t – make the experience actually reflect my own.

I decided to challenge myself and make the family Iranian. I placed my Iranian family during the Iran Hostage Crisis, because it affected me and my family dramatically, and I had something to say about it. And by giving them historical context, I could use every word, every plot and character choice, to humanize the family and steer away from stereotypes. Unlike media stereotypes, the parents are on equal footing with each other, and are loving and communicative. The kids are far from being the good children of immigrants.

It was also very important to me for American audiences to have an opportunity to hear the Persian language spoken in a gentle manner, one that did not include aggression or discussion of politics or religion. While none of this may sound unusual to an Iranian, it might be very unusual for an American whose only understanding of the Middle East is what they see on television.

I checked in with a few of my family members about my project to try to confirm that my early experience of the Hostage Crisis affected my identity. I asked my uncle, who is always cheerful and optimistic, what it was like for him when the Hostage Crisis hit. “It was soooooo baaaaaad.” He said it over and over again, and it took a while before he could say anything else. I had never bothered to ask my Uncle about this in the past, or any family member for that matter. When he reacted so strongly, I realized I hit a nerve and that I should make this film.

Another relative of mine said, “Why do you want to make a movie about that? No one cares about that.” He was very defensive. “Everyone was very nice to me and sympathetic. I had no problems.” I assumed that this was a sore subject for him, and I respected his boundaries.

I spoke to a few other older Iranian men who work in entertainment, and I got similar responses. It was very discouraging that I could hardly have a dialogue about the film. Then I spoke to an old classmate of mine who had studied extensively the effect of 9/11 on Muslim children living in America. She understood the worth of the film immediately.

I started talking to first generation Iranian Americans about it, and the stories came pouring out. Younger people had so much to say about the Hostage Crisis, about growing up “other,” whereas the older generation never had a chance to heal from the blatant racism the Hostage Crisis brought to their lives. I also spoke with minorities of other backgrounds, and they could relate to the film completely. White Americans were either fascinated or perplexed by the film, but could could only understand it from an outside perspective.

The process of writing the film was also a process of self-examination. I began to embrace my Iranian-ness. Besides my love of food, and my innate ability to curl my wrists when dancing to Persian music, I noticed my unique use of the English language, which I always attributed to being a creative person, is distinctly Iranian. My politeness, my sense of humor, my sensitivity to beauty, my care for others, and my hot temper – these traits are not just my personality, but they are part of my cultural upbringing that I now notice in other Iranians, and I love it. I get excited when I hear Persian, if I see a Persian name in the credits of a film, if there is an art exhibit to attend, or a new person to meet.

I am telling this story because many people don’t, and I am making America 1979 to give viewers a chance to come together and talk. When the film is finished I plan to screen it through schools and organizations, and get conversations going about the Iranian-American identity and the first generation experience.

My hope is that the film will open a door to a dialogue that will encourage closeness, healing and community. The desire to assimilate and achieve the American Dream has blocked the effect of the Hostage Crisis from our collective consciousness, even though it so so strongly shaped the Iranian American identity. And now, in the post-9/11 era, all Middle Eastern people are subject to the same, if not worse, racial profiling, against which we have to take a stand. I hope that by talking about these issues, and by owning this reality, we can move forward into the future with a more cohesive and proud voice that is free of the stigma of the past.

In order to move forward with the project, financial support is critical. We are nearly 40% funded and have until August 20th to raise a total of $21,500. We plan to shoot the film in September and have it finished and ready to share by mid-November. Please help us in this mission by going to www.igg.me/at/1979/.

America 1979 is made possible in part by a grant from the Brooklyn Arts Council, and is fiscally sponsored by Fractured Atlas. All donations are tax deductible.

6 comments