“Calligraffiti:1984-2013,” runs from September 5th to October 5th, 2013 at New York’s Leila Heller Gallery. As an updated version of the original show in 1984, the current exhibition features nearly fifty artists from the Middle East, North Africa, Europe, and North America. The article below also contains segments of an interview with French-Tunisian street artist eL Seed.

The interplay between word and image– of language and visual representation– has become complexly intertwined in the cultural productions of contemporary societies. The art gallery combines text and image; most installations are accompanied by a placard revealing information about the piece such as the name of the artist, the materials used, as well as the name of the work and when it was created. Here, the word becomes a conveyor of meaning, which elucidates the content of the visual material. The textual is treated just as an instrument in the service of the visual. However, in the cases of calligraphy and graffiti– two separate but undeniably related art forms– text itself is the object of beauty. The word merges with the image itself and the dichotomy between the two is nullified; no one can say when the letters end and the image begins, or vice versa.

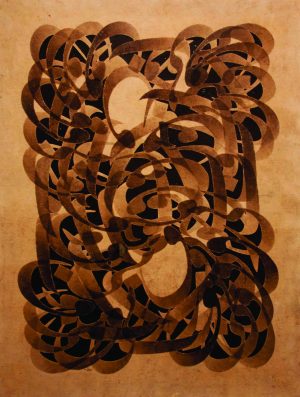

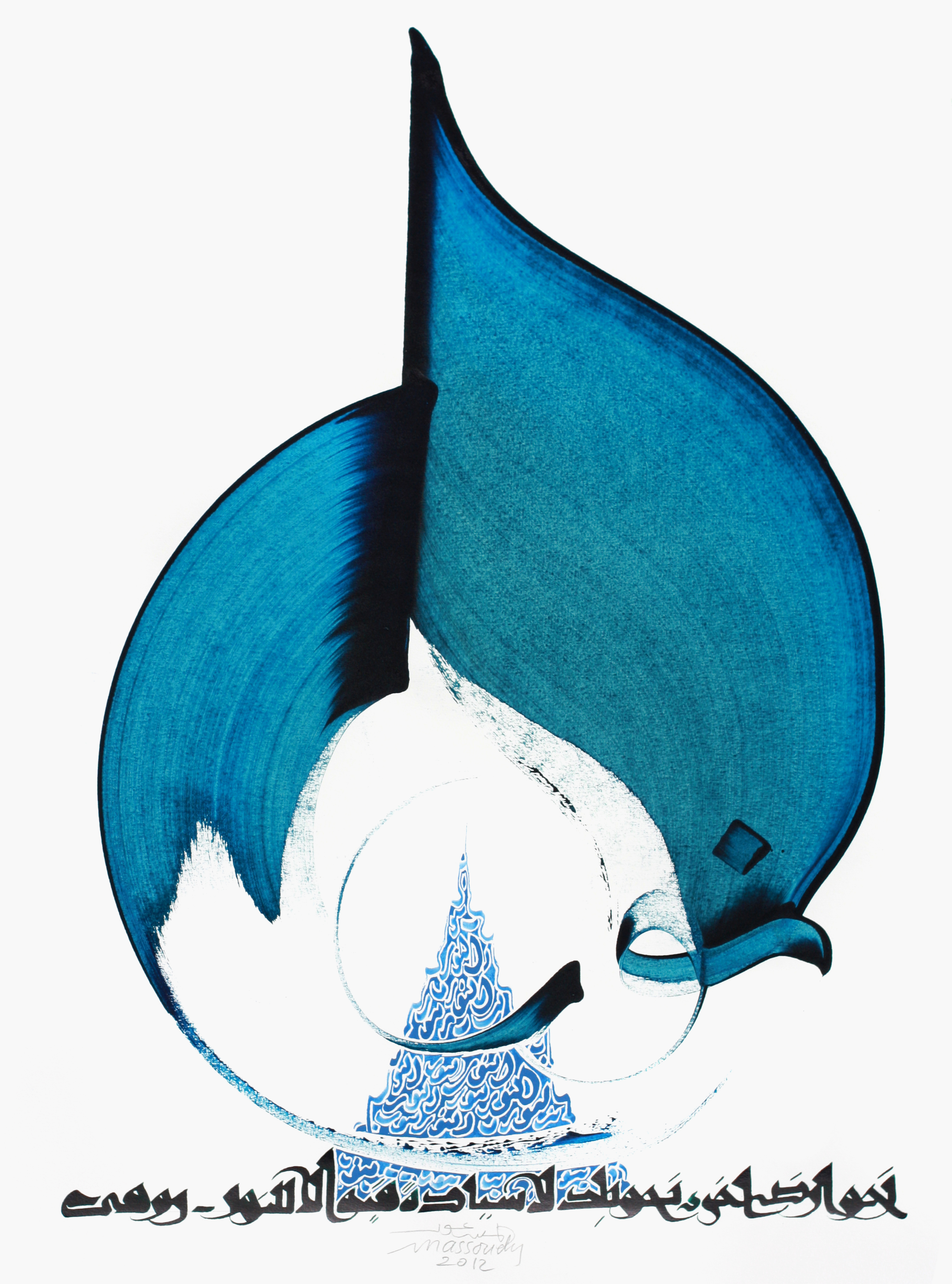

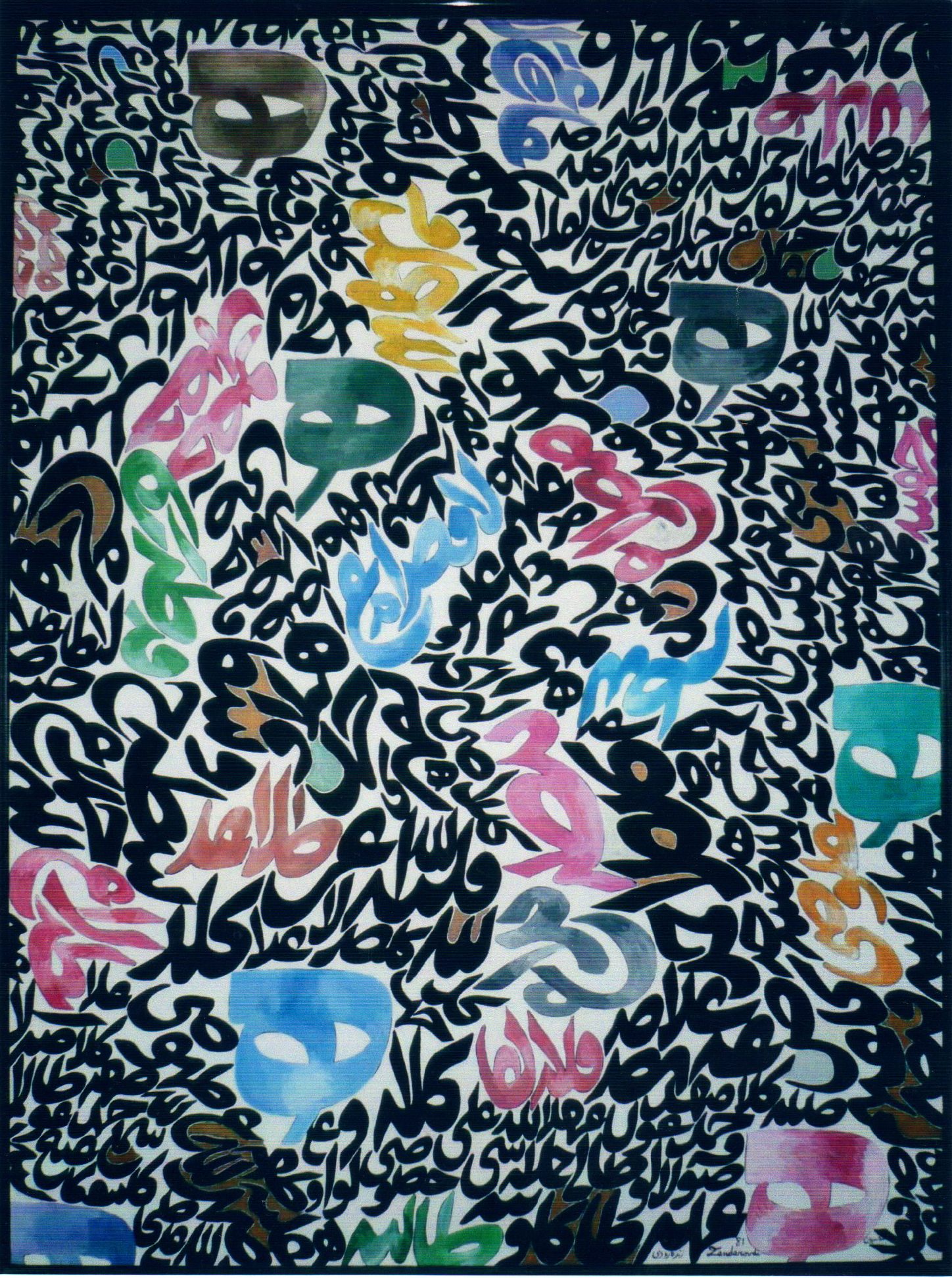

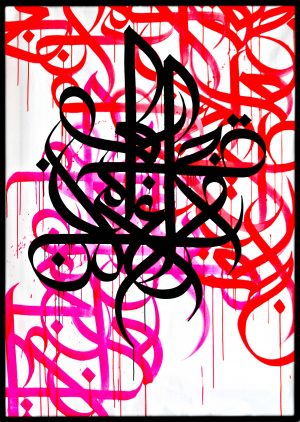

This synthesis of linguistic signs and visual representation is explored by New York’s Leila Heller Gallery in their new exhibition entitled “Calligraffitti: 1984-2013.” The show features a substantial collection of text-based visual art created by artists such as eL Seed, Parviz Tanavoli, Hassan Massoudy, Hossein Zenderoudi, Shirin Neshat, and many more. The show’s titular portmanteau points to another unification: that between graffiti and calligraphy. With the majority of the featured artists originating from the Arab world and Iran, the allusion to the regions’ traditional calligraphic practice is prominently displayed. The influence of early Islamicate styles such as floriated Kufic and Nasta’liq’s siah mashq are clearly visible in the innovative works.

For centuries, these calligraphic styles were utilized on a variety of media both within private and the public spheres. Arabic calligraphy was first used to transcribe the Qur’an, transforming the oral message of the faith into a holy textual source. As an object of patronage, calligraphy was most commonly associated with the arts of the book; highly ornate items were produced for the courts of various rulers to be housed in their personal libraries. Conversely, it was also used to decorate architectural structures that were accessible to the urban populace. Etched into stucco or painted onto tiles, the art form was exhibited particularly on religious buildings such as mosques and shrines. Such public inscriptions were also embedded with a political purpose: to display and legitimize the power of ruling dynastic elite and to emphasize their relationship to the divine. Thus, calligraphy functioned as a transmitter of messages as well as ornamentation in both open and closed spaces.

While traditional calligraphic practice is still alive and well today in the Middle East and North Africa, a trend towards abstraction came about in the 20th century as part of a wider movement that experimented with modernist form. This innovation in calligraphic design was introduced in 1960’s and 1970’s through new artistic movements such as the new “Hurufiyya” in the Arab world and the “Saqqakhaneh” group in Iran. Many of the pioneers of these new artistic movements such as Hossein Zenderoudi, Parviz Tanavoli, and Paris-based Iraqi artist Hassan Massoudy are featured in the exhibition.

.While this experimentation with the calligraphic tradition predominantly took place within the world of fine art, Arab and Persian graffiti artists were also reinvigorating text-based art in an urban setting. By the 1980s and 1990s, works created during the Palestinian Intifada and the Lebanese Civil War had attracted the attention of the media and academics, but had not yet been introduced to art galleries on a commercial scale. More recently, the cultural production of the Arab Spring has become widely acclaimed by many dealers and curators, creating a huge market for the work of street artists from the region.

One such artist who has recently risen to fame is eL Seed, who combines the artistic motifs of street art with Arabic script. While his work originated on the streets of Paris, his distinct style has been publicly showcased in metropolitan centers such as Montreal, Toronto, Doha, London, and Melbourne. Following the 2011 Tunisian Revolution, eL Seed has completed large projects in Tunisia such as a commemorative mural in Kairouan and the painted minaret of the Jara mosque in Gabes. Prominently featured in the exhibition of the Leila Heller Gallery, the French-Tunisian street artist agreed to discuss his work in relation to the exhibition.

As eL Seed explains, growing up in the diaspora was a primary motivation for amalgamating two distinct artistic traditions.

“I got into graffiti before writing and reading Arabic. I was born and raised in France, and I think the immigration policy toward immigrants is a failure. I don’t think that I, nor any one of my friends coming from North or West Africa felt French. When people tell you that you are not from here, you have the urge to ask yourself, “Where am I from?” So it came out of a quest of identity. In 2000, I felt the need to learn Arabic; I speak the Tunisian [dialect] but I did not know how to read or write classical Arabic. I took some classes and began to learn the language. It was many years later that I discovered calligraphy and I felt the the desire to incorporate it into my work… the combination of street art and calligraphy seemed natural since I see both elements as part of me.

At the beginning, I started to just write my name in Arabic script, but I wanted to get out of this particular paradigm of graffiti.. Instead, I decided I want to tell stories with my work; I got my inspiration from the Mu’allaqaat-i Saba’ — the seven hanging poems that used to be on the Ka’aba. In Pre-Islamic times, there used to be poetry competitions in Mecca, and the best poem would be embroidered onto black silk and hung on the Ka’aba. It was the face of the Arabic language. When people start learning Arabic, they are taught these seven poems because they contain all the roots of the Arabic language. In my mind, the message is more important than a name, so I erased my name and started to develop my own style.”

Like many contemporary artists utilizing text, eL Seed has not been classically trained in the art of calligraphy. Practitioners of traditional calligraphy developed their penmanship through the emulation of their masters. This chain of knowledge (or silsila) between masters and pupils emphasized formal configurations of a particular style such as Thuluth, Naskh or Nasta’liq. Additionally, the preparation of materials used for calligraphic designs were explicitly defined and often ritualized, becoming as significant to the painters as their finished work. eL Seed states that he has received criticism not only for departing from an established style, but by replacing the ink pen for the spray can, and paper for a wall or canvas. As he explains:

“I’m not a calligrapher, I don’t know any of the rules of traditional calligraphy; this is why I don’t call myself one. There are a lot of conservatives who believe that I am disrespecting a well-established tradition. But I wasn’t breaking any rules because I didn’t know the rules. You need to know the rules to break the rules.”

Similar to calligraphers, contemporary graffiti artists like eL Seed negotiate public and private worlds. Originally a movement defined by the urban setting, the artistic styles of graffiti that have decorated the street have been transplanted into the gallery space. While street art is still explicitly defined by its location in the cityscape, the last few decades have seen street artists bringing their work into galleries. eL Seed distinguishes his work depending on the locality.

“Private space is different than public space. Most of the pieces on the street are not commissioned. Anyone can come and add on or erase parts of it– actually, I had a similar discussion about this subject recently. I was doing a road trip across Tunisia and a journalist followed me the last day as I was painting two walls. They asked, “So what, you just paint a wall and that’s it? You don’t care what happens to it afterwards?” Of course I care about it, I hope that it can stay up as long as it can. I remember doing a piece one night and I came back the next day to take a picture of it, and someone had already come and scratched it out! When I’m painting it, yes it’s mine, but afterwards it doesn’t belong to any individual. You leave the piece to people, you don’t own it.

When art is made for a gallery or an exhibition, it is no longer “street” art. Instead, it’s art made by a street artist. When you put it on a canvas, it is not in the context of the urban space, it has no message. People usually won’t buy work done for a gallery because of the message, but for the beauty and aesthetics. Most of the time canvases are just an extension of what I do in the street… When you buy a piece, its yours forever, but on the street the piece doesn’t belong to you. However, participating in exhibitions is still important in order to live and to work as an artist; it’s an essential element. I can fund a one month project in Tunisia [through a gallery].”

The attention to Middle Eastern calligraphy in both the urban and the gallery space has had far reaching consequences for the perceptions of street art and the cross-pollination of international artistic motifs. The widely accepted view of art aficionados is that contemporary street art is predominantly a Western invention. eL Seed, however, challenges this narrative.

“A lot of the time people ascribe graffiti to North America or Europe. But you have examples of street art in Palestine in the 70’s, but people didn’t consider them artists when they were putting up their work. It’s a very hegemonic way of looking at art. They view Middle Eastern graffiti as a “version” of the real thing. People from Manhattan and Brooklyn were not the first people to paint on walls! You have people using spray paint on walls all over the world, so we need to educate people about that.”

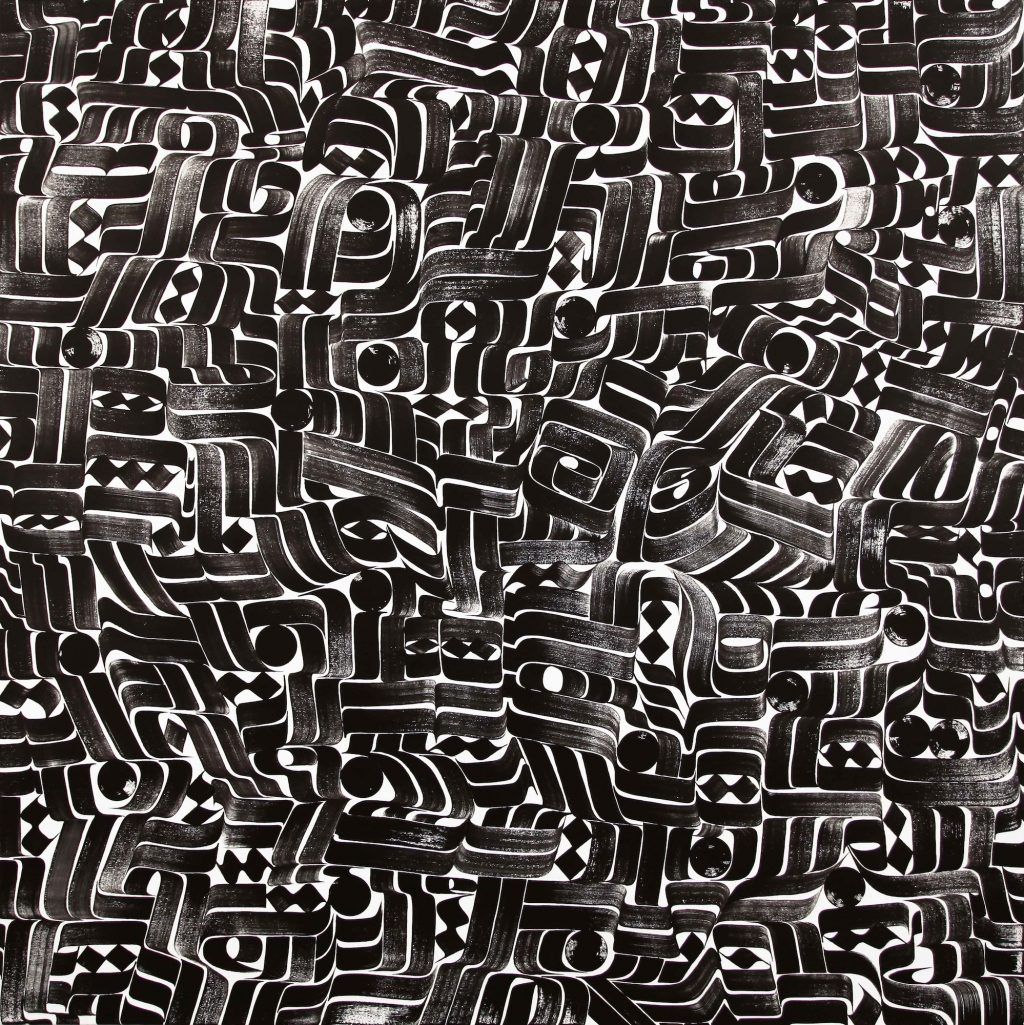

This exposure to Middle Eastern and North African art has even led to the adoption of particular styles by various people not from the region. For example, Rostarr— a Korean-American artist featured in the gallery has introduced the letter forms of Arabic script into his work. Using a paint brush and sumi ink (prominently featured in East Asian art), Rostarr amalgamates various materials and stylistic motifs to blur the lines between regional-centric classifications of visual art. Similarly, eL Seed speaks of L’Atlas, a French artist who has also been influenced by Islamic and Middle Eastern calligraphic traditions. As he explains,

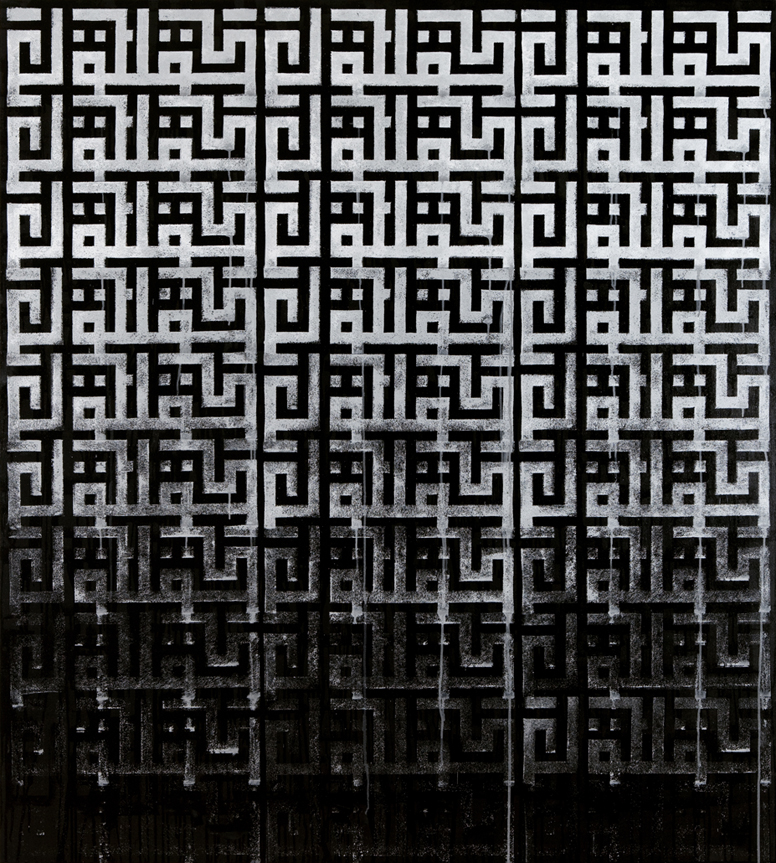

“L’Atlas, whose work is featured [in this exhibition], uses Arabic calligraphy that also appears to be written in French. If you look at his work here, you can see that L’Atlas has written his name throughout his work using Kufic script! It’s in Arabic but also simultaneously French and Latin. I respect this guy because he took Kufic to another level. Arabs didn’t do it with their own script– he had to learn and then was able to write in French with Arabic! That’s something I really enjoy– when you are able to understand an aspect of a culture and bring it into yours. Graffiti isn’t just taking from the West, it’s much more mutual.”

“Calligraffiti: 1984-2013” presents us with works that are pushing the boundaries of both word and image until they are unified. They demonstrate how the visual form of lettering carries both a signified meaning and an aesthetic quality. Additionally, these works show that calligraphy is not bound to its historically designated locus as a purely “Islamic” or “Middle Eastern” art, just as graffiti is not the sole domain of “Western” artists. Persian and Arabic scripts no longer belong to just Persian and Arab artists; calligraphy has been integral to a new aesthetic that influences artists from around the globe. By presenting artists like eL Seed who work between various social contexts like the open street and the gallery space, one can see how practitioners of both calligraphy and graffiti straddle the perceived public-private dichotomy. This flexibility and mobility allows “calligraffiti” to span stylistic, temporal, spatial, and regional limits to become a cosmopolitan art form.

5 comments

Great Post! One small correction: the top image can’t be from 1994. Pilaram died in 1982.

Thanks for pointing this out! The details of each work were provided by the gallery. here, the date listed is 1994. I wonder if the date refers to the acquisition of the work.