Kamyar Jarahzadeh recently spent two days with Ajam Band in London as they prepared for a concert. The following piece is based on his experiences speaking to the band and tagging along as they prepared for their performance.

“You know, I’m a transport planner, and in my field, they always talk about sustainable development,” said Amin Ajami, lead singer of Ajam Band. “And I want to see something similar for Iran; I want to aim for sustainable cultural development … Our culture has to be something that has roots in the world of those people, yet still flexible enough to grow and create a place for the people themselves to connect to it and create a connection with it. There always has to be a clear future for the culture.”

In a sense, London-based Ajam Band is the musical form of this dream. Since 2010, Ajam Band has been creating a unique and distinctly Iranian sound. They have five formal members but also maintain a rotating cast of Iranian musicians who perform on recordings and tours. None of the members are full-time musicians, and they balance their various day jobs with performing and going on tours.

In Ajam’s music, tars, tanbours, kamanches, and other traditional Iranian instruments are brought together over deep basslines, subwoofer-shaking 808 drums, and the kind of production values that sound more like hip-hop than the standard low-budget aesthetic of most Iranian pop songs.

The music is not simply Persian, but instead distinctly Iranian, drawing on the many musical traditions within Iran including those of Kurdish, Azeri, Baluchi, Turkmen and Arab Iranians. The band’s groundbreaking approach to Iranian music has garnered their videos and songs thousands of hits online, and they are even a presence on Iranian satellite television.

In some sense, Ajam is what many Western music critics would call a “World Fusion” band, mixing Iranian and various modern non-Iranian musical styles to create their signature sound. This framing, however, is problematic in many ways. The very term “fusion” itself implies a hybridity between two separate and totally distinct styles of music. In reality, Iranian musical traditions are highly diverse between languages and even across regions, with different musical approaches, forms, and instruments in use in different traditions.

Yet by considering Ajam Band a “World Fusion” act in the traditional sense, we are collapsing all diverse traditions that make up Iranian music into one artificial category, and relegating any musical form deemed non-Iranian to another category. This implies that Ajam is simply taking an Iranian cultural music tradition and fusing it with something new to create a more “modern” musical form.

The fusion in question is much more nuanced. For Ajam Band, the fusion begins by combining various musical traditions within Iran, and then selecting certain elements of non-Iranian music to also complement this mix.

Lead singer Amin Ajami rejects any attempt to call their music simply as an attempt to update or modernize Iranian music. Instead, he refers to their music as an Iranian postmodernity that is being shaped not for the sake of some abstract idea of modernity that demands a curtailing of all that is non-Western, but instead to recontextualize Iranian traditions in today’s milieu (musical and otherwise).

Ajam’s song Beshkan features instrumentation and singing in Persian, Kurdish, Azeri, and Arabic.

As an example of this recontextualization, Amin explains the presence of deep sub-bass in Ajam Band’s songs, a feature that does not exist in classic Iranian musical forms. Just as hip-hop and dance music has been known for the presence of speaker-rattling bass, Ajam’s inclusion of this musical element allows the music to be played against today’s songs to the same, booming effect. “[Our use of] bass, for example, is something necessary,” Amin says. “In our music today, if there’s no bass, we think it’s something just for certain situations. It’s not music for your daily life anymore that you can just put on anywhere. You have to be able to feel the music.”

Even in their more intimate live performances, Ajam Band’s producer and percussionist Nari-Man adds a deep bass texture to the music with the help of a sampler or a drum kit.

“And really, you can’t just reject today’s taste in music. You’re lying to yourself if you say I’m just making Iranian music, because I am only Iranian myself. The mix between your culture and today’s culture has embedded itself in you…and your whole life.” Whereas past cultural and musical movements in Iran have tended to emphasize one ethnicity or vision of Iran over others, Ajam’s music seeks to embrace these paradoxes.

As Amin himself says, the strict dichotomies people often try to suggest create being Iranian and Western, modern and religious, cosmopolitan and nationalist are not realities that exist or can be made to exist in life.

“They look at me, and I wear a tasbih and a Farvahar [at the same time],” Amin says. “They say you can’t do that…But show me a culture that doesn’t have paradoxes. I think the things we assume are paradoxes are where the culture’s real beauty lies, because it shows that culture comes from a collective’s consciousness.”

Again, this is why a Western conception of Ajam Band as a simple “World Fusion” band does not adequately capture the scope of the cultural vision Ajam is offering.

At the heart of Ajam is an understanding of Iran that is inclusive of all the cultures, religions, and ethnic groups that comprise it, and chooses to casts off cultural divisions for the sake of highlighting the beauty in similarities and differences between different groups in Iran.

Indeed, Ajam has faced serious criticism from those who seek to enforce these cultural boundaries. Amin often referenced the various messages and Youtube comments he sees with people attacking the name “Ajam” itself. Historically, the term has been a term used to refer to non-Arab groups in West Asia during and after the Arab conquests of the region. The word can also be derogatory in effect, as it suggests someone who is illiterate or mute (i.e. someone that does not comprehend Arabic).

Similar to us here at Ajam Media Collective, the band has explained in many interviews that they took on the name as a way to reclaim this historically derogatory name for Iranian people as an inclusive identity for all Iranians. Therefore, not only is the band’s fusion of electronic and “modern” sounds unique, but their music draws extensively on fusion between musical traditions from different groups within Iran itself, with languages like Arabic, Persian, and Kurdish coexisting in the same song, and alongside dialects and phrasings from the people of the Alborz Mountains and Caspian Rim, the foothills of the Zagros Mountain ranges, and the Iranian Plateau. Yet while critics may be politically uneasy with this fusion, Ajam’s music represents a complex hybrid reality more than something radically different.

In my two days with Ajam in London watching the band practice, relax, and prepare for a performance at Toronto’s Tirgan Festival, the falsehood of these supposed dichotomies that purport to define Iranian identity was often made apparent. This was true not only in light of the everyday multiculturalism and cosmopolitanism that Ajam creates in its music, but as the individual band members live in their everyday lives. The lines between British and Iranian, and even between the different ethnic identities that make up Iran and its neighbors were a point of celebration instead of conflict.

Just as in their music, the individual members of Ajam cross borders in their everyday life. During breaks from practice, the band took turns playing classic Arabic and Arab-Iranian style songs, only to later have dinner at a local Turkish restaurant while trying their best to speak with the waiters using the known shared words between Persian and Turkish. To top it all off, the members of the band recreated one of their professed hobbies; practicing the uniquely syncopated Gulf-style to clapping to various Gulf pop hits they played at full volume while driving through London.

“The idea for the video actually came from us doing this regularly,” Parham explained.

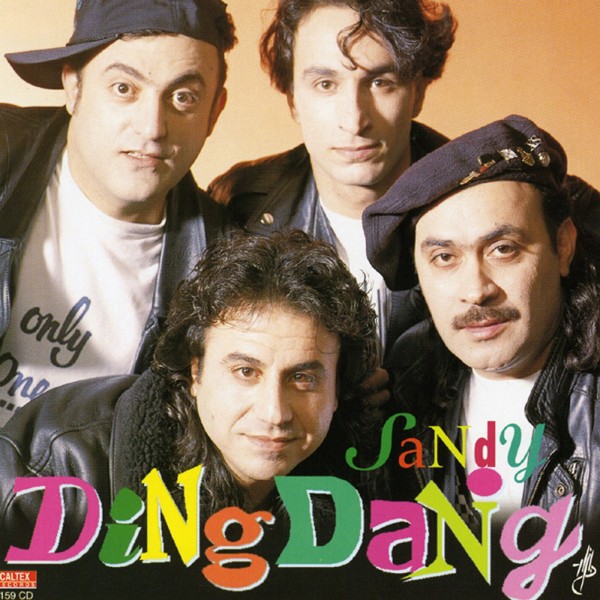

How does the band see itself? Put it his way: as we sat around having tea after an all-day practice session, Parham went over to the stereo system and put on Sandy, an obscure 1990s-era Iranian pop singer.

To most Iranians, Sandy is known for his energetic and now dated takes on Southern Iranian music and its “Bandari” style, featuring all the drum machine and synthesizer sounds that instantly trigger nostalgia for the 80s and early 90s. A native of southwestern Iran’s Khuzestan province, Sandy’s music has become a canonical example of pop in the Southern Iranian style.

Sandy was a prominent Iranian music star, but when most Iranians think of him and his trademark Nike outfits, they think more of a pop novelty of a bygone era rather than a timeless virtuoso.

Despite this, Parham was singing along and moving to the music as he explained the subtleties of the distinctly 1980s-style bass lines, composition, and samples that comprise Sandy’s comically dated production values. In the midst of all this, I found myself laughing at Parham and insisting that there was no way a musician of his caliber could actually be appreciating what is considered some of the most clichéd Iranian music. Ajam comes off as the sophisticated incarnation of Iranian popular music that is supposedly the antithesis of typical Western-imitating Iranian pop. How could one of its members claim to be a fan of its own apparent musical foil?

But Parham insisted that his appreciation for Sandy was not in jest. “We grew up with this music,” he said. “At the time, it was like nothing we ever heard before. And if you think it about, he did the same thing that we are doing with our music; he took the music of his culture and mixed it with the sounds of that time to keep it alive.”

Parham lived through decades of the evolution of Iranian music, and he has now come to partake in that change. He seems to suggest a more honest way to view the history of Iranian music and its future without viewing music solely as a battleground for cultural conflicts or dichotomies. Instead, music is a sphere where reality and the fantasies imbued in it can simply manifest free from ideological boundaries that people tend to impose.

In a world where politicians like to create and emphasize differences between the so-called “West” and Iran, and even regional differences in the country itself, Ajam Band and its musical forefathers allow us musical glimpses of Iran that embrace paradox and encourage Iranians and non-Iranians alike to turn to their identities, as mixed and incoherent as they may be, as a source of pride.

As they sing in their song, Raghse Mardooneh, “Be har chi keh hasti eftekhar kon, baa har chi keh dari ebtekar kon.” “Whatever you are, be proud of it. And with whatever you have, innovate.”

2 comments