We all know that poetry precedes written language. The songs, hopes, and dreams of people did not wait millennia to get recorded, and we should be glad, because we still remember Odysseus, Gilgamesh and Manas. And even in the 21st century you will hear the occasional curmudgeon saying that kids nowadays should learn poetry by memorization, not by reading. That sounds silly until you come across the kind of uncle who can recite passages from the Shahnameh from heart thanks to his Alborz education.

Decoupling story from text sounds a bit absurd now, but only a century ago it was a way of life. A storyteller does not just choose his story, but chooses how it will be disseminated. The text chosen – or no text at all! – is just as political a choice as subject matter, and governments would crack down hard on people who chose wrong. Imperial Russia, the ruler of five scripts, were especially severe about this, and Samizdat did not enter the historical record with the Soviets. So how does a culture keep its identity and its sustenance when cut off from their historical handwriting? They rely on a man like Abdullah Tuqay.

Abdullah (or Ğabdullah, Габдулла, or عبدالل for reasons that we will soon discuss) was born to a Tatar mullah in 1886. Now, the beauty of the Ajam platform is that there is an audience that refuses to be turned off at the sight of a yumuşak g, let alone all the madness that follows it. The always-fantastic Jake Turk has a great background reader on Tatarstan, the home of Tuqay and known if at all to Europeans as the place where Ivan the Terrible first earned his reputation. But Tatar life did not end with Russian suzerainty, and the centuries of Russian rule over Tatarstan include a complex negotiation of power.

Abdullah was born into this at the end of the nineteenth century into a bureaucratic household at the breadbasket of the Russian Empire. Abdullah Tuqay’s early life is a bit Dickensian. He passed from a dead mother to a grandfather in penury to a Kazani coachdriver, who later brought him to a bazaar where a leather tanner took a liking to the young boy. The tanner and his wife became sick, however, and he was sent back to his grandfather and then to a farmer, who put the boy up in a madrassa. By this time, a wealthy family member in Uralsk (a town in now-Kazakhstan 500 kilometers north of the Caspian shore) took him in and brought him to Russian school. Abdullah Tuqay was ten years old.

It is a sad beginning, no doubt, but Abdullah wrote with such brightness and enthusiasm that one wonders where it could come from. It would be nice to say that it came from Tuqay’s Jadidi teachers, who imbued in the youth a sense of pride and connection to his community. For this was the spirit of the Jadid movement explained so well by Adeeb Khalid and embraced so theatrically by Molla Nasreddin. The movement was an anti-imperialist and anti-clerical mission to imbue pride in the locality and the community in Central Asia. They promoted religious and political reform based on tenets of equality and modernism, not much different than the Protestants of old or their Constitutional Revolutionary contemporaries in Iran.

The truth is probably that the young Tuqay was quite a bit sharper and more perseverant than most of his classmates, and that he benefited more than most by visits by traveling Turkic master poets (these writers with their anti-authoritarian streaks did better relying on ta’arof than on patronage) and a teacher enthused about creating a new language for his students.

It is now in our story when Tuqay gets to pity the Americans. His contemporary, T.S. Eliot, was constrained by his language. Tuqay was integral – at the age of twenty – in creating a new one, bringing Tatarça into the Cyrillic alphabet. By this time, Tuqay moved to the Volga Tatar capital of Kazan. Kazan was and still is very much a cultural capital. Much like Tabriz, Kazan straddles a river and acts as a border entrepot. Intellectual (or literal) refugees from Moscow, Tblisi, Crimea, or Bukhara brought their ideas and their books. The Tatars themselves were of course their intellectual and creative equals. Tuqay stayed in a hotel full of young and brash youth from throughout the region, and spent days hunched over the press and nights shouting over a table. The magazines, feuilletons, broadsheets, chapbooks, and anything else that Tuqay’s crew could put in an iron press and later bound were full of religious or secular, pro-Empire or pro-Caliphate or pro-Republic, essays or diatribes or dialectics. The only rules seemed to be that it had to be written in “Tatarça” however defined and that it had to be written well.In such a multiconfessional, multiethnic, and multifarious city, Tuqay aimed mainly to have the cream of the literary class rise to the top.

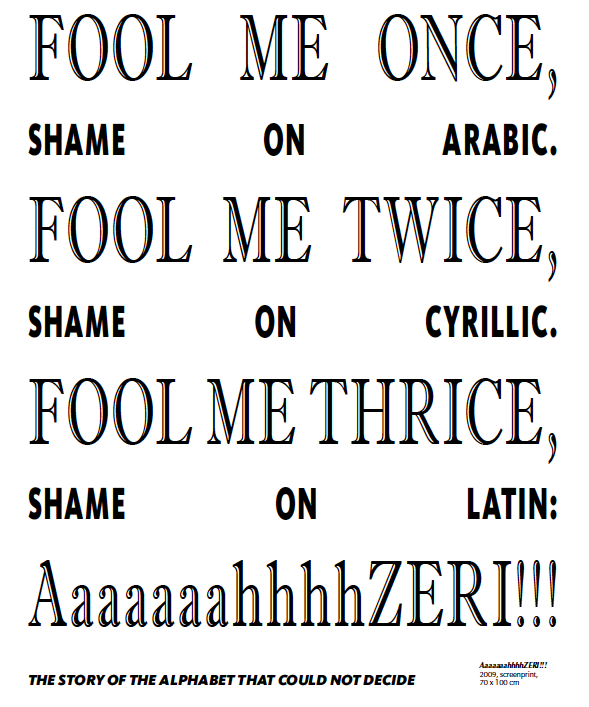

So what is this Tatar language? This Tatarça of what we speak? It has its origins in the Kypchak Turkic language spoken today predominantly in Kazakhstan and historically also by the Mamluk rulers of Egypt. Tuqay and his cohort added in some Russian vocabulary, but it was formed as much as through the ingenuity of Jadids and Tuqay’s hotel full of excitable young men as it does necessity. In 1906, police seized his Iske Imla (essentially, Arabic) typefaces. Things would be written in Cyrillic from hereon out, or not be written at all.

This was not the Russian Empire being capricious and cruel, nor was it about westernization and modernization. It was about power. Michael Hancock-Parmer discusses the political uses of Arabic, Cyrillic, and Latin scripts in a 21st-century context, but the lesson holds true:

In essence, “Arabic-script Kazakh” is nearly a contradiction in terms. When written in Arabic script, Kazakh, Tatar, Bashkir, and Karakalpak appear much more identical then then do in the current Cyrillic alphabets. Moreover, their close relationship with Uzbek, Uyghur, Kyrgyz, Turkmen, and Ottoman-Turkish was far more apparent. Though much ink has been spilled attacking the awkwardness of Arabic at correctly carrying Turkic language, the longevity of the alphabet must be re-considered rather than seen as a sign of backwardness or Oriental decadence. Rather, the very limitations of the Arabic script (i.e. writing of the various Turkic vowels) might be considered as its strength. In essence, while the Arabic script was able to add letters to represent vowels (modern Uyghur in China is an excellent example), the obscuring of the same vowels allowed for easier comprehension between speakers with different pronunciations. One can see a rough analog with the ratio of English written vowels to pronounced vowels; many differences in pronunciation are obscured, allowing much easier communication (in writing) between speakers in northern and southern portions of the United States, to say nothing of between Australia, India, England, the US, etc.

Cyrillification emphasizes difference where there previously was little to be found. Dialect went from being the sort of thing joked about to a matter of otherization. And this was not due to the unruly Turks (ethnic group not the empire) or due to the dastardly Russians (empire not ethnic group) but due to an eagerness for power and suzerainty. A new script cuts a society off from their history – literally rendering it illegible – and forces the way of the empire as the only way of societal advancement.

Abdullah Tuqay fought against this. His “New Tatar” was stripped of Arabic and Persian loan words beloved by the ulema but incomprehensible to the vast majority of Tatars., but the press’ ability to disperse not religious or educational tracts but fun and thoughtful poetry made Tatarça a force for inclusiveness. Handcuffed by imperial power, Tuqay and his cronies did their best to preach inclusiveness and fraternity, writing:

Banish enmity, its time has passed.

Friends – separated bodies,

But in our hearts, forgetting evil,

United forever.

A member of the 27 Club (done in young by consumptive pneumonia), he has taken on a bit of cult-hero status as well, with statues in Moscow and Kazan. It doesn’t hurt that he was a bit of a hunk.

Slavs + Tatars poke fun at the confusing history of Azeri (on page 46) but the trans-Caspian Turks are hardly alone. They are well-footnoted and brothers in anti-modernisme, but they and we both know that you can’t live in the past. Abdullah Tuqay knew it too. Fierce polyglots in a monoglomaniac world, we are forced instead to link to a short list of Tuqay’s poems translated into English and use metaphor to explain our changes in mood and tongue:

As any guest to a Russian apartment will know, changing into slippers upon entering is a given. Russian in public, Tatar at home. The threshold between languages was seen this way, with speaking Tatar in public would be as though one wore one’s slippers on the street and to work. Cosy they may be, but not “prilichno.” Just not done.

So incredibly lost to the Anglophone world, Tuqay lives on in spirit. And to let you in on what has always been a poorly-kept secret, I created The Tuqay just to embrace this coziness. It was created to be loud and argumentative, to tell great stories and give gripping lectures. It was created to have fun. Language is supposed to be sung, not pointed at (though if you must, at least be beautiful with it). Start from the left, start from the right, it does not matter; share the stories and the land will follow. Tuqay would be happy to bring storytellers like the Kyrgyz Manaschiler and the Azeri Mugham ifaçıları together on one press, if he could afford the paper costs.

The Tuqay doesn’t have to worry about such silly things in the 21st century (though there are .pdfs!) so instead it proudly works in his image. The eastern (but not easternmost!) brother of Mashallah and Ajam MC is a newborn, proud and happy, and would like nothing more than for you to join it in these emotions.