This essay is the first of a three-part series on Pakistan’s contemporary rap movement. The findings of these essays are based on conversations with twenty-three Pakistan based rappers.

Rap’s transition from the poetry of marginalized African American communities to the mega-hits circulating in mainstream America today draws fierce debate. Consumerism and commodification are frequently found guilty of eviscerating a once-radical movement with the market’s golden handcuffs, swapping its class politics for “mere spectacle.”

In contrast, Western popular and academic assessments of rap’s journey beyond American borders, particularly in the “Muslim world,” are markedly inattentive to this commercialism. Instead, this rap evokes a virtually unanimous nostalgia. There, 1986 Los Angeles is found alive in 2013 Lebanon, and New York’s Public Enemy and L.A.’s N.W.A are discovered rhyming through Beirut’s Rayess Bek and Tehran’s Yas. So prevalent is this penchant for locating the dissent lost in American rap in “over there” rap that the Washington D.C.-based think-tank, Middle East Institute, finds Iran’s Ayatollahs battling a reanimated Tupac, and Wall Street Journal has rappers soundtracking revolt from Egypt to Iran.

The anachronism of finding 1980’s Ice Cube in contemporary Islamabad can be plausible only if one abundantly ignores the realities of contemporary rap. In a landscape where middle class white purchasers have dictated the contours of the genre’s production since at least 1992, it is particularly absurd to impose upon non-American “Muslim” rappers the romantic notion that their rap is protest.

Imagining a resurrection of resistance in “over there” rap shortchanges the breadth of the non-American musical movements. Instead, they are much more productively seen as artists in the peripheral markets of globalized rap. Such a lens appropriately situates the rappers, and accords their work the creativity and artistry it deserves.

photo credit: Rap Engineers

Far from culturally-appropriate replicas of bygone American rappers, Middle East and South Asia rappers are creators of an entirely new art, vastly expanding the frontiers of the genre. “It may not have started in our communities, but just like cricket”, says Islamabadi rapper Xpolymer Dar (Muhammad Dar), “we have made rap our own.”

Indeed, in Dar’s country of Pakistan, where rap is a growing underground music genre, the ‘80s American rhymes for race and class justice are judged to have little resonance with Pakistani realities. Instead, it is the stylings of hyper-commercialized contemporary artists such as Eminem and 50 Cent that find ears, and have provided the launching pad for contemporary Pakistani rappers.

Eminem, 50 Cent and Bohemia: Language, Vernacular and Rap

Prior to this most recent spike in the popularity of rap among Pakistani musicians, the genre’s heyday would likely be located in the early 1990s, when acts such as Fakhar-e-Alam enjoyed a broad audience. Alam’s hit track Bhangra Pao held the number-one spot for 28 straight weeks in local charts and was among the first Pakistani songs to be featured on MTV Asia. Indian and South Asian diasporic rappers such as Apache Indian and Baba Sehgal too found their tracks bumping across Pakistan in the 1990s.

Pakistan’s contemporary rappers, however, rarely trace their roots to that rap tradition. In fact, many take reminding to even recall the productions of the 90’s decade. Today’s movement, instead, is overwhelmingly a product of the globalization of commodified American rap. And if there is one American artist around whose productions penetrated Pakistani music stores, and whose face came to represent rap in Pakistan, it is Eminem.

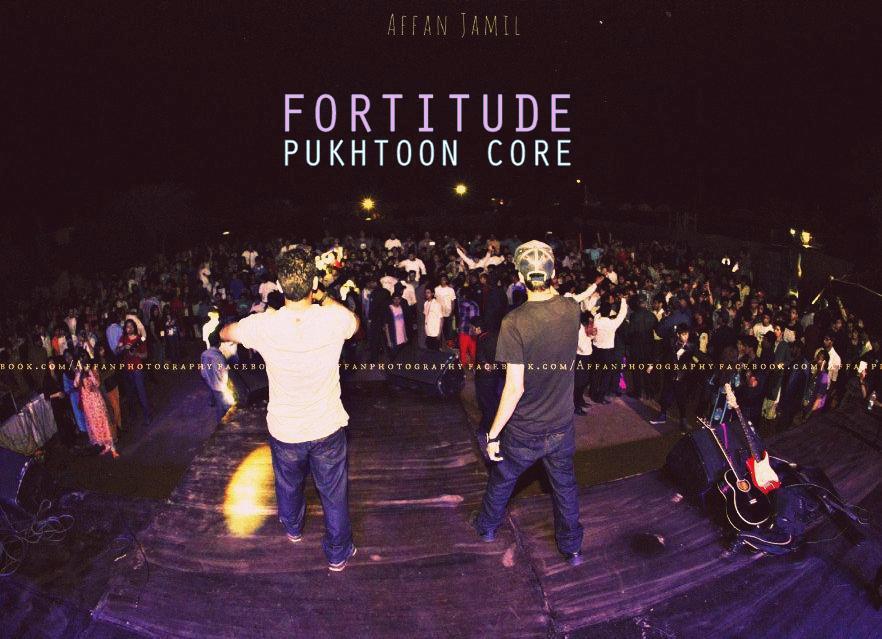

photo credit: Affan Jamil

From Peshawar, near the Pakistan-Afghanistan border, Party Wrecker (Mustafa Khan) of the Pukhtoon rap group, Fortitude, describes its introduction to rap, “I used to go to Shumail and Shahkar’s house and we used to sit and listen to Eminem.” From distant Karachi, Qzer (Qasim Naqvi) similarly describes, “I was eleven years old when I listened to Lose Yourself by Eminem, and realized the connection between my poetry and rap.”

Ali from the Lahore-based crew DirtJaw offers perhaps the most vivid example. A poet for some years, Ali was introduced to rap through the movie 8 Mile, featuring Eminem, and loosely based on the artist’s life. Having no idea who Eminem was, Ali nevertheless discovered the strength of poetry over beats, and began to transform his verses into rhymes.

During this time, a period beginning shortly after Eminem’s release of the Marshall Mathers LP in mid-2000 to 2005, rap remained a marginal artistic force in Pakistan. Rappers were dismissed as Eminem ki aolad (Eminem’s children), and yo-bache (yo-kids), the latter a construction on a caricature of American slang that accused Pakistani rappers of aping Western culture.

This all changed in February 2006, when goliath label Universal Music dropped the first commercially backed album of the Bay Area rapper, Bohemia.

A Punjabi Christian, born in Karachi, schooled in Peshawar, and raised in working class minority communities of the San Francisco suburbs, Bohemia’s raps emerged from experiences such as seeing one best friend murdered and several others sent to jail. Pesa Nasha Pyar (Money Drugs Love) was Bohemia’s second album and, like many his peers endeavoring to rap their way out of the ghetto, its content offered little departure from the glorification of violence, hypercapitalism, and drug abuse that are the hallmark of commercial rap production. For example, Kali Denali, among the album’s most popular tracks, features cocaine and marijuana abuse, and hostility towards the police.

Bohemia, however, was lyrically groundbreaking. His rhymes and a vast majority of his hooks (choruses) were in Punjabi.

With Universal’s distribution network, Bohemia found a ready market among Pakistanis, both in the diaspora and in Pakistan. In Pakistan, where just under half of the country speaks Punjabi as its first language, the introduction of a rapper rhyming in Punjabi dramatically expanded not just the linguistic frontiers, but also the cultural and socio-economic scope of the movement.

Class and linguistic politics in Pakistan dictated the contours of Bohemia’s uptake in Pakistan. Policies as diverse as the British Raj’s mid 19th century replacement of Persian with Urdu as the official language across the northwest of its colony, and the Pakistani’s state own tendency towards a linguistic centralization that privileges Urdu over indigenous languages, have created a politics of dominance that has marked Urdu with urbanity and associated Punjabi and other Pakistani regional languages with crass vernacularism. Although less than ten percent of Pakistan’s mother tongue, Urdu has been established by the state as a marker of national belonging. It remains the medium of national state broadcast, the official language of the country (alongside English), and the language with which high literature and culture is most commonly associated.

But if Urdu is the refined language of power and privilege, Punjabi is the powerful words of the streets. And the streets are where lyrics overwhelmingly situate rap.

For many middle income youth, for whom the elitism associated with Urdu is not resonant, Punjabi is not only the language spoken at home, but also that of the slang among friends, and of the banter with the fruit-seller and the bus driver. It is with this segment that Bohemia’s Punjabi most resonated, his lyrics lending themselves easily to the growing Punjabiyat (Punjabi-ness) movement in Pakistan, particularly its hypermasculine narratives. If Eminem was accessible to those Pakistanis who could imagine themselves fashioned in his image, Bohemia was for those rising rappers to whom Eminem had never seemed imitable.

Jhelum-based Kasim Raja, whose Punjabi raps arise from a deeply personal desire to reinvigorate Punjabi identity, provides insight. “I used visit my cousins in Lahore. In class 8, my cousin introduced me to 50 Cent… but it was after I heard Bohemia that I started to think that actually rap is a reflection of what is really true.” Billy X’s case similarly highlights the linguistic import of Punjabi in rap. An ethnic Pukhtoon who speaks Pashto at home and used to write his early raps in English, Billy now raps in exceptionally colloquial Punjabi, “because that’s how people speak on the street.”

The battlerap culture that was employed to inscribe hierarchies of lyrical deftness had until then been tilted in favor of those with a good grasp of English, that is, the socioeconomically privileged. With Bohemia’s introduction of Punjabi, the old battle scene was no longer the only game in town. Rappers who had hitherto written in English with limited success – a vast majority of those who constitute the contemporary rap scene – now found themselves rhyming in vernacular, drawing upon Punjabi street slang to diss with an indigenous punch. The yo-bache derision was yesterday’s news.

Not only did Bohemia’s appearance linguistically expand the Pakistani rap movement, it also sparked a change in the movement’s content and style.

The new rappers owned their product. Their rhymes, rapped in street vernacular, had now found a vocabulary familiar with representing their own experience. Jawad from DirtJaw highlights the new cultural space in rap lyrics that Bohemia’s music introduced. “I heard Bohemia and realized that rap is not just about bad words for girls and showing off – it is an art form.”

Kasim Raja’s track Black Hoods Black Sheeshay illustrates this indigenization of creative trajectory. While the track shares a celebration of braggadocio and automotive culture with commercial American rap, its engagement with alcohol is a radical departure from the substance abuse celebrated by Eminem and Bohemia, “Not into drugs / we’re into cars… Poppin bottles but only sodas / livin far from drugs, we’re against drugs / we’re against drugs…”

Just as Eminem and 50 had furnished not just a language but also a particular cultural fabric from which to fashion lyrics, the addition of Punjabi added both language and content to Pakistani rap. Themes of prominence in the Pakistani experience and their vocabularies of expression were soon reflected in rhymes. Take for example, Fortitude’s hit track, Pukhtoon Core that describes the fate destined for exploitative Pakistani elite in clear terms, “And these people will be rooted to the ground / Their lives are those of kafirs (unbelievers) and munafiqs (hypocrites).”

Far from a marginal phenomenon, entire discographies are now rooted in, and can be made sense of only through the Pakistani cultural conversation. Karachi rappers Ali Gul Pir and the Young Stunners crew provide two examples of this. Pir’s hits caricaturize such immediately Pakistani characters as an inappropriate rickshaw driver, a corrupt Pakistani politician, and the son of a Sindhi feudal lord. So popular was the last track that Pir was soon rapping on commercials for Pakistani cellular service giant, UFone. Young Stunners’ raps are equally embedded in locality. Twin tracks, both immensely popular, diss Karachi’s elite and the city’s middle income youth in slang barely comprehensible to the non-Karachite.

Vernacular raps added another new dimension to Pakistani rhyming. Rappers were no longer just rapping; they were rapping in their language, itself a socio-political statement. “Why should I rap in someone else’s tongue?”, says Jawad from DirtJaw, “I love Punjabi very much.” This sentiment was quick to catch on among non-Punjabis as well. Fortitude’s Party Wrecker describes his use of Pashto: “Rap is an avant-garde form of music in Pakistan right now, and I want to show that Pukhtoons are as progressive as other Pakistanis are.”

These vernacular raps also resonated deeply with fans. Xpolymer Dar from Rap Engineers, attributes the success of their hit, Conflict Management, a reflection on negotiating Pakistani socio-economic tensions inspired by the kalaam – the words and works – of Sufi poet Bulleh Shah, to the track’s rootedness in Pakistani culture. “When you don’t copy the U.S., and give your culture’s feel to your rap, that’s when people start to like you,” Dar reflects. Fortitude’s Party Wrecker echoes this assessment in his description of the instant success of their first Pashto release, Pukhtoon Core. “Pukhtoon people immediately liked it because it was their language, their culture.”

Can’t Stop, Won’t Stop

From Eminem’s introduction to Bohemia’s expansion, Pakistani rap continues to evolve both in conversation with and independently of global influences. Sub-movements run the gamut from following global rap trajectories, to looking inward into Pakistan for its development.

Satirists such as Ali Gul Pir and Faris Shafi, who rap deeply political rhymes, delivering their dissent through a comedic idiom, reveal a strength of politically engaged jokerap that is unparalleled in the American rap landscape. Similarly, the deep engagement of other, less comedic, Pakistani rap with the country’s socio-political narratives highlights the particularity of the music’s content to the country’s society.

The denigration of aping Western rap content also underscores the attenuation of Pakistani rap to the country’s cultural narratives. Criticizing Pakistani rappers who emulate Western content, Jawad from DirtJaw stresses the need for realness and authenticity. “Talking about drinking and doing drugs when you don’t is as fake as talking about carrying guns and killing people when you don’t do that.” Stressing the irrelevence of the hyper-violent rhymes of American gangsta rap to middle-income Pakistani lives, Kasim Raja is even less generous. He emphasizes his refusal to collaborate with artists whose lyrics are not grounded in their own lived realities.

Meanwhile, internationalist tendencies in Pakistani rap also connect the movement to the genre’s global epicenters. DirtJaw offers an illustrative case yet again; while rapping in Punjabi is an ethno-political signifier in the Pakistani context, it is also a means to be international. “Punjabi rap is very popular in New York and London,” says Jawad, “and we want to be an international rap group.” Similarly, Rap Engineers, among the founders of Pakistani’s contemporary rap movement, look internationally to introduce new energy to the country’s rap scene. They draw on the American experience, and organize hyped-up rap battles and promote diss culture to invigorate the Pakistani rap scene.

photo credit: Tripod Production Pakistan

Looking inwards and outwards, Pakistani rap is developing not in the shadow of, but in dialectic with its American progenitor. Rap is a growing sub-culture in Pakistan, and “there are thousands more rappers than we know,” says Dar. Describing this multitude in American terms not only shackles our understanding of the movement, it also fails to accurately describe their art.

Their uniquely Pakistani aesthetic reflects Pakistani complexities, and the movement is divided along geographic, class and ethnic lines, each strand reflecting its negotiation with society. Punjabi rappers, many of whom come from the province’s bastion of culture south of its capital of Lahore, reflect their own positionality in Pakistan. They produce a rap deeply attentive to their Punjabi roots. In contrast, rappers out of Pukhtoon dominated Peshawar rhyme sensitive to the global and domestic portrayal of their ethnicity in the War on Terror narrative.

As these rappers grapple with their differing realities within Pakistan, their unique and separate experiences are reflected in their verses and rhymes. Examining this negotiation with ethnicity in their art, the second essay of this series will explore the representation of ethnicity in Pakistani rap.

3 comments