Ajam will be hosting two conversations with Mohammad Salemy this week, and this article is the second in that series. The introduction is authored by Hadi Gharabaghi, while the conversation was conducted by Naveed Mansoori and Mohammad Salemy. Check out the first one here. Salemy is the organizer of Incredible Machines, an academic conference being held in Vancouver this week which examines different aspects of the relationship between technology and the production of knowledge.

In both of Salemy’s conversations, first with Gelare Khoshgozaran regarding the Iran Modern exhibition at the Asia Society and second with Naveed Mansoori about Salemy’s own curatorial debut Encyclonospace Iranica, the problem of identity emerges as the frontline of this contentious debate. This is even more true within the Iranian diaspora which is striving to articulate its apparently fixated and indeed fluid relation within the shifting local and global forces.

The recent popularity of Iranian art has set in motion a proliferation of Iran-related art practices, exhibitions, and discourses. However the missing debate remains as the one that links the genealogy of the term “modern” with the existing cultural policies and campaigns by philanthropic foundations in the United States like the Asia Society and the Iran Modern exhibition. These programs usually serve a number of geopolitical and pedagogical functions mostly by showcasing the democratizing labor of Iranian arts outside of their index of politically threatening nation-state, namely the Islamic Republic of Iran, as they circulate culture between the local Iran and the global West. While the theoretical problem of the local and global has been long exhausted by the globalization of Iranian cultural capital, the radical treatment of this binary in Mohammad Salemy’s curatorial practice through his engagement with Reza Negarestani’s brand of universal and rationalist philosophy is reenergizing the debate about the complex symmetry of the binary’s components.

In these two conversations between Salemy and his counterparts, fashionable concerns about locality, identity and culture are boldly forged out of their comfort zones to face potentialities of the global, universal or general truth via ruminations of Iranianness in art discourse. Curating Iranian art, an indistinguishable discourse from the overall knowledge production about target societies, becomes an occasion to debate the ramifications of global/local binary anew as a form of philosophical concern as an existentially entangled with geopolitical history and aesthetic heritage. Can a diasporic conceptualization of local existence be salvaged through its global pursuit of truth without having to resort to ready-made methodological channels of identity, culture, and history all of which are well burdened with troubling traditions of post-WWII area studies and their orientalist genealogies? If it is possible to raise such a question, it has to be within the bounds of critical art and curatorial discourses and practices. What territory may suit this task better than a continually fetishized endangered specie of the revolutionary and imaginary geography, Iran?

—

Naveed Mansoori: As an Iranian-American and a student of Iranian politics, I am constantly negotiating an identity, severed both geographically and historically, that disorients me from grasping where the inside of Iran ends and the outside begins. I met Mohammad Salemy by chance somewhere on the inside – not in Iran, of course, but that’s the point. I met him on Facebook, that ‘virtual’ inside that has given Iranians within and without the country a radically new way of having a presence in each others’ lives in a fashion that would be unfathomable just two decades ago. Salemy is a Vancouver-based curator and artist from Iran whose current project, Encyclonopedia Iranica, explores how the younger generation of Iranian artists have come to represent themselves and to produce knowledge using digital technologies.

The project, however, is not looking to Iranians who use art as a way of reconnecting with their national, ethnic, cultural, or even historical roots. In fact in a recent online post, Salemy derides the wave of interest in contemporary Iranian art and artists that followed in the wake of the contested 2009 Presidential Elections. His claim is that this wave of interest is fueled by market mechanisms that favor “native” artists who produce “authentic” representations of Iranian history and culture at the cost of overlooking the Iranian diaspora writ-large and the variety of lives and outlooks that exist within it.

Globalization has been the preferred buzz word in the academy, policy circles, and pop culture to capture the rapid changes in world order throughout the past few decades. The notion of diaspora is part of this story, and modern nation-states are still struggling and will keep struggling with the difficulty of gearing policy as if they lived in a world where histories, cultures and societies still remained national in form. For the states, territory is a body that they cannot live without, and for which they will ask their citizens to die if necessary. But people have the gift, and the curse, of mobility, and of rootlessness. In their displacement, be it physical or mental, both by whim and by force, they have contributed to the reordering of the world. They have found themselves with a bloodline and family history with one home, and an “allegiance” and a national history with another. Globalization, however, in having invented technologies to ease the flow of capital has produced a space wherein Iranians, much like other nationalities the world over, can dwell, think, create, share, and debate. We are not slave to the interests of the global market, then; its machines condition our productivity and output, but they do not determine them.

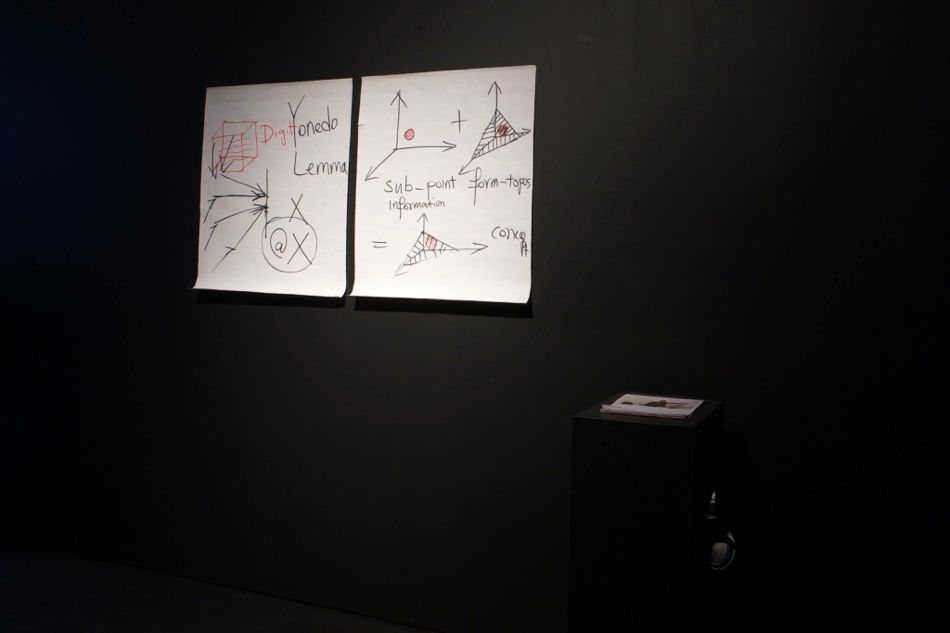

Salemy’s project begins here. The “telecomputational space,” generated by the synthesis between computation and telecommunication, has created a “deterritorial” space, to cite Deleuze, where the categories “local” and “global” bleed into one another, and this not just in relation to geography, history and culture, but to the way we come to know the world as such. The title and theoretical grounding of the exhibition, in fact, takes inspiration from Iranian philosopher Reza Negarestani, perhaps most widely regarded for his “theory-novel” Cyclonopedia, who has written and lectured widely on the nature of knowledge and knowledge-production today. In a short piece written for Salemy’s exhibition catalogue, Negarestani looks to the “universal landscape of truths” as a geography of freedom. In his view, as we navigate our way about this landscape with the compulsion to know the world, rationality becomes a “perpetual struggle that posits itself as a veritable model of freedom,” as it is not bound to physical, biological, and psychological constraints, but with it, we can attain mastery of ourselves with the guidance of reason. In part, this takes a sophisticated grasp of the epistemic spaces that structure our experience of the world with the very technologies that have produced them.

Negarestani’s observations about changes in the structure of knowledge may seem overly abstract and far off from the themes of national identity and diaspora. But Salemy comes to unravel the political consequences of these, if you will, cyclonic transformations to the point at hand. For Negarestani, tele-computation is indirectly instrumental to our navigation through global knowledge systems. Taking this into account, Salemy writes in the preface of the exhibition’s catalogue:

“If technological progress is the externalized continuation of biological evolution in its Lamarckian sense, if the history of technology and human civilization was from the start the story of the separation of things from beings, then telecomputation is the space where the dead and the living, the mechanical and the biological, and, essentially, the technic and the ethnic are cataclysmically fast forwarding to the past and reuniting to start a new natural life.”

Salemy’s claim is that the space of telecomputation has evacuated the category of ethnicity of its traditional meaning, that when Iranians the world over enter into a virtual public sphere as producers and consumers of knowledge, they are unwittingly transforming themselves, the community that they consider their own, and the world with them in the process.

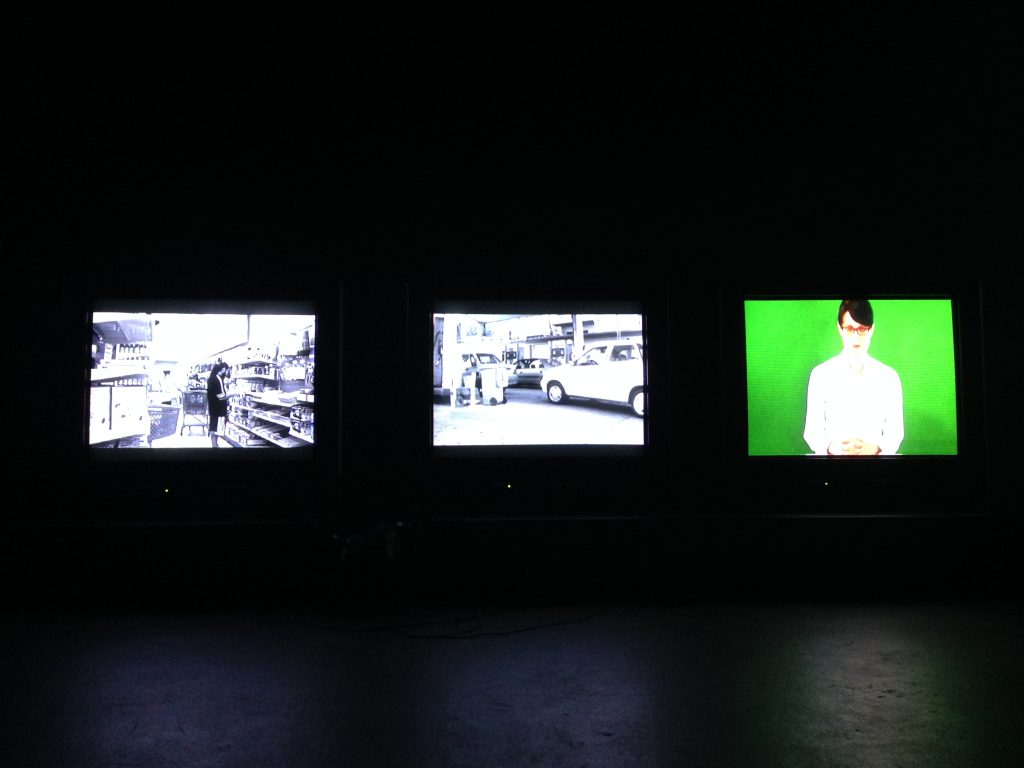

Encyclonoscape Iranica features nine emerging Iranian artists, among them Ali Ahdi, Abbas Akhavan, Ami Ali Ghassemi, Sohrab Kashani, Gelare Khoshgozaran, Tala Madani, Raha Raissnia Anahita Razmi, and Nooshin Rostami, that treat Iran as a point of departure and not a point of return. Salemy, in choosing artists who do not actively partake in the self-reproduction of an authentic Iran, sheds light on, and takes part in, the unraveling of an autochthonous Persian identity. The exhibit is set in a dark room illuminated by the art itself. Each work frames and is in turn framed by its own automated energy. In this way, the exhibit replicates the boundless, homogenous landscape of networked computers.

But rather than take you on a virtual tour of this exhibit by myself, it might be best to have Salemy guide us through this space. It is, in fact, fitting to the exhibit that it be experienced through networked and digital media, with the curator appearing and vanishing, commentating and beholding, among us. So let me now turn to Salemy, and again, by way of the virtual space of Skype, partake in a dialogue that puts under question our geographical, historical and cultural horizons, and bends and contorts, molds and refashions, that common identity that we share.

—

I’d like to move thematically through the exhibition beginning with some questions concerned with identity and subjectivity. Khoshgozaran’s “Speech” is a useful point of entry into this discussion.

The subject’s face in this one channel video is visually split at the center such that the artist’s eyes and an anonymous white female’s mouth are conjoined. Khoshgozaran reads from Lacan’s well-regarded “The Signification of the Phallus,” where he distinguishes between need and desire, while the mouth interrupts to correct the author’s enunciation. If my interpretation is correct the piece is replicating in both form and content the way an impossible desire for fulfillment becomes entangled with an impossible desire to be like the ‘they.’ For Khoshgozaran, race and gender are visible and indelible identities that can be interrupted but not effaced in the register of language.

But juxtapose Khoshgozaran’s piece to Kashani’s stop-motion picture where he draws out the ‘heroic’ from the mundane by self-depicting himself as a superhero doing everyday household chores.

In this piece, the ultimate contingency of time, in the ‘stop-motion,’ leaves each ‘iteration’ of our identities open to transformation but any ‘intersectional’ relation is literally ‘molded’ into a single figurine. Kashani’s protagonist finds redemption in the temporal representation of the medium; Khoshgozoran’s protagonist in the split configuration of her face. Your exhibit seems to be negotiating a similar impasse in regards especially to the referent “Iranian.”

In the exhibition’s catalog, you refer to the artists, and even maybe Negarestani, as “Iranians” who use this identity as a platform from which to self-represent. But I wonder to what extent you present these identities as ‘self-referential,’ and perhaps invisible, and to what extent it is something that is inscribed on our bodies.

Mohammad Salemy: Not surprisingly, the tough nut to crack here actually doesn’t have a hard shell. Identity, be it historical, ethnic, cultural or even professional is as much a changing camouflage as an identifier. The inscription really is in the eyes of the beholder, or in the case of Khoshgozaran’s American friend, in her mouth.

My way of understanding Khoshgozaran’s Speech is to see it as the denunciation of formalism. In her piece, the point of the conversation is missed because the friend keeps insisting on the proper form of its delivery. While the “Iranian” woman in the video is concerned with the universal application of Lacan’s theory, the American counterpart is literally lost in obsessing over its correct pronunciation. Considering how these two faces form a univocal ontology, there is a tension between form and content or on the one hand the authoritative voice that constantly inscribes ethnicity on the speaker, and the other hand Khoshgozaran who fulfills the correcting orders only to get a chance to move on with her task of spreading knowledge. The work literally portrays an internal scuffle within a singular subjectivity.

What really defies the dichotomous nature of identity in this work is the integration of the two half faces into one in spite of the ever-presence of a visual horizontal line that cuts through the frame. The emerging face also identifies the Simondonian process of individuation in which the social production of the self creates a third other which is neither the individual nor the society. After watching the video several times, I now have the image of a non-existent third person etched in my mind as if she really exists.

So I think the pressures to either have an identity, or to reject cultural or ethnic associations and be generic, like other dialectics, creates surprising syntheses, which, in the long run, will move slowly away from the particular towards the universal in all directions. Like with this video, universality will not result from antagonism but from both sides, confronting something that emanates out of a different dimension. There is this great quote by Michael Ferrer which both Negarestani and I have reposted as a status update on Facebook: “The basis for a universal ethics will not be reached through negotiation between different, competing cultural traditions, but under the conditions set by a demand that those traditions relinquish their claims to superiority in the face of a knowledge which evaporates the differences between them.”

N: I suppose I was wondering how/if that would bear on Kashani’s piece as it’s about retrieving the heroic in the everyday. Someone like Dabashi, I imagine, would see the crowds that spilled into the streets in 2009 as bearing a “collective identity”. He called the Tehran riots a “civil rights movement,” but that could be seen as problematically obscuring the question of non-identity that is so important to Khoshgozaran. I understand the work that Khoshgozaran’s piece is doing — but I wonder when Kashani’s heroic subject enters into the picture, if at all — is Kashani’s protagonist that “third person” you envision now when thinking back to Khoshgozaran’s piece, or should we be wearier of these aesthetic reductions?

M: I warn you! We can talk about these works all we want but I believe we will be doing them more service by mapping out what is at stake conceptually in terms of the new rationalist project’s critiques of neoliberalism, Marxism and cybernetics. But since you brought this up, I need to respond, at least to this case.

I think Khoshgozaran’s plea is for the partner in the conversation to get over the accent and hear the universal, also a desire for a hyperuniversal feminism that is neither blind to the specificity of non-white women nor is it constantly meandering in the historicist and culturalist specificities of the subaltern. Dabashi’s application of his notion of “post-Orientalism” to current affairs like the Iranian uprising of 2009 and the Arab spring is really a different kind of universalism; that of post-global petite bourgeois subjectivity of late-capitalism. I feel that his advocacy of cosmopolitanism is a way of saying that the Orient was ahead of the West in embracing the gilded age of the city-states and a “world trade” style laissez-faire. But since stating this is actually taboo in the academia, it needs to be veiled in jargon. The perverse and murky side of Dabashi’s cosmopolitanism is clear in Simon Critchley’s newly published story, “Moscow, January 1, 2019,” in which large corporations abandon nation-states and form their own coalition of big cities called “cosmos,” or “the league of rootless cosmopolitans,” issuing their own passports with their own police force and border agents.

In regards to Kashani, I think his piece, for one, is a balance between the problems of being an emerging artist in Iran in particular, and, secondly, of being an artist, in general. Kashani’s video touches upon the general/particular identity, in my opinion, of the emerging artist within the art world.

N: I’d like to turn to consider how some of these pieces relate to contemporary literature by geographers, most notably David Harvey and the late Neil Smith who are spurred by a demand imposed on us to understand the spatial injustices that divide the social world. Two of the pieces in the exhibition, in particular, negotiate how urban spaces structure and are in turn structured by us, both in the everyday, and as producers and consumers of their depiction.

Raissnia’s “Chaleh Harz” synthesizes cinema with older technologies to depict a neighborhood in Northern Tehran known to have an economically underprivileged population.

In Anahita Razmi’s Tehrangeles, three video monitors depict both Tehran and Los Angeles with real and fictional material. A book supplements the videos in which the names of each city in news articles have been replaced with “Tehrangeles,” emphasizing the “flattening” of the world and a common ground for politics in the global space of capital.

A piece like “Chaleh Harz” seems to haunt the potential for a cosmopolitan utopia in Tehrangeles, however. For as ‘flat’ as the world may seem, there are places like Chaleh Harz that force us to consider local places. Not only within Razmi’s “Tehrangeles,” but also within Negarestani’s “global landscape of knowledge,” we must reckon with the fact that people are rooted to the land. When we refer to ourselves as “Iranian,” are we not always referring to that “territory” “over there?” Is this place-based reference imposed upon us insofar as the state has ownership of that land? To what extent will digital media allow us to negotiate our local existences, in Vancouver, in Los Angeles, in Paris, etc. with these “deterritorial” spaces?

M: The spatial problem of life on earth is like a geometric enigma in which “close” is always too close and “far” is never far enough. Earth seemed boundless before we could see further than the human scale, and before we knew what really lay before our eyes. Technology has finally made the depressing fact known that the earth is nothing but a small sinking island that we have failed care for with our “worldly” knowledge. The kernel of truth for realists and materialists is that we are all prisoners twice over, of the earth, and of the world we have created. The rootedness we are advised to cherish by certain “philosophers of the world” and those advocating identities alike should be exposed as a form of Stockholm syndrome. Even if attachment to the earth is eternal – which I really don’t think it is – there is nothing to be gained from restating the obvious, or worse restating the conditions of our captivity.

One of the strengths of Negarestani’s philosophy, which can also be traced in the works of Ray Brassier and François Laruelle, is that he shows how in the absence of any viable technology for jail-breaking the prison house of our planet, the only liberating potential rests in our ability to think creatively beyond the limitations imposed on human thought by the empirical world. Conceptual thinking or philosophy is the only practical spacecraft that can dislodge humans from material constraints, enabling them to move freely in the global space of knowledge where reality, which is always local and earthbound, normally forecloses the horizon of truth.

In this regard, to me, Raissnia’s Chaleh Harz begins where Razmi’s A Tale of Tehrangeles ends. In Razmi’s world, the seemingly fundamental differences of the two contrasting urbanities of Los Angeles and Tehran are collapsed into a single plane of mundane city life; and the two localities are portrayed as near and almost indistinguishable from each other. Her book also uses news headlines to further show the indiscernibility of these seemingly opposing cultures. Chaleh Harz bleeds into this picture right here and offers a way out of the homogeneity of the “shrinking” earth, which is a much more accurate metaphor of where we are globally in comparison to the Freidmanian “flatness” that falsely celebrates the inadvertent triumph of democracy and the emergence of an equal playing field for all of humanity. There are moments in Chaleh Harz that a face or a body emerges out of the movement of abstract black-and-white forms. However, soon the face gives way to the chaos and movement of non-representational and moving shapes on the screen.

Abstraction which is the erasure of recognizable imagery in this instance corresponds to Negarestani’s opening passage in the text he wrote for the exhibition’s catalogue: “Traditionally, philosophy is an ascetic cognitive experimentation in abstract (general) intelligence. In the broadest sense, it is simultaneously a rigorous program of abstraction and a platform for automation of discursive practices whose mission is to arrive at what came to be known to Greeks as logoi or truths.” I interpret this as a beautiful binary that the author sets up between local/reality/world and global/truth/abstraction. So contrary to those who think of robust technological interfaces or new forms of data visualizations as the aesthetics of accelerationism, I tend to see pure abstraction, the kind emerging in Raissnia’s work as the way forward, a kind of abstraction that has a foot in the real world but strives to show the arbitrariness of forms we understand as the complete containers of worldly meaning.

N: David Harvey actually recently addresses this issue in Cosmopolitanism and the Geography of Freedom, where he touches upon a debate among some scholars of Kant as to whether the finitude of the earth was a justification or a circumstance for cosmopolitan right. Harvey himself, of course, will say that it’s a circumstance, and then sets out to offer a materialist conception of geographical knowledge — and ultimately, as he mentions elsewhere, he advocates a ‘militant particularism’ by which we come to know and understand the specificities of this time, and this place, in order to act strategically in opposition to global capital. I find that Harvey, however, does not have much to say about identity and subjectivity — of “mediated” phenomenology, of the kind that a feminist that Linda Martin-Alcoff develops, or again, as Khoshgozaran’s piece is so concerned with. It seems to me that for Negarestani we don’t have to concern ourselves with questions of culture, identity, subjectivity, when we have philosophy at our disposal. Someone like Harvey, and perhaps Negarestani, doesn’t seem to account for the experience of life in Chaleh Harz — but only to suggest, and to this I wouldn’t disagree, that an exit is possible and actually available.

M: We would be lying if we pretend these two dilemmas are easy to resolve: the one between identities and the universal, or as Laruelle puts it between “indentity” and Identity, or more precisely indenticality. This tension is also very similar to the one between politics/culture and philosophy. When simplified and seen from the perspective of pure philosophy, they can be viewed dialectically, between past and future, and between necessity and contingency. How do we account for the concreteness of history without rewriting the future with the ink of uncertainties, and how do we account for the future if our historical modality reminisce the Benjamin’s angel with its back facing the future, powerlessly thrust forward by the wind of capitalist progress. For me, this angel badly needs a kick in the ass as a way of becoming aware of the fact that one can do more than just worrying about the catastrophic past. The wind of progress, even if we agree that is propelled by a capitalist conspiracy, can be navigated more prudently than the way Benjamin prescribes it. As you said, though, what matters at the end of the day is that there is a practical hope for an exit from Chaleh Harz, which, whether we like it or not, must pass through the revolving turbines of technology.

N: Let’s turn briefly to your dialogue with “accelerationists,” like Alex Williams and Nick Srnicek, who assert, very simply put, that instead of smashing the technologies of global capitalism that exploit us we must learn how to use them in order to defeat capital at its own game. In addition to Raissnia’s piece, as you claim, “opening the door to a truly accelerationist aesthetic,” and mismatching digital technologies to produce an abstract image that didn’t oblige itself to conceiving advanced technologies as reproducing “reality,” Rostami’s mobile sculpture created from a water-damaged iPhone might also figure in the “accelerationist” narrative.

I recall a story I read recently about Ethiopian kids who were given Motorola Zoom PCs and within 5 months had hacked into them. Here is perhaps a movement, as in Rostami’s sculpture, from the mechanical to the machinic, from a device that is organizationally closed, to one that is structurally open. We can also look to the last few decades of Iran’s history to capture this movement: from Khomeini distributing his sermons with cassettes from abroad; the clerical schools in Qom admitting the Internet into their curricula to ‘spread the words of the Prophet;’ the emergence of the Persian blogosphere; and the incredible use of Facebook, Twitter and YouTube during the green movement riots in 2009.

I’m still left wondering if your exhibition is capturing a moment, or some moments, of an ‘accelerated’ history; if it’s partaking in the acceleration of history; or if it’s doing something altogether different – like, to provoke a bit, ‘retrieving the agency’ of underrepresented Iranians, discovering the creative in the productive, but potentially becoming a bid for cultural self-determination.

M: About Rostami’s work, I completely agree. Capitalism’s vulgar embrace of speed is in no way indicative of the dominant economic system’s real commitment to moving forward.

Rostami’s mobile sculpture decelerates the time of mobile telecommunication by auto projecting its slowly drifting shadow on the black wall. This suggests that often in order to move faster in the global field of knowledge, you need to slow down the transmission of worldly data in the local and empirical field. The piece can also be seen as an example of how one can dismantle and salvage elements of neoliberalism towards genuine postcapitalist solutions.

Rostami’s piece also highlights the significance of the intentional activities of humans. From the 19th century and on, there has been an attempt to remove any sign of human touch in design. From very early on, corporations wanted to pretend that their products were created through automation and by machines only. This trend has only gotten worse. With computers and mobile devices we get an object that looks like it was even designed by machines. Rostami negates this tendency by reconfiguring the iPhone into a handmade piece, suggesting that, for the better or worse, humans have a major role in reversing capitalism.

N: That much I understand — that there is poetry in reconfiguring the elements of the world you dwell in. But how do you see the artists in your exhibit, as sharing a common Persian identity, avoiding the reification of identity by working together in one space, on one project. I mean this less as a critique and more as a curiosity about how identity can be used strategically, or can become a basis for artistic production, and how that figures into the broader accelerationist narrative.

M: The way I saw these artists coming together was how your friends’ posts lineup on your Facebook wall or Twitter feed, not completely arbitrary because after all you added those people and they decide to post things at a certain time, but also arbitrary because the posts are not always aware of each other and get programmed on your wall by an algorithmic logic external to that of your friend’s posts. I think this kind of organization even though wears its mechanicality on its sleeve ends up creating more interesting contingencies that the tightly programmatic kind of curation that feeds the global contemporary art world these days.

N: In Iran, we have a tradition of geography, so to speak, with Ahmad Fardid who coined the term gharbzadegi (westoxification) and Jalal al-Ahmad and Ali Shariati who were responding to this provocation in different degrees, in order to identify the forces threatening authentic Iranian culture. Shariati repeats time and time again, of course, that we must look to geography – that it “speaks more truthfully than history” – and I would argue that he is trying to identify the enemy of Iranian culture by building narrative structures in the form of geography.

But these thinkers, for the most part, correlate or even conflate social geographies with cognitive ones, overlooking the simple fact that even in a groundless and disenchanted world, we still walk on soil, and the state continues to have a claim over our bodies and the land we stand on. Aren’t we obliged to retain a serious concern for ‘that’ territory ‘over there,’ in this regard, even if our technologies have liberated us from our rootedness in the earth? And moreover, do you see your exhibition as free from reference to the “homeland,” so to speak, or are we forced to constantly refer back to that really existing place when we speak and act as members of an Iranian community?

M: The concept of cultural toxification is itself a Western concept. Before becoming the obsession of Iranian thinkers and intellectuals, the idea of a pure culture which can be perfectly protected from foreign influence belonged to Western intellectuals. For example, in Parallax View, Zizek writes about an Italian traveler named N. Bisani who visited Istanbul in 1877 and was disgusted by the sight of cultural hybridization taking place in the Ottoman Empire:

“A stranger, who has beheld the intolerance of London and Paris, must be much surprised to see a church here between a mosque and a synagogue, and a dervish by the side of a capuchin friar. I know not how this government can have admitted into its bosom religions so opposite to its own. It must be from degeneracy of Mohammedanism, that this happy contrast can be produced. What is still more astonishing, is to find that this spirit of toleration is generally prevalent among the people; for here you see Turks, Jews, Catholics, Armenians, Greeks, and Protestants conversing together, on subjects of business or pleasure, with as much harmony and good will as if they were of the same country and religion.”

Fardid and Shariati were educated abroad and coincidentally both studied with Henry Corbin who celebrated a pure form of Shi’a culture. These intellectuals unknowingly reversed the direction of the Western concept of uncorrupted culture. The advocacy of the return to one’s self also ended up camouflaging the western roots of so many of their other contributions. I don’t know if you have noticed ever that the words “interpretation” and “hypocrisy”, tafsir and tazvir, rhyme in Farsi. So in a way one can use Shariati’s “return to one’s self” to get to the existentialist roots of his thought, or Fardid’s gharbzadegi as a camouflage for his devotion to Heidegger’s anti-modern project. Sadly, whether they knew or were willing to admit, it seems that what these authors disliked the most about the West was the embrace of hybridity, which can be argued that western civilization had acquired via interactions with the “Oriental East.”

My project defies its own territory through starting as an exhibition about Iranian art only by arriving, through movement, to the idea that there isn’t anything concrete or tangible about the Iranian identity that can be grasped or schematized in contemporary art. Hence the reference to “encyclopedia” in the title of the show – a reminder that any honest approach to the practices of Iranian artists can only be “encyclopedic,” meaning a kind of themeless and A to Z or here-is-a-list-of-people approach.

—

Naveed Mansoori is a third-year graduate student at UCLA in the Department of Political Science. He is interested in the history of political thought, specifically in the context of modern Iranian history. Mansoori’s most recent project considered Ali Shariati’s well-known lecture, “Bazgasht be Khishtan,” with attention to his “science” of Islam.

Mohammad Salemy is an independent Vancouver-based critic and curator from Iran. He has curated exhibitions at the Koerner Gallery and AMS Gallery at the University of British Columbia, as well as the Satellite Gallery and Dadabase. He co-curated Faces exhibition at the Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery.

Hadi Gharabaghi is a PhD Candidate in the Department of Cinema Studies at New York University. Hadi’s dissertation examines the genealogy behind a network of academic, philanthropic, and government investment in fostering film cultures as means of liberal pedagogy within a diplomatic history of applying humanism as an instrument of foreign policy.

1 comment