A guest post from Sepehr Vakil and Shirin Vossoughi.

Sepehr Vakil is a doctoral candidate at the University of California, Berkeley’s Graduate School of Education. His research interests include the sociopolitical and cultural context of engineering and computing education, intersections between youth activism and digital media literacies, and issues of race, equity, and learning in urban schools. Follow Sepehr on Twitter @zarbesepehr.

Shirin Vossoughi is an assistant professor at Northwestern University’s School of Education and Social Policy, where she draws on ethnographic methods to study the social, cultural, historical, and political dimensions of learning. She takes a collaborative approach to research, partnering with teachers and students to study the conditions that foster educational dignity and possibility.

As Iranians who have spent most of our lives living in the United States, and as educators and scholars working alongside students and teachers of color, we have been engaged in an ongoing conversation about race and solidarity in the U.S. context. In particular, we have thought together about our role as Iranians in relation to struggles for educational equity and movements for racial justice, such as the recent organized response of Black communities and allies to the murder of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri.

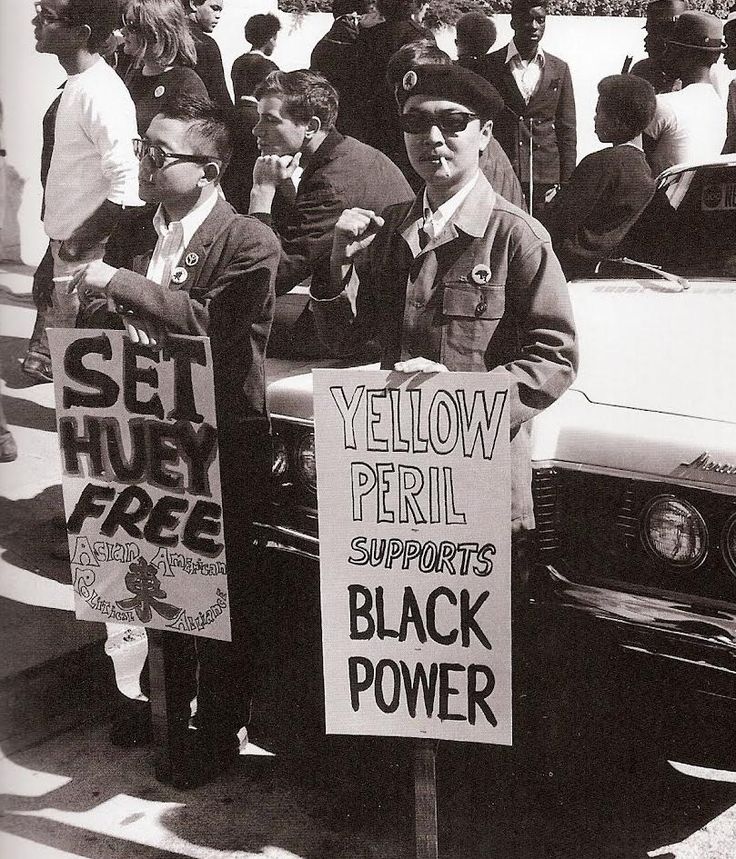

As educators, we are inspired by the ways Black youth, women and queer folks are at the forefront of this growing movement, and by the critical questions they are raising with regards to the meaning of leadership and resistance. We also acknowledge the traditions that have preceded these events; the fundamental intellectual and political contributions developed through generations of struggle in the Civil Rights, Third World and Black Liberation movements. Indeed, many of the historical debates that emerged within these movements are reflected in the conversations and tensions around the term “Black Lives Matter.”

Our reflections on solidarity therefore begin with the recognition that the injustices we are witnessing trace back to the founding of this nation, and to the sustained and myriad forms of resistance led by African and Indigenous peoples across the continent. It is against this backdrop that we hope to examine the ways we, as a community, participate in anti-black racism, and how we might contend with both the hierarchies and potentials for solidarity that emerge within liberatory movements. That is, we recognize that solidarity work is hard work, and that unity does not come without struggle.

The Personal and the Political

We enter this conversation with some questions: What do the identities and labels we wrestle with in our everyday lives (Irooni, Iranian-American, Persian, Middle-Eastern, Muslim, White, Brown, Mixed, People of Color…) mean for how we do or do not identify with and support the struggles of other communities of color, particularly the growing movement against police brutality and mass incarceration? What does solidarity mean in this context, and what kinds of tensions and possibilities might it raise?

These questions are both intellectual and personal. In our case, we were raised in political households where issues of social justice were everyday dinner table conversations. Our parents and relatives were consumed with the news of their homeland, deeply concerned with the plight of political prisoners, jailed journalists, and family members struggling with the daily stress and struggle of life in Iran. As children, we were listening closely and learning to think about the world while struggling to navigate life in Amrika: being othered as outsiders by classmates, trying to figure out what it meant to be associated with this place called “Eye-ran,” learning from school and the broader culture to be embarrassed of our parents’ immigrant-ness, and living with the constant fear of an impending war with the country where our grandparents and relatives live. As we got older, these experiences became portals to connect with the experiences of other young people of color. In fact, adopting our family’s political commitments often translated into recognizing forms of injustice and oppression in the U.S.

Yet, these worlds often seemed disconnected; our own experiences of alienation and discrimination, as well as the racial hierarchies we were learning to participate and locate ourselves within, did not often find voice at the dinner table. These are some of the silences we wish to contemplate. Perhaps our parents, because of their profound sense of loss and the weight of their direct experiences with displacement and political upheaval, struggled to relate to their children’s encounters with discrimination, or outwardly acknowledge episodes of their own marginalization in the U.S. As young people, the education we would come to receive through ethnic studies courses, student and community organizations and conversations with elders and peers allowed us to recognize these episodes as everyday manifestations of the very political and economic policies our parents struggled against in Iran—many of which were rooted in the assumption of Western superiority.

We speak from our own experiences and do not presume these to be shared among Iranians in the U.S. At the same time, we are interested in what a broader dialogue about racial identity and solidarity among Iranians from a range of backgrounds and generations might look like. Building on existing histories of Afro-Iranian solidarity in the U.S., and the public and private spaces within which these conversations are already taking place, we also wish to consider the spaces within which they could take place. We hope to spark dialogue with fellow members of our community who may be grappling with similar issues and collectively generate resources for how to open up or expand these conversations within our families, cultural spaces, religious centers and community organizations. In this effort, we draw from the work of scholars, educators and organizers addressing the complexities and urgency of solidarity in these times.[1]

We write this essay out of love. We are all too aware of the racist and orientalist portrayals of Iranians, and recognize that even well-intentioned critiques in a time when little positive is said about our people may be unwelcome. But love for our community also means challenging the relative quiet we have observed in response to the recent and ongoing displays of racialized state violence against Black people in the United States. These are also some of the silences we wish to contemplate.

Solidarity

As educators and researchers, much of our own work deals with understanding the structures of power that marginalize Black, Brown, poor and immigrant youth, as well as developing and studying alternative educational possibilities that could be both personally and politically liberating. We work with youth who are confronted daily with staggering obstacles, whose communities and schools are so underfunded and maligned, that to speak of educational achievement without engaging the sociohistorical and political context of students’ lives (and without questioning the official school curriculum) is itself an act of violence. These obstacles do not just make it difficult to perform in school. They also are obstacles to living. To breathing. That is, they include the threat of being murdered, while unarmed, while eating Skittles, or walking home with a friend, or playing with a toy gun, or riding public transportation back from a New Years party.

So, we also write this essay out of love for the students we work with and the communities they are a part of, and out of an understanding that Michael Brown, Eric Garner, Tamir Rice, Trayvon Martin, Rekia Boyd, Oscar Grant, Yvette Smith, Jordan Davis and so many others are tragic examples of a larger pattern of systemic state violence against poor people and people of color in this country.

But what is “solidarity”? Is it a stance, an action, a way of thinking and feeling? What does solidarity with Black and Brown people as Iranian people look like? How can we work to identify our own cultural identities (plural) as Iranians, our own political histories, traumas and struggles for self-determination as resources to draw upon as we build bridges and alliances with other racialized communities? How do we also recognize and wrestle with our privilege relative to many poor communities of color? These are questions without easy answers; they require our collective dialogue and reflection.

Questions of Privilege and Whiteness

From our perspective, such reflection requires naming and contending with our own participation in racism. We might ask: where do our complicities and interests lie? Broadly, the act of migrating and living in the U.S. implicates us in the settler-colonial project, as does our participation in a political and economic system built on racial categories. More specifically, Iranians have struggled with and sometimes against the bargain of “honorary whiteness,” whereby active dis-identification with Black and Brown communities serves as a ticket to participate in the spoils and privileges of whiteness. 9/11 and the overt surveillance and criminalization of Muslim and Middle Eastern communities shook many out of the fantasy of what Linda Sarsour (Executive Director of the Arab American Association of New York) calls “artificial white privilege.” Yet our continued participation in narratives that position Iranians as a uniquely successful immigrant community both thwart possibilities for solidarity, and erase the economic, social and racial hierarchies within our own community. Drawing from critiques of the model minority myth within Asian American communities, we recognize that when our worth as a community is equated with economic, educational and professional successes (and when these successes are explicitly or implicitly rooted in cultural superiority), we participate in masking the relative privileges of access and opportunity that often made those successes possible, ignore those who are marginalized within our own community, and contribute to bolstering the myth of American meritocracy.

These are difficult conversations. Naming anti-Black racism or confronting our own internalized racism inevitably stirs up strong emotions, including anger, guilt, and fear. But this work is critical both to the social and political development of our own community, and to opening up avenues for solidarity with other communities of color in the U.S. In fact, these two projects, the work of developing a political clarity around our own position in American society, and the work of finding ways to stand in solidarity with other communities, are deeply interwoven. Honest conversations about internalized racism among Iranians might explore how assimilating into a Eurocentric culture is connected to practices such as Anglicizing our names, straightening our hair, surgically altering our noses, choosing to join in rather than resist racist depictions of Islam or Muslims, or even insisting we are “Persian” instead of “Iranian.” Some of these practices may serve as a shield against racism; but they also leave White supremacy in tact. While they are directed inward, at ourselves and towards our own people, the other side of the coin is directed outwards at other people of color, often of darker complexion, whose lower social positioning in a racialized U.S. context provides rationale for tired narratives of Iranian cultural superiority.

Anti-Black racism therefore emerges in both overt and covert ways. While the term “racism” may be associated with explicit forms of discrimination and hatred, it is imperative to recognize the ideologies circulating in the air we breathe and examine the ways they shape our everyday assumptions, fears, attitudes, beliefs and desires. As educators, we are particularly aware of the ways notions of cultural superiority require and are bolstered by assumptions of cultural deficiency among Black and Brown communities. To do the work of decoupling this binary, we might ask ourselves: Where do our definitions of beauty, intelligence and humanity come from? How can they be deconstructed, redefined, transformed? We believe that however complex and messy these conversations can be, they can help us understand our individual and collective struggles as resulting from an ideological and geopolitical context that positions us tenuously within a racialized order, and generate new insights and tools for self-love and community pride that are rooted in solidarity rather than hierarchy.

Making Connections

While the work of challenging anti-Black racism in our own families and communities may therefore draw from critical discussions about what it means to be an ally (including the need to learn from rather than take the lead on struggles we may not personally experience), we also need not rely on white models of allyship. In fact, dis-identification with whiteness can illuminate points of connection, respective nuances and shared histories of anti-colonial struggle. Thus, a second and equally important dimension of this dialogue involves naming and actively making connections between the histories and experiences of people from our part of the world and those of other communities of color. The parallels are too numerous to adequately address in one essay: the impunity of state-sanctioned violence in places like Afghanistan, Yemen, and Palestine, drone warfare and the a priori guilt of young men, the active dehumanization that justifies economic sanctions, torture and imprisonment and makes “due process” a luxury, the expectation that “good” members of the community denounce the actions of the “bad,” and the strategic criminalization of protest and dissent—all undergirded by an official narrative that masks its crimes by treating violence as a property of the oppressed. Importantly, drawing these connections may also create the space to confront hierarchies and points of tension between and among Iranian, Arab and Muslim communities.

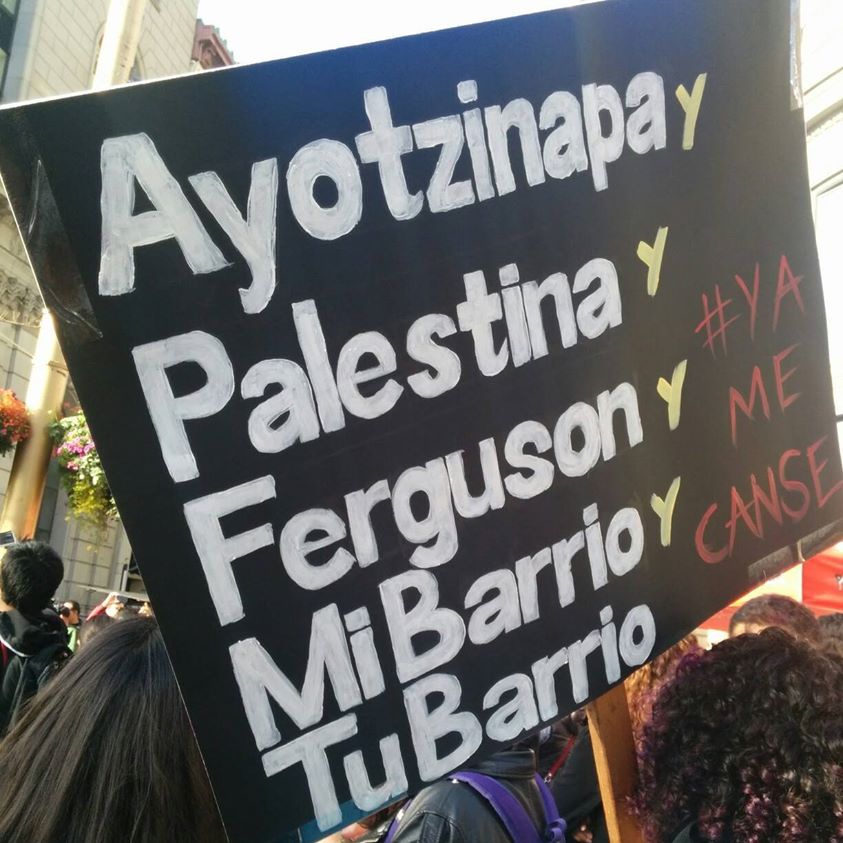

These conversations can surface new analytic and political possibilities: what might it offer to read police brutality in the U.S. through the lens of political repression (as seen, for example, in the parallels drawn between Ferguson and the murder of students in Ayotzinapa, Mexico)? How do culture-of-poverty discourses in the U.S. context mirror orientalist strands of modernization theory? What does it mean that young people in places like Palestine have drawn from the kinds of civil disobedience central to the Civil Rights Movement and offered tactical support to protesters in Ferguson? Such questions can move us towards a sharper understanding of global structures of power, help identify new resources for creative political action, and nurture a bi-directional solidarity that emboldens Iranians to stand behind and with Black communities in their centuries-long struggle for freedom on U.S. soil, while imploring all of us to stand against the expansion of U.S. military power, economic sanctions and occupation in the Middle East.

Individual and Collective Change

The Iranian diaspora community is relatively young, and we are proud to learn from and work among a generation of scholars, educators, artists and organizers pushing the envelope on questions of race, class, gender, sexuality, religion, education and politics. Yet we also feel the need to address the specificity and predominance of anti-Black racism, to work together to identify the untapped potentials for dialogue, learning and solidarity.

Collective change requires new opportunities to speak and listen to one another’s experiences, ideas and questions with regards to both the current movement against police violence and broader issues of race and identity. These conversations go hand in hand with negotiating and reimagining what it means to be Iranian in spaces such as our Farsi classes, social and political events, cultural and community centers and family gatherings. As educators, we understand the particular importance of helping young people in our community navigate the messages they receive; Iranian youth are simultaneously marked as different and less than and positioned to either participate in or work to transform long-standing social hierarchies. We also recognize the myriad, creative ways the next generation of Iranian youth growing up in the U.S. are exploring these questions and pushing us to think more deeply. As they learn from and teach us about how to think about the world, we hope to carry forward and do justice to the personal and political lessons our parents and grandparents taught us and collectively nurture a strong sense of solidarity, the fruits of which we have yet to see.

[1] See for example:We Choose Resistance: National Call on Black and Asian Solidarity

Call Out for Solidarity With Black Relatives: An Open Letter to Brown and Red

Southeast Asian Activists Urge Solidarity with Black People Post Garner Non-Indictment

US Police Brutality Protests Hit Home With Palestinian Prisoners

The Secret History of South Asian and African American Solidarity

5 comments

Contrived. How utterly tedious and facile to reflect upon this burning subject from the angle of being an Iranian in the USA. Pseudo-academic words. Just words. But, like the buzzing of a fly, annoying, because of the immature flimsiness of the argument and the opportunistic, inoperant and gauche caviar references to US hegemony. There is no doubt that stupid US foreign policy is to blame for the Iranian revolution, and the creation of a diaspora, but thus drawing lines between imaginary dots is at best not convincing and at worst, pathetic. Hopefully the authors will be able to find more useful ways of displaying their academic credentials. This article is a waste of time for any informed reader and a waste of effort for the authors.

Hi folks!

Thank you for writing this.

I had one comment, as a reminder, there are Afro-Iranian and Black Iranians in Iran too! Let’s not forget them, not all Iranians are Brown or white-passing…so the collective “we” is even more intersectional.