This article is by guest contributor, Kat Thornton. Kat is a masters candidate in Journalism and Near Eastern Studies at NYU focusing on 19th and 20th century Persian poetry.

“Of course, as I work on these poems, I don’t have the Persian to consult. I literally have nothing to be faithful to, except what the scholars give.”

—Coleman Barks, Rumi: Soul Fury, 217

“You should have seen it. There was this guy, he walked up to the front of the room—I swear, you would never expect this guy to read Rumi,” said my best friend’s mom, who is from northern Iran and now lives in Idaho. She was telling me about a “Rumi Night” held by the Boise Public Library a few months ago.

“He had a big belt buckle—he was like a cowboy. And then he told everyone that reading Rumi changed his life,” she told me with a big grin. She was amazed that Rumi had reached an audience in the Northwest United States. I had to wonder which translations they were reading.

If you’ve read Muhammad Jalal al-Din Balkhi, most commonly known as Rumi in the U.S., in an English translation, the chances are that it was translated by Coleman Barks. While most literary translators don’t exactly gain international fame, Coleman Barks has headlined numerous festivals and poetry readings and taken official trips to Afghanistan and Iran. He was granted an honorary degree from the University of Tehran, all for his 30 years of work on the poems of Rumi. A poet and professor from Tennessee who taught at the University of Georgia, Barks calls his publications “versions,” or “re-renderings” because he doesn’t read Persian.

The mass appeal of Rumi can be attributed to these types of popular translations. Over 500,000 copies of Barks’s books have been sold, in the English-language market where a book of poetry rarely sells more than 10,000 copies. Rumi quotes can be seen circulating on Facebook, in tattoos, and memes.

Barks claims that his versions of Rumi are more appealing to a modern audience because they come closer to the “essence” of Rumi. But is this essence Rumi or is it Barks seeing modern, pick-and-choose spirituality in Rumi’s verses? Barks, suffering from a particularly profitable case of researcher’s blindness, has flooded the market with a Rumi that has come to symbolize the individual beholden to no particular tradition, a man who seeks love before God or faith, all too familiar already in the canon of English, specifically American, literature. “Rumi” became the best-selling poet in the U.S. in the 1990s, but it is an essentialized version of Rumi, made for the tastes of a mainstream audience looking for a quick spiritual fix. The result is a New Age poet, devoid of Islam, the 13th century, or the themes and images of the golden age of classical Persian poetry.

Barks’s work is difficult to criticize because he sets his stakes low. He makes it clear in introductions to the text that he does not know Persian. “My collaborative versions of Rumi have no status in the scholarly world,” Barks wrote in his introduction to Rumi: Bridge to the Soul. But on book covers, event flyers, and in the media, Barks is advertised and considered by many to be the man who introduced Rumi to the West. Several translators have made brief criticisms of Barks in introductions to their own translations, but despite the influence of Barks on the informal study of Rumi, there are few critical examinations of his work in English or in Persian.

What Barks translates isn’t not Rumi; he is not fabricating translations, as has been the case for several popular “inspired” translations of classical Persian poets like Hafez and Khayyam. Barks’s translations can be categorized as “secondary translations,” meaning they are re-renderings of primary translations from the original texts. In doing so, Barks says that he appeals to a less academic, more emotional analysis of Rumi. But an academic approach is not necessarily in opposition to a sentiment-based interpretation of Rumi. In writing his baseless translations, Barks frees himself from the constraint of Rumi’s actual lines, while allowing himself to profit from Rumi’s name.

As the story goes, Barks started translating Rumi when in 1976 his mentor, poet and translator Robert Bly, handed him a copy of translations by A. J. Arberry and told him, “these poems need to be released from their cages.[2]” Before this, Barks had never heard of Rumi. His story ever since is one of coincidental encounter. He began re-rendering Arberry’s verses informally after teaching poetry classes. Not long thereafter, Barks says he had a dream in which he saw a Sufi teacher who told him to continue with his work. Two years after beginning his re-rendering, he was introduced in person to the teacher he saw earlier in the dream. His name was Bawa Muhaiyaddeen and he was a Sri Lankan sufi living and teaching in Philadelphia. Barks credits his understanding of Sufism and the mysticism in Rumi’s poetry to his visits with this man, which occurred 4-5 times a year until Muhaiyaddeen’s death in 1986. Some have compared Barks’ relationship with Muhaiyaddeen to that between Rumi and Shams-e Tabrizi, an ambiguous relationship of student-teacher or lover-beloved. Barks attributes his entire understanding of Rumi and Sufism to his interactions with Muhayhaddeen. Barks would later work with John Moyne, head of the department of linguistics at the City University of New York, on re-renderings of his literal translations of Rumi. Since then he has published versions based on unpublished Moyne translations as well as Arberry and Nicholson translations, and other primary translations.

In his history of American spirituality, Restless Souls, Leigh Eric Schmidt places Barks inside a narrative that includes the protestants, the transcendentalists, and Oprah. Schmidt characterizes the success of Barks’s publications as attributable less to Rumi than to a nineteenth-century poet: “Rumi refracted through Walt Whitman—that is how the Tennessee-reared, Berkeley-trained poet Coleman Barks has made the Persian mystic a best seller in America’s seeker culture.” Beginning in the 1920s, it came to be more commonly understood that the essence of religion was to be found in the solitary individual, who, alienated by the processes of modernity, was free to appropriate from religious traditions “as spiritual resources.” The concept of solitude as a path to spiritual realization continued into the end of the century and self-help began to sell. Half of the top nonfiction books in 1994 related to spiritual themes. “Religious seeking becomes comparable to test-driving various automobiles to see which delivers the most satisfaction on Whitman’s open road.”

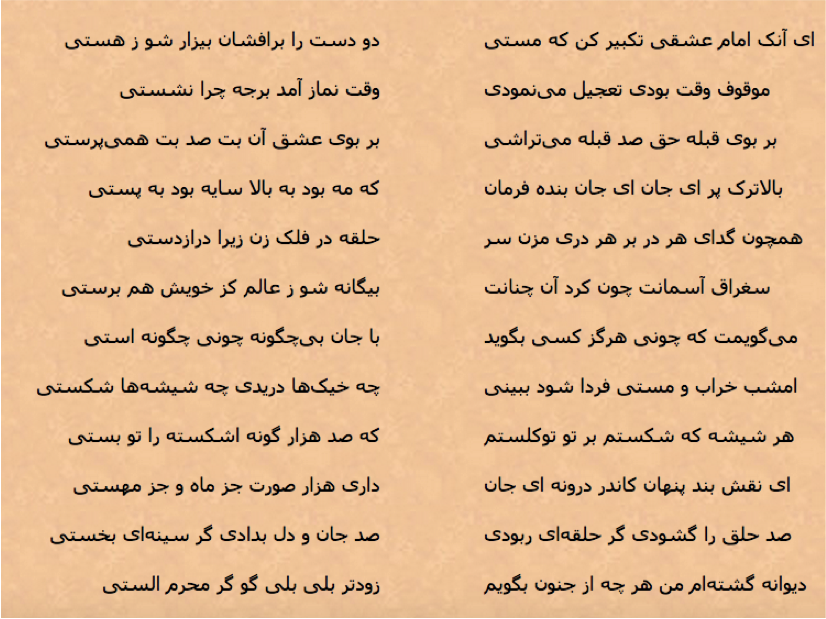

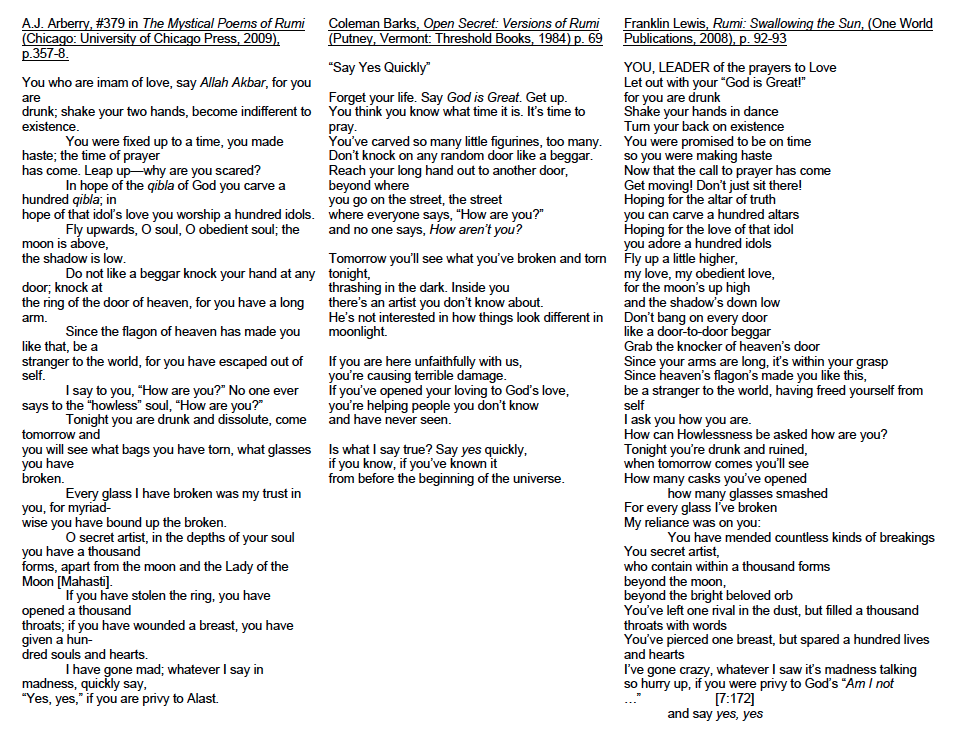

Barks’s translations offer a quick spiritual fix to America’s “spiritual hunger” because they strip Rumi’s work of its complications. This is not without consequences. Abu al-Fazl Horri, who wrote a critical assessment of Barks’s translations in 2010, suggests that we call Barks’s publications “mutations” rather than versions: “In fact, from the point of view of translation studies, Barks, by methods of ‘strangeness-removal,’ Barks transforms Mowlana, meaning ‘Rumi,’ into otherness and a dislocated non-eastness.” Taking a tip from Horri, I will show four poems below. This poem was selected because it has been translated by three very different translators who each show a different set of priorities and methods in their translation process. The first, the original text from Rumi; the second a translation of the same poem by A. J. Arberry; the third a secondary translation by Barks based on Arberry’s translation; and fourth a more recent translation of the same poem by Franklin Lewis, one of today’s top Rumi scholars and translators.

Each of these is a different poem entirely. Arberry, perhaps the most prominent translator of classical Persian poetry into English, is generally regarded as accurate but too literal. This is apparent in lines like “quickly say, / “Yes, yes,” if you are privy to Alast.” or “In hope of the qibla of God you carve a hundred qibla; in / hope of that idol’s love you worship a hundred idols.” Arberry’s translations of classical Persian poetry remain an important contribution to scholarship today because of his extensive knowledge of Persian and vast body of translations. Arberry was a part of the colonial era of Orientalist scholars who often fell into tropes that excessively otherized the peoples of the Middle East. In this sense, Arberry’s work also represents an important part of the history of English translation from Persian, which more recent scholars have built from and improved through various negotiations and debates over the last century.

In Barks’s version, several images are collapsed or simplified, at the expense of the poem’s tone and references to Islamic teachings. The poem, for one, is much shorter in length than Rumi’s. This is because many lines are compressed. For example, the first stanza of 8 lines is meant to represent 14 misras from the original text. Also, a reference to God, “بیچگونه” or “howlessness” is erased and confined to the human realm of “the street / where everyone says, “How are you?” / and no one says, How aren’t you?” thereby taking God out of the equation. This is representative of a trend in Rumi translations, “in which Rumi is depicted as a mystic who is only slightly Islamic.” The tone of Bark’s poem is one of a nonchalant individual, asking superficially paradoxical questions and making nonsensical requests of the poem’s “you.” When disconnected, the disparate images seem reckless, but in the original they are part of a highly structured rhythm and rhyme and set of classical images cleverly organized like only Rumi could.

Franklin Lewis has also been criticized for making his translations too academic. In Swallowing the Sun, however, Lewis sought to make accessible translations. In this sense, Barks and Lewis had similar intentions in mind. But unlike Barks, Lewis does not essentialize Rumi’s message. Lewis’s translation is in an accessible, image-heavy language, and several liberties are taken with the format including the shortening of lines and the transformation of the poem into a free-verse style, which mimics the quick motion in the original poem. Lewis also makes a footnote to a verse from the Quran, thereby making the connection to religion explicit, perhaps even more so than in the original text (although it could be assumed that Rumi’s contemporary readers would make this connection on a first read).

“Ibrahim Gamard, Rawan Farhadi, William Chittick, and Franklin Lewis disapprove of making versions. I understand the objections. What I do is a homemade, amateurish, loose, many-stranded thing, without much attention to historical context, nor much literal faithfulness to the original.”

—Coleman Barks, Rumi: Soul Fury

This is not a debate about good translations and bad translations. Nor is it about veracity versus unfaithfulness to the text. My friend’s mom back in Idaho, I should add, told me with a smile that there is something about Barks that she likes, that she doesn’t see other translations as getting quite the same. This essay is just to say that as a native English speaker, I wish I had easier access to translations of Rumi that did not oversimplify or seek to please romantic expectations. I would also like to trust that an accessible translation of Rumi would come from a translator with proficiency in Persian. Unfortunately the standards for Persian translations does not include this proficiency.

Barks, like other poets who seek to make secondary translations of poetry in many languages so that a mainstream American audience can understand, rather than finding a universal poetic essence, collapse distinct poetries into a familiar, feel-good, spiritual quick-fix. The strength in poetic expression is twofold: to show the human in all of us, but also to show us a new way of thinking about something, sometimes drastically so. Through Barks’ secondary translations, the lay reader sees the former but is deprived of the challenges of the latter.

Re-rendering orientalist or literal translations perpetuates the mistakes of past translations rather than move past them. We should not disregard past work on Rumi. Rather, we should analyze it, compare it with the original text, and suggest new translations that can benefit from the last half century of self-reflective translation studies and literary theory.

Bibliography:

Coleman Barks, The Essential Rumi (2004: Harper Collins)

Coleman Barks, Rumi: Bridge to the Soul (2007: Harper Collins)

Franklin Lewis, Rumi: Swallowing the Sun, (One World Publications, 2008)

Schmidt, Leigh Eric, Restless Souls: The Making of American Spirituality from Emerson to Oprah (New York: Harper Collins Publishers, 2005)

“کلمن بارکس» کیست؟»” Fars News Agency. http://www.farsnews.com/newstext.php?nn=8502270287

“Corrections of Popular Versions of Poems from Rumi’s Divan,” Dar al-Masnavi, http://www.dar-al-masnavi.org/corrections_popular.html

حری, ابوالفضل, «غرابتزدگی معضل ترجمهّ رومی آمریکایی بارکس», مطالعات ترجمه, سال هشتم, شمارهّ سی و دوم, زمستان ۱۳۸۹

Wuthrow, Robert, After Heaven: Spirituality in America since the 1950s (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998)

11 comments

Very well written land although I admit to only knowing Rumi from an American point of view, I can see the struggle to accurately reflect the genuine intent without having it fall on deaf ears. Good job in analyzing the various sides!

Thanks to Kat Thornton for this timely contribution. She is right to point to the mode of literary appropriation, which is not limited to English or Barks, as a problematic approach to translation. But perhaps this critique can be articulated without falling into other orientalist traps such as the “Golden Age” of Persian poetry, which has also been co opted by nativist Persian literary historiographers. The “Golden Age” paradigm suggests an uncritical judgement value, and in this case exalts the Khurasani and Eraqi “styles” of Persian poetry while deeming all that came after them (i.e the so called “Indian style”) as degenerate and unworthy. This construct is the product of the very exoticizing and romanticizing approach of Orientalist historiography admirably critiqued in this essay. These traps are plenty, and the only way to expose and avoid them is through dialogue. Again, thanks to the author for raising important points for further discussion.

Mostly agree, but it’s hard to fault Barks when most other translations generally fall flat.

I personally like translations by Kabir Helminski; as a self-professed Mevlevi I trust him to be loyal to Rumi’s Way

I personally enjoy Jawid Mojadeddi’s translations. Not only is he a native Persian speaker and so maintains the rhyming couplets of the Masnavi, he is also a scholar of Islamic studies and Sufism so he maintains the themes Rumi talks about in his poetry, and then also adds relevant notes to accompany the work in case someone does have much of a background to Islamic terms and ideas.

Thank you for the reference to Prof. Jawid Mojadeddi!

Greetings from Boise – it took a couple of years for this blog to reach us (slow internet out here…). I am the ‘Cowboy’ you mention whose life has been changed by Rumi’s poetry. Connecting people with Mevlana Jelaluddin Rumi is joyful work. 60-100 people show up for these gatherings. Thank you for sharing word that you heard about us!

I suspect you will be happy to know we value Mr. Barks’ contributions without over-revering them. We are well aware of the limitations of Coleman Barks’ work and regularly show the paths beyond his work, which await any and all curious seekers.

Our caravan gathers four times a year to share Mevlana’s poetry. About ¼ of the audience is Persian, so we enjoy Rumi in English and Farsi, with multiple Persian voices each time. The Persian folks generally share their own translations, from their hearts. These are among the coolest! We conclude with tea, conversation and Persian desserts, all for free, thanks to our wonderful library and sponsors.

I’m trying to find an out of copyright English translation of Rumi’s A Moment of Happiness so wondered if anyone can help me source one?