The below is an article written by two of our editors-in-chief, Beeta Baghoolizadeh and Rustin Zarkar, about our newest project that will be launched next week: the Ajam Digital Archive. If you are interested in contributing your own family items to the Ajam Digital Archive, email us high-quality scans of documents and photographs at archive@ajammc.com and submit information about your contribution here.

For the past three years, Ajam has supported exciting research on the lands stretching from Anatolia to Central and Southern Asia by publishing articles, photo essays, mixtapes, and podcasts that shed light on the region’s diverse realities, histories, and cultures.

In order to expand our range of approaches, we have recently introduced the Ajam Digital Archive. The archive is dedicated to documenting lived experience from across the region, and is a space that we can all engage with—be it by contributing family documents, photographs, and media, or by perusing it and using it towards personal research projects.

A user-generated and crowd-sourced digital space, the Ajam Digital Archive will promote research by enabling individuals to take part in preserving pieces of 20th century life across the regions we have come to refer to as Ajamistan due to the kinds of historical, cultural, and intellectual connections that have long defined them (for more information on the meaning of the word “Ajam” and the reason we use it to describe these lands, please read “Why Ajam?”).

We want to invite you to join the knowledge-sharing process. By creating a space where you can contribute documents, photographs, and other media from 20th century life, the Ajam Digital Archive represents a collective effort in preserving the memory of daily life as it was lived.

A People-Driven Archive

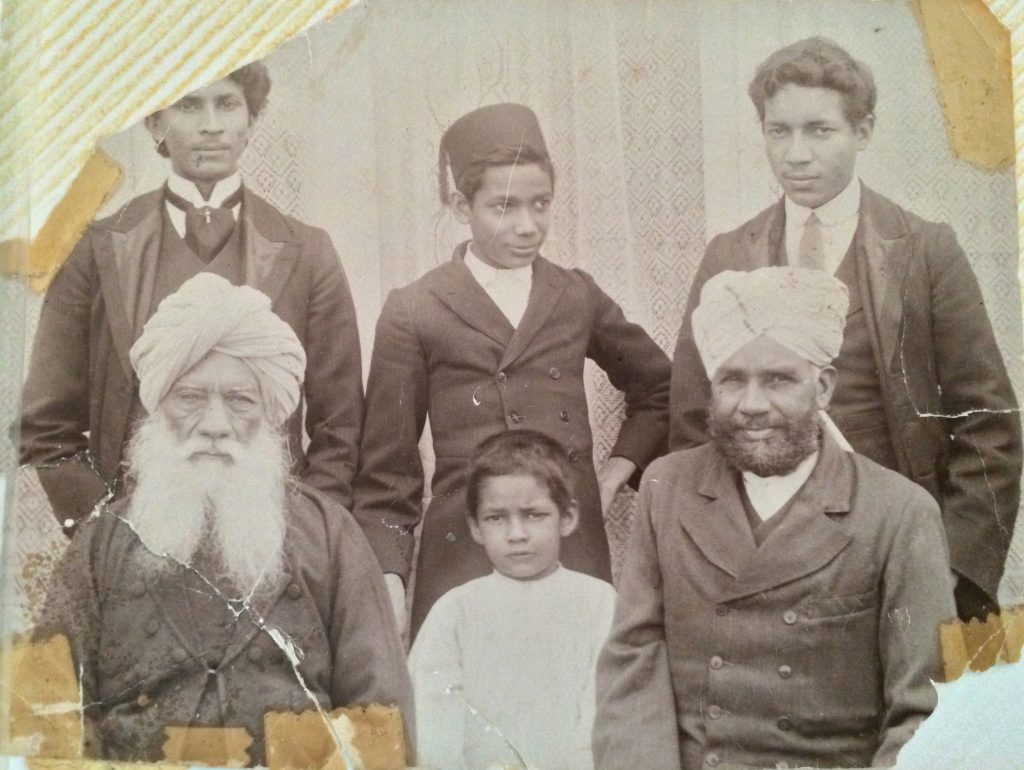

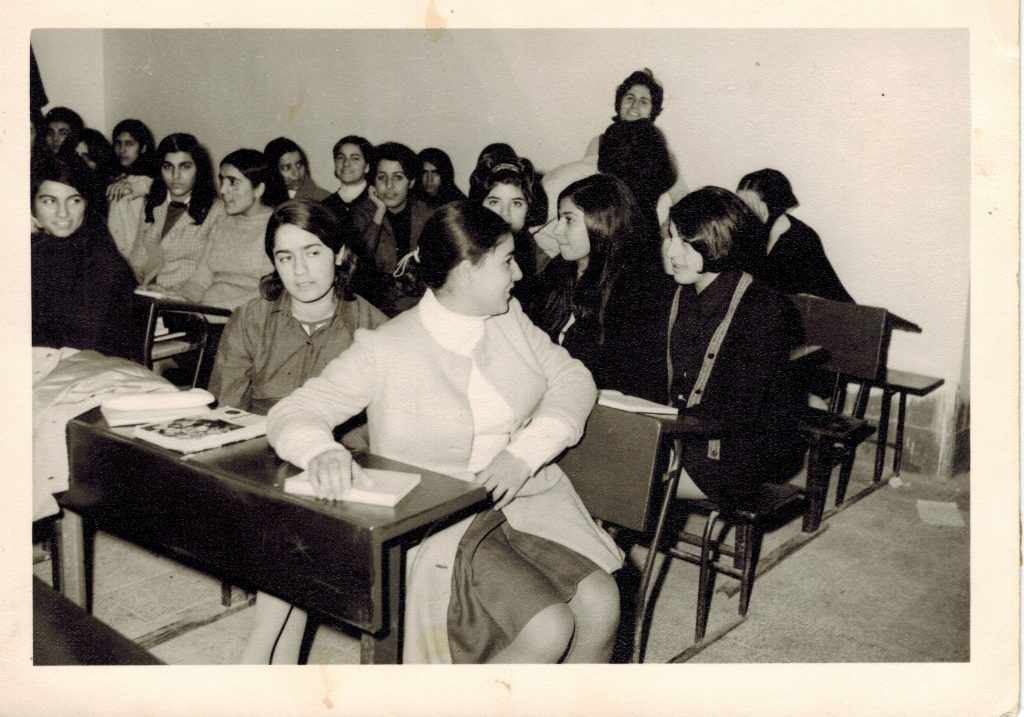

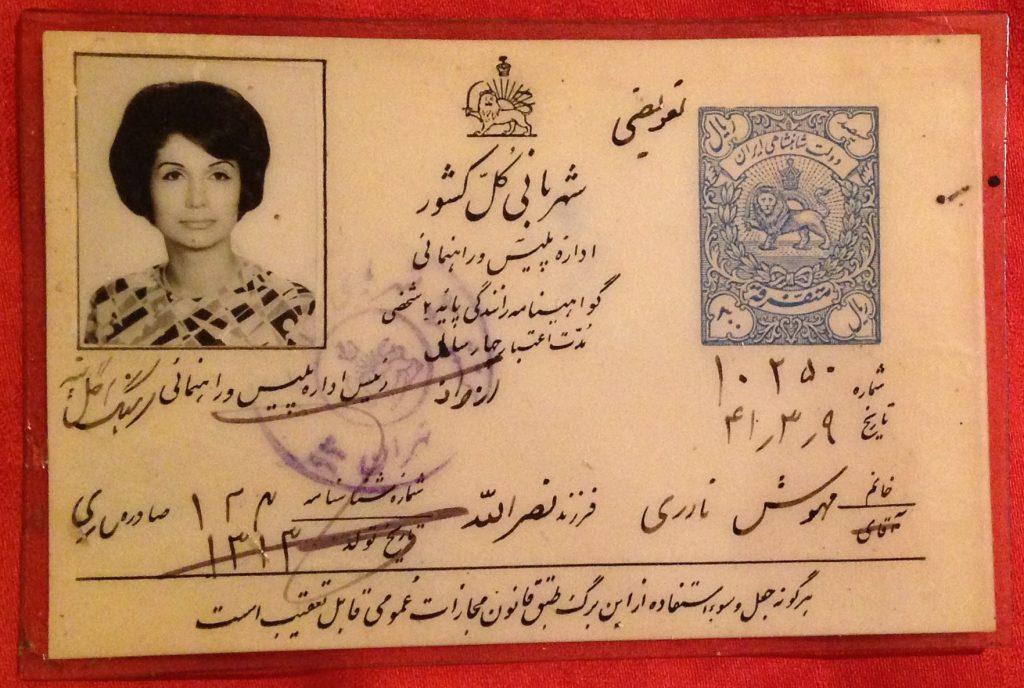

We are archiving everyday objects because family histories are important. Too often, history has been written from above, and the past has been understood through the lenses of grand ideologies. But understanding the past through family history allows us to see a different kind of world, a world that is far more complex than those grand ideologies would have us believe.

Family histories tell us how people actually lived and how they experienced the world around them. How people conducted their daily lives, their social, cultural, and political routines, and how those big historical moments and changes affected real people’s lives in small and big ways. The items collected for the Ajam Digital Archive will allow us to document and record history from below—how it was actually lived, experienced, and understood. It is precisely these histories that were ignored in favor of tales that focused exclusively on wars and revolutions, rarely giving us a sense of how life was lived amidst it all.

By serving as an accessible space for objects not traditionally included in historical narratives, the Ajam Digital Archive will allow us all to participate in history-making, weaving together personal and familial stories and doing the work of historians.

But then, why history? The problem is that history cannot be contained in the 200 pages of a book. Many see History as the inevitable march of time, a sequence of causes and effects that ultimately determine where we are today. Textbooks deliberately present history as one long cohesive and coherent story with a seemingly finite number of events. Even though the authors intend to illuminate the past, history-writing is always shaped by the attitudes and circumstances of the present.

In order to build these narratives, historians rely on materials from earlier times, which have often been collected in specific sites. During the late-18th and 19th centuries, governments began forming archives and the idea of history as a story written by elites for mass consumption became increasingly dominant in the public imagination. The structural changes cemented the idea that “sources” stored by state-run institutions should be consulted for the writing of history. These developments had profound consequences regarding the types of documents stored in the archives, as well as who can access them. They also highlight how deeply important archives became for the way history is written and the way societies came to understand themselves.

Re-Imagining the Archive

In the case of most “public” archives, the state presides over all elements of the archiving practice. National governments determine the value of different documents, preferring to preserve official and bureaucratic texts such as land deeds, tax documents, and diplomatic notes. In modern, patriarchal societies, these documents reflected the worlds of wealthy men, excluding much of the society’s population from the pages of history sources, and therefore, books. Other documents, including early anthropological studies, geographic surveys, and ancient manuscripts, were created or procured through imperial projects that involved pillaging the important texts of colonized or subject peoples around the world.

Thus, archives are sites of power where the class, gender, and colonial relations are intertwined with knowledge production. Additionally, the state acts as a gatekeeper to the archive, limiting access to particular individuals or groups based on the changing political environment. In most cases, state archives require referrals and recommendations from universities and other institutions, thus keeping these materials away from non-professional historians, ultimately restricting who can attempt to imagine and explain the past for a wider audience.

Our awareness of these circumstances prompted us in creating a archive that challenges this imbalance in power dynamics: a people’s archive that aims to preserve more personal histories, and in which content is both generated by and accessible to everyone. Instead of reaffirming a monolithic History, we are making room for histories.

Reframing Historical Narratives

Currently, the Ajam Digital Archive is collecting media from a broad geographic region, rather than limiting ourselves to national boundaries, so users can note the shared cultures across Ajam’s geography. We have also involved members of our communities in our project, and have already partnered with Iranian Alliances Across Borders (IAAB) to create a grassroots effort in populating the archive. Over the next few months, we look forward to having more fantastic organizations from other parts of Ajamistan join the project.

Thanks to our contributors, the Ajam Digital Archive will launch with a variety of different media, including wedding portraits, religious recordings, personal mementos, family trees, military paraphernalia, and so many other media that we are excited to share with you soon. But you should do more than view these items–if you agree with our vision, we are asking you to participate and contribute what you can.

We want the Ajam Digital Archive to be a democratic space–one that goes beyond those who consider themselves experts and draws upon the experiences and interests of our larger audience. We’re asking you to step up and not be an audience any longer–join the Ajam Digital Archive as a contributor and share what you can to change how we write our histories.