The following article was written by Kyle Olson, a Lecturer in Archaeology at the Department of Anthropology, Washington University in St. Louis. He writes about the relationships between archeology, cultural heritage, and development in the Middle East. Follow him on Twitter: @olsonkyleg

***

After decades of international isolation, Iran’s desirability as a tourist destination rose in the 2010s. International guidebooks rated the country highly, Western travel television hosts such as Anthony Bourdain and Rick Steves produced episodes in Iran, and a new generation of sightseers and backpackers flocked to the country. International hotel chains returned after a forty-year hiatus during which Iran’s geopolitical pariah status stemmed the flow of visitors. This growth in tourism during the past ten years was no accident. It was the result of government development policy under the Rouhani administration designed to stimulate domestic, regional, and global demand to visit Iran’s famous historical, cultural, and religious monuments.

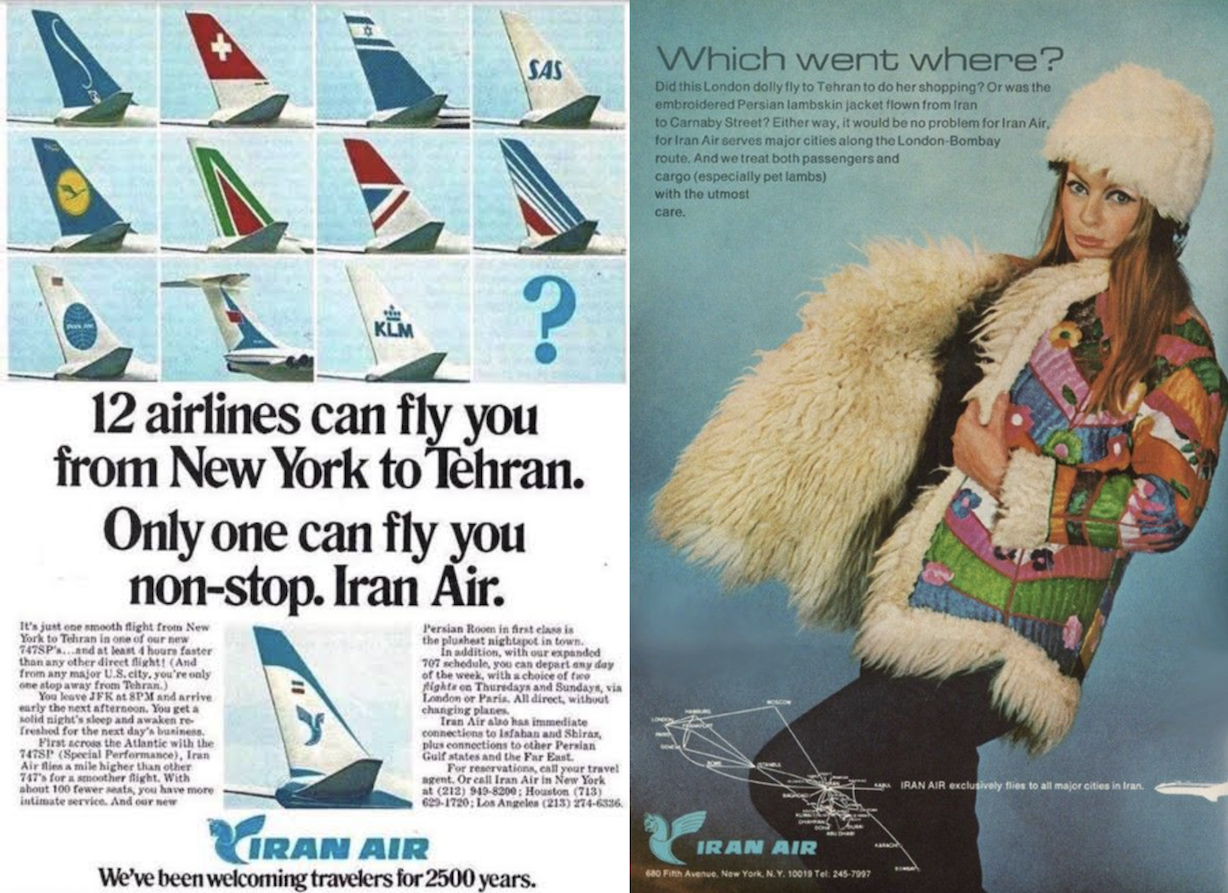

The boom years of 2015-2019—the interval between the signing of the Nuclear Deal and the onset of the Coronavirus pandemic—saw record arrivals of tourists from Europe, East Asia, and elsewhere in the Middle East. Increased numbers of Americans visited Iran as well, at least until reciprocation of Donald Trump’s “Muslim Ban” effectively ended their ability to obtain visas. These years call to mind an earlier period in the history of tourism in Iran. During the 1960s and 70s, Iran was among the most popular Middle Eastern destinations for globetrotting tourists, owing to its reputation as a land of history, culture, hospitality, and unique travel experiences.

Recent research published in in the Journal of Heritage Tourism by Christina Luke and Madison Leeson on 1960s-70s agreements between Iran, UNESCO, and the United Nations Development Program shows how the country acquired this cachet as the result of deliberate efforts by policymakers.

Iranian and international planners promoted tourism as a means of stimulating development via conservation, construction, and bringing foreign currency into the country through the hospitality and service sectors. The tourism itineraries designed by Iranian and international planners in the 1960s and 70s swiftly became standardized and have remained largely intact to this day, despite the massive changes to Iran’s society and place in the world in the decades since.

The impact of these plans can be seen in a collection of promotional materials from this earlier period of thriving international tourism that was recently acquired by the AjamMC Digital Archive. The collection includes a postcard, two travel brochures, and a hotelier’s guide to Esfahan dating to Spring 1971, reflecting the planning visions, aid agreements, and optimism of the time. These documents are not only a window into the past of economic policy but also illustrate how heritage became so important to Iran’s tourism industry today.

The items in the AjamMC Digital Archive belonged to Theresa Howard Carter, a trailblazing archaeologist of Southwest Asia and North Africa and professor at Johns Hopkins University active in the field from the 1950s until the 1980s. They relate to Carter’s trip to Iran in April-May 1971, a three-week archaeological group tour sponsored by the Penn Museum. Her ostensible objective—in addition to sight-seeing—was to assess the situation on the coast of the Persian Gulf between Bushehr and Abadan and to make connections to support a permit for survey and excavation to be conducted in Winter 1971-72. Ultimately, Carter’s April 1971 permit application for fieldwork was denied by the Iranian government and she never conducted archaeological fieldwork in Iran.

Her initial tour went as planned, however, with the itinerary almost exactly matching the central corridor designed by Iranian and international tourism planners of the time. As a consumer of a chartered tour, Carter stayed in the finest hotels and visited the most heavily invested-in heritage sites. It should perhaps be no surprise that an archaeologist would be drawn to the areas of Iran that feature its most spectacular historical monuments. But, the charismatic sites that she visited were key in the multilateral international cooperative plans that structured the development of the tourism industry in Iran—and which continue to be central to its tourism infrastructure today.

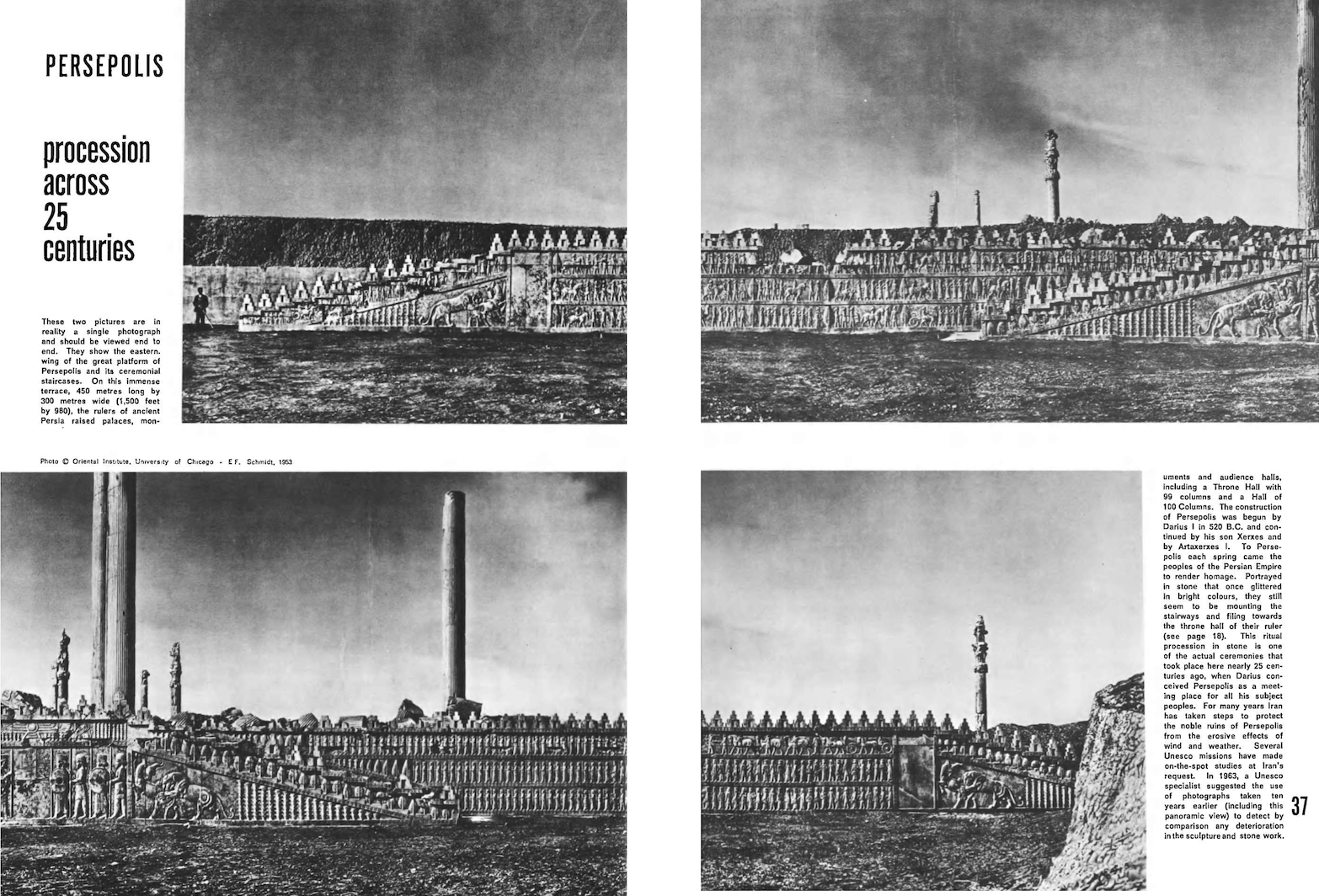

The first item in the collection is the reverse of a postcard dated May 3rd, addressed to her husband, Edward C. Carter, and sent by airmail from Shiraz. She describes Shiraz as magnificent, filled with roses, fountains, and pools. She characterizes local destinations such as Pahlavi University (now Shiraz University) as “most impressive” and Persepolis as “unbelievable.” She provides details about the itinerary and travel as well, noting that despite being only 45 minutes by air, Bushehr was at the time inaccessible. Carter remarks that the travel schedule of the tour is grueling, extending from 7am to midnight. The obverse of the postcard is not shown, but it is captioned “A Painting Tableau in Golestan Palace Teheran, Iran Museum,” and credited to Malek Araghi, which allowed for it to be identified.

A few other telling historical details can be gleaned from the reverse, including from the postage stamp, which features the ruins of Persepolis, a portrait of Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi, royal insignia, and the stamp duty (8 rials, or approx. $0.10). The card is marked as “Printed in Italy” but published by Tabanfar, Naser-Khosrow Street, Tehran. Naser Khosrow Street—located north of the bazaar district—is one of the oldest in Tehran and a tourist destination in its own right, as it features many historical and architectural landmarks including Golestan Palace, the court of the Qajar Dynasty, and Dār ul-Funun, Iran’s first modern university (est. 1851).

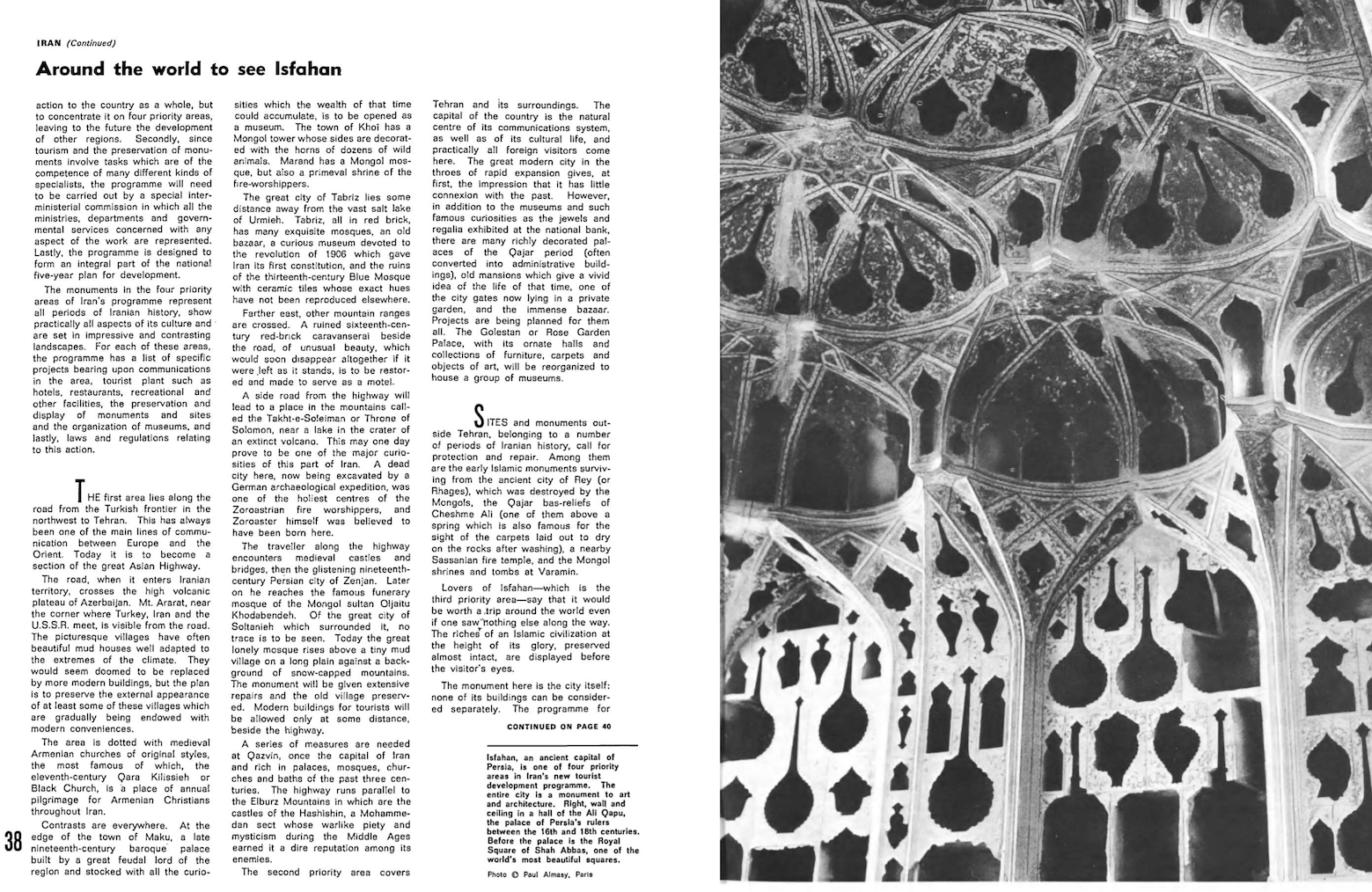

Carter’s archive includes two pages from a large-format tourist’s guide to Esfahan. The guide advertises the Shah Abbas Hotel, converted from the Safavid-period Madar Shah caravanserai. The guide presents a wealth of information, including the hours of operation for historical monuments (separating them into “mosques” and “other monuments”), as well as listings for shopping centers, hotels (27 in total, including one “deluxe,” two 3-star and eight 2-star), restaurants, a description of local food and drink, extensive listings for travel agencies, overland and inter-city transport, as well as local transit options, and information about newspapers, magazines, the post, and wire services. A fairly standard document, it reveals an orientation toward the tastes of well-heeled, cultured, and monied travelers.

This brochure can be compared to a contemporaneous example in the possession of the author, published by an official government agency, the General Department of Publications and Broadcasting, titled “Ancient Persia, Modern Iran” (see below). This guide presents Iran as a “Cradle of Art and Culture,” extolling Iran’s illustrious past and promising future—with references to the Achaemenids, Sasanians, and Safavid dynasty and present-day Iran’s economic potential represented by its “dynamic growth,” led by its oil industry and ambitious billion-dollar development program.

This framing of Iran’s cultural heritage fit well with the government’s public relations campaigns to play up not only Iran as a glorious ancient civilization, but the Pahlavi regime as its caretaker in the present. Similar to the brochure in Carter’s collection, this document’s reverse provides details concerning must-see destinations (more than half of which are archaeological sites and historic monuments), travel tips and cultural notes, as well as a detailed road-map, which provides suggested tour itineraries of varying lengths.

The Carter collection contains two additional travel brochure covers. They appear to be produced by the same agency, as the fonts, visual repertoires, and color palettes are stylistically consistent. One of the covers features the provinces of Hamadan and Kermanshah, located in the western Iranian highlands, between Esfahan and Tabriz along the planned tourism corridor. The upper register of the cover depicts mountains, hills, and stylized vegetation. The lower register presents a highly abstracted image of the heritage site Taq-e Bostan, as well as traditional handicrafts.

The other brochure cover comes from a guide to Khuzestan province, featuring a greater variety of motifs. These include an archaic stepped arch structure, several large sunbursts, palm trees, columns, a stylized vaulted gateway, as well an oil derrick and a hybrid archaeological-modern motif combining a classic Susa I pottery design (ibex) with a gridded globe (which should be noted, was a frequently used logo of the Iran National Tourist Organization at the time). The juxtaposition of ancient (e.g., prehistoric pottery), traditional (e.g., handicrafts) and modern (e.g., hydrocarbon infrastructure) emblems is particularly telling in terms of how these destinations were marketed to travelers.

The symbolism, textual rhetoric, and pre-designated routes that these guides proffer indicate what kind of tourist Iran’s government hoped to attract. This ideal tourist —wealthy and cultured—stood in contrast to Iran’s notoriety as a stop along the “Hippie Trail,” which drew young visitors with a penchant for psychoactive substances and who were less interested in urban Iran’s elite watering holes.

By contrast, the planners of Iran’s developing tourism industry in the 1960s and 70s wanted to draw moneyed tourists to both the historical centers of Iranian civilization and the loci of its modernization who could, upon returning home, further burnish Iran’s reputation as a growing and respected power on the world stage.

The documents reflect Iranian planners’ keen awareness of the difficulties other countries faced in pursuing tourism-driven development schemes during this period. As often as not, so-called “fun-in-the-sun” projects, while successful in bringing in visitors and money, only enriched the multinational corporations who had financed the construction of resorts at the expense of local populations. In seeking to avoid a similar fate, Iranian policymakers instead sought planning assistance from international partners such as the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) and United States Agency for International Development (USAID), rather than from private developers.

Luke and Leeson’s recent article shows that beginning in the early 1960s, these aid and technical assistance organizations advised the Iranian government on the conservation of archaeological sites, the construction of museums and hotels, and the expansion of road networks. In its promotional materials, UNESCO described cultural monuments—understood as tourist attractions—as fundamentally no different from other categories of national assets and resources. UNESCO’s explicitly stated rationale was that tourists from North America and Western Europe could travel just about anywhere for a seaside vacation, but that travelers would journey to countries like Iran, Jordan, Ethopia, India, and Nepal to experience unique cultural and historical monuments.

According to this view, countries like Iran needed special technical assistance and aid programs to develop these sites as tourist attractions, to encourage year-round flows of visitors not dependent upon summer weather, and to facilitate ease-of-access to far-flung sights and destinations. Luke and Leeson show how international planners believed Iran needed a special program for two reasons. First, due to the huge size and relatively underdeveloped nature of the country, and second, due to a strong will from state planners to preserve and display monuments. Both international and Iranian planners recognized the huge scale of investments that would be required, for everything from site conservation and protection, to administrative and technical “machinery,” the training of cadres of specialists, and the construction of museums. Moreover, UNESCO stressed the urgency of the need for a developmental program to take advantage of the already-growing number of tourists already traveling to Iran, encouraged by the expansion of air travel and modern communications.

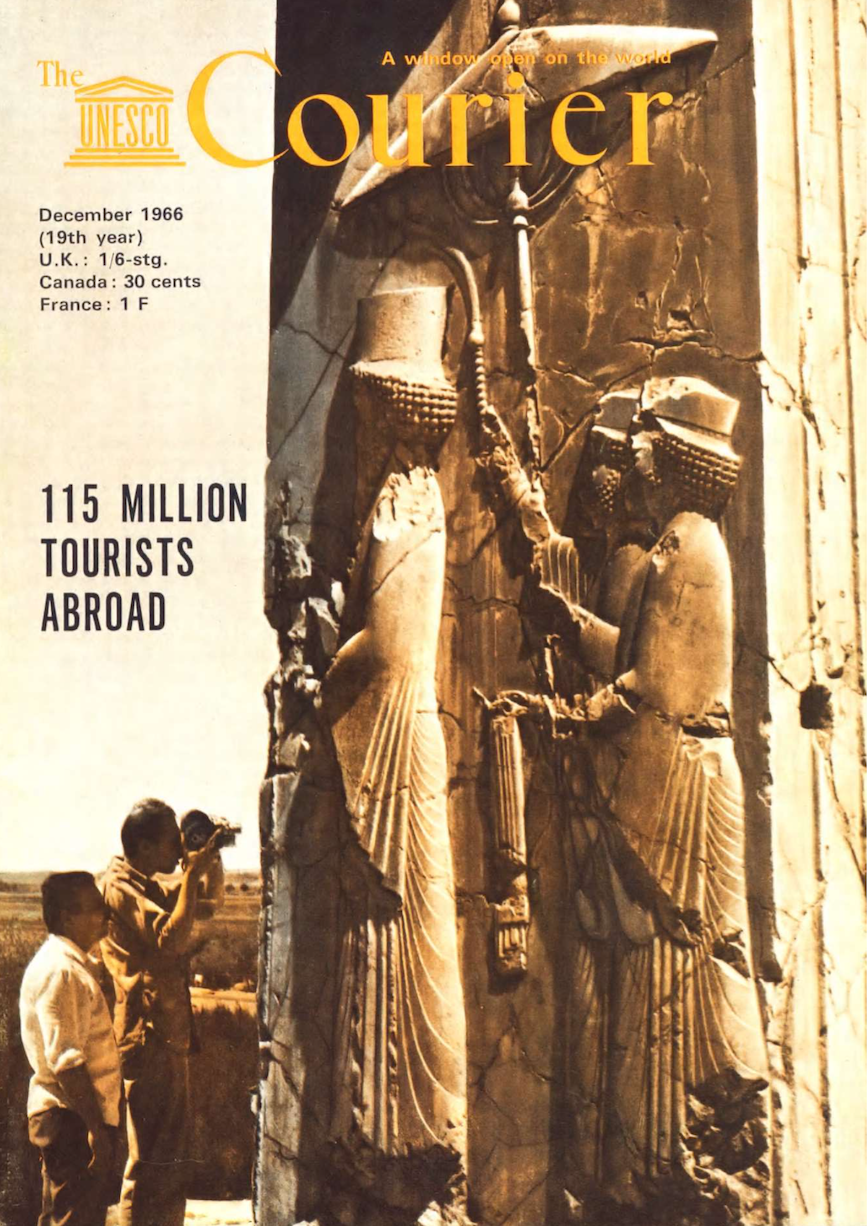

In 1966, UNESCO outlined the parameters of their Iran plan in their monthly periodical The Courier, emphasizing three of its key features: (1) concentration of investment on four priority areas rather than the entire nation, (2) formation of an inter-ministry cooperative commission, and (3) making tourism a key part of the national five-year development plan. The four priority areas were selected based on particular criteria; these included the desire to present the full length of Iranian history and show the diversity of Iranian culture, set in distinct landscapes.

For each area — Qazvin-Tehran, Tabriz, Esfahan, and Shiraz — specific domains were to be targeted for investment: preservation and display of sites and monuments, museums, hotels, restaurants, recreational and other facilities, as well as laws and regulations to manage this newly expanding sector. In 1968, the Iranian government signed a landmark agreement with UNESCO and UNDP for an aid package of $4 million USD—ca. $35 million, adjusted for inflation—to elevate the profile of cultural tourism and integrate heritage planning into the country’s national development plan. Crucially, what Luke and Leeson show is that the primary aim of this agreement was to create the infrastructure needed for the “tourism corridor” that Carter followed, stretching from Shiraz through Esfahan to Tabriz, before arriving in Qazvin and Tehran.

While scholarship on the development of tourism in Iran has tended to focus on infrastructure, investment, and planning, Theresa Howard Carter’s collection is significant for understanding how tourism was marketed to potential travelers. Carter’s materials demonstrate the results of efforts on the part of policymakers to improve communications, hotels, restaurants, recreational facilities, and the preservation and display of sites and monuments. Furthermore, these documents show the effectiveness with which the planners implemented their vision of the “tourism corridor” to structure visitors’ itineraries.

In the end, the documents in this collection might seem to be mere mementos of a long gone era. But as international tourism to Iran was resurrected in the 2010s, the primary tour circuits in the country continued to follow those laid out in the 1960s-70s, revealing the lasting impact and relevance of the planning behind them.

While today, the numerical majority of tourists who visit Iran are religious pilgrims from the surrounding region, for those tourists from North America, Europe, and East Asia, the routes that they will likely follow while visiting Iran have changed little in the past five decades.

While the Carter collection is small, its contents speak to a much larger set of issues of broad interest to those invested in cultural heritage, tourism, development, and international relations from the mid-twentieth century until the present.