For decades, Turkey has been a transit country for refugees from every geographical direction. While the sheer number of refugees has hit an unprecedented level as a result of the Syrian refugee crisis, there has also been a significant shift in the kind and quality of life for most refugees. For refugees in Turkey, indefinite stays have become the norm rather than the exception, as people are forced to navigate spaces of existence that challenge typical conceptions of borders and refugee aspirations. In understanding the situation of these refugee communities, we are brought face to face with contradictions and paradoxes that define daily life for thousands of people.

While much attention has been brought to the plight of Syrian and other refugee groups in Turkey, Afghans are often forgotten as their forced migration from Afghanistan appears to be old news after decades of conflict. This is despite the fact that there are over 30,000 Afghan refugees currently residing in Turkey. The situation of this community in Turkey will be explored based on my own ongoing research and involvement with the topic. Since 2012, I have been attempting to document the experiences of Afghan refugees through periods of ethnographic fieldwork and working as a representative for the Coordination Group of Afghan Refugees, a grassroots human rights organization made up of Afghans hoping to alert the world to their struggles.

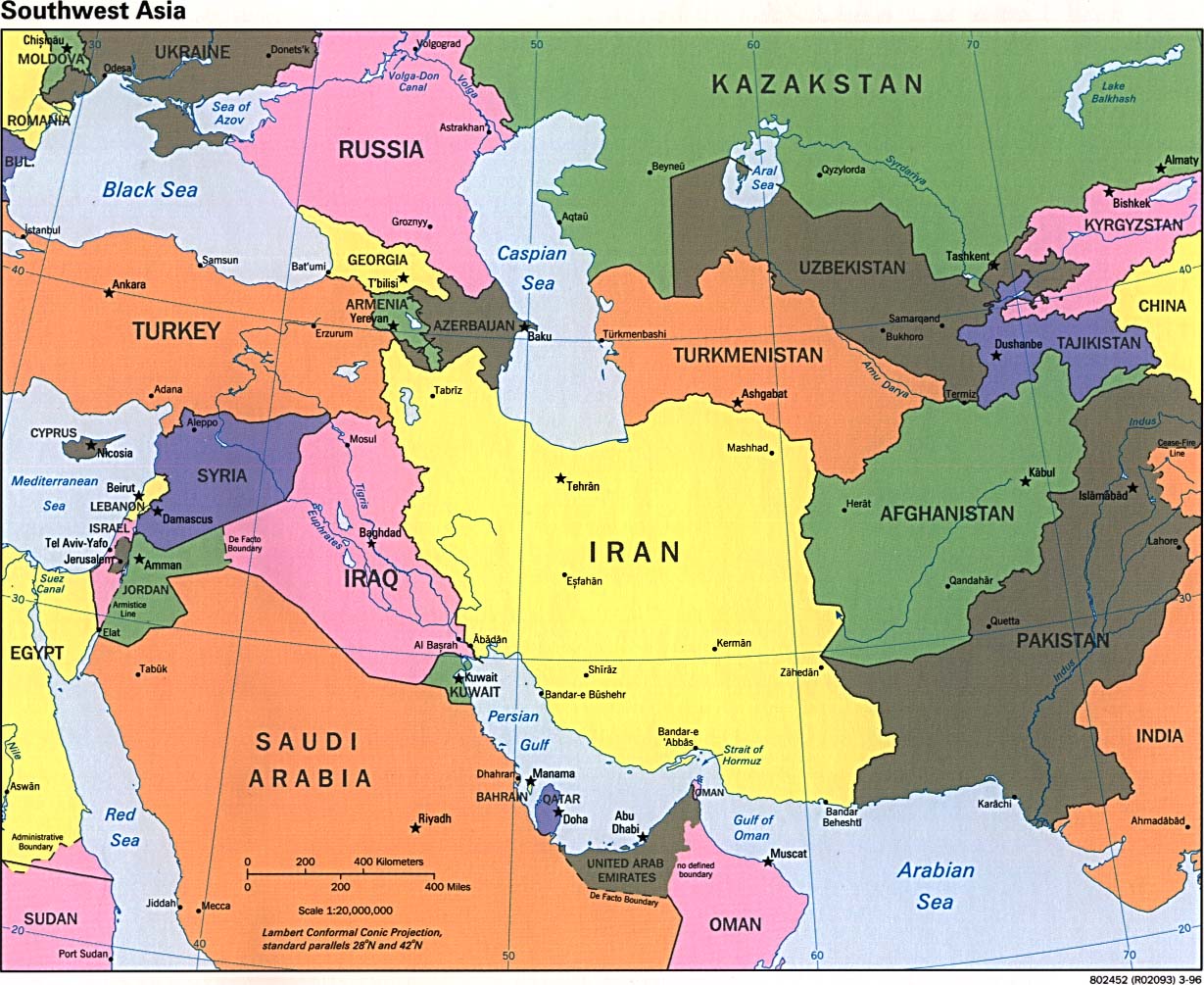

For many outsiders, the very presence of Afghan refugees living in Turkey is a surprise in and of itself because of the distance between the two states. But in recent history, the relationship for migrants and refugees between the two countries is far from new. During the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, Turkey offered resettlement to a small number of Turkmen and Uzbek refugees from Afghanistan as a show of “Turkic solidarity.” At the time, most people fleeing Afghanistan as refugees were seeking safety in neighboring countries like Iran and Pakistan.

But since the US invasion of Afghanistan, human rights issues for Afghans have deteriorated in Afghanistan, Iran, and Pakistan. In turn, Afghans began to newly move to Turkey albeit in much greater numbers. As of 2015, there are over 32,000 Afghans currently living in Turkey who are seeking asylum. This is but a small slice of the 2.5 million Afghan refugees who live across the globe. These Afghan refugees, be they from Afghanistan, Iran, or Pakistan, share a precarious situation in Turkey because of the nature of international refugee regimes and Turkish asylum policy.

Despite being home to a huge refugee population, Turkey does not formally accept refugees in the way typically articulated by the refugee convention. This can be attributed to a geographical limitation the government put in place when signing the 1951 Refugee Convention, wherein the state only agreed to accept refugees from Europe. This policy was made during a particularly strong era of Turkish nationalism in which reforms to position the country as “western” rather than “eastern” often dominated policy.

Despite this limitation, Turkey’s geographical location means it is invariably home to many refugees who are not European. To that end, the government works with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) to temporarily give Afghans and other refugees asylum-seeker status. But, these refugees cannot truly apply for asylum in Turkey. They are simply entitled to wait in Turkey until they receive third country resettlement or return to their country of origin. In the meantime, they are in legal limbo in which their status is unclear. They have the right to reside in the country, but lack the right to work or the kind of state assistance needed to avoid working. To be a refugee in Turkey in turn requires navigating life between a state-acknowledged realm of illegality, while also coping with the uncertainty of how global trends can affect the fate of an entire refugee population.

The idea of refugee resettlement from Turkey as it currently exists has developed a major flaw. Despite decades of Afghans fleeing their home countries, few countries take in Afghan refugees. The United States, for example, only settled 661 Afghan refugees last year: this figure includes Afghans who applied for asylum across the globe, which could include other countries such as Pakistan, Iran, and India. This trend continues despite awareness that the hardships many of these asylum-seekers face often qualifies them for refugee status. Whereas certain refugee groups are offered resettlement in European countries or the Americas in larger numbers, Afghan refugees are so overlooked in international refugee concerns that some individuals in Turkey have been waiting for permanent citizenship elsewhere since 2006.

What results from this combination of legal uncertainty and failed resettlement promises is a uniquely tortuous and banal way of life for thousands of people. Most visibly, the daily life of an Afghan refugee in Turkey is tied to the struggle to provide for one’s own existence without many basic rights or services. Refugees do not have the right to legal work in Turkey, yet without access to sufficient economic aid, refugees have no choice but to work illegally and in exploitative conditions. Similarly, despite recent reforms in migrant and refugee policies, refugees experience obstacles in terms of educating their children and accessing affordable health care.

But it would be incomplete to try to understand Afghan refugee life in Turkey as just an issue of tangible economic or physical needs. Liisa Malkki’s work on the perception of refugees notes that the refugee is often conceived as an objectified mass that is reduced to its (often physical) suffering. But in the case of Afghan refugees, a major part of the trauma this community faces is something less tangible: the sense of uncertainty that comes with waiting for resettlement, yet also being unable to build a life in the present.

During my fieldwork, I had the chance to speak with Maryam, an Afghan refugee from Afghanistan who was living in Turkey. Her husband was working in Iran when he was deported to Afghanistan, and presumably killed on the Afghan side of the border. Now, as a single mother and struggling head of household, she discusses how uncertainty warps and defines her life in Turkey. This idea of uncertainty, or ‘bela-taklifi’ is a word in Persian that consistently comes up in discussions of how the Afghan community perceives their experiences in Turkey.

Speaking of her life in Turkey, Maryam said: “For two years my children have had their lives wasted in uncertainty (bela-taklif),” she said. “And it’s not clear, are we waiting two years or more? … If there’s no country for Afghans, why did you open the UNHCR’s doors? Why are you giving the Afghans refugee acceptance? You should close the UNHCR doors, and say there is no country, no interview, nothing. Just close the door! Say there are no rights for Afghans. If it’s just for Iranians or someone else, and no Afghans, tell them so they aren’t uncertain (bela-taklif). So they know their own future (taklif).”

To be an asylum-seeker, Maryam demonstrates, is to suffer mentally as well as physically. Even if a refugee is somehow employed, fed, and sheltered, they are robbed of a sense of a future or a stable present. To help outsiders make better sense of the migrant and forced migrant experience, migration scholars such as Jorgin Carling and Hein de Haas have encouraged more emphasis on migrant and refugee aspirations and capabilities. Too often, perspectives on refugees focus too much on the idea of mobility, movement and flight. But in reality, movement and migration are complex processes that are linked to individuals’ aspirations to build a better life in relation to the capabilities they have to fulfill said desires.

In speaking about her dreams, Maryam revealed that her aspirations for herself and her family were just as rich as any person. She wished for the chance for her children to be well-educated, for the means to feed her children, for the ability to buy new clothes for her family, and to be free from the excruciating stress of wondering about the future of her residency or citizenship status. How could one construct any semblance of a “good life” when these aspirations have no chance of being met? Between the possibility of eventual deportation, the unattainable yet-desired idea of resettlement, and the material struggles of poverty, there is no space for fulfilling life-making. Instead, life is marked by meaninglessness, and uncertainty.

I was still a student at the time of my interview with Maryam, and before beginning our discussion, I took the time to explain myself and my research project as part of the consent process. So when it came to better explaining her children’s lives to me, Maryam returned to this discussion to help paint me a picture of their own lives. She said: “Right now, you, you’re a university student. You want your future to be bright, you want to progress, you want to go forward. Our children are just like you.”

This immobile and precarious way of life is in stark contrast to the image of the supposed “waves” of boat migrants flooding Australia and Europe’s shores. The xenophobic imaginary of Global Northern states conjures images of irrational, ahistoric, and unstoppable flows of refugees that show no signs of abating. In response to uproar over these preventable migrant deaths, politicians often reply with the classic statement that there are legal channels for asylum, and that queue-jumpers should not be rewarded.

But what the story of Afghan refugees in Turkey shows is that there is no reward for those who follow the rules or waiting in line for resettlement. Life for migrants stuck between their home country and a destination country is difficult with little hope in sight.

The state of affairs is more than a Turkish issue. Despite the rise of rhetoric to “share the burden” of refugees, refugee crises have instead been externalized and increasingly limited to the regions in which they occur. Although refugee resettlement from camps or transit states is nothing new, resettlement spots have not kept up with the need. At the same time, a direct journey into a safe country for permanent settlement is increasingly difficult. A laundry list of initiatives have been implemented to close-off Europe to asylum-seekers: Frontex, the Dublin Protocols, and the policies of the Schengen Visa zone have pushed refugees further away from potential final destinations. Whereas before the dominant image of refugee exclusion was a space like a detention camp in the United States, the United Kingdom, or Australia, now refugees are stuck in open-air prisons such as Turkey and Libya.

Despite these difficulties, refugees are not just passive victims. Afghans in Turkey have etched out a place for themselves in society. As urban refugees, they largely live and work among local citizens of Turkey, and often speak Turkish or have spent time in Turkish schools. There is a struggling but active Afghan refugee civil society that is developing in Turkey. In spite of this degree of integration, their legal status leaves them underpaid, without access to rights-based justice, and seemingly disposable. The desire of this community for a better, fuller life is clear although the path to such fulfillment remains crowded with obstacles. For now then, the least that outsiders can do is make sure to listen when these Afghan refugees speak, and engage themselves with amplifying their voices.

Those looking to learn more about Afghan refugee issues in Turkey are encouraged to follow @Afgrefugees on Twitter and follow the Afghan Refugee Solidarity Network on Facebook.

1 comment

I am married to a Turkish citizen. We too have no rights to work or access justice or otherwise be treated as a part of the society. It might sound trite but no employer ever bothered with work visas for me either even though I am highly skilled and they needed my expertise and yes they did take advantage – always. This is a problem Turkey can solve and no amount of complaining about Europe and why they don’t take everyone in will change. Turkey can do it, they just don’t want to. So if you live there you will see that we are all subjected to the same “insecurity” for many many years until/if we become citizens. Exactly the same as Afghanis/Syrians living there.