The following article is written by Setrag Manoukian, an Associate Professor of Islamic Studies and Anthropology at McGill University. He is also the author of City of Knowledge in Twentieth Century Iran: Shiraz, History, and Poetry (2012). For more information regarding the book, check out AjamMC’s interview with the author.

Shahrzaad’s Tale is a film about Kobra Amin-Sa‘idi, stage name Shahrzaad, an Iranian dancer and actress well known for her secondary roles as bad girl in some of the 1960s and 1970s blockbuster films, who also wrote blank verses and went on to direct her own film only to fade into oblivion after the 1979 revolution Shahrzaad’s Tale is directed and edited by Shahin Parhami, an Iranian filmmaker based in Montreal who received numerous awards for his previous films.

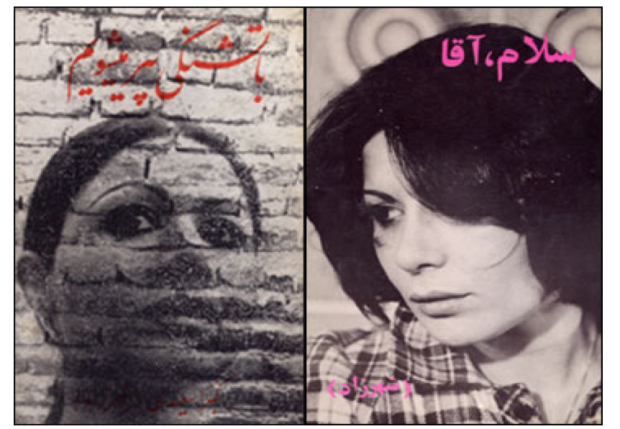

Born in a working-class family, Shahrzaad started dancing in her father’s café in south Tehran before moving to more upscale cabarets. She joined a theater company, and eventually performed in commercially successful films of the so called “film Farsi” genre– in Kimyai’s famed Qaysar (1968), she played a sex worker who hides the protagonist on the run. In those same years Shahrzaad published two books of poetry, and wrote for magazines, moving back and forth between artistic avant-garde and popular entertainment, something that happens quite rarely in Iran and elsewhere. At the end of the seventies, she directed a feature length film and a short movie, one of the first women to do so in Iran. The 1979 revolution turned her world upside down and made the contradictions that had channeled her career even more evident: a life of struggle and abuse, but also of self-assertion as woman and author, became one of solitude and drift.

It took many efforts for Shahrzaad’s Tale filmmaker Shahin Parhami to find Kobra Amin-Sa‘idi and convince her to be again in front of a camera. Besides reconstructing her career, Shahrzaad’s Tale is a film about this quest and encounters. The film opens with Parhami and a younger actress driving to a small town near Kerman, where they eventually meet Shahrzaad in her house. She talks about her difficult childhood, her violent father, and her current poverty, but also reminisces about the highlights of her career with a sense of pride and more than a touch of self-irony.

The film continues in Tehran where Shahrzaad revisits her childhood neighborhood, spends time in the museum of cinema where she sees her photo among those of other famous Iranian actors, and meets some of her old friends and fellow artists. The film culminates in Shahrzaad’s conversations with a group of young middle upper class women, artistically ambitious and colorfully clothed, recruited by the filmmaker to interact with the older, successful, and experienced Shahrzaad. The conversations revolve around acting and film-making but also poetry, the hardship of life, the sacrifice of Iranian martyrs, maternal love and national pride. Shahrzaad acts at times as a mentor, at times as interviewee, at times as a director auditioning her cast, and through these different personas the viewer gets a sense of her courage and sadness– by contrast, the women appear economically at ease but embarrassed by or incapable of coming to terms with the figure of Sharzaad.

Shahrzaad’s Tale is also a film about the history of Iranian cinema and its reception in contemporary Iran. Filled with amazing found footage, the film documents Shahrzaad’s career in images, but also conveys the rhythm of “film Farsi” features with larger than life characters, sexual innuendos and over the top vocal intonations. Composed through interviews, the film shows the place this cinema has retained in contemporary Iran, remembered with nostalgia and appreciation, but also inevitably part of a long-lost era that only lives in its fading negatives –often no more than a few fragments– via individual recollections and the politics of remembrance.

Shahrzaad’s Tale can be certainly described to those who have not seen it as a biopic, a road movie or a film about Iranian cinema of the 1970s. Kobra Amin-Sa‘idi has already gathered academic interest, and one can foresee how she can be made to impersonate narratives about forgotten and suddenly rediscovered movie stars, but also to stand for arguments about the status and role of women, and, in more daring interpretations, to exemplify the history of class, generational and political conflict in Iran. After all, this is what one has come to expect from narratives about Iran, especially outside the country: tales that explain what the country and its people are about, and most and foremost, tales that captivate an audience through stories.

While envisioning these narratives, Shahrzaad’s Tale, as it is befitting its title, detours these tales towards a different use of images, sounds, and words. The elements that make up the film are not assembled together to tell a story: they are composed to show a power I would call poetic: they do so not via morality or judgement, but via the concatenation of images, sound, and words themselves.

A Tale Made of Tales, a Story without a Story

Films tell tales –“what else can a filmmaker do?” says Shahrzaad in the last frame of the film as if reflecting retrospectively on what the viewers just watched, while challenging the filmmaker, questioning his capacity to narrate her tale – but what tale? The tale is many tales, but never quite recomposed as a whole story. The film turns the all too obvious reference to the Thousand and One Nights, embedded in Shahrzaad’s own chosen stage name, into an occasion for showing the impossibility to tell a tale, warranting and deferring expectations even in the title.

To the extent that the film tells a story, this story is not a biography, it is not the tale of a self, a story of an interiority expressing herself: one cannot even say that the film is the story of a life: at the beginning of the film, reconstructing the facts that are supposed to narrate her life, Shahrzaad asks: is this a life I’m living? Man doram zendegi mikonam? With equal force, she repeatedly denies any continuity of time and place to her story, or to any story, refusing to allow herself, the filmmaker, and the viewers to constitute an experience out of her words. There is no experience to rely on, nothing that can help to think the past and the future: as Shahrzaad declares in a key scene, when she leaves a place, she burns everything behind her, and despises nostalgia and wishes.

The refusal of a linear narrative is less an aesthetic choice than a necessity born out of the events that constitute an existence, Shahrzaad’s but also the film’s (see this interview with the filmmaker). Out of encounters and situations come a multiplicity of intertwining tales and viewpoints that contribute to make sense of both Shahrzaad’s life and the film. What matters however, is not so much the direction of these associations, but the intensities they convey, the power they exhibit. Likewise, sex, class, and politics, the blocs that constitute the points of articulation of these existential associations, are present but are never made into the matrices that generate a full story, or even the thousand tales the film envisages. Not even the violence that these blocs suggest is made to stand as an explanatory trope.

Someone might ask how this multiplicity is held together in the film in such a way as to generate power rather than chaos. The answer is poetry.

A film made of poetry

Poetry opens and closes Shahrzaad’s Tale, and recurs throughout the film. But it is more than poetry as content, it is poetry as form: the film is made of poetry. The assemblage of images, sounds, and words that make it up articulate that movement between warranted and frustrated expectations that linguist Roman Jakobson considered as the specificity of poetry: the play of repetition and difference.

The film has a marked metonymic rhythm: parts stand for wholes that are never quite accounted for. One does not really get the full picture about Shahrzaad, but perceives aspects of her through a set of ever deferred pleasures: a hand on a dial, an interrupted conversation, an elbow emerging from a bench, a house for a village, a clip for a movie we will never see.

The most eloquent example of this dissociative poetic process is the body of Shahrzaad: hands, eyes, hairs, thighs, but most of all the scars, taking a life of their own. Each body part is endowed with the power to move by itself, sideways or forward, overwhelming the screen in the dance scenes, or piercing it with gazes. In several sequences, the eyes of Shahrzaad look into the film in the process of its making, not to construct herself as an actor, to see herself as a self, but instead to challenge the very possibility of a story—to challenge the possibility of the filmmaker taking over the story from her. While evoking pleasure (sexual or otherwise), Shahrzaad’s body parts weave together the force of desire and the impossibility of a full body.

Deferred pleasures never quite find a linear resolution in Shahrzaad’s Tale. Poetry of suspension: the dots of ellipsis that Shahrzaad often uses in her poems, the wanderings of a leaf across a terrace –the camera follows these suspended movements, as if working against an idea of time (but also of life) as sequence, searching instead to express a sense of existence subtracted, albeit temporarily, from the demands of explanation. It is a suspension that hints at a delicately strong resilience, a dance of movements and counter-movements, what one could name the power of poetry.

When suspension gives way to the next shot, the montage of Shahrzaad’s Tale weaves these metonymic associations via a set of elements that echo Persian poetics: the already mentioned body parts (hands, eyes, hairs), natural elements (water, trees, clouds, sky) and landscapes (garden, desert, village). The film scrambles these poetic materials along a modernist line that not only expands their scope (to body parts the thigh and buttocks are added, to natural elements the car, to landscapes the city) but also marks a disjuncture, most notably in the case of the garden.

Supposed to be the site of fertility for the poet, and the very embodiment of life– as per the poetic tradition and Shahrzaad own verse: shâ‘er boghçe-ye zendegi ash bârvar ast, fruitful is the garden of a poet’s life– the garden instead appears in the film as a garden of stones hanging from dead trees, where Shahrzaad wanders aimlessly and recites verses in the wind that blows through the microphone. The materiality of these colors, sounds and shapes intertwines with virtual references. The garden of stones refers to the history of Iranian cinema, since this is Parviz Kimiavi’s garden, but inevitably also to Fourgh Farrokhzad’s poems. Poetry is always made of poetry, but as with the best verses, one does not need to be a cinephile to grasp the density and the beauty of these images.

The Experience of Poetry

Shahrzaad’s Tale is a film about the conditions under which poetry can be experienced in contemporary Iran and elsewhere. While the film is made of poetry, poetry in the film does not offer existential redemption and, contrary to many national and international contemporary interpretations, poetry is far from being the universalizing modality that recomposes a fragmented human multiplicity into a higher whole. Poetry is no salvation, no alternative, no safe ground. On the contrary, Shahrzaad’s Tale is an account of the perils that poetry is always exposed to, and foremost of the risk of appearing artificial and superfluous. Nowhere is this more evident than in the encounter between Shahrzaad and the small group of young women summoned to meet and work with her on their poetry and acting.

Nowadays in Iran and elsewhere there is a tendency to take poetry as a sign of the self, as an expressive modality that accounts in intimate, and true ways for the existential dimension of subjectivity. In this configuration, poetry is taken to be both the evidence for these affective states, as well as the cure, or at least the expression, the sign of an experience. As every cure, this combination of poetry and self is also an easily marketable commodity, something that is supposed to offer a quick experience of a true life, a true “Iranian” life.

In Shahrzaad’s Tale the young women, and especially a woman dressed in blue, repeatedly use the term ehsâs (feeling, sensation) to describe emotional states, and relate them to poetry, often to express malaise or suffering—Shahrzaad’s suffering and their own. But instead of capturing this suffering and turning it into a tale, or at least an interpersonal connection, the young women’s acts and words signal the impossibility of experience, the impossibility of making something meaningful, something that lasts beyond a fleeting affective agitation.

There is an expectation to feel, to recognize and be recognized by Shahrzaad, and poetry is seen as the means to this end. But poetry, rather than closeness and intimacy, produces distance and rage, it becomes a sign of the inauthentic. Whatever these women say they do in their lives appears inauthentic: singing, pilates, engineering; none of these efforts and actions seem to transform into meaningful experiences. Their signs of affection for Shahrzaad and their complementary expressions sound hollow. Penned by one of the women on a thank-you card she hands to Shahrzaad along with an embarrassingly exuberant vase of flowers, a quote attributed to Che Guevara –“being happy is the only revenge one can take in life”– rather than revolution, encapsulates the vacuity of a consumer culture that has erased the power of words.

In stark opposition to this poetry as self stands Shahrzaad, who in a scene of confrontation with the young women, denies that poetry is the embodiment of feelings, and with critical acumen foregrounds the opposite idea. Poetry is an act of separation from feelings, she says, adding that feelings in poetry are a sign of failure or a technical issue. Shahrzaad always answers: “no!” to the young women’s suggestions. Her critiques, her sarcasm, and her rage might seem to be signs of her own instability, but also show how impossible it is for these women to feel something, and even react to Shahrzaad’s provocations. As the woman in blue says, she is not offended at all by Shahrzaad’s insults. The young women become a spectacle, material for a film – darin? “Do you have them in the frame?” says Shahrzaad, looking into the camera and taking over the film with a grin.

This revenge of experience, this response of the old against the young, of the working class against the bourgeoisie, of the artist against society, against the state, but also against the filmmaker is grounded in a power to persevere, a resilience that is beyond good and evil and that is both active and reactive. This is, what I would call “poetic wisdom” or “poetic filming.” Shahrzaad’s Tale runs counter to visual narratives that offer stereotypical views of Iran, but also to narratives that, in an opposite but parallel move, pretend to offer “truer” perspectives on what Iran is “really” like by insisting on revealing the hidden side of things, by making sense of Iran and its people through stories. Each film produces its own audience. In countering these two dominant forms of contemporary representation, Shahrzaad’s Tale envisages a viewer that can perceive the power and necessity of poetry for existence, understood here as the power of not needing to make sense of the absence of stories.

In order for the film to reach its audience, these viewers might have to get together with other viewers and organize screenings and conversations. Such is the nature of film distribution in this time and age, but such is also the nature of powerful films (and poems): to assemble images, sounds, words and people.