The following article is part of a series featuring items from the Ajam Digital Archive. The Ajam Digital Archive focuses on twentieth century Persianate Life. If you are an academic interested in writing a similar piece, email us at info@ajammc.com. If you would like to contribute to the Archive, see here.

Popular narratives of modern Iranian history, particularly its religious history, hinge around the Islamic revolution of 1979, painting it as a natural outcome in a struggle for power between the Shah and the religious classes. This obscures the many religious worlds and trajectories that existed before the Islamic revolution and flattens our understanding of religious life under the Shah.

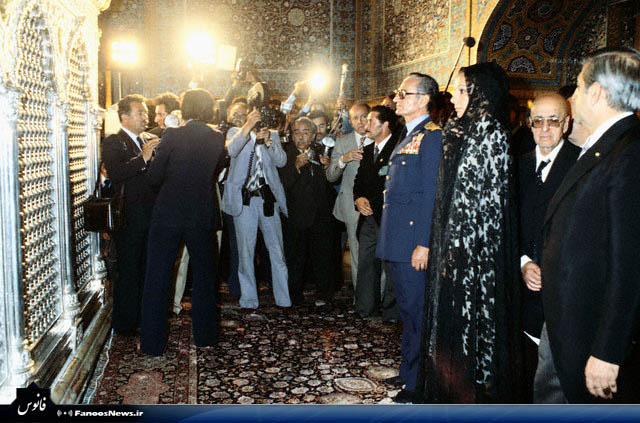

While the Pahlavi monarch, Mohammad Reza Shah, is remembered as a Westernizing ruler, he also presented himself as a Muslim king. He went on Hajj, the annual pilgrimage to Mecca, incumbent on Muslims to perform at least once in their lifetimes and undertook other minor pilgrimages around the Islamic world, including the pilgrimage to Mashhad in eastern Iran.

He saluted when he heard the call to prayer and began Nowruz, the Persian New Year, with a ceremony featuring a prayer and sermon by leading religious authorities. And he gave his sons, the heirs to his throne, names that honored the patron saint of modern Iran, the eight Shi’a Imam buried in Mashhad, as well as his father, Reza Shah’s name: Reza and Ali-Reza. In a waqf, or an institutionalized religious donation, to the shrine of the 8th Twelver-Shi’ite Imam Reza in 1948, he called Iran “an Islamic country” and made numerous references to the Qur’an and Hadith. He praised God’s greatness and thanked Him for allowing him to strive so that “the sun of the Shari’ah of the Best of Messengers rises higher.”

In turn, many of the ulema expressed their affection for the King openly. The ulema played key roles in multiple rituals of the court, many of which included praise and prayers for the king. They were involved at his crowning in 1967, as well as the yearly celebrations of Nowruz.

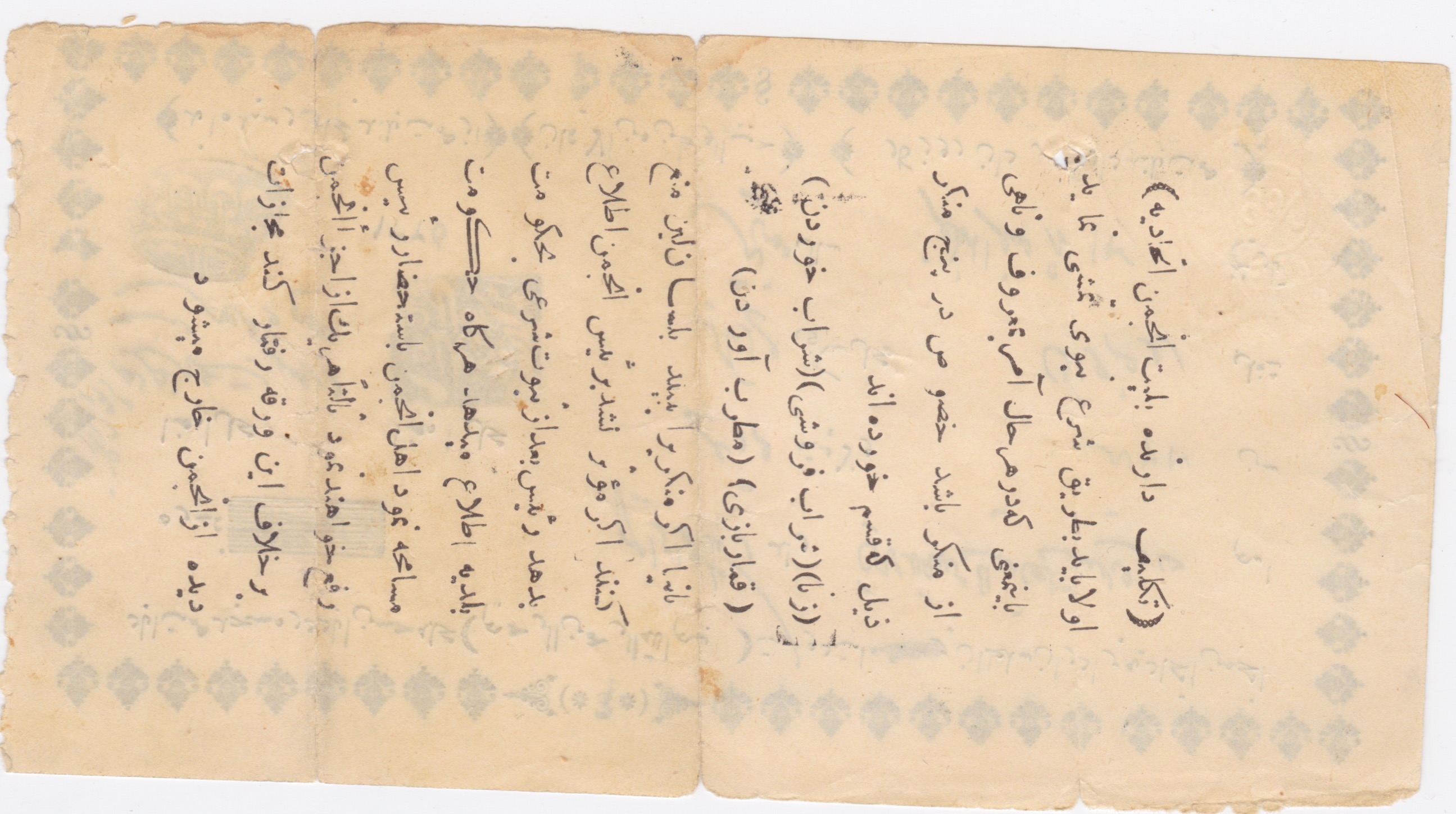

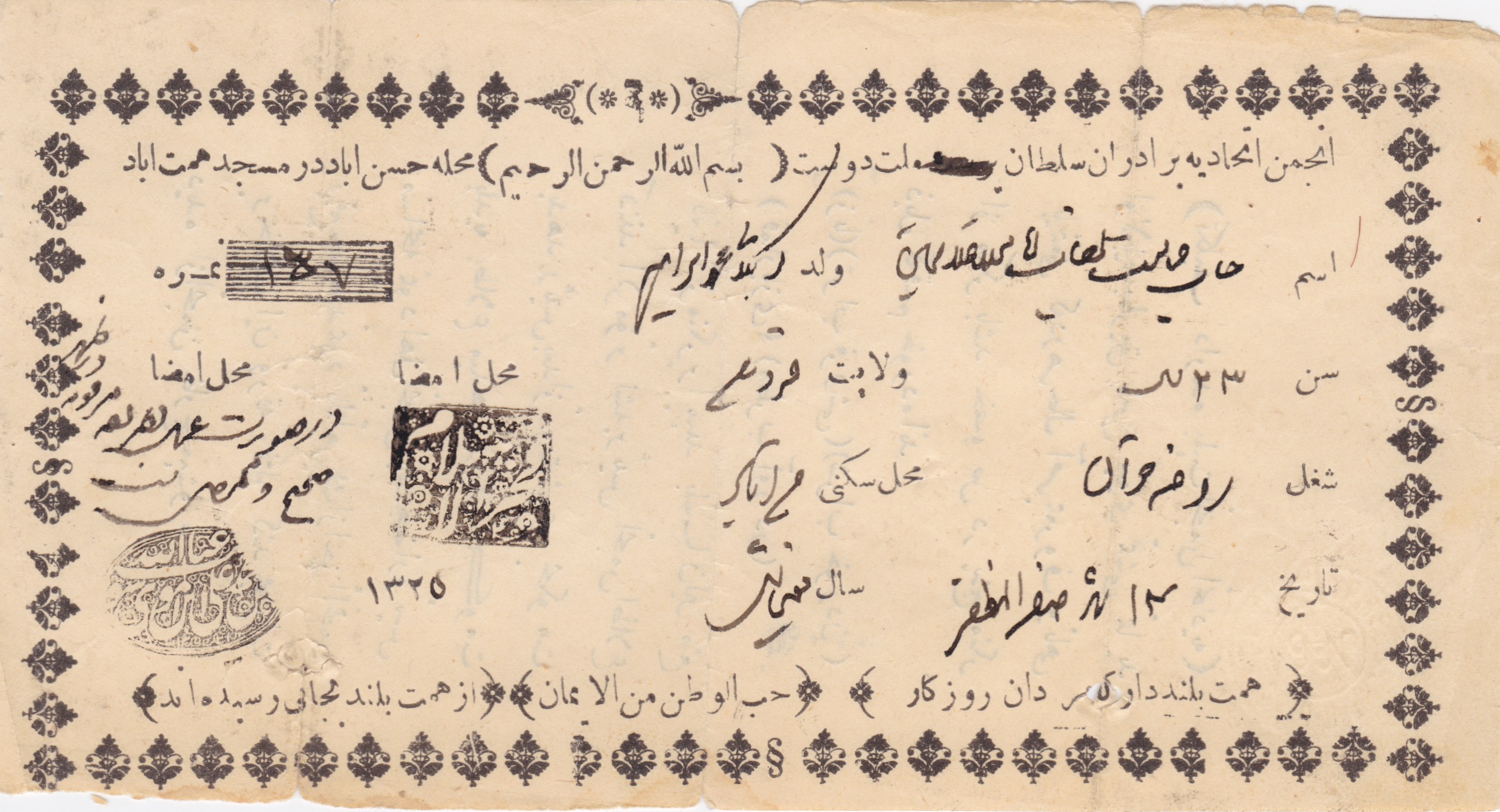

Some ulema took their devotion a step further by partaking in unions, from 1946, called “The Organization of the Brothers that Worship the King and Love the Nation.” The goal of this union, as stated on the back of its membership card, is to “walk upon the Shariah of Muhammad” and command people to good and warn them in reference to five evils: fornication, selling alcohol, drinking alcohol, gambling, and inviting motreb, or musicians and entertainers. Union members agreed to tell those engaged in these evil acts in a lenient way to stop, and if they were unsuccessful, they must contact the union director and ask their local government for help. Tellingly, the word “worship” has long been crossed out on this member’s card.

None of this is to deny the Shah’s steps towards secularizing Iran or limiting the presence of religion in the public sphere, but the image of a staunch secularist, pushed by proponents and opponents of the revolution alike, elides the complex role of Islam in the Shah’s self-presentation. While he showed himself as a Western, modern king to the international community, he still invoked the the rituals of Islamic kingship, with their ancient roots, in his performance of kingship at the local and provincial levels.

This performance was upped at times of turmoil, like in the build up to the 15 Khordad Uprisings (June 5, 1963) in Iran, when Khomeini used the advent of Muharram and Ashura to criticize and demonize the Shah. Khomeini’s rhetoric reached its peak on June 3rd when he likened the Shah to Yazid, the ultimate villain in Shi’i Islam. On the day following Ashura, the newspapers featured photographs of the Shah’s court in mourning to counter allegations that the Shah may have been anti-Islam. Of course, these photographs did little to convince the public. Major protests took place the next day following Khomeini’s arrest, resulting in hundreds of casualties and arrests.

The radio also took part in this performance. During the month of Muharram, the radio broadcast segments of the royal mourning ceremony, featuring some of the best preachers and dirge singers in the country. The preachers and orators all praised the Shah and his family as protectors of Islam. Thanks to the Ajam Digital archive, we are able to share recordings of the court’s Ashura ceremonies:

The state radio also aired recordings of the processions that occurred on Ashura day near Tehran’s bazaar, projecting one of the main yearly rituals of the capital into the airwaves of the country:

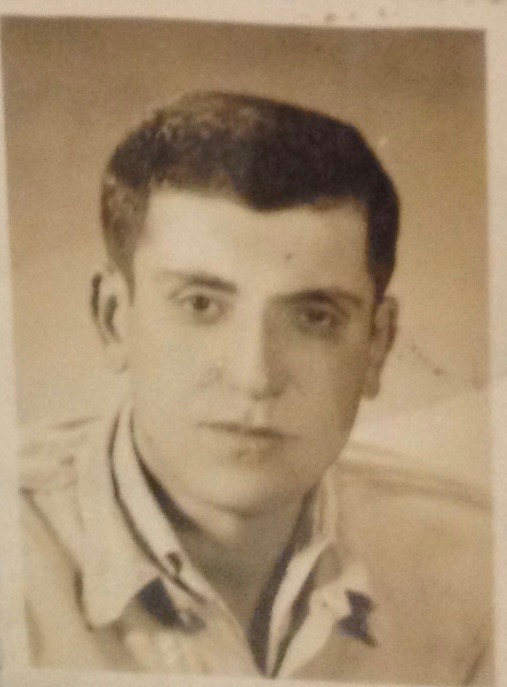

The Ajam Digital Archive, crowdsourced and aimed at social life in the 20th century Persianate world, offers us a gateway into the complex worlds of pre-revolution religious life in Iran. These previous radio recordings, as well as a host of other recordings, were made by a young curtain maker named Mohammad Taqi Noei-Asgarnia. Born in Tehran in 1938, Noei-Asgarnia loved new technology. His passion led him to purchase a Korting MT-153 Reel to Reel tape recorder, one of the first portable recorders on the international market. He not only used his recorder to preserve audio from the radio, but he also recorded the voices of his family, friends, and neighbors.

In files that will soon be added to the Ajam Digital Archive, we see more of Noei-Asgarnia’s interests. While he lived in Tehran, he also had relatives in Qazvin, a city about 150 km/93 miles north of Tehran. During Muharram, he visited his family and participated in the ritual mourning, whose melodies and rhythms filled the streets of the city. One year in the early 1960s, he took his Korting recorder with him.

These recordings are mostly from Sham-i Ghariban, “the Night of Strangers,” which marks the night after Ashura and the martyrdom of Husayn. He recorded the processions that marched in the streets, together with their drums and flutes (which have now been replaced by trumpets), as well as the preachers and their crying congregants. In the recordings, one can hear the preachers’ prayers for the “King of Islam,” Muhammad Reza Pahlavi, as well as prayers for his soldiers, referred to as “the Mujahideen of Islam.” These prayers also draw on Iran’s recent history, such as its occupation during WWII, asking God to “protect our honor from the claws of foreigners.”

But beyond politics, these recordings offer a window to the social life of average Iranians away from the center of the Shah’s modernization and Westernization projects. They preserve the dialects of Qazvin in the 1960s, which, like most provincial dialects in Iran, is already close to extinction. They highlight the preferred styles and performance of poetry in the 1960s and early 1970s. We can hear the cries of men and women, the clattering of tea cups that were distributed as nazri, a devotional offering for the sake of fulfilling a need. They even include exhortations from grumpy preachers to women who uncovered their faces, even though the face veil had been falling out of use since Reza Shah’s ban of all veiling three decades earlier.

These recordings from Sham-i Ghariban were all made in the Hussayniyih-yi Aqa Seyyid Jamal-i Razavi (حسینیه آقا سید جمال رضوی), a religious center devoted to Muharram and Safar rituals, which is still in operation:

One of the important features of these Muharram recordings is the overwhelming presence of women at the gatherings and their participation in the chorus:

Noei-Asgarnia also recorded private gatherings, which would not have been open to most visitors in the city:

Through recordings like these, we have access to the religious life of non-elite Iranians, whose perspective is lost in government archives and official narratives that privilege elite sources. By providing us with a local perspective, we see how the rituals of Shi’ism, the ideology of Islamic monarchy, and new media technologies all interacted and shaped both the public and private spheres.

If you or anyone you know has similar materials from the 20th century in the Persianate world, please consider contributing to the Ajam Digital Archive.