The following is a guest post by Gelare Khoshgozaran, an interdisciplinary artist and writer working across film and video installation, performance and writing. She is the co-founding editor of contemptorary.org.

In this piece, she discusses the underpinnings of her work “Medina Wasl: Connecting Town,” which is currently on display at Made in L.A. 2018. This piece was commissioned by X-TRA and first published on June 12, 2018. The original is available here.

No one knows for certain how many Iraqis have died as a result of the invasion 15 years ago. Some credible estimates put the number at more than one million. You can read that sentence again. The invasion of Iraq is often spoken of in the United States as a “blunder,” or even a “colossal mistake.” It was a crime. Those who perpetrated it are still at large. Some of them have even been rehabilitated thanks to the horrors of Trumpism and a mostly amnesiac citizenry.

—Sinan Antoon, “Fifteen Years Ago, America Destroyed My Country.” The New York Times, March 19, 2018.

The term “Middle East” originated in the British India Office in the 1850s. A turbulent time of colonial expansion and war. A decade also marked by The Great Exhibition (The Crystal Palace Exhibition) of 1851 where the world was arranged to be presented, perceived and consumed under a new exhibitionary order. The term “Middle East,” however was not common until 1902 after Alfred T. Mahan used it in his essay “The Persian Gulf and International Relations,” published in the National Review and later in his book, Retrospect and Prospect: Studies in International Relations, Naval and Political.

A. T. Mahan, Retrospect And Prospect: Studies In International Relations, Naval And Political (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1902). https://archive.org/details/retrospectprosp00maha.

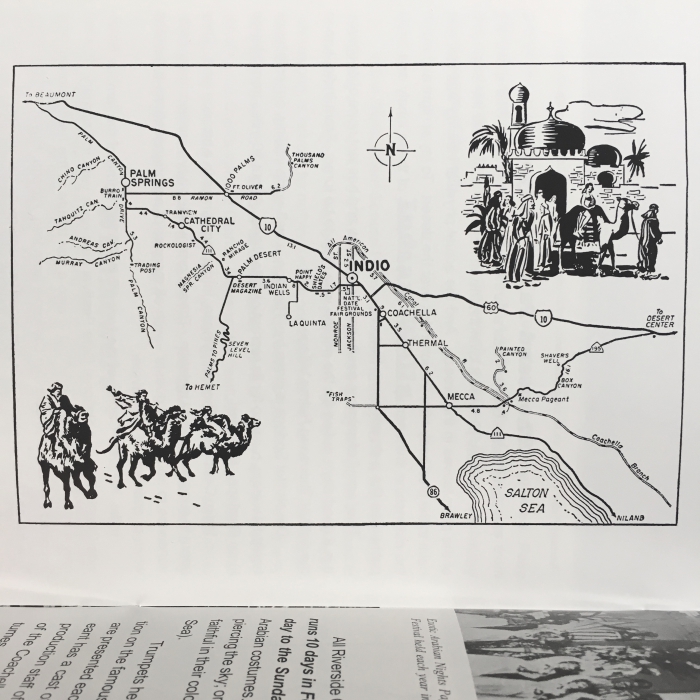

1902 was also the year the date industry was born in California. Much like the origin of the term “Middle East,” it is difficult to pinpoint the exact year dates were cultivated here. Cultivars from the Middle East and North Africa were introduced to California as early as the 1890s after extensive research travels to those regions to study the climate and date cultivation. The similarities between the climate of the California desert and that of the Arabian and Sahara Deserts did not go unnoticed by the visionaries.

Historian Sarah Seekatz reminds us, “These trips to the Greater Middle East for the date palms provide some of the first links between the two regions. The interactions these government scientists and local entrepreneurs had with the people of the Middle East are extraordinary and they speak not only to the complicated geopolitical realities of the area but also to American assumptions of racial and scientific superiority. One Los Angeles Times article about the growing date industry, published in 1921, suggested that the ‘American scientific culture has far surpassed the Orient in date possibilities. In fact in the hot sand around Indio and Coachella the date has come to surpass anything of which the dozing Orient ever dreamed.’”

The marketing of date as an industry worthy of investment required a fantastical spectacle as the context in which the exotic fruit would be introduced. The early 20th century Date Festivals led to the post-war Riverside County Fair and the Coachella Valley Date Festival with Arabian Nights Pageants, genies, harem girls and camel rides—an Orientalist tradition that continues today. The 2018 Riverside County Fair and Date Festival closed on February 28.

The nightly Arabian Nights Pageant began on the Magic Carpet Stage as a godly male voice told the legend of Scheherazade; it followed with the music of the different branches of the military in honor of active duty members and veterans in the crowd, as a US flag, the size of a small building, covered the right side of the Shah’s castle on the stage. The night continued with “Walk like an Egyptian” style dances in Orientalist costumes, and culminated in the celebration of Queen Scheherazade andQueen Jasmine scholarship awards granted to students from the county who work as “ambassadors of goodwill” during the fair.

In the desert where beheaded date palms are intimately rooted in seeping crude oil, in “the dozing orient,” a different politics is being sown. In September 1980 Saddam Hussein announced that Iraq abrogates the 1975 Algiers Agreement, declaring full sovereignty over the Shatt al-Arab and restoring its legal position to the pre-1975 status. Iraq’s invasion of Iran led to an eight year war.

In the end, while both sides claimed victory, Iraq failed to annex the Iranian province of Khuzestan and bolster Arab separatism; Iran failed to topple Saddam Hussein and export its revolution to the neighboring country. Losses have been reported up to $620 billion dollars and the death toll as high as a million; which includes 95,000 Iranian child soldiers between the ages of 16 and 17, but some even younger. Thirteen year-old Mohammad Hossein Fahmideh became the ideal of Iran’s martyrdom for decades to come.

Soon after the invasion of Afghanistan, the US military prepared multiple mock villages of Afghan and Iraqi towns to prepare the troops for “insurgent warfare.” The “archipelago of Middle Eastern towns” in Stephen Graham’s words, were built 7,777 miles away from Basra, Iraq in Southern California, based on “the realities awaiting the soldiers outside Baghdad and Mosul and Fallujah.” Each combat town used to change names based on the operation or city the troops were training for. After a few years, with the expanding number of battles and multitude of destinations for the US troops, the army no longer changes the name of these towns. Instead the entire area at the National Training Center at Fort Irwin is referred to as “the Box,” implying sandbox.

A New York Times article from 2006 reports: “Arab-Americans, many of them from the Iraqi expatriate community in San Diego, populate a group of mock villages resembling their counterparts in Iraq. American soldiers at forward operating bases nearby face insurgent uprisings, suicide bombings and even staged beheadings in underground tunnels. Recently, the soldiers here, like their counterparts in Iraq, have been confronted with Sunni-Shiite riots. At one village, a secret guerrilla revolt is in the works.”

These villages are arguably the immersive and contemporary counterparts of the colonial villages on display at the world fairs and The Great Exhibition as far back as the mid 19th century, realized by the military. In “Orientalism and the Exhibitionary Order,” Timothy Mitchell writes:

“By the last decade of the nineteenth century, more than half the descriptions of journeys to Europe published in Cairo were written to describe visits to a world exhibition or an international congress of Orientalists. Such accounts devote hundreds of pages to describing the peculiar order and technique of these events— the curious crowds of spectators, the organization of panoramas and perspectives, the arrangement of natives in mock colonial villages, the display of new inventions and commodities, the architecture of iron and glass, the systems of classification, the calculations of statistics, the lectures, the plans, and the guidebooks— in short, the entire method of organization that we think of as representation.”1

Despite these sites being open to the public, however, the question remains: what bodies may gain access, passing the military’s clearance, to enter an army base for an art project? What bodies can afford the emotional expense of this visit? What does one witness at the site of one’s kin as the role-player in a simulated battle, thousands of miles away from the battle they escaped from; and upon whose return may begin the reorganization of representation?

This piece was commissioned by X-TRA and first published on June 12, 2018. The original is available here.