Fuchsia Hart is a Doctoral candidate in Oriental Studies at the University of Oxford. Fuchsia’s research is based on the material culture of Shi’ism in Iran, and she is particularly interested in shrine architecture and 13th-14th century lustre tiles. Find her on Twitter here: @FuchsiaHart

“When women come out of the bath they ought to dress in gay apparel, and if they have any engagement, they must first proceed to the house of their friend or lover. And if they meet a handsome young man on their way, they must cunningly remove a little of the veil which covers their face, and draw it off gradually, pretending “It is very hot, how I perspire…”

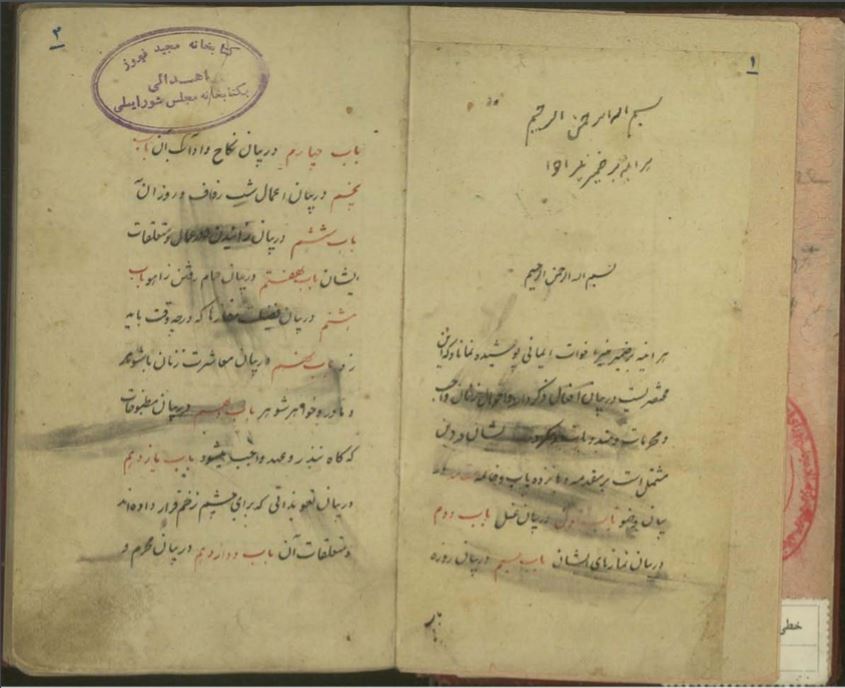

Thus are the instructions given to Persian women on leaving the public bath in Customs and Manners of the Women of Persia and their Domestic Superstitions, a late 17th century text by the cleric Aqa Jamal Khwansari (d. 1710) originally titled ‘Aqa’id al-Nisa’ (Beliefs of Women), but also known as Ketab-e Kulsum Naneh (The Book of Kulsum Naneh). In 1832 a translation by British surgeon, orientalist, and painter James Atkinson (1780-1852) was published in London by the Oriental Translation Fund (OTF). Atkinson’s version of the work is divided into twelve chapters, each giving advice and rulings on every-day domestic and religious matters such as prayers and fast-days (chapter II), the nuptial night (chapter V), charms (chapter VIII), and gossips and intimates (chapter X), accompanied by his copious footnotes and preface.

In his preface to the work, Atkinson writes that although the work may resemble a ‘grave’ ‘code of laws’, it is actually a humorous description of ‘Persian life behind the curtain’. However, what Atkinson does not appreciate is that, while the original text may appear to be a light-hearted, satirical depiction of everyday life, Khwansari’s original work was actually a comment on and implicit criticism of the unorthodox practices perpetuated by women in the late Safavid period.

Aqa Jamal Khwansari was a prominent cleric and religious scholar of the late Safavid period. A pupil of his father, Aqa Husayn Khwansari, and of Muhammad Taqi al-Majlisi (Majlisi al-Awwal), he was active at a time of increased Safavid Imami Shi’i orthodoxy in Isfahan, instituted largely by his peer Muhammad Baqir al-Majlisi (Majlisi al-Thani). ’Aqa’id al-Nisa’, described by Khwansari as ‘a treatise for the instruction and edification of the female sex’ based on the knowledge of ‘five accomplished females’ and their two other female companions, remains his best-known work. While the work certainly was intended to be amusing, it also held deeper intentions.

Khwansari’s sardonic tone is intended to criticise the behaviour of women, while also drawing attention to the inefficacy of the Persian language religious manuals circulating at the time he was writing. Considering this intention, we must question whether the seven women providing the ‘instruction’ were indeed real figures. While we know of female authorities on religious matters in 17th century Isfahan, often the daughters or wives of clerics, these characters are closer to ‘old wives’ and their names, such as Kulsum Naneh and Shahrbanu Dadeh, suggest they are merely caricatures.

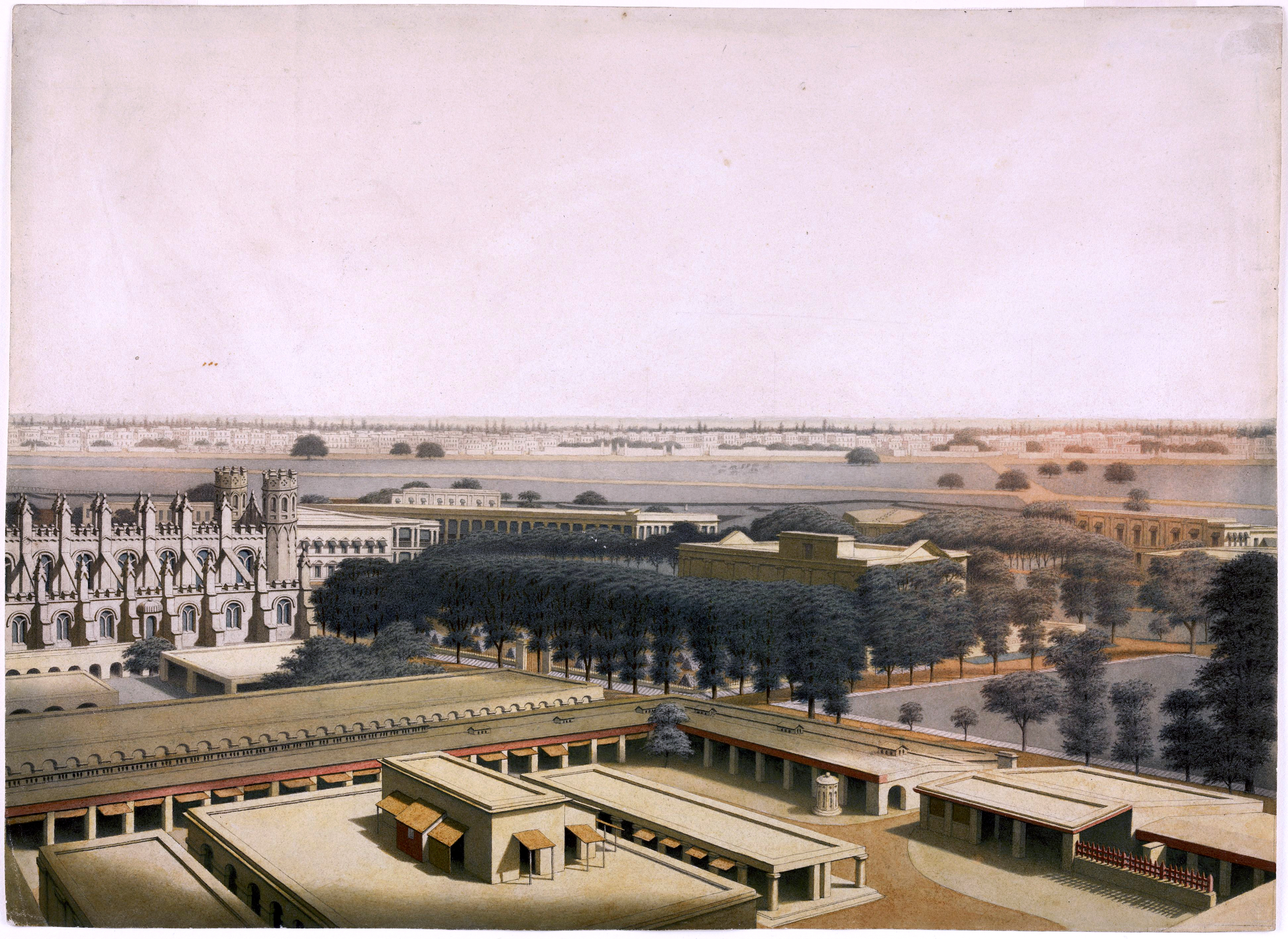

James Atkinson, born in County Durham, north-east England, was a notable orientalist who spent much of his career in what is now India and Bangladesh. After completing his studies in Medicine, he joined the East India Company, first as a medical officer on board ship and then as assistant surgeon based near Dhaka. He quickly developed good Persian language skills and by 1818 he occupied the deputy chair of Persian at Fort William College, Calcutta (now Kolkata). Atkinson went on to produce a number of translations from Persian, most notably an abridgement of Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh in verse and prose, also published in 1832 by the Oriental Translation Fund.

Atkinson states his own intentions in his preface. ‘The oriental scholar who is devoted to the more abstruse labours of the Persian sages, may look with disdain upon productions like this of a less formidable calibre – upon efforts of a light and sportive kind, – and think them unworthy of notice’. He is introducing this work not as a heavy, serious piece of literature, but something of a lighter naturea and he goes on to admit that ‘the domestic customs and superstitions of every country are for the most part absurd or trivial, and in the East often extremely ridiculous’ but he sees the merits of the study of such texts. He writes that as they ‘[form] part of the history of the human mind, in its social and moral bearings, they cannot be totally uninteresting’.

The main benefit of Women of Persia, according to Atkinson, is that it will inform the English reader of ‘the real situation of women in the East’. He explains that most in England will think of the harem as little more than a prison. But, he emphasises, ‘the Persians themselves look upon their women as virtually invested with more power and liberty, and greater privileges, than the women of Europe’. We can infer that, from his reading of Khwansari’s text, Atkinson has grasped an understanding of the women of Persia, and the freedom they have, which counteracts what he believes to be commonly held misconceptions.

A tradition given in chapter V supports this: ‘When the husband is introduced into the bridal-chamber, he is seated by [the bride’s] side. The right leg of the bride is place upon the left leg of the husband, and her right hand is placed upon the hand of her husband, to shew [sic] that she ought always to have the upper hand of her spouse.’

Similarly, chapter VII opens: ‘This chapter embraces the conduct of husband to wife, and wife to husband. That man is to be praised who confines himself to one wife; for if he takes two it is wrong, and he will certainly repent of his folly.’ And later: ‘He should give [his wife] money without limit: God forbid that she should die of sorrow and disappointment!’.

– – –

The depiction of women, in text and image, has long been a male preoccupation; the depiction of the women of the ‘East’ by the men of the ‘West’ even more so. We can go as far back as Herodotus’s description of a Persian woman and his portrayal of the influence wielded over Achaemenid king Darius I (r.522-486BC) by his wife Atossa. Herodotus describes Atossa using her influence over Darius to persuade him to go to war with the Greeks so she can enjoy maidservants from the Greek states. Women of Persia is a particularly interesting case, as the representation of women is formed in two stages, by two very different men – Khwansari and Atkinson – with two very different aims.

In late 17th century Isfahan, Khwansari is deep in the midst of the creation of orthodoxy. Majlisi al-Thani has produced his Hilyat al-Mutaqqin (The Adornment of the Pious) in 1081/1670. A key manual for orthodox practice of Shi’i Islamic rites and rituals, it was produced in Persian to facilitate maximum impact on the general populace of Isfahan and the wider Safavid realm, in order to aid the establishment of a homogenous religious environment. ‘Aqa’id al-Nisa’ mimics such texts, using their layout according to rite and their religio-legal terminology such as wajib (obligatory), mustahab (recommended), and sunnat (traditional). Khwansari may even be mimicking this genre in order to criticise it, and perhaps show its inefficacy.

Atkinson, on the other hand, is writing two centuries later at the height of Empire and Orientalism. 1832 itself sees French painter Eugène Delacroix’s seminal visit to North Africa; a visit which will inspire, and provide material for, some of his greatest later works in the Orientalist style. Women of Algiers in their Apartment will be put on display for the first time in 1834. References to the ‘Orient’ and its women pepper both prose and poetry of England as European audiences are made increasingly familiar of the exotic world of the ‘East’ through travelogues. Depictions of women were central to these. Set against this cultural backdrop, Women of Persia could be seen as innovative, as Atkinson is aiming to give a glimpse into the reality of the lives of real women in Iran. However, his mission is only partly successful, as it seems that Atkinson did not have a full grasp on Khwansari’s own mission.

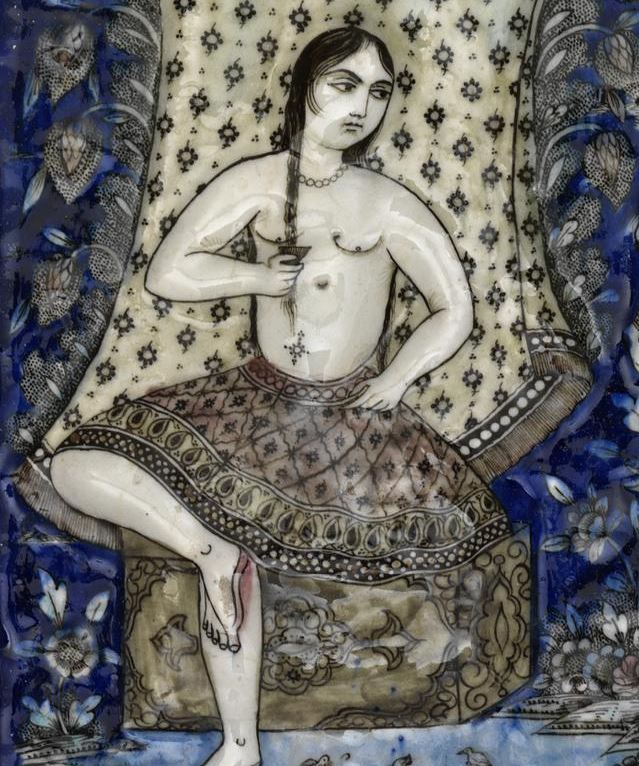

First of all, while Atkinson is aiming to break down misconceptions, he himself perpetuates aspects of the received wisdom of the time. In a footnote on the public baths, he writes that women spend time:

… curiously staining their fair bodies with a variety of fantastic devices, not unfrequently with the figures of trees, birds, and beasts, sun, moon and stars. This sort of pencil-work spreads over the bosom, and continues down as low as the navel, round which some radiated figure is generally painted. All this is displayed by the style of their dress, every garment of which, even to the light gauze chemise, being open from the neck to that point; a singular taste and certainly more barbarous than becoming.

The two clichés of ‘Western’ representation of ‘Eastern’ women are the subjugated wearers of the veil and, in contrast, the exoticized, eroticized odalisque, such as the one often depicted by Delacroix and, earlier and most famously, by another French painter, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres in his 1814 Grande Odalisque. The odalisque (from the Turkish odalık, meaning chambermaid) epitomises the perceived sensuality of the oriental harem. Even though Atkinson aims to counter the former cliche of subjugated woman, he reinforces the second, with all its perceived barbarity.

While his depiction of the women is sexualised, it can be argued that Atkinson’s text is, in some ways, less salacious than ‘Aqa’id al-Nisa’. Khwansari’s allusions to same-sex relationships are excluded in the English text. Kathryn Babayan’s work on khwahar-khwandegi (sworn sisterhood) has demonstrated how these practices, which Khwansari discusses, are formed not only on bonds of platonic friendship but on amorous, sexual relationships too. It is impossible to know, however, whether this is because Atkinson failed to grasp the connotations of certain Persian words, or whether he took against such undertones.

But could Atkinson appreciate the wider context, meaning and aims of the work he was translating? Did Atkinson know about the religious fervour which had swept Isfahan in the 17th century? Probably not. The absence of comments on the original author, manuscript, or socio-political context, suggests that Atkinson had little knowledge of the milieu in which Khwansari was writing. It is likely that he was even unaware of the original author of the text and the date of its creation. We do not know what manuscript he used to produce his translation and it is possible that it was neither dated nor included the original author’s name. His own perception, and knowledge contemporaneous women in India, Iran and Europe, frame his translation. In this way, Atkinson’s work is not only a translation, but also an interpretation. His copious footnotes often refer to women living in Qajar Iran – notes which will influence the way the reader imagines the women central to the text. It is not only the language of the work which changes but, of course, its audience too, as well as its purpose.

Atkinson’s aim of subverting the false picture which his countrymen might have regarding the standing of women in Iran could be commendable, but we can see that ‘Aqa’id al-Nisa’ might not have been the right text with which to attempt this. Atkinson describes the text as a jeu d’esprit, and does not comment on the potential role of the original text as a means for soft repression of women. Khwansari’s use of humour is not purely to elicit merriment – he is drawing attention to, and mocking, the unorthodox practices to which women continue to adhere, such as flirting with handsome young men as we saw in the opening quotation, despite centralised efforts to impose practices in accordance with Safavid Imami Shi’i law.

Atkinson’s comment that the work ‘presents a view of domestic life, not as it ought to be… but as it is’ is, perhaps unwittingly, the closest he gets to the reality of the text. Khwansari’s work presents a view of women not as they ought to be according to Shi’i law, but as a caricature of how they are – from his own clerical-scholarly point of view.

We must, therefore, be cautious about using either Atkinson’s or Khwansari’s text to illuminate the lives of Safavid women. While it would be expected that satirical texts like ‘Aqa’id al-Nisa’ respond to embodied practice, it is difficult to ascertain to what extent the ‘traditions’ given by Khwansari’s ‘seven wise women’ represent reality. It is unlikely that all women will have always had the upper hands over their husbands and, likewise, they will not have always been the pious wives recommended in religious manuals. The truth of the matter is much more nebulous, just as the quest for orthodoxy itself often is.

Further Reading

“The Aqa’id al-Nisa: A Glimpse at Safavid Women in Local Isfahani Culture,” By Kathryn Babayan

“‘In Spirit We Ate of Each Other’s Sorrow:’ Female Companionship in Seventeenth Century Safavid Iran by Kathryn Babayan.