Kimia Maleki is a scholar of art history interested in historiography, archiving, and curatorial practice, especially as pertains to Iran. She received her MA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and her BA from the University of the Arts, Tehran.

Soon after the triumph of the Iranian Revolution in February 1979, Ayatollah Khomeini called for the removal of all symbols of the fallen monarchy. Deeming them remnants of a tyrannical regime (taghuti), he called for the nation to create symbols befitting the new revolutionary era. At the head of the list of symbols to replace was the shir-o-khorshid, the lion and sun emblem traditionally associated with the monarchy previously at the center of Iran’s national flag. A national competition was announced in spring 1979 for a new emblem, and eventually it was a design by architect Hamid Nadimi that won out, becoming Iran’s most prominent national symbol.

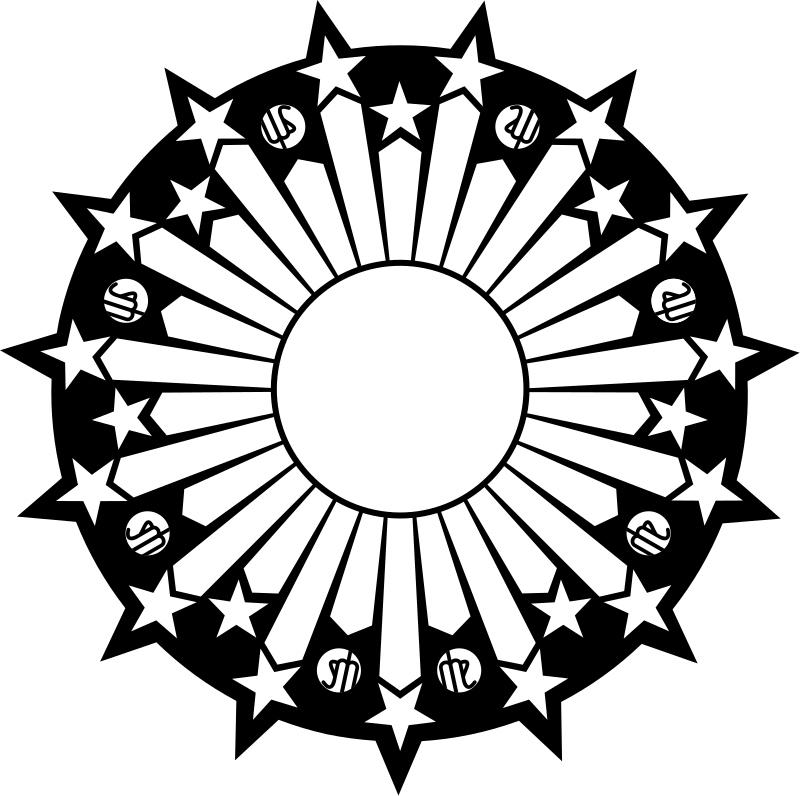

Iran’s flag is unique in many ways; most prominently, the Allāhu akbar (“God is great”) design at its heart resembles no previously-existing Islamic symbol (such as the crescent and star), but was instead created ex nihilo by an artist to accompany the novel idea it would crown: an Islamic Republic. In Iranian schools today, there are lessons about the colors of the flag – green, white, and red – but little discussion of how the lion and sun came to be replaced suddenly by the Allāhu akbar.

As an art student in Iran in 2009, I carried out an interview with Hamid Nadimi, then a member of the faculty of Architecture at Shahid Beheshti University in Tehran. Despite the flag’s prominence, Nadimi rarely agreed to interviews, so my interview was one of the few ever given about the winning flag design. On the 40th anniversary of the Iranian Revolution, I revisit our understanding of both the visual and conceptual aspects of the emblem of contemporary Iran, alongside an analysis of contemporary debates about the national flag and emblem.

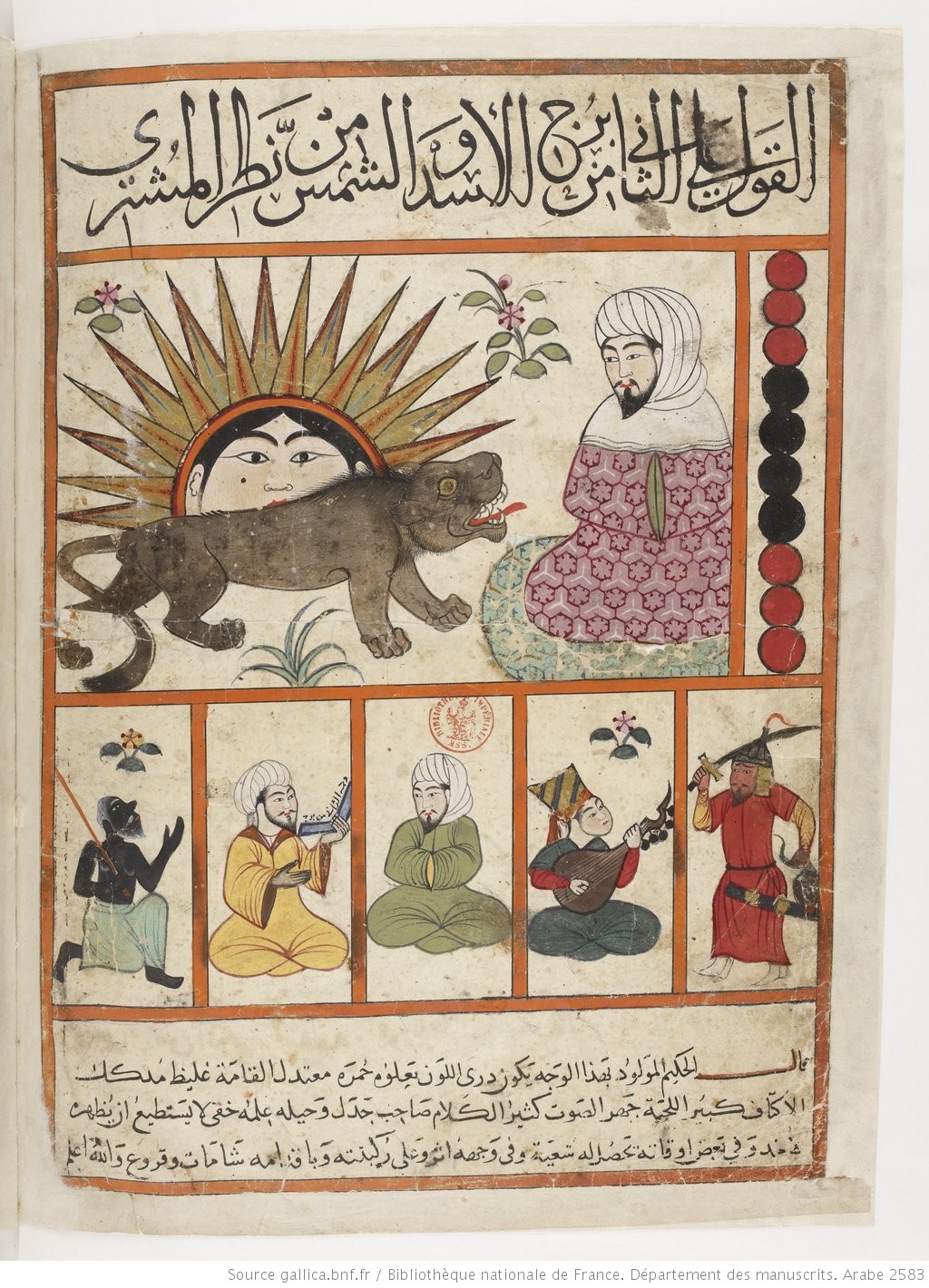

Sun and Lion: Symbol of Monarchy or Islam?

Nadimi’s emblem has always been a controversial one. While national narratives present it as holy and spiritual, there are wide-ranging discussions about whether the flag is appropriate or whether it should be replaced. While this is most prominent in the diaspora – where some who left the country after the Revolution use the previous flag as a symbol of opposition to the present government – the debate persists inside Iran as well. At its most basic level, this debate reflects disagreement about what the symbols of both the previous and the current flag mean. While the sun and lion is most often described as a symbol of monarchy, this is far from certain.

In spring 2014, Iranian president Rouhani’s senior advisor for ethnic and religious minority affairs, Ali Younesi, suggested an Islamic interpretation of Iran’s pre-revolution flag. During a visit to a Tehran synagogue, Younesi suggested that the sun and lion was not merely a monarchic symbol. Younesi argued that the lion was in fact a symbol of the first Shia imam, Imam Ali, and the sun was linked to the Prophet Muhammad.

This argument has historical roots; 20th century Iranian historian Ahmad Kasravi noted the connection between Imam Ali and the lion, and the double-bladed sword it holds is thought to be none other than the famous sword wielded by Imam Ali, the zulfiqar. However, the crown above the lion and sun on the flag – which was added first on coins and medals in the 18th century and then eventually to the flag during the Pahlavi era in the 20th century – altered the flag to be more in tandem with the Persian imperial state.

Younesi consequently suggested that the newly-elected Rouhani administration bring back the Lion and Sun emblem. He also proposed to replace the logo of the Red Crescent – the affiliate of the Red Cross in Muslim-majority countries – with the red Lion and Sun figure. (Under the Pahlavi dynasty, the red Lion and Sun was the only Red Cross affiliate in the world that used a national symbol instead of a religious one.) The reason for this request was to bring back the original Iranian and religious elements back into the sight of public.

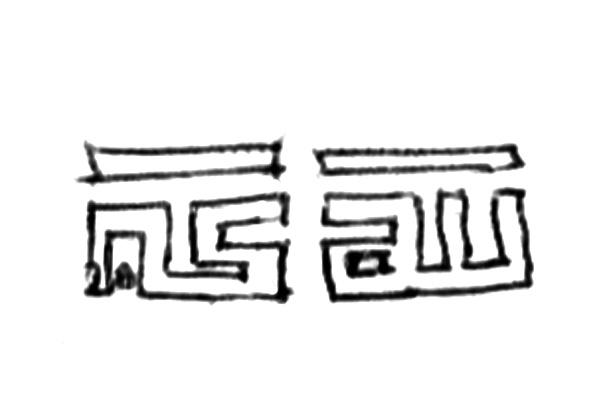

Since the 1979 Revolution, there has been a wide-ranging debate on the Iranian national flag. The most common complaint about the current flag is the lack of characteristics linked to Iranianness or Persianness. This is true especially in terms of language, with both the word Allah and the Kufic script reading Allāhu akbar on the green and red stripes being Arabic (The Persian word for God is “Khoda” or “Parwardigār”). One comment on an article about the Younesi synagogue speech, for example, noted that Iran is the only country in the world with a flag containing a language other than its official language. But discussion has largely failed to explore the meaning and concept of the current emblem and flag of the Islamic Republic of Iran.

The power of “flesh and blood”

Driving along Modarres Highway, one of the main routes connecting Tehran’s northern and southern ends, a giant flagpole appears out of the green hills of Abbasabad. Standing at a height of 150 meters, the flagpole is topped by a gigantic green, white, and red Iranian flag fluttering endlessly in the wind. In 2012 that Tehran’s former mayor Qalibaf began to install large-scale flags on several Tehran hills. The mission of the flagpole project was to emphasize “Azimat-i Hoviate-i Irani,” meaning “the magnificence of Iranian identity”. This phenomenon in recent years indicates a growing feeling of nationalism in the collective consciousness, after years in which the government emphasized the Islamic dimension of Iranian identity.

As novelist David Madden notes, “A flag flying in the wind can look so awesome that it has the power almost of flesh and blood, like a living organism.” At the heart of this power is the most vibrant aesthetic dimension: the colors. The meaning of the colors are widely known among the Iranian public: green stands for prosperity and is also the color of Islam, white is peace, and red is the color of the blood of martyrs who died defending the country.

On March 1, 1979, just weeks after the victory of the Iranian Revolution, Ayatollah Khomeini asked for the removal of the former regime’s symbols. Hashemi Rafsanjani, who was then was one of the core members of the Council of the Islamic Revolution, notes in his diary that there was no disagreement on the colors, but Ayatollah Khomeini wanted to change the emblem to represent the new Islamic country.

An open call for proposals was launched. After the first round, an emblem by Sadegh Tabrizi (1938-2017), part of the traditional painting school of Saqqa-khaneh, was selected. Currency and governmental papers were even published with this emblem, which has since been widely forgotten. For the emblem, Tabrizi designed a circle, probably representing a globe, with closed fists coming out of it on spears. Each iron spear is similar to the main vertical shape of the current emblem. The first emblem did not last long. It’s not clear why it was discarded; one possible reason it that it resembled a pentagram in certain respects, a symbol often associated with Satanism. However, the spears’ link to iron was retained in the version to come.

After Nadimi listened to the speech by Ayatollah Khomeini, he started sketching the emblem with three main concepts in his mind. He designed it to have both Iranian and Islamic characteristics, with the Allah meant to resemble a tulip and lotus flower – symbols in ancient Persia – and the color bands marked by Kufic script. Kufic was the first Arabic script, but Persians later created a form of maʿqelī or bannāʾī Kufic commonly used during Seljuk and Timurid Persia on architectural brick work, which the flag’s Kufic resembles. The emblem’s concept emerged from a section of Qur’an. During the days after the revolution he was struck by the Quranic Surah al-Hadid. It recounts three pillars of Islamic government: “book/scripture”, “balance” and “iron”. Or as Qur’an puts it: “kitab”, “mizan” and “hadid”.

سوره حدید، آیه ۲۵: لَقَدْ أَرْسَلْنَا رُسُلَنَا بِالْبَيِّنَاتِ وَأَنْزَلْنَا مَعَهُمُ الْكِتَابَ وَالْمِيزَانَ لِيَقُومَ النَّاسُ بِالْقِسْطِ ۖ وَأَنْزَلْنَا الْحَدِيدَ فِيهِ بَأْسٌ شَدِيدٌ وَمَنَافِعُ لِلنَّاسِ وَلِيَعْلَمَ اللَّهُ مَنْ يَنْصُرُهُ وَرُسُلَهُ بِالْغَيْبِ إِنَّ اللَّهَ قَوِيٌّ عَزِيزٌ

“We have already sent Our messengers with clear evidences and sent down with them the Scripture and the balance that the people may maintain [their affairs] in justice. And We sent down iron, wherein is great military might and benefits for the people, and so that Allāh may make evident those who support Him and His messengers unseen. Indeed, Allāh is Powerful and Exalted in Might.” (Surah al-Hadid, 25).

In the design, Nadimi focused on these three pillars of Islamic government: scripture, balance/justice and iron/strength/endurance. He mailed his sketches to the office of Ayatollah Khomeini, and a few days later he received a call from Ayatollah Hashemi Rafsanjani to confirm that Ayatollah Khomeini and his companions had agreed upon his design to be the official emblem of the national flag of Iran. The emblem was approved on June 9, 1980.

Unlike 21 Muslim majority-countries that depict the crescent on their flag, Iran’s flag does not. Nadimi mentioned that this might be due to the fact that Ayatollah Khomeini wanted to stress towhid – unity – and thus wanted that emblem to reference only God, not any particular visual symbol.

But the Allah emblem still contains crescents inside it: the shape of the crescents is meant to resemble the phrase lā ilāha illā allāh “There is no god but God”. Nadimi emphasizes the middle and center letter (ا) of the Allah sign on the flag and emblem. This rod shape is inspired by the pillar of balance and also the iron (hadid) in the sura al-hadid. There is also a tashdid, a marker used in Arabic and Persian to double a letter’s sound. In this context, it means to double the strength of the shaft depicted through the main letter. The sword is the strength of sovereignty of state but the pillar is supposed to symbolize the balance and justice of the state.

At the top and bottom of the green and red bands of the flag is Allāhu Akbar written out in Kufic maʿqelī script 22 times. 22 is significant because the Revolution’s victory happened on the 22 day of the 11th month of the Iranian calendar. In my meeting with Nadimi, he mentioned that in the original sketch of Kufic design, they encountered a funny hiccup. The way “Allāhu Akbar” was written out, it ended up looking like “USA” written out in lowercase. Given that Iran’s Revolution had just deposed a US-backed dictator and the United States was turning out to be the new Islamic Republic’s biggest foe, the design was deemed inappropriate and Allāhu Akbar had to be sketched out in Kufic script differently.

A flag for Imam Zaman

The characteristics of the Iranian emblem are not well known partially because Nadimi is not a fan of speaking about is work. He told me this was because designing the flag “was a more divine and spiritual act for me. Due to its grandness, I am speechless when I try to describe it.” When I asked him his opinion about the endurance of the flag decades after the Revolution and if he ever expected his emblem to last this long, he looked at me with confidence and said: “We designed this flag in order to hand it over to the hands of Imam Zaman, inshāllāh,” referencing the religious leader that devout Shi’a Muslims believe will return in the End of Times to usher in an era of peace and justice.

Only months after the emblem’s approval, Iraq invaded Iran, beginning an eight year war that left a million dead. Nadimi’s flag came to decorate the coffins of Iranian soldiers killed on the battlefield. As a result, this new flag came to carry heavy emotional weight for Iranians almost immediately. As part of the generation that came of age during the war, the flag triggers a mix of pride, endurance and intense nationalism in me. Seeing the flag on Tehran’s hills today is a reminder of that time for those of us who lived through war and its aftermath.

However, the flag of Iran after the revolution was intended to represent the most fundamental values of Islamic government. As the most important part of the emblem, the iron pillar symbolises justice. In the years after the creation of this flag, the public has interpreted the emblem in many various ways. While the flag was designed in aftermath of the revolution as a powerful tool to carry on its legacy, in the 1980s Iran-Iraq War, it became an emotive symbol for the whole nation. Decades after, there are still debates regarding the flag and if it symbolises the Islamic government outlined in surah al-Hadid. But at the end of the day, what Nadimi wanted to portray or hoped for becomes irrelevant, since the emblem and the flag’s meaning for the Iranian public emerge from the social life of the flag.