Timur Khan is a Dutch-Pakistani master’s student of Middle East Studies at Leiden University, Holland. His work focuses on the history of Afghanistan and North-West Pakistan in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Peshawar, the urban heart of Pashtun culture in the north-west of modern Pakistan, witnessed significant upheaval during the 19th century. Since the late 18th century the Afghan Durranis, based in Kabul to the west, had maintained Peshawar as a winter capital. In 1823 the city was seized by Ranjit Singh, the ruler of a Sikh kingdom centered on Lahore to the east. In 1849, the British East India Company took the city from the Sikhs as they conquered the Subcontinent from their base in Calcutta. A final change of hands took place in 1858 when direct British governance came into effect, making faraway London the ultimate power over Peshawar. In these turbulent times the city was a frequent target of violence on the part of the conquerors. It was also a locus of profound cultural and social change wrought by encounters with imperial states.

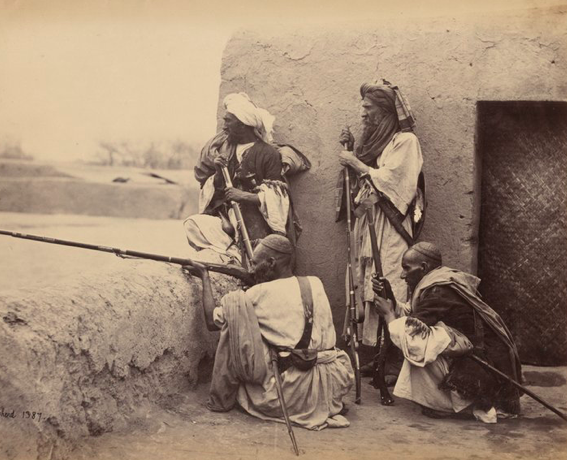

Pashtuns, Peshawar’s dominant ethnicity, have historically been defined by certain recurring, narrow categories of identity. Colonial writing favors the image of the Pashtun as fiercely tribal and fanatically Muslim in identity. Pashtun nationalism places ethnicity as the chief marker of belonging, while Pakistani nationalism downplays ethnicity and sees Pashtuns as part of a common Muslim community in South Asia.

Modern scholarship has certainly produced works which challenge any unitary perspective on Pashtun identity (e.g. Banerjee, The Pathan Unarmed), but tends to favor kinship lineage groups, religion and ethnicity as primary elements (e.g. Ahmed, Pukhtun Economy and Society; Nichols, Settling the Frontier).

These understandings of Pashtuns suffer when applied to the 19th century. Pashtun political identity was a tapestry of overlapping, even conflicting elements encompassing the family, state, language, region and faith, changing over time and with political shifts. Peshawar’s unstable political situation until 1858, and the tensions of British rule thereafter, compounded the diffuse and shifting nature of political identity. This contingency is worth exploring because it challenges the assumed primordiality and coherence of identity both when looking back on history and looking to our own societies; it demands acknowledgement of how, even in a few decades, circumstances can break down and reorder established notions of selfhood.

Grounding one’s perspective in the affairs of one individual helps us understand how competing elements of self coexisted in 19th century Peshawar. Afridi Khan, a malik (landlord) of the Khalil tribe of Pashtuns, is a worthy candidate who lived astride boundaries of tribe, state allegiance, even faith. He is also my own thrice great grandfather. At the time of his birth as Bashir Khan around 1839, repression by the Sikh state had driven his family temporarily out of their village of Mulazai, near Peshawar. They fled some hundred kilometers west to the Tirah valley, near the Khyber Pass. There he grew up among the Afridis, a separate tribal confederation of Pashtuns. He was an illiterate, conservative man and a Muslim. He was also a staunch British ally, serving in the colonial military, often against his Muslim coreligionists, from 1857 until his death in 1903. In another apparent contradiction, despite being a British subject he likely maintained a government pension from the amir of Kabul, a foreign sovereign, until 1878. Afridi Khan’s life as part of the social elite of 19th century Peshawar indicates that lineage, faith, tribe and ethnicity were not stable and dominating aspects of identity; rather they were competing and often changing over time.

Between Three Empires & Two Tribes

Bashir Khan’s father, Amir Khan, was a man of varying political loyalties. In 1834 he made a name for himself working with the Sikh authorities by helping suppress a mutinous army regiment; he was made an infantry commander and granted jagirs (land grants) for two villages, enhancing his means as a landlord. Nevertheless, in what appeared to be a common cycle of cooperation and resistance among the maliks of the Khalil tribe, Amir Khan later fled his rulers and took refuge in the remote Tirah valley. The precise circumstances are unclear, but family lore has Amir Khan and other landlords of the region make a dramatic escape from Peshawar’s Bala Hissar fortress at night, having been locked in and threatened with execution by the Sikhs for refusing to go to war on their behalf. It is likely that this war was against the Amir of Kabul, Dost Muhammad, who attempted to retake Peshawar in 1835.

Faced with the prospect of fighting an Afghan Muslim ruler, and already chafing under heavy taxes and military repression, most of the Khalil landlords fled their lands and swore allegiance to Dost Muhammad. The Amir ultimately failed to take Peshawar, and from 1837 many of the Khalil were reconciled by the Sikhs and had their jagirs reinstated. Amir Khan probably returned around 1843, during a later round of amnesties. Ultimately he would side with the British during the Anglo-Sikh Wars of 1845-6 and 1848-9, again abandoning his sovereign in Lahore. Thus, while Amir Khan acted partially along tribal and religious lines in 1835, he was aware that the political life of the era followed its own logic, and that the status, and even survival, of his family required pragmatic action and frequent reconsideration of those parts of his identity.

Bashir Khan was most likely born during the family’s exodus in Tirah. The Khalil have historically close relations with the Afridis of Tirah despite belonging to different Pashtun tribal confederations, each defined by claims to a shared ancestry reaching into antiquity. However Bashir’s connection was especially strong. He grew up among them, and despite his youth upon returning to Peshawar, the region had a profound influence on him. In the family it is remembered that he spoke Pashto with a distinct Tirah accent throughout his life. As an adult he changed his name, legally, to Afridi. To associate himself so personally with a tribe to which he did not belong by descent was a powerful assertion of difference, and an indication that a tribal understanding of the self was not absolute.

Afridi Khan’s story challenges the idea of the kinship lineage group as a primary facet of identity among Pashtuns. One oral account links Afridi’s name change to his murder of his half-brother over an inheritance dispute in 1869. Citations from British officers remark on Afridi’s poor relations with his family and community, likely owing to this crime, despite unchallenged primacy among his siblings. It is possible that both his name change and enthusiastic military service in the Khyber were ways of escaping the social pressures of his village and being near the Afridis, with whom he felt more at ease. Inter-family violence was and is not uncommon in Pashtun communities, but to distance oneself from one’s lineage group and forge parallel military and tribal identities shows Afridi’s willingness and ability to reject typical categories of belonging.

Relations between Pashtun maliks and British authorities create further complications in any understanding of Afridi Khan and his contemporaries as belonging firmly to religious, tribal or familial categories of identity. Amir Khan’s experiences with the Sikhs demonstrated the malleable nature of regional elites’ attitudes to ruling states, be they Muslim or non-Muslim. Despite allying with the East India Company during the wars which led to its conquest of Peshawar in 1849, this malleability again came to the fore in 1851-52. British efforts to affect more direct administrative control in the region led to a land settlement scheme in Khalil tribal lands which deprived maliks of tax harvesting rights. When they resisted, the landlords were duly carted off to Lahore for imprisonment. Amir Khan was likely among them.

A Respected Muslim, a Colonial Officer

The Khalil land crisis soon ended in compromise and the maliks were released. In May 1857 Amir Khan was given another chance to display his political flexibility, along with his son Afridi. In that year, large portions of the East India Company’s army mutinied, and British rule in the subcontinent was seriously challenged. While many of the rebels were Muslim and framed the war as a battle for the future of Islam in India, this did not much concern Amir Khan’s family. Afridi was apparently the first in the district to offer his retainers to the British, and he and his brothers marched with Company forces on rebel-held Delhi. When Yusufzai Pashtuns began their own local revolt, he fought them as well.

The many Muslim mutineers’ self-consciously religious motives did nothing to stop him and his brothers from marching with vigor to Delhi. Troops from the North-West traveled, one sweltering Ramadan, from Mardan to Delhi in twenty-seven days in a famous rapid advance. Afridi may, like many of the Muslim elites of North India, have seen the mutiny as a disloyal act by low-class ruffians against a legitimate government and resented the strife (fitna) wrought by rebellion. Alternatively, he simply felt he was on the winning side. In any case, neither a common religious identity with the Indian rebels nor ethnic and religious ties to the Yusufzai was sufficient to stop Afridi from fighting for the British.

Afridi would go on to be a dependable servant of the Government of India, but his relationship with the state was not static, as an episode in the buildup to the Second Anglo-Afghan War in 1878 reveals. Reception of a Russian embassy to Kabul in July by the Amir of Afghanistan, Sher Ali Khan, led the British to demand their own embassy be welcomed. In September a mission under Sir Louis Cavagnari was assembled, of which Afridi Khan was a part, to open the way into Afghanistan for the ambassadorial troupe.

Sher Ali’s commander at Ali Masjid in the Khyber Pass attempted to forestall the British by sending missives to the landlords of Peshawar warning that their allowances from the Amir would be severed should they go with Cavagnari. While the maliks disregarded the Amir’s wishes this detail suggests that from 1849 to 1878 Afridi Khan, while a British subject, was technically also a pensionary of the Amir, a position that implies a ‘feudal’ bond like that shared between the Afghan Amirs and those frontier tribes never formally brought under British rule. While this bond evidently had little practical power by 1878, it indicates that Afridi’s allegiances to Kabul formed part of his political identity not immediately contradicted by his loyalty to the British.

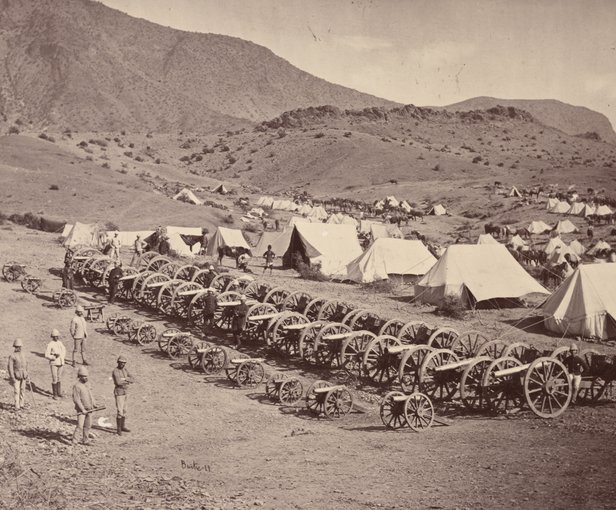

Cavagnari’s mission were prevented from entering Afghanistan, giving the British a casus belli and an opportunity to place a more pliant, anti-Russian Amir on the throne. As war broke out in November 1878, it became clear that Islam would continue to play a subordinate role in Afridi’s political choices – though it is unlikely he ever claimed to be anything less than a faithful Muslim. As in 1857, Afridi was “conspicuous” in his zeal as one of the first khans to come forward for service. He maintained a retinue of twenty-nine cavalrymen “at considerable monthly loss”, raised levies in the Khyber and remained stationed there for two years, the majority of the war. Soon after the outbreak he led irregulars during an attack on Ali Masjid.

Afridi continued to defy the supposed primacy of Islam, ethnicity and tribe in the political identity of Pashtuns during the final major campaign of his life. British attempts at imposing greater control over the Khyber districts provoked uprisings in Tirah in 1897. Afridi once again proved his commitment to state service. He “held lower Kurrum together practically unaided” against fighters of the Afridi and Orakzai tribes, including troops formerly under his own command. At one point the elders of those tribes wrote to him, imploring him to make them a favorable peace with the British. “All Islam respects you,” they wrote, “you are a Musalman and respected.” Neither flattery nor religion induced Afridi to disobey his rulers. He died on November 21st, 1903, remembered as “a gentleman”, “a stout Yeoman (landowner, officer),” “a friend,” and a “fine plucky old man” by his officers.

Afridi’s experiences demonstrate that an attempt to understand Pashtuns, particularly 19th century Pashtun elites, according to stable categories of religion, ethnicity, tribe, political allegiance or kinship group will fall short. All these elements could change meaning, coexist and conflict with each other to varying degrees over time, and many of the people who inhabited them were aware of this complexity. While the exhortation of the Khyber elders to Afridi Khan reminding him that was “a Musalman” at first seems to frame the self solely in the kinship of Islam, it was in fact a demonstration of their understanding that different facets of identity could be balanced against each other. Rather than demand he take up arms, the elders acknowledged and sought to use his place as both a colonial officer and a Muslim.

Neither tribal, religious nor kinship identities are sufficient to understand or compel Afridi Khan. The historical record shows they were never fixed nor absolute. Tribe, family, ethnicity and faith were not all-powerful motivators, nor did they totally define the self. Afridi Khan was at once an Afridi, a Khalil, a Muslim, a Pashtun, a patriarch, a British subject and a military man. Each of these identities was continuously undergoing change and being reconfigured in relation to another.

Bibliography

(1888) Journal Asiatique, Huitième Série, Tome XII. Paris, Société Asiatique.

(1898) Military Operations on the North-West Frontiers of India Vol. I: Papers Regarding British Relations with the Neighbouring Tribes on the North-West Frontier, and the Military Operations Undertaken Against Them During the Year 1897-98. London, Darling & Son, Ltd.

Adamec, L.W. (2006) Historical Dictionary of Afghanistan. New Delhi, Manas Publications/Scarecrow Press, Inc.

Banerjee, M. (2001) The Pathan Unarmed. Islamabad, Oxford University Press.

Barfield, T. (2010) Afghanistan: a Cultural and Political History. Princeton, N.J. Princeton University Press

Caroe, O. (1983/1958) The Pathans. Karachi, Oxford University Press.

Das, G. (1878) Tarikh-i Peshawar. Lahore, Koh-e-Noor Press.

Dey, K.D. (1881) The Life and Career of Major Sir Louis Cavagnari, CSI, KCB, British Envoy at Cabul, Together with a Brief Outline of the Second Afghan War. Calcutta, J.N. Ghose & Co, Presidency Press.

Government of the Punjab (1898) Gazetteer of the Peshawar District 1897-8. Lahore.

Massy, F. (1890) Chiefs and Families of Note in the Delhi, Jalandhar, Peshawar and Derajat Divisions of the Panjab. Allahabad, Pioneer Press.

Nichols, R. (2017/2001) Settling the Frontier: Land, Law and Society in the Peshawar Valley, 1500-1900. Islamabad, Oxford University Press.

Rashid, H. (2005) History of the Pathans – Vol. II: The Sarabani Pathans. Islamabad, Self Published.

2 comments

Very good article. Thanks for writing it.