Samuel Tafreshi is an Iranian-American writer based in Beirut, Lebanon. He holds a BA in Religion and his work has focused on comparative analysis of Persian and Western literature.

***

Reading Hamlet in Persian or seeing the play on the Iranian stage, one is struck by how little the characters resemble the 16th century Englishmen most audiences are familiar with. Hamlet and Ophelia might be called Siyavash and Mahtab, while Denmark might resemble Tehran. Over the last 129 years in Iran, Shakespeare and his characters have undergone a startling transformation in the process of translation and adaptation, one affected at each step by the movements of Iranian politics and the identities of the translators.

Shakespeare’s plays have attracted the attention of each passing generation of Iranian translators and directors. Over time, adaptations have taken on a variety of forms with some sticking closely to the source material while many others chose to depart from the original in names, setting and even plot structure. Translators have altered the language according to censorship restrictions, Persianized the content to make it more relatable to an Iranian audience, and created alternative endings to Shakespeare’s plays.

Shakespeare’s works have cultivated such a variety of interpretations partially because his works were not introduced in a single, authoritative form. When the plays reached Iran they were written in Arabic and French as well as English. If one wanted to read a Shakespeare play in 19th century Iran, Arabic or French was much more accessible than English. Prior to the existence of any Persian translation of Shakespeare, Azerbaijani and Armenian-language productions took place in Tabriz. Iranian tourists saw Shakespeare performed on Russian stages and wrote about productions in their travelogues and diaries. As a result of this multitude of influences, the English text didn’t possess an authority Iranian translators and directors were beholden to. Instead, Persian renditions of Shakespeare reflected translators’ relative freedom of interpretation and demonstrated the plays’ flexibility, allowing Hamlet to become Siyavash and many other unexpected transformations to occur.

The Beginning of Shakespeare and the End of the Qajars

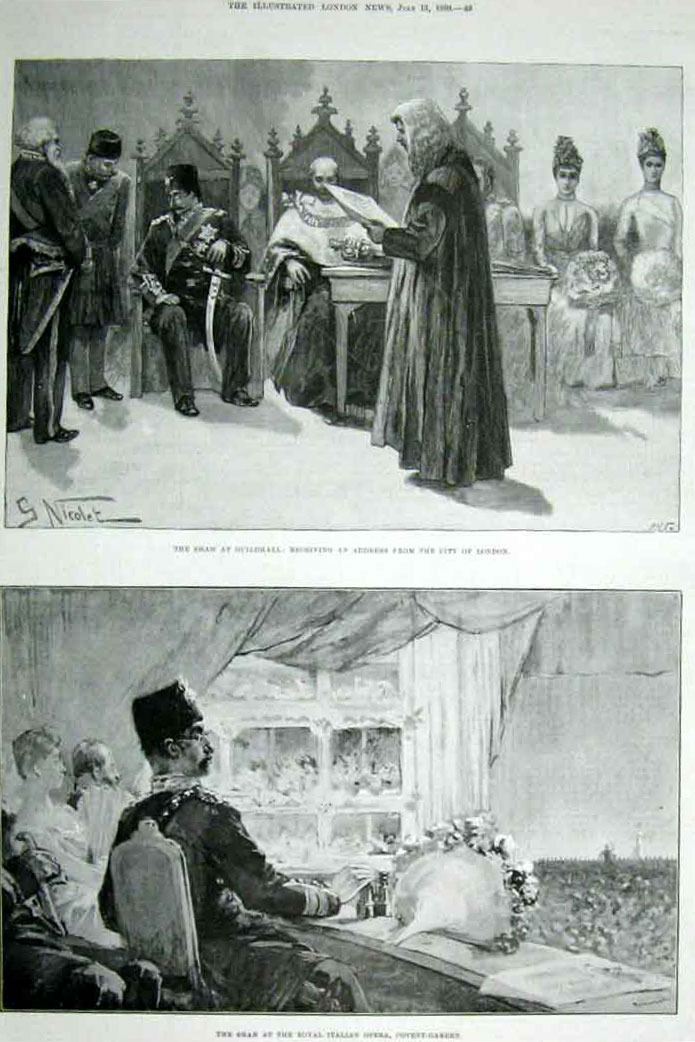

The first Persian translations of Shakespeare took place as Western-style theatre was being introduced to Iran by Nasir al-Din Shah Qajar. Nasir al-Din Shah visited Europe on diplomatic trips in 1873, 1878, and 1889. He recorded in his 1873 diary that he was especially impressed by the operas, circuses, and theatres he attended. In 1882, Nasir al-Din Shah established a theatre hall at Dar al-Fonun University and in 1885 ordered the creation of a translation bureau at the royal court in hopes of bringing to Iran the theatre he’d enjoyed in Europe. Nasir al-Din Shah considered adapting local theatre for the Western stage, but at the time many felt that traditional Iranian theatre couldn’t easily be adapted to this format.

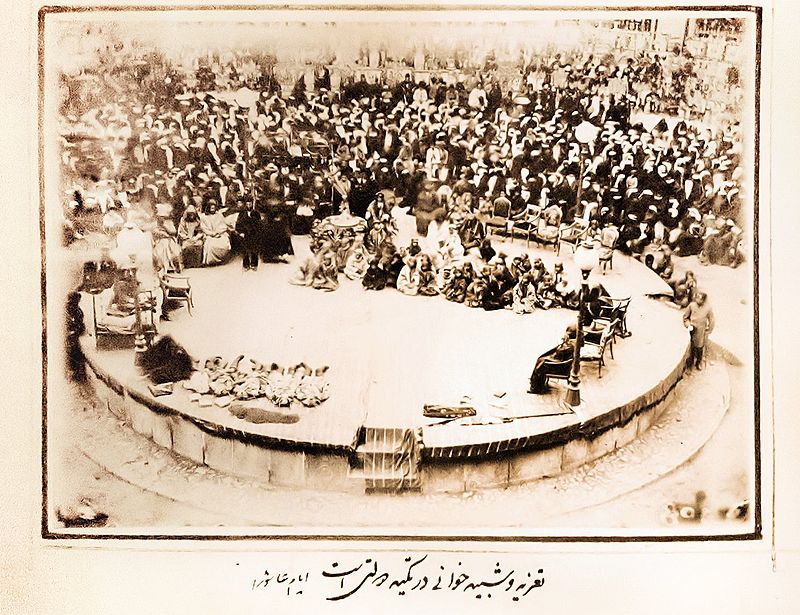

Traditional Iranian theatre such as Naqqali (story-telling) and Ta’zieh (religious passion plays) did not easily fit Western-style theatre. Naqqali usually involves only one performer and was most often set in coffeehouses, while Ta’zieh performances traditionally revolved around mourning in the month of Muharram and its stages were constructed only for the month. The intimacy fostered by the coffeeshop or household setting is integral to the effect of story-telling in a Naqqali performance. Ta’zieh, on the other hand, often depict the martyrdom of Imam Hussein at Karbala and rely on the audience’s participation in the mourning. In both of these styles of theatre, the relationship between the performers and the audience was crucial and presented problems for adapting these genres for the more distant relationship of the audience to the Western stage. As a result, the translation bureau of the court was established in 1885 and began the first major initiative to translate European plays into Persian.

Most early Shakespeare translators were Qajar or Pahlavi statesmen who had been among the first waves of Iranian students sent by the court to study in Europe during the 19th century. Some were translators or scholars by profession, others worked within Iranian embassies in Europe, and a few held major positions within the Iranian government. Hosseinqoli Mirza Saloor, the eldest son of the ruler of Hamadan and eventual ruler himself, was the first to translate Shakespeare into Persian in 1900 in his translation of The Taming of the Shrew (Majliseh Tamashakhan: Be Tarbiat Avardaneh Dokhtareh Tondkhuy). As a Qajar educated in France, Saloor translated from French rather than the original English. Shakespeare would not be translated from English until 1914 when Mirza Abolqasem Khan Qaragozlu, or Nasir al-Mulk, began his translation of Othello.

Nasir al-Mulk, the first Iranian student at Oxford in 1879, was the first to translate Othello and The Merchant of Venice into Persian. Nasir al-Mulk served as Minister of Finance several times, Prime Minister in 1907, and most notably was the Regent for 14-year-old Ahmad Shah Qajar in 1910 following Mohammad Ali Shah’s forced abdication. It was only in Nasir al-Mulk’s retirement, when Ahmad Shah Qajar came of age and was able to rule, that he turned to Shakespeare translation. While Nasir al-Mulk’s role in government was by far the greatest of the early Shakespeare translators, the group is defined by politicians and diplomats who witnessed or participated in the 1905-11 Constitutional Revolution that overthrew the Qajar monarch.

During this period, Iranian intellectuals developed a greater interest in Shakespeare’s plays and poetry. Several literary publications emerged focusing on Western cultural works — such as Majalle Adabi, Ra’d, and Bahar — and began publishing critical essays on Shakespeare. In 1909, parliamentary member and founder of Bahar, Yusuf Etesami, published an essay that included a brief history of drama, a biography of Shakespeare, and Persian translations of excerpts from A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Macbeth translated from Arabic and French. Through these publications, Shakespeare’s popularity grew to the point that the newspaper Ra’d even published the news of Shakespeare’s birthday being celebrated in Stratford, England. Iranian intellectuals’ increasing interest in Shakespeare during the Constitutional Revolution reflects some of the secularising trends in the arts popular among constitutionalists looking toward European cultural and political models.

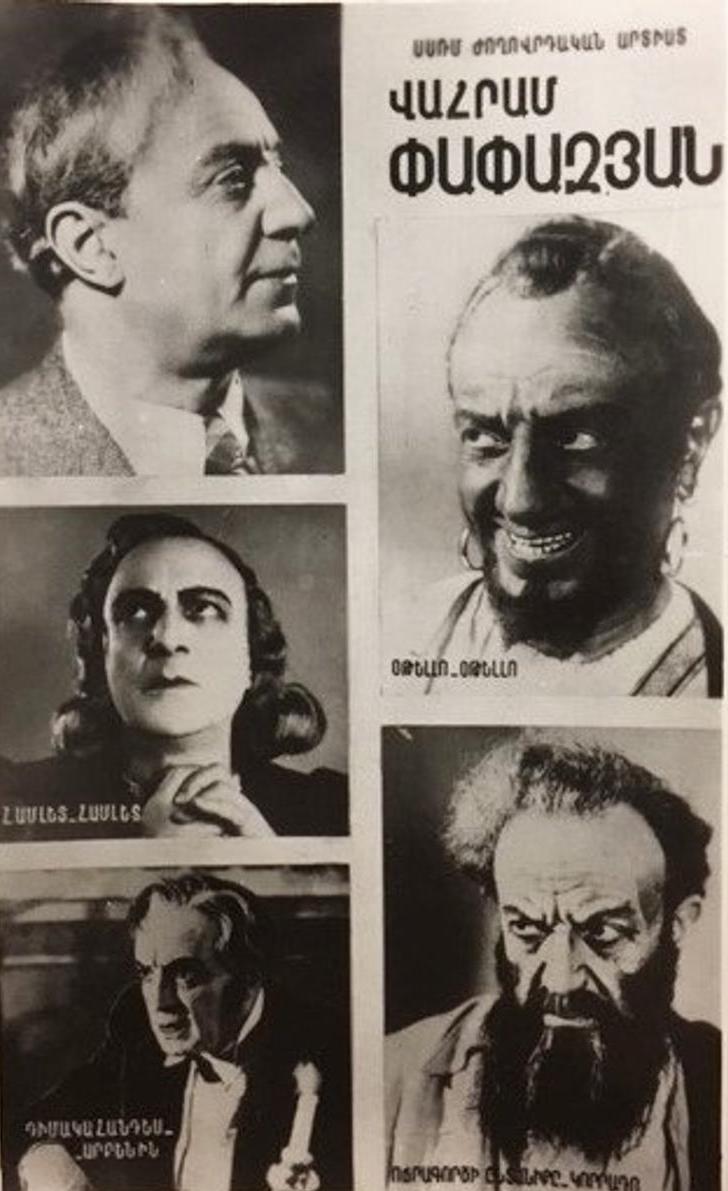

The ascension of the Pahlavi dynasty brought even larger support for Shakespeare’s work and the production of European plays in general. But it also brought new trends in censorship. Reza Shah Pahlavi financed the arts more than any of his predecessors as part of his attempt to modernise Iran’s cultural institutions. In 1933, Reza Shah established the National State Theatre Company and invited the renowned Armenian actor Vahram Papazian to perform Hamlet and Othello. Papazian did not speak Persian but he did speak Armenian, Russian and French. As a result, while his accompanying actors performed in Persian, he performed in French. Despite the bizarre appearance of one actor speaking in French while all others were speaking Persian, this conveys how familiar some of the audience would have been with French at this time. While English gained prominence among the educated elite under Reza Shah, French had long been the primary European language taught in Iran and at one point there was even a bilingual newspaper in Tehran, Vatan/La Patrie.

Papazian’s performance of Hamlet would become infamous as the only performance of the play for decades. Hamlet — a tragic tale of revenge revolving around Prince Hamlet of Denmark’s attempts to avenge his murdered father against his uncle and mother who killed him and usurped his throne — proved too inflammatory for Reza Shah. The Pahlavi regime hoped audiences would relate Hamlet to the corrupt Qajar regime and engender more support for their government. But Reza Shah was displeased following the performance. He subsequently banned any play featuring murdered kings, mad princes, unfaithful queens, and usurped thrones from the National Theatre. Other than this single performance by Papazian, Hamlet would not grace another Iranian stage while a Pahlavi sat on the throne.

Becoming Prince Siyavash of Tehran

A number of early trends in the translation of Shakespeare’s works would evolve to mark Persian translations of Shakespeare as a distinct category. One trend present since the first Shakespeare translation by Hosseinqoli Saloor in 1900 is that Iranians often translated Shakespeare into Persian from another translation rather than from English. Saloor used a French translation of The Taming of the Shrew to render the play in Persian. Writer and prominent Tudeh Party member, Mahmood Etemadzadeh, similarly chose to translate Hamlet from French rather than English in 1990. Despite being fluent in English, Masood Farzad, poet and translator for the Iranian Embassy in London, also consulted Arabic translations of Hamlet as he composed his Persian translation in 1940. The trend reflects the myriad of cultural encounters that brought Shakespeare to the Persian-speaking audience. This tendency suggests that Iranian translators did not consider English inherently more authoritative than another language’s interpretation. Instead they freely adopted Shakespeare as his work was understood elsewhere.

As translators explored various ways to render Shakespeare for the Persian-speaking audience, they engaged in a process of cultural adaptation to meet the needs of their audience and their time. When writer and translator Mostafa Rahimi translated Hamlet in 1992, he struggled with how to express the language of the play accurately and within the restrictions of the Islamic Republic. In order to ensure his work would be staged, Rahimi sanitised the language of the play. Mentions of wine became sharbat (a traditional sweet drink) and eshq (love) was replaced with jashn (bliss). Through Rahimi, the Hamlet of post-revolutionary Iran became a tale of resistance against the tyranny of kings, stressing the hypocrisy and corruption of the royal court.

Many also struggled with translating the abundant and specific metaphors found in plays such as Hamlet and looked to classical Persian literature to match the complexity of Shakespeare’s language while reproducing the spirit of the text for Iranian readers. In Abbas Horri’s 2003 translation of the line from Hamlet, “as this temple waxes, / The inward service of the mind and soul / Grows wide withal,” he translates “mind and soul” as “jaan o kherad” (literally meaning soul and sense) to mimic the opening line of the Shahnameh: be naam-e khodaavand-e jaan o kherad (in the name of God, God of soul and sense). The Shahnameh provided abundant inspiration for translators seeking to equal the lofty language of Renaissance-era texts.

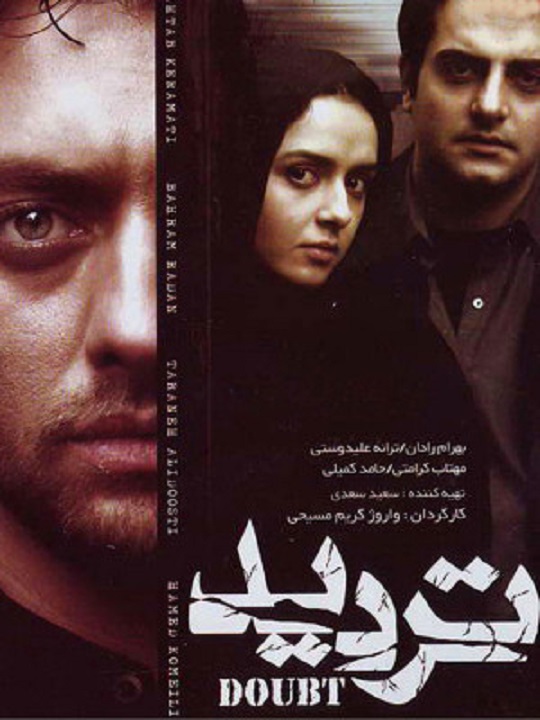

The plays sometimes took on an explicitly hybridized form in which translators sought to make the plays more relatable by changing the setting and character names from their European context to an Iranian or occasionally Turkish one. In Aziz al-Allah Saman’s 1938 Persian translation of Romeo and Juliet entitled Leila va Majnooneh Gharb (Western Leila and Majnun), Romeo and Juliet were recast as the forbidden lovers of Nizami Ganjavi’s twelfth century poem of the same name. Although this style of adaptation has been present since the first few decades of Shakespeare translation, contemporary adaptations transform characters, setting and plot even more freely. In Varuzh Karim-Masihi’s 2009 film adaptation of Hamlet, Tardid (Doubt), Hamlet becomes Siyavash, the son of a wealthy family in Tehran, his best friend Horatio becomes Garu and his paramour Ophelia is Mahtab. Karim-Masihi’s Tardid goes so far as to change the ending of the play itself. Hamlet ends with all of the major characters dead whereas Tardid concludes with Ophelia/Mahtab alive.

In some cases Iranian directors have not just played with the characters to tell different stories; they have even directly integrated Iranian rituals and beliefs into the play, producing versions of Shakespeare that deal with specifically Iranian issues. In Ebrahim Poshtkuhi’s 2010 play Hey! Macbeth, Only the First Dog Knows Why It Is Barking!, the production integrates the plot of Macbeth into the workings of the Zar ceremony — a southern Iranian ritual meant to help those afflicted with bad winds that attach to a person bringing them depression and disease. Zar rituals are becoming less commonly practiced in modern Iran as more people choose to seek out modern medicine to remedy their ills, but Postkuhi’s adaptation aims equally to adapt Macbeth and to preserve Zar rites.

Ibrahim Poshtkuhi’s Hey! Macbeth, Only the First Dog Knows Why It Is Barking! Performed by the Titowak Theater Group

Toward a Multicultural Shakespeare

Each of these productions adapts Shakespeare to deal with specifically Iranian issues while maintaining the original in some way, shape, or form. Whether depicting Zar rites through the story of Macbeth or staging Hamlet within the confines of Islamic Republic censorship, it is clear that Shakespeare’s plays have been malleable for Iranians. One could argue the plays were flexible because their arrival was so heterogeneous. Considering how often translators worked from Arabic or French translations and that Armenian and Azerbaijani productions pre-date Persian performances in Iran, it could be argued that the Shakespeare Iranians encountered was a cultural product of Armenians, Azerbaijanis, Arabs, and the French as much as that of the English. There is no way to isolate Persian translations of Shakespeare from the surrounding languages and cultures that introduced his work to Iran – nor have Iranians working with Shakespeare seemed interested in doing so.

Immediately discernible in the history of Shakespeare translation in Iran, moreover, is that the plays have been affected by the same political developments as the translators and directors. They have fallen prey to the same changing trends in censorship that the Iranian people have navigated over the last century. The beginning of Shakespeare translation came in the context of Nasir al-Din Shah Qajar’s efforts to modernize and bring European art and institutions to Iran. What was subversive under the Pahlavis proved, in some ways, palatable to the Islamic Republic. Hamlet has spoken French to Reza Shah, traded wine for sharbat in the 1990s, and gone by the name Siyavash in the 2000s. In many ways, it seems inevitable that as the plays were moulded by Iranians they would come to resemble the conditions in which they wrote more so than those of Shakespeare.

References:

Anushiravani and Jalayer. “Transcultural Hamlet: Representations of Ophelia and Gertrud in 21st-century Iran,” k@ta 19, Issue 2 (2017): 55-62.

Alexander, Edward. “Shakespeare’s Plays in Armenia.” Shakespeare Quarterly 9, no. 3 (1958): 387-94.

Beyad and Ali, ed. Culture-blind Shakespeare: Multiculturalism and Diversity. Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2016.

Ghandeharion, Jaghragh, and Sabbgh. “When Shakespeare Travels Along the Silk Road: Tardid, an Iranian Adaptation of Hamlet.” Acta Via Serica 2, no. 1 (2017): 65-84.

Horri, Abbas. The Influence of Translation on Shakespeare’s Reception in Iran: Three Farsi Hamlets and Suggestions for a Fourth. PhD diss. U of Middlesex, 2003.

Poori, Sepideh. “Iranian Theatre as Means of Intervention: The Intercultural Discourse in Hey! Macbeth, only the first dog knows why it is barking!.” Arab Stages 7 (2017): 1-12.

Rubin, Don, ed. The World Encyclopedia of Contemporary Theatre: Volume 5: Asia/Pacific. Routledge, Taylor & Francis, 2005.

Sanjabi, Maryam B. “Mardum-Guriz: An Early Persian Translation of Moliere’s Le Misanthrope.” International Journal of Middle East Studies 30, no. 2 (1998): 251-70.

Tardid/ [Doubt]. 2009. Dir. Varuzh Karim-Masihi. Perf. Bahram Radan and Taraneh Ali-Dusti. Farabi, DVD.

“Hey Macbeth, Only the First Dog Knows Why It Is Barking (Macbeth of Zar),” YouTube Video, 1:14:23, “Titowak Theatre Group,” May 7, 2014, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cAh380euK_c.

2 comments

This was a delightful essay on just how mediated translation always is.