The following is a guest post written by Leon Aslanov, an independent researcher working on Armenian-Azerbaijani relations as well as the languages, cultures and politics of the South Caucasus. He works as a Middle East Analyst at Integrity UK and is also affiliated with the London-based Programme of Armenian Studies.

A few years ago, pianos were placed around London for passersby to play and, on rare occasions, bring joy to the public. One day while walking through King’s Cross Station my ears heard a melody coming from one of these pianos. It sounded Armenian in musical texture, with a dash of jazz. Intrigued, I guessed which Armenian jazz musician it might be: Arno Babajanyan? Levon Malkhasyan?

I followed the sound and approached the musician: “Hello, are you playing Babajanyan?” – “No, who is that?” – “Aren’t you Armenian?” – “No, I’m Azerbaijani. I’m playing Vagif Mustafazade. The piece is “Baku nights” (Bakı gecələri)”. I was left perplexed- how could I have mistaken an Azerbaijani classic for an Armenian tune? I explained to him that I grew up listening to and learning to play the piano music of Arno Babajanyan, a relative of mine whose pieces were inspired by Armenian folk melodies, and that the music he was playing sounded similar.

He seemed to be just as gobsmacked as I was, and we proceeded to chat about these similarities. It was one of my first interactions with Azerbaijani music. But it began a long journey of recognizing how similar Armenian and Azerbaijani musical traditions really are. These similarities extend even to the instruments themselves, as the following video, focused on the shared kamancha heritage illustrates:

Despite living side by side for centuries, Armenians and Azerbaijanis often think of themselves as opposing groups. This can be seen clearly on Youtube, where music videos are littered with comments where people make national claims to songs that either sound similar or are exactly the same in both Armenian and Azerbaijani. Denying the clear signs of shared culture has become a means of defending one’s righteousness while preserving negative attitudes towards the “other”. This is especially true in the context of a territorial conflict like Nagorno-Karabakh where both sides deploy claims of historical ownership over cultural heritage to legitimize current political aims.

But although Armenian-Azerbaijani relations over the 20th century are often portrayed as a series of bouts of enmity and violence, Armenians and Azerbaijanis in the South Caucasus lived together for centuries in a relationship characterized primarily by mixing and co-existence. Living in the same towns, villages, and regions and sharing cultural traditions, they were far more similar than they were different. It was only the 19th and 20th centuries that saw the development of rigid national consciousnesses among Armenians and Azerbaijanis that imagined each as distinct peoples with separate, competing destinies. During the Soviet period, Soviet Armenia and Azerbaijan were demarcated as separate republics, each promoting the idea that they were culturally unique vis-a-vis the “other”. In the late 1980s and following the breakup of the Soviet Union, they became independent states- and then, amid the bloodshed of the Nagorno-Karabakh war, enemies.

But cultural expression reveals aspects of a people’s past that have an indelible effect on life in the present and imagination of the future. Long-lost lived memories are evoked through language, food, art and other forms of cultural expression that are a testament to how similar Armenians and Azerbaijanis really are. As my experience at the London piano shows, a long history of exchange and dialogue mean that Armenians and Azerbaijanis share more than they might like to imagine.

Music is a witness to this fact. It is an important carrier of cultural memory that can overcome the forced forgetting of the last century and remind us how closely bound these communities really are. Armenians and Azerbaijanis share not only instruments like duduk, zurna, and tar but even rhythms and melodies, like the classic Sari Aghjik/Sarı Gəlin. In this article, I explore Eastern Armenian and Azerbaijani folk music traditions that host a variety of shared songs, tales, and cultural features revealing just how intertwined these cultures are.

Sayat Nova

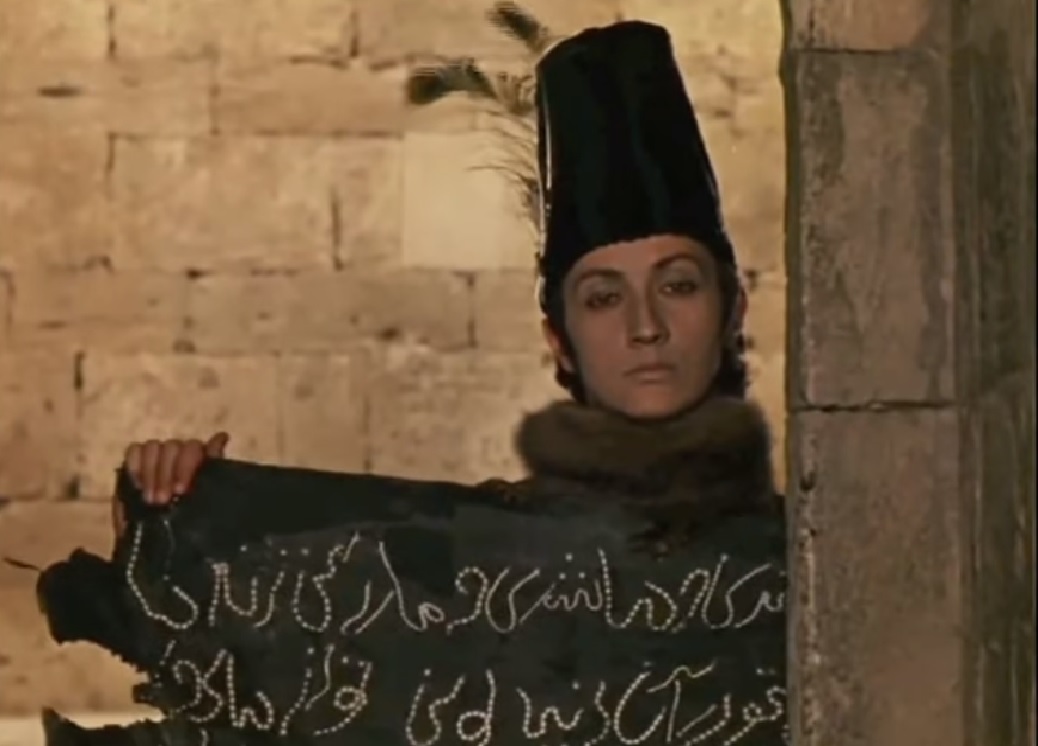

The most prominent example of shared musical heritage between peoples of the South Caucasus is that of Sayat Nova, an 18th century Armenian bard (known as ashough in Armenian and aşıq in Azerbaijani) who composed songs in Armenian, Azerbaijani, and Georgian.

His works in Azerbaijani are either unknown or hidden from the public. This is testament to the nationalisation of Sayat Nova, in which his legacy of multilingual artistic production has been written out and he is instead presented as a solely Armenian musician. His music and melodies were inspired by a range of folk musical traditions in the region. They were notated centuries after his death during an Armenian national musicological project- part of why he became to be seen as exclusively Armenian in the future.

Songs would be passed on from village to village, leaving behind little trace of where they came from or what the “original” version was. For instance, the Armenian song Mejlumi pes is said to have been composed by Sayat Nova; but there is an equivalent Azerbaijani folk song called Yar bizə qonaq gələcək with exactly the same melody.

The following source contains a number of Sayat Nova’s poems and songs in Azerbaijani written in Armenian script. Here is an excerpt from one:

Qulaq asın bəs bəndəyə, qazılar! (Listen to your slaves, oh judges!)

Çox ustadlar bizdən baş idi, gətdi, (Many of the masters have come and disappeared)

İnanmasın, dünya be-etibardır, (Do not believe in the lies of this world)

Çox aşıqlar əşq yoldaş idi, gətdi. (Many of the minstrels, companions of love, have gone away)

Shared songs and melodies

There are many examples of such songs whose melodies are identical, but are performed in differing musical styles and sung with different lyrics and titles. In certain cases, the composer of the song is known in one or both of the languages. However, this does not represent sufficient proof as to who actually composed the melody. A musician living in an ethnically-mixed town or village or a bard who travels from region to region may pick up melodies and transpose them with lyrics in their mother tongue.

For instance, the songs Alvan varder and Zov Gisher in Armenian are known to be composed by Gusan Sheram, a famous bard from Gyumri. Süsən Sünbül and Gözəlim Sənsən are the Azerbaijani equivalents of these songs. Although located in Armenia today, the region historically had a mixed Armenian and Azerbaijani population- so trying to figure out the “original” is probably impossible. But as the bard tradition has been transformed and institutionalized in each country, it is increasingly difficult to find folk bards who perform a multilingual repertoire. The memory of these bards is lost; but the songs live on as testament.

Indeed, there are several shared songs and dance melodies with no named author shared by both peoples. In some cases, they bear the same names, including: Sari Aghjik/Sarı Gəlin, Aman Tello, Shalaxo, and Enzeli. Sari Aghjik/Sarı Gəlin (“Golden Bride”) is a matter of particular controversial debate between Armenians and Azerbaijanis. Not only the melody but also the theme and lyrics are similar in both languages: a man is in love with a girl whom he cannot attain and so wishes for the death of her mother/grandmother. A famous rendition of this song was performed by Iranian musician Hossein Alizadeh and Armenian duduk player Djivan Gasparyan, and was sung in Persian, Azerbaijani and Armenian.

Wedding music played by Eastern Armenians and Azerbaijanis also have a common flavour. Dancing tunes are often based on a 6/8 beat: 6 beats with equal duration and stresses on the first and fourth beats, with a particular emphasis on the first. This beat is conducive to forms of shared dances that involve heavy usage of feet movements, such as Shalaxo. As these examples show, the similarities between Armenian and Azerbaijani music include instruments as well, including: dhol/nağara, dap/dəf, kamancha, tar, duduk/balaban, oud, kanon/qanun, shvi/tütək and zurna.

Rabiz

Another dimension of the history of musical interactions between Eastern Armenians and Azerbaijanis involves a form of music called rabiz. Rabiz is melancholic in both lyrics and melody, often employing harmonic minor scales. It was formerly accompanied by acoustic instruments, often a mellow-sounding duduk alongside the slow beat of the dhol. Nowadays it often employs a synthesiser and frequently has a faster pace. Several Armenian rabiz singers use lyrical motifs, melodies and singing techniques with roots in the muğam tradition.

Rabiz as a musical form hones a certain adaptability and flexibility that were developed by villagers and working-class people whose mind-sets have not historically been geared towards the paradigm of the nation-state and the idea that “this music belongs to us and that music belongs to you”.

Several Armenian songs in this genre have elements of code-switching from Armenian to Azerbaijani and incorporate a style of singing generally associated with Middle Eastern singing, involving the use of zəngulə [in Azerbaijani] or klklots [in Armenian], a type of undulation of the voice. The following video is an example of an Armenian singer code-switching. Rabiz singer Hayk Ghevondyan sings the lyrics getmə getmə gəl gözəl yar in Azerbaijani:

This can go both ways. Controversy once broke out when Rəmiş, an Azerbaijani singer from Ağdam, sang in Armenian at a wedding. The video is entitled, “Did Rəmiş sing in Armenian?”

The genre has changed over time. It currently includes a repertoire of songs that are of a patriotic nature that glorify the Armenian army, sanctify Armenian land and include anti-Turkish slurs. The irony of making use of shared cultural elements for nationalistic purposes is lost on audiences. To add to the irony, elements of middle- and upper-class Armenian society disparage this form of music and consider it to possess so-called “foreign elements” that have penetrated “true” Armenian music. This includes the use of klklots in Armenian singing, which has been equated by the aforementioned elements with muğam, although this is not the case since this voice quality also exists in other forms of Armenian music, including ashough and even religious hymns.

Furthermore, the use of duduk and zurna in Armenian music has an audial quality akin to the vocal zəngulə/klklots, which, in this case, is not objected to. Indeed, the duduk repertoire taught at the Conservatory in Yerevan teaches the scales inspired by the muğam tradition, itself based on a similar history as the Persian modal system known as dastgah. The rejection of rabiz, however, forms part of an effort to both distance Armenia away from “oriental” culture and push it towards “occidental” culture and to delineate a clear Armenian cultural identity separate from the Azerbaijani identity.

Remembering what was forgotten

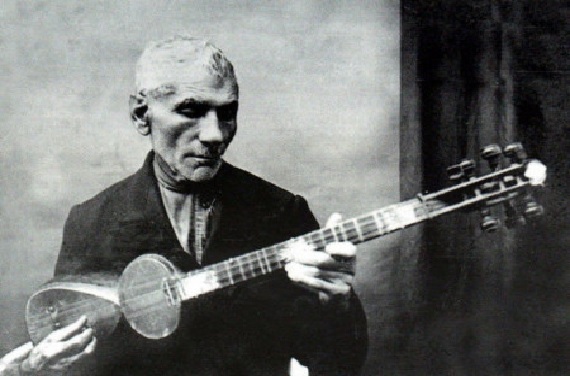

In some cases, musical traditions that have disappeared from one culture persist in the other. For instance, aşıq music wherein the aşıq stands tall with the saz and recites popular poetry, continues to be practised in Azerbaijan.

This tradition also existed among Armenians historically, however it waned into the abyss in the late 20th century. Another example is Meyxana (lit. wine house in Persian) a form of music particular to Azerbaijan in which men take turns to badmouth one another in an improvised manner under the backdrop of a slow repetitive beat and minor harmonic melody in a sort of “rap-battle”. Although the beat and melody also exist in Armenian rabiz music, the “rap-battle” set-up does not.

Despite the current animosity between Armenians and Azerbaijanis, as this article makes clear there is a long history of musical collaboration. The possibilities for collaborations are endless thanks to the centuries-old development of musical traditions in constant contact with eachother. The last known collaboration between folk singers from both countries took place in a concert in Baku in 1987, a year before the initial clashes over Nagorno-Karabakh erupted. But more recently, musical commonalities have also been used as part of reconciliation efforts as documented in the following short film about the kamancha, an instrument common to both cultures.

The imagined contours of national heritage when it comes to music are broken when the similarities revealed. Debates around origins of songs and instruments become redundant when removed from nationalistic discourse. At that point, this shared musical heritage becomes something that brings us together instead of dividing us.

References

Abrahamian, Levon & Pikichian, Hripsime. “The Path of R‘abiz,” pp. 97-108. Abrahamian, Levon. Armenian Identity in a Changing World. Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda Publishers, 2006.

Agha, Javid. For all that divides us, music brings us together. OC Media, 2019.

Leupold, David. The Echoes of the Disappeared: Rabiz Music as a Reverberation of Armenian-Azerbaijani Cohabitation. Journal of Conflict Transformation: Caucasus Edition, 2018.

Panossian, Razmik. The Armenians: From Kings and Priests to Merchants and Commissars. Columbia University Press, 2006.

Tonoyan, Artyon. “Armenia-Azerbaijan: Rethinking the Role of Religion in the Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict,” ch. 2, pp. 11-33. Migacheva, Katya & Frederick Bryan. Religion, Conflict, and Stability in the Former Soviet Union. RAND Corporation, 2018.

Uzer, Umut. An Intellectual History of Turkish Nationalism: Between Turkish Ethnicity and Islamic Identity. University of Utah Press, 2016.

1 comment