The following is a guest post by Gabriel Doyle, a French-Australian Phd Candidate in History at the Center for Turkish, Ottoman, Balkan and Central Asia Studies at the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales in Paris. His dissertation focuses on urban change in Late Ottoman Istanbul through the perspective of foreign charitable organizations.

All photos taken by author, unless otherwise noted.

***

Yeşilköy is a quiet suburb of Istanbul’s greater metropolis. Lying along the Marmara Sea, it offers cosy cafés, outdoor sport facilities with a sea view and stylish shops. The suburb today appeals to well-off inhabitants of Istanbul who work in the Turkish metropolis yet seek the tranquility of a seaside village.

But Yeşilköy’s tranquility belies important traces of Turkey’s imperial past. Exploring San Stefano as it was called during the Ottoman rule, reveals in particular places evoking the Empire’s turbulent ending decades. Finding out what materially remains of San Stefano may contribute to our understanding of the Ottoman experience of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

In various corners of today’s Yeşilköy lie traces of a semi-colonial European presence, embarrassing Ottoman military defeats and diminished or disappeared religious communities. Even some broken beer bottles in a wasteland recall the history of conflicting sovereignties that took place in the Ottoman Empire before its collapse. It is these everyday remnants that we may call scars of Empire.

Arriving in Yeşilköy by train gives a first sign of these material traces: the station was built by the Deutsche Bank as part of a railway project linking the Balkan provinces to the capital (1871-1891). It resembles other small train stations built in villages along the railway line.

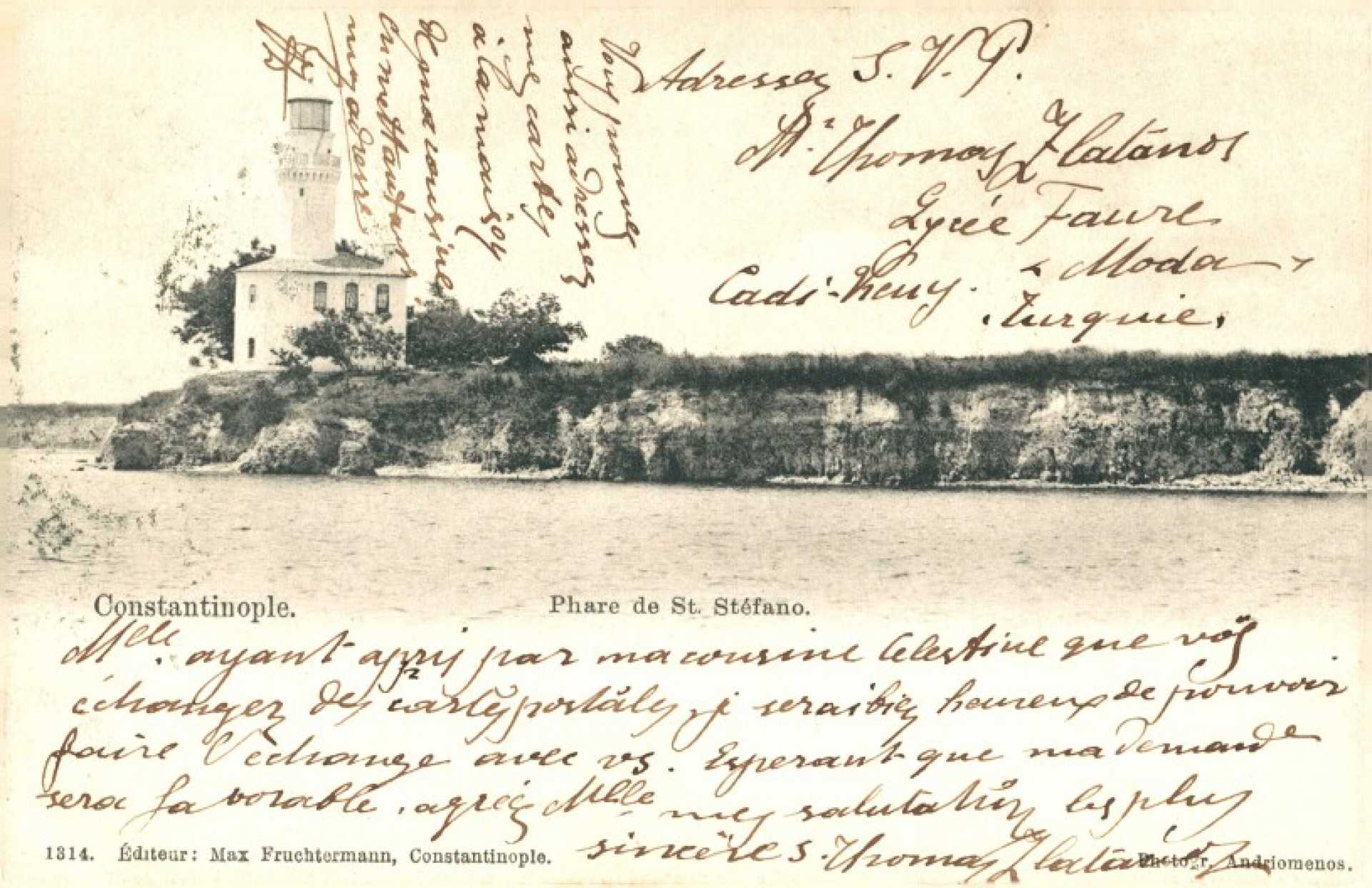

At the end of the beach, another monument recalls European engineer’s intervention: Yesilköy’s lighthouse, built in 1854 was the first main of its kind in the Ottoman realm. The lighthouse was built by French engineers, and was included in a network of lighthouses controlled by a concessionary company made of French capital: the Société Collas et Michel.

Even Yeşilköy’s natural environment recalls European imperial intervention in the Ottoman empire: the suburb was supposed to become a regional leisure centre with casinos, theaters, swimming areas and summer clubs. French writer Bertrand Bareilles mentions a major development plan for an Eastern Mediterranean Monaco that was prepared with investment from a German bank and the participation of French capital after the fall of Abdülhamid II in 1909.

Although this project failed, probably due to increasing Franco-German rivalry, the investors had still started buying property and planting trees. San Stefano was thus very much appreciated by wealthy families of Istanbul for summer retreats, similar to other sayfiye areas of Istanbul such as the Prince Islands. Yeşilköy’s streets line singular Swiss looking wooden chalets, all built during the last decades of the Ottoman empire.

Today, despite the massive infrastructure all around Yeşilköy, the surrounding woods make it an even more attractive spot in Istanbul than its neighboring suburbs. This greenery was the inspiration for the suburb’s new name under the Republic of Turkey. The name Yeşilköy, literally green village, was coined by Turkish poet Halid Ziya Uşaklığil in 1924. Uşakliğil was a resident of the suburb. He gave a new toponym that would not only stress San Stefano’s comforting environment, but one that could also efface the link to local Christian communities. The Turkish name “Yeşilköy” proclaimed instead a brand new identity that could break with the multilingual geography of the Ottoman empire.

The strong presence of Christian communities in Ottoman San Stefano is embodied by a certain number of churches, graveyards and schools. An imposing Catholic church stands out above all other buildings in the centre of town. It catered historically to the “Latin” community, referring to Eastern Mediterranean Catholics who settled in the Ottoman realm over the centuries.

On the other side of town, a small path leads to the “Italian graveyard”, I discover names I was familiar with from research in archives, Italian, French or German-sounding names that recall the plurality within this community: Perpignani, Crespin, Deck etc… The cemetry’s old chapel is about to crumble, the guard tells me visitors are very rare, most families are overseas.

Right beside us however, a bulldozer is flattening the land. The cemetery’s guard mentions the plan to build a new church here. A Catholic church? I ask: “Suryani”, responds a man supervising the bulldozer, referring to the Syriac Catholic community with roots in Eastern Turkey.

Since the Civil War in Syria caused massive migration to Turkey, Catholic Syriacs from Syria seem to favor settling in Yeşilköy where there is an existing Turkish Syriac population. The church will likely cater to both groups together, as Syrian Syriacs have bolstered the size of Turkey’s own community, in decline since the massacres of 1915-18.

This initial ramble through Yeşilköy reveals aggressive European economic intervention dating from the late 19th century that transformed the environment and made San Stefano the bourgeois suburb it is still today. It also showed that Yeşilköy had shrinking non-Muslim communities that were now transforming: where the 19th century Perpignanis left only their tombs, Istanbul’s Syriacs were now building a new religious edifice.

Yeşilköy’s position at the edge of Istanbul on the European side, by the Sea of Marmara, also made it an extremely vulnerable place for the Ottoman Empire’s military defense. San Stefano was occupied twice by foreign military forces in just 30 years (Russians in 1878 and Bulgarians in 1912). San Stefano was the name of an embarrassing treaty the Ottomans had to sign after their defeat to Russia in 1878. The treaty made the Ottomans cede large parts of its possessions in the Balkans such as Romania and Bulgaria.

Russian troops marched through the Balkans before camping their siege close to the Ottoman capital, in San Stefano. It was also there that the army had gathered the corpses of their fallen soldiers. In 1895, in order to bury the soldiers in a more dignified way, the Ottoman Empire accepted to cede some land for a monument commemorating the fallen Russian soldiers.

The construction of an imposing monument started in 1895 and was officially opened in 1898. It is unclear who designed the monument, whereas Turkish sources ambiguously mention “Bozarov” as the head architect, on whom I gained no additional information, Russian sources mention the monument as one of Vladimir Sulsov’s designs, an architect involved in the Russian Revival movement. On the top of the hill above San Stefano, the monument associated classic Orthodox church domes and an imposing militarist, commemorative style at the base. The church also held the tombs of 5 000 soldiers of the Tsar who died during the war. The building was called “Monument” in French, but “Kilise”, meaning church, in Turkish. The Ottoman state might have authorized the construction of a religious edifice more easily than a military one recalling a massive defeat.

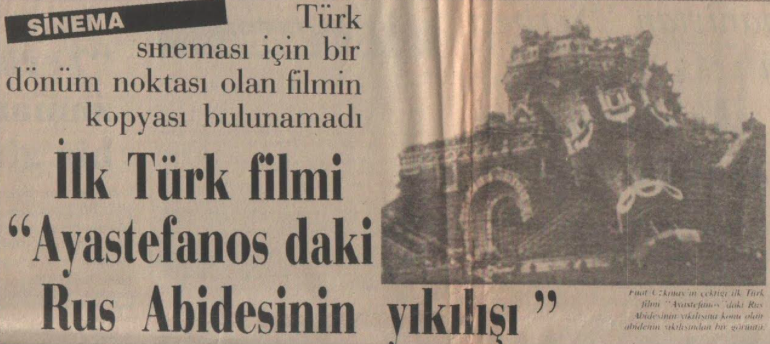

On November 14 1914, at the breakout of the 1st World War, the monument was dynamited under the orders of the Committee of Union and Progress. In a moment of military national union against an embarrassing reminder of previous losses, the Ottoman army organized the destruction as an official commemoration. 26 year-old Fuat Uzkinay, soldier in the Army passionate about cinema, was attributed the role to film the event. Using a camera brought from Vienna by the Sacha-Messter Gesellschaft, the short film would be his first in a long career as a film-maker.

The film supposedly represented the church before, during, and after the demolition. Yet, no copy has ever been found in film archives and some researchers have actually expressed doubts on whether such a film was ever actually made in 1914, or was it only photographs. Today, it is considered the first “Turkish” film: even though films had been done in Ottoman territory, Uzkinay’s would become in the 1940’s Republican narrative the genesis of a national cinema. During the War, Uzkinay headed the “Central Army Cinema Department”, showing how cinema and warfare were associated from the very start in the Ottoman Empire. This could have been inspired by the massive film production that occurred in Italy during the Libyan war of 1911-1912. Italian cinema emerged during the country’s conquest of Ottoman Libya, and perhaps gave Ottomans ideas on how to document their future conflicts.

Demolishing San Stefanos’ Russian monument was part of a larger project of the Young Turks’, that of restoring territorial sovereignty. In order to mark a clear break with previous administrations, the Young Turks, and especially the Committee of Union and Progress that took power in 1913, sought to limit material signs of foreign presence in the capital, and instead assert national sovereignty as a defining principle of the state they wished to build.

This implied containing the right to extra-territoriality provided by the Capitulations treaty. The Capitulations were initially agreements between the Ottoman Empire and an allied state, providing the latter low custom taxes. In the 19th century, it became the core of the legal apparatus guaranteeing European economic, military and cultural interests in the Ottoman territory.

The Capitulations gave foreign powers such as Russia the right to complete sovereignty over different land parcels not only for their embassies, but for various religious buildings too. In fact, the vast majority of buildings enjoying extraterritorial rights in Istanbul were either churches, schools or charitable institutions. From 1913, the C.U.P. attempted to oppose the construction of foreign schools in Istanbul and, in 1914 by declaring war on the Triple Entente, abolished all Capitulations agreements with enemy states.

When I decided to find where the Russian church/memorial used to be, I was mostly curious of how officials could commemorate such a turbulent past. I knew the area had been used by the army as barracks. These military barracks, probably built during World War 1, were still standing, but it was the massive concrete slab right in the center that caught my initial attention. That would be where the dynamite took off, where there once was a monumental Russian church with 5000 buried russian soldiers. Around the whole area were displaced and broken furniture, cracked walls and little hills of garbage or animal bones. No sign of commemoration whatsoever.

This place was conveying a sentiment of exception; it had nothing to do whatsoever with its modern suburban surroundings. The wired fences, although easily cut through, separated two worlds that did not interact. We went to chat with the guard of a luxurious private residence right beside the fence, he had no idea what had occurred in this vacant terrain. Once this fence passed, it seemed various individuals that were generally rejected had found a temporary haven. It was as if no commemoration was necessary, because time would never erase the initial borders between the Russian monument and the surrounding “national” territory. As if the demolition and its representation in a film had had no real effect. The scars were too deep, this place was condemned to its exceptionality.

In 2015, some Turkish journalists discussed a new diplomatic agreement between Russia and Turkey on rebuilding the memorial at the same place. Pointed to as a treason by some newspapers or evoked more favorably by others, this agreement has still not led to any result.

Exploring Yeşilköy invites us to include Turkey and other post-Ottoman countries in Ann Laura Stoler’s call for an investigation of “the uneven temporal sedimentations in which imperial formations leave their marks”. Although mostly interested in areas that have gone through colonialism, the anthropologist’s invitation could well be accepted for other regions also. Yeşilköy’s generally absent monument, and the concrete slab, half-destroyed walls and beer bottles that are left of it today, show what confronting sovereignties can do to a territory. There is definitely the mark here of competing Empires and competing sovereignties: only a wired fence has replaced the historical extraterritorial border.

The 1914 destruction of the Russian church was an early sign of what would happen in the passage from Empire to Nation-State after the First World War in Turkey. Under the Ottomans, the Imperial vision of sovereignty could allow the emergence of spaces that enjoyed a certain autonomy from State intervention. In addition to European abuse of the Capitulations agreement, a suburb such as San Stefano became part of a set of autonomous areas, an exaggerated version of the overall plural environment that existed around the Empire. The Russian monument must have seemed at the time not only provocative, but also out of context in the quiet hills of Yeşilköy.

The story of Turkey as a Nation-State has been one of forced inclusion or abandonment of spaces that had previously enjoyed autonomy, spaces evoking religious minorities, abusive European imperialism or embarrassing military losses. In this attempt to impose territorial uniformity, the choice of which places to remember, and which ones to forget, plays a central part. Yeşilköy’s disappeared monument illustrates how the confrontation of sovereignties may leave indelible scars in contemporary cities, scars that are worth studying.

Despite having lost its main attraction over a century ago, it was this particular concrete slab, or rather the scars around it, that seemed to best illustrate Turkey’s uneasy passage from the plural environment of an Empire to one of a Nation-State.

Special thanks to Oğuzcan Özyurt, who was instrumental in uncovering the location of the abandoned military barracks.

Bibliography:

Bareilles, Bertrand, Constantinople et ses cités franques et levantines, Paris, Bossard, 1918.

Christensen, Peter, Germany and the Ottoman Railway: Art, Empire and Infrastructure, New Haven, Yale University Press, 2017.

Kasap Ortaklan, Oya, “Kolonyalizm Seyretmek: Trablusgarp Savaşı (1911-1912)”, Toplumsal Tarihi, January 2019, n°301, pp. 74-81.

Kaya Mutlu, Dilek, “The Russian Monument at Ayastefanos (San Stefano): Between Defeat and Revenge, Remembering and Forgetting”, Middle Eastern Studies, Vol. 43, No. 1, Jan. 2007, pp. 75-86.

Stoler, Ann Laura, « ‘The Rot Remains’: From Ruins to Ruination », in Ann Laura Stoler (ed.), Imperial Debris. On Ruins and ruination, Durham, Duke University Press, 2013.

Thobie, Jacques, L’administration générale des phares de l’Empire ottoman et la société Collas et Michel, Paris, L’Harmattan, 2004.